|

7/24/2020 Acton's Early Black ResidentsGaining an understanding of a town’s history is complicated by the fact that some residents’ stories are much less accessible than others. Standard town histories from the nineteenth and early twentieth century tended to focus on a small group of socially prominent citizens. People of color were seldom mentioned. Anyone trying to learn about the early Black residents of Acton has had very little material to work with. Records are sparse, and there are sometimes conflicts among the pieces of information that we do have. To better understand early Acton’s racial diversity, we set out to find all mentions of Black and mixed-race residents (slave or free) in Acton’s early records. To do that, we used eighteenth- and nineteenth-century documents that sometimes refer to racial diversity with terms that we would not use today. When quoted here, it is only to give accurate historical evidence about a person’s racial background. There is much work left to do, but in collaboration with the Robbins House in Concord, we offer what we have learned so far. We will start in 1735 when Acton was set off as a town from Concord. We are hampered by lack of census records in the early days but will continue to look for more information. We do have a definitive record that slavery existed in Acton after it became a town. The 1754 Massachusetts slave census completed by the Selectmen stated that there was “but one male Negro slave Sixteen years old in Acton and No females.” (The inventory asked for the number of slaves over the age of sixteen; the wording presumably meant that the male mentioned was in that category, rather than being exactly sixteen years old.) We have no way of knowing if there were any younger slaves. Unfortunately, the inventory did not list either the name of the slave or the slave owner. As a result, we have no idea whether he was eventually freed and whether he stayed in town or moved on to another location. Acton apparently also had free Black and/or mixed-race residents during its earliest years. We are still trying to document their stories. In South Acton by 1731, there was a William Cutting who, according to a story in a published journal of Rev. William Bentley, (volume 2, page 148) was himself or descended from a “Mulatto” slave who “upon the death of his master, accepted some wild land, which he cultivated & upon which his descendants live in independence.” (This story is still being researched; our various efforts to confirm those details have not yet been successful. A 1731 deed from Elnathan Jones to William Cutting is extremely hard to read, but it mentions a purchase price paid to a living person, rather than a gift or inheritance. Another 1732 deed from Elnathan Jones also seems to be a straight sale. Probate records have not yielded clues, either. A possibility is that the story was about an earlier ancestor in a location other than Acton.) An Acton’s Selectmen’s report dated Feb. 2, 1753 mentions a road being laid out, with one of the boundaries being “a Grey oke on Ceser Freemans Land.” Both Cesar and Freeman were names associated with free African Americans of the period. Cesar Freeman’s story is unknown at this point, so we do not know if other Freemans in town records are his relatives. Harvard University has put online a transcribed and indexed version of the Massachusetts Tax Inventory of 1771. This inventory reported the number of each taxpayer’s “servants for life.” According to that database, there were two “servants for life” in Acton, assessed to Amos Prescott and Simon Tuttle. (For relevant entries click here.) We know nothing about the person assessed to Prescott. However, it appears that Simon Tuttle’s “man” fought in the Revolution. At town meeting on March 4, 1783, the town voted to reimburse Mr. Simon Tuttle for “the Bounty for his negro man which was Twenty four Pounds in March 1777 to be Paid by the Scale of Depreciation.” Simon Tuttle was one of the Acton leaders who was charged with recruiting men to enlist from Acton, and it was common practice for the recruiters to pay bounties for enlistment out of their own pockets on the understanding that they would be reimbursed. (Acton took such a long time about actually paying the men back that the value of currency completely changed and adjustments needed to be made “by the Scale of Depreciation.”) The unique thing about this 1783 entry in town records is that the recruit was described at all, in particular his race and the fact that he was considered Simon Tuttle’s man. We have a clue as to his name; Rev. Woodbury's list of known Revolutionary War soldiers from Acton (compiled in the mid-1800s) included the entry "Titus Hayward, colored man, hired by Simon Tuttle." For more information about this soldier, see our blog post about our research into his identity. Acton did have a free Black population in the years of and following the Revolution. John Oliver, listed in later census records (inconsistently) as a free person of color, enlisted for Revolutionary war service from Acton as early as April 1775. John Oliver lived in North Acton in an area near the town’s borders with Westford and Littleton. We are investigating whether there was a community of Black and mixed-race residents in that area. What we know about John’s life in particular was discussed in a previous blog post, and the location of his farm was discussed in another. Another Black Revolutionary War soldier with Acton ties was Caesar Thomson who appeared in Acton’s records after the war. According to an article published by the Historical, Natural History and Library Society of South Natick in 1884 (page 100), Cesar Thompson was a slave of Samuel Welles, Jr., a Boston merchant and the largest landowner in Natick by the time of the Revolution. When Natick needed men to fill its quota of soldiers, Mr. Welles sent Cesar, whose Revolutionary War service was extensive. (See Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, Volume 15, pages 631 and 668). After serving for several years, he was “disabled by a rupture” and was actually granted a pension in January 1783. (Pensions were granted to disabled soldiers, though full pension coverage for veterans was far in the future. Unfortunately, the earliest Revolutionary War pension records were lost in a fire.) As stated in the 1884 article, Natick town records contain the following notation: “Boston, Feb. 18, 1783. This may certify, to all whom it may concern, that I this day, fully and freely give to Caesar Thompson his freedom. Witness my hand, Samuel Welles. A true copy. Attest, Abijah Stratton, Town Clerk.” After the war, free man Cesar Thompson lived in Acton. At the April 5, 1783 town meeting, a committee was appointed to figure out seating for the meeting house (a regular occurrence). Seating arrangements were to take into consideration age and property, using the prior two years’ tax valuations. It was voted that the committee was to “Seat the negros in the hind Seats in the Side gallery.” Clearly, despite years of fighting for political freedom and equality of “all people,” Acton was not ready to grant equality to all of its own people. (It should be noted that it was an era in which citizens paid for pews in the meetinghouse, which was not only a church, but the place were town meetings took place. Presumably, pew placement denoted social status.) In an 1835 centennial speech, Josiah Adams recounted a childhood memory that reveals how it must have felt to be one of very few people of color in the town at the time. Young Adams would watch as Quartus Hosmer climbed the stairs to the “hind seat” of the gallery, eagerly waiting for him to reappear with his queue of “graceful curls” held back by an eel-skin ribbon. (Adams, Josiah. An address delivered at Acton, July 21, 1835: being the first centennial anniversary of the organization of the town, Boston: Printed by J. T. Buckingham, 1835, page 6)

It cannot have been comfortable to be a curiosity to young Actonians and to deal with attitudes made obvious by the meeting house seating vote. Nevertheless, some residents of African descent stayed in Acton. John Oliver farmed and raised his family with his wife Abigail Richardson. (Their known children were Abijah, Joel, Fatima and Abigail. We suspect, but have not yet been able to confirm, that there were others.) Cesar Tomson/Thompson was mentioned in town records when, on January 27, 1785, he married Azubah Hendrick (both were of Acton), Azubah was admitted to the church, and their children were baptized (Joseph, Moses and Dorcas). There is no record of what happened to Azubah, but Caesar married Peggy Green in Acton on December 1, 1785. He also appeared in town records on Feb. 23, 1789 when his tax rate was abated. While researching the Thompson family, we discovered that other Massachusetts towns’ vital records might hold clues about Acton’s Black residents. In Natick, we found two birth records (on the page before the 1801 intention of marriage for Dorcas Tomson, then living in that town): “Moses Hendrick son of Benjamin and Zibiah Hendrick was Born in Acton September 15. 1780 Dorcas Tomson Daughter of Ceasar and Zibiah Tomson was born in Acton April 1. 1784” In Grafton, we found a marriage intention between Polly Johns and “Moses Hendrick, ‘a native he says of Acton but now resident of Grafton,’ int[ention] Aug. 30, 1817. Colored.” Until we found these two records, we had no idea that a Black man named Moses Hendrick had been born in town. Another discovery was that at town meeting in August 1786, the town discussed suing Peter Oliver and Philip Boston “for Refusing to maintain Lucy W___ [name extremely uncertain, some think Willard] Child agreeable to their obligation.” Though both names were associated with free people of color in nearby towns, we have not figured out exactly who these men were or what their connection was to Lucy Willard. On March 19, 1792, the town paid Simon Tuttle Jr. for assistance given to Peter Oliver. The first full census of the United States came in 1790. Though only the heads of household were named, it gives us a more complete picture of the composition of the households in Acton. The census asked for the numbers of free white males (16 or older and under 16), free white females, slaves, and “all other free persons.” Acton had no slaves in this or later censuses. The census taker seems to have had some issues with accounting for “other free persons,” and the census scan is in places hard to read, but from what we can see, the following households had free persons of color:

The census shows six total free persons of color out of the 853 people in 1790 Acton. The seven people in John Oliver’s household were classified as white (2 males, 5 females), as were the nine members of William Cutting Jr.’s household (3 males, 6 females). In the beginning of the 1790s, Acton worked to specify those who were not considered legal residents, a step toward defining its responsibility toward the poor. The Revolutionary War had caused economic distress for many people in the new country. There were no safety nets as we understand them today. Then as now, towns were reluctant to tax people for any expenses that could be avoided. Under the system that had been in place since the early days of the colony, towns could avoid responsibility for supporting poor people if they were not considered legal residents of the town. Formally, this meant giving people notice that they had not been granted permission to live in town and that they should leave (and therefore that they had no right to expect help from the town if they stayed). This process was called “warning out.” From about 1767 to 1789, warning out seemed to be dying out in Massachusetts. However, a law change in 1789 led to a flurry of warnings out in Acton and elsewhere. In the 1790-1791 period, town records show that 23 households were warned out of Acton. Included were a number of Revolutionary War veterans and long-time inhabitants. John Oliver and Cesar Thomson, their wives, and their children were on the list. Both families stayed in town, as most warned-out people probably did in the 1790s. As a practical matter, if those people become indigent, assistance would still have been given them, but the town, relieved of its legal responsibility, could petition the state for reimbursement. Available in Harvard’s Anitslavery Petitions Massachusetts Dataverse is a July 1, 1796 petition from Jonas Brooks to the Commonwealth to reimburse the inhabitants of Acton for “considerable expense in supporting Caesar Thompson a negro man, together with his wife, three small children” who were “not legally settled in said Town of Acton or in any other town in said Commonwealth that your petitioner can find - That he served as a soldier in the Continental army during the last war...” The town sent a follow-up petition for state reimbursement in 1797. As a former slave, Cesar apparently had no legal claim on Natick (despite filling its quota in the Revolutionary War) or Boston, where he might have lived before serving in the military. After the petitions, we found no more records for Caesar Thompson; whether he died in Acton or moved, we were not able to determine. We do know that his daughter had moved to Natick by 1801. The 1800 census asked for more information than its predecessor. Only the heads of Acton households were listed, but the ages of white inhabitants were broken out more carefully. Acton’s census return had a column for the number of slaves and one for “All other persons except Indians not taxed.” With entries in that somewhat perplexingly-named column were the households of:

William Cutting Jr.’s household of seven was again listed as white. Also of note in the 1800 census is that many of the warned-out families were still in town. Acton’s vital records show that in December 1802, Sally Oliver married Jacob Freeman. Their relationship to people of the same surnames in town is unclear (so far). Sadly, Sally and Jacob had only a short marriage marked by tragedy. Their son died on Sept. 3, 1803. Jacob died on July 9, 1804 at age 45. Acton’s death record specifies his race as negro. (In early 1805, Amos Noyes, Joseph Brabrook, and Edward Weatherbee were paid for goods delivered to Jacob, presumably during his sickness.) 1810’s Acton census had a column for “All free other persons, except Indians, not taxed.” Acton households with someone in that category were:

John Oliver’s sons’ 1810 households were classified as white. The household of Abijah Oliver had 1 male 45+, 3 females <10 and 1 female 16-25. Joel Oliver’s household had 1 male <10, 1 male 26-44, 2 females 10-15, and 1 female 26-44. William Cutting Jr. was also classified as white. During the 1810s, town records show payments for some Black residents in need. Between 1813 and 1815, John Oliver was providing help to others, including Abijah Oliver and, when sick, “Abigal” Oliver and Sally (Oliver) Freeman. In 1811-15, John Robbins and David Barnard were reimbursed for boarding “Titus Anthony.” Later records give clues that he may have been Black (see below). (Probably relatedly, in March 1810, town meeting records mention a lawsuit by the town of Townsend against Acton “for supporting Hittey Anthony and Child.”) Acton town meeting took up Titus Anthony’s case in September 1811; unfortunately, the discussion was not reported in the extant records. In 1813, David Barnard was paid for providing for the poor and, separately, for “2 payment for the Negro” (name unspecified). 1820’s census yields more information about Black town residents. In that year’s report, “Free colored Persons” had four columns each for males and females of differing ages. Households with entries in those columns were:

1820’s total “free colored” population was listed as 17, which does not match the numbers given in the columns, so the accounting is uncertain. John Oliver’s 2-person household was listed as white. Regardless of the counting issues, there was obviously quite a community of people of color in Acton during the 1820s. Most lived in the North and East parts of town. The households of Jonathan Davis and Uriah Foster would have been near today’s Route 27 in North Acton. John Oliver’s sons Abijah and Joel eventually moved closer to East Acton; land records indicate that their father helped with financing. In 1830, federal census takers were given forms two page-widths across that specified ages and sex of both slaves and free people of color and had a “total” column for each family that should have encouraged accurate record-taking. The only household in which free persons of color were enumerated was John Oliver’s:

John’s son Joel Oliver was listed as white, living with 5 white females. Simon Hosmer’s family no longer was listed with a free person of color. This jibes with the hypothesis that the “Quartus Hosmer” mentioned by Josiah Adams lived in the Jonathan/Simon Hosmer household. In Acton’s vital records, the handwritten register of Acton deaths for 1827 shows: “June 30 Quartus a Blackman 61” The Hosmer name was not given in the death record. (This entry was indexed on Ancestry.com as “Quartus Blackman,” but that is clearly an error.) In Acton’s transcribed and published Vital Records to 1850, the listing appeared under “Negroes, Etc.” That entry adds information from church records (“C. R. I.”): “Quartus, ‘a Black man,’ June 30, 1827, a. 61 [State pauper, a. 64, C. R. I.] A state pauper meant that the individual had no “settlement” status. (Acton could not send him or her back to another Massachusetts town for financial support, but he/she was not officially accepted as having a claim on Acton either.) By this time, if a person with no official claim on a town was in need based on age, disability, illness or poverty, he/she became, officially, a state pauper, and expenses incurred by the town would be billed to the state. Apparently, former slaves often found themselves in this position (Cesar Thompson, for example), as well as new immigrants from overseas and anyone not connected to a town by family or marriage. Quartus’ status as a state pauper means either that he was free but didn’t start off in Acton or that he had started out a slave. If we are correct that the free person of color in the Hosmer household was this Quartus, he clearly had a long relationship with the family. The available records do not give us much information about what the relationship was, but we have not found evidence that he had been enslaved by Acton Hosmers. This Quartus was too young to have been the over-16-year-old slave in the 1754 census, though slaves younger than sixteen were not reported. The 1771 tax valuation showed no Acton Hosmers with “servants for life.” He could have been freed by then or could have been enslaved elsewhere in his early years and later entered the Hosmer household as a free working person. The 1840 census showed “free colored persons” in the households of:

The census shows the household of John Oliver, especially noted for being 92 years of age and a military pensioner, as white (1 male under 5, 1 male 5-9, 1 male 90-99, 1 female 5-9, 1 female 40-49). His son Joel Oliver’s household is also listed as white, (2 males, 30-39 and 60-69, and 2 females, 15-19 and 50-59). During the 1840s, many in Acton were advocating for an end to slavery in general and for improvements in laws affecting the lives of Massachusetts’ Black residents. A digitized 1842 petition from Acton to allow white people legally to intermarry with other races was signed by 70 women, including Abigail Chaffin who was most likely Abigail Richardson (Oliver) Chaffin, herself of mixed-race ancestry. (Abijah Oliver’s daughter, she had married Nathan Chaffin, born in Acton to Nathan and Mary Chaffin. After that point, records always seem to have classified her as white.) Abigail Chaffin also signed two other anti-slavery petitions in 1842 ( Petition against admission of Florida as Slave State and Petition to abolish slavery in Washington, DC and territories and to end the slave trade). Abigail Chaffin was remembered in a Chaffin family history (pages 269-270) as “one of the most remarkable women ever born in Acton, on account of the wonderful sagacity, industry and executive ability, which characterized her through the whole of her life and... together with mental and physical vigor, to a very rare age. ... Even after she was four score and ten she was able to do more for others than she needed to have done for herself.” After the death of her husband in 1878, she moved in with her son Nathan who prospered in the restaurant business in Boston. She lived in Arlington for many years, and she died in Bedford in 1911, after having “passed her last years not only in the possession of the comforts, but of the luxuries of life.” Back in Acton, the 1850 census, for the first time, listed the names of all residents of the town. A column for race showed the following residents of color:

The race column for all other residents was left blank (including the 7-person household of Joel Oliver, Abijah’s brother). The 1850 real estate valuation for the town shows Ephraim Oliver (son of Joel) with buildings valued $375, plus 40 acres of improved land and 20 acres of unimproved land; he was living with Joel at the time. Abijah Oliver had been farming in East Acton, but obviously he was no longer able to care for himself. It was not particularly unusual for the aged, regardless of race, to need assistance. Massachusetts took its own census in 1855. We have noticed in the past that the Acton census taker that year was particularly careful in recording full names, and the census taker noted more information about race as well:

We have not yet been able to find out where Titus Anthony Williams came from and how he ended up in Acton’s poor house. The middle name reported in the 1855 census raises the question of whether the “Titus Anthony” who was receiving assistance in the 1810s was actually the same Titus Anthony Williams who spent many years in Acton’s poor house (occupation farmer). If so, he would have been a young child when he first appeared in Acton’s records. By the mid-1800s, Acton was changing. The arrival of the railroad brought new industry and new people to town, and events in Europe brought new immigrants who would have competed for jobs and land. Most descendants of Acton’s early Black residents eventually left Acton to find opportunities elsewhere. Occasionally, they were mentioned in later records. Sickness, disability, loss of a breadwinner, or extreme old age could change economic status. Acton’s town report of 1855-1856 shows payment to the city of Boston for the support of Elizabeth Oliver (probably the recent widow of Abijah Oliver), and to the town of Concord for the burial of two of Peter Robbin’s family, as well as to Daniel Wetherbee of Acton for goods provided to that family. (Peter Robbins had recently died. He was divorced from John Oliver’s daughter Fatima by that time; apparently, his common law wife Almira/Elmira came from Acton, though her parentage is currently unclear. She is referred to in Acton’s records as Elmira Oliver.) The 1857-58 report shows money paid to Lowell for the support of Sarah Jane (Tucker) Oliver. (She apparently married William P. Oliver and then Asa Oliver; their connections to other Acton Olivers are still being worked out). Others receiving help that year who were not living at the poor farm included Sarah Spaulding (John Oliver’s widowed granddaughter) and Elizabeth Oliver. The 1860 Federal Census showed the following:

The 1860 census also surveyed the town’s agriculture and gave details about Ephraim Oliver’s farming operation, located at approximately 283 Great Road in East Acton. Ephraim Oliver owned 43 improved and 10 unimproved acres worth $3,000, plus $100 in farming implements, a horse, four milking cows, and fifteen other cattle. His farm produced 140 bushels of “Indian corn,” 15 bushels of oats, 40 bushels of “Irish potatoes,” 200 pounds of butter, 10 tons of hay and 5 bushels of grain seed. Though she was not listed in the poor house in the census, Sarah (Olivers) Spaulding was listed in Acton’s 1860 death records as a pauper. She died, widowed, at age 36 on Oct. 14, 1860 and was listed as a quadroon, daughter of Abijah and Rachel (Barber) Oliver. (Abijah was married to Elizabeth Barber, so that is probably simply an error.) The final census in this survey is the Massachusetts census of 1865. By that time, Civil War and emancipation had set enormous changes in motion. The census reported the following people of color in Acton:

All other residents were classified as white, including the five-person household of Ephraim Oliver. We still have many questions that need answers. In the relatively helpful records of the 1860s, we found other mentions of Olivers with connections to Acton that we have not yet been able to untangle:

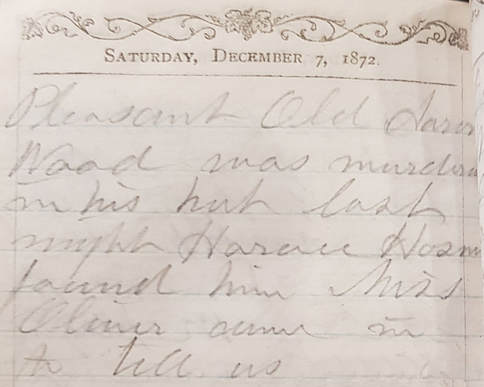

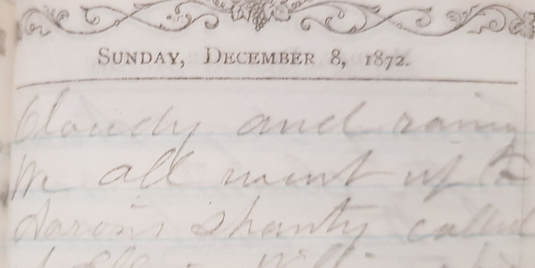

Researching the lives of Acton’s Black residents is an ongoing project. What has become clear from trying to list all people of African descent who lived in Acton from its earliest years to the end of the Civil War is that available records, though far from complete, do allow us to find at least some of them. The town’s vital records and censuses, the backbone of much genealogical research, are only the beginning. Though searching the columns of early censuses for people of color was helpful, we discovered inconsistency in the reporting of race that certainly understated the number of Black and mixed-race residents. Acton’s vital records only reported some of their life events. By tracing descendants, we were able to uncover new details such as Acton births recorded later in other towns. Another source was town meeting and expenditure reports that proved when people were in town and where they might have gone, especially if they provided financial assistance to others or needed it themselves. If you are a descendant of any of Acton’s Black and mixed-race residents, have any additional information about them, can correct any information provided here, and/or know of other people who should be on our list, please contact us. We would appreciate help in bringing their stories to life. 5/25/2020 Remembering Thomas DarbyOne of the little-realized facts about Acton’s Revolutionary War soldiers is that we do not have a complete listing of who they were. Captain Isaac Davis’s company of Minute Men who marched to Concord on April 19, 1775 are quite well-documented, thanks to the testimony of long-lived individuals and the pride of Acton residents that their Minute Men were first at the bridge and suffered losses as a result. A monument in the center of town reminds us of their place in history. However, two other companies of Acton men served that day. We can figure out some of them thanks to a wonderful donation to the Society of Captain Joseph Robbins’ papers, but we still do not know all who participated. The Revolutionary War stretched on for eight years, and while records became somewhat better as the war went on, not all soldiers’ service was perfectly documented. In the years since, because of local focus on those who were killed on the war’s first day, soldiers who served and died later and in places farther away have received much less attention in Acton. One of those casualties was Thomas Darby who was killed at the Battle of White Plains in 1776. In honor of Memorial Day, we attempted to find out something about Thomas Darby. His surname was not a common name in Acton in later years. He is not mentioned on any monument, marker, or historical map. There are no streets bearing his name in a town full of Revolution-themed roads. Given this lack of attention, we assumed that he was a young, unmarried man who probably did not have family around or whose extended family died out early. That assumption turned out to be incorrect. Though we were not able to find out much about his life, we can at least try to give his story some family context. We are, for this blog post, indebted to and somewhat at the mercy of published town histories and genealogies of Thomas’ family. Though we have used online vital, town, military, probate, and land records to try to corroborate and supplement their stories, the records of the time are incomplete. Some research avenues were limited after COVID-19 led to the closure of libraries and archives, but the Darby family is hard to untangle even in the records that do exist. The Darbys were numerous, were sometimes called “Derby,” “Daby” or another name variant, and tended to repeat first names within and across generations. (As one example, a Daby family of Harvard, MA seems to have been intermingled with Thomas’ family in some histories, though the actual connection, if there was one, is uncertain.) As best we can tell, Thomas descended from three generations of men named John Darby. John Darby was certainly a common name in Thomas’ family; it was given to Thomas’ eldest brother and two younger brothers, the last of whom reached adulthood. The first of Thomas’ male ancestors noted in most genealogies was fisherman John Darby of Marblehead. What usually was not mentioned was his notoriety. According to Eric Jay Dolin’s Black Flags, Blue Waters: The Epic History of America's Most Notorious Pirates (among other histories), John Darby was on the crew of a boat boarded by pirates in August 1689 and, quite voluntarily, threw in his lot with the pirate Thomas Pound. John’s new career was short-lived as the pirates’ activities over the next two months led the Massachusetts governor to send out a crew after them. When they caught up with the pirates in Tarpaulin Cove (located on an island near Martha’s Vineyard), John Darby was killed in the ensuing battle. His wife back in Marblehead was left with five young children.[i] The second John Darby (1681-1753), Thomas’ grandfather, married Deborah Conant, presumably before Dec. 27, 1704, and had many children in Essex County, MA. They moved to Concord around 1721. Deborah’s brother Lot Conant also settled in Concord; a deed in 1745 mentioned that a piece of land owned by John Darby was bounded in part by Lot Conant’s land. In that 1745 deed, John Darby sold part of his farm and other lands to his eldest son John (Thomas’ father), carefully giving him the right to cross the barnyard to get to his own barn doors, to cart his hay, and to use the well. Son John was also given one fifth of the apples in the orchard. The elder John’s will, dated 1747, left to his wife “Deborah Darbie” any lands and buildings that he had not yet disposed of in the “southerly part of Concord” and his interest in land in Acton. The will conveniently named his children: John (Thomas’ father), Andrew, Ebenezer, Benjamin, Joseph and Robert Darbie, Deborah Wheeler and Mary Heywood. Thomas’ father John Darby (1704-1762?) married Rebecca Tarbox in Wenham on March 16, 1728. John and Rebecca had two children, John (1729-1732) and Thomas (born 1731). Thomas’ mother died by 1735. His father was remarried to Susanna (possibly Jones), and they had eight more children: John, Rebecca, Lucy, John, Anne, Elizabeth, Nathaniel and Elnathan. As far as we can tell from land records, Thomas grew up in “the westerly part of Concord” near his grandparents and a large number of siblings, uncles, aunts, and cousins. (The 1745 deed from his grandfather to his father confirms that Thomas’ family was living on his grandfather’s farm at the time.) At least some of the family ended up in Acton after it was set off as a separate town in 1735. Thomas’ uncle Andrew Darby was considered one of the founding settlers of Acton (see Phalen, page 28) and was chosen for various responsible roles in its early years, including selectman and assessor. Four of Andrew’s children’s births were reported in Acton vital records. Andrew moved to Worcester County around 1848 and was again a founding father of Narraganset No. 2 (later Westminster), leaving a large number of descendants in that area. Thomas’ uncle Benjamin bought Acton land abutting Iron Work Farm in South Acton in 1844. Joseph Darby bought land and a cooper shop in Acton in 1776. One thing we can say with certainty is that Thomas was not a lone Darby who happened to sign up with Acton’s minute men. Darbys and their relatives had been in Concord and Acton for decades. Unfortunately, however, records actually detailing Thomas’ life are very few. According to Concord vital records, Thomas Darby was born January 12, 1731 to John and Rebekah Darby. His baptism was recorded in the records of Ipswich’s “Hamlet Parish Church” on Jan. 17, 1731. As noted, Thomas grew up in Concord and lived on his grandfather’s farm. According to many sources, Thomas married Lucy Brewer. Presumably they married around 1761, but we have not found a marriage record. We found no land records bearing Thomas’ name, but he was living in Acton by 1757 when, during the French and Indian War, he was listed as a private in Captain Samuel Davis’ “Foot Company,” Acton’s Alarm Company #2. His children with wife Lucy were recorded in Acton’s town records (Vital Records, Volume 1, page 63, all together):

Thomas was mentioned in Acton’s town records on March 26, 1769 when he was paid two pounds for keeping a school. Though hard to read, an order dated April 19, 1770 indicates that Thomas “Derby” was paid one pound, ten shillings for keeping a school the next year as well. That is the only mention of Thomas’ work that we have found. He could have been living and working on a relative’s land but we have found nothing to prove that. The next records we have of Thomas come from Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War. Thomas Darby was listed as part of John Hayward’s company that answered the “Lexington Alarm.” John Hayward was Captain Isaac Davis’ second-in-command and became the leader of Acton’s minute men when Davis was killed. Thomas Darby presumably was drilling with Captain Davis as tensions with the British rose in late 1774 and early 1775. He was one of those who marched to Concord on the first day of the war, was there in the first company facing the British, and must have witnessed the death of Isaac Davis and Abner Hosmer. Apparently, Thomas had the full support of his wife in turning to soldiering. According to a colorful story in the history of Hudson, New Hampshire, Lucy (Brewer) Darby “sheared her sheep, spun the wool, wove the cloth, colored it with butternut bark, made the uniform and carried it to her husband, then in temporary camp, and told him to go fight for his country.” (page 575) Thomas’ war service continued. Records for early war service are spotty, but a pay abstract for a travel allowance dated Winter Hill, Jan. 15, 1776 confirms that he was part of Washington’s army participating in the siege of Boston that winter. He was serving as Corporal in Capt. David Wheeler’s company, Col. Nixon’s regiment. Joseph Darby of Acton was also in the company, probably the son of Thomas’ uncle Joseph who still lived in Concord. Thomas and Joseph (“Derby”) were both in Capt. Simon Hunt’s company that was called out to help fortify Dorchester Heights in March 1776. Thomas seems to have been reported as a private for that service. In Sept. 1776, a company was formed of men from Concord, Acton, Lexington, and Lincoln to serve in the Massachusetts Third Regiment under Eleazer Brooks. Simon Hunt of Acton was captain. A list of Simon Hunt’s company (that did not include a year) showed Thomas Darby as a corporal. Fifteen Acton men were in the company, including Thomas Darby of Acton and Nathan Darby of Acton/Concord, both of whom reported at White Plains. Nathan may have been another son of Thomas’ uncle Joseph, but it also could have been Thomas’ brother Nathaniel whose later service (clearly as “Nathaniel Darby” from Acton) was credited to “Nathan” in the Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors compendium. Either way, Thomas had family in the company.[ii] Though we know that Thomas served and died at White Plains, even the role of his company there is hard to pin down, as later reports on the battle were somewhat conflicting. Fletcher and Shattuck’s histories (of Acton and Concord, respectively) both made sure to assure us that Colonel Eleazer Brooks’ regiment behaved bravely. Whatever happened in the chaos of the battle, the result was tragedy for Thomas’ family; Lucy was left a widow with four daughters to support. Thomas does not show up in probate or land records; presumably he left little money behind. There is no indication in town records that Acton helped Thomas’ family financially. We can only assume that they took refuge with relatives elsewhere, probably in Ashby, MA. A Massachusetts Society of the Sons of the American Revolution publication stated that Lucy was a pensioner. (page 237) Though it would seem that widow Lucy Darby should have received a pension under a 1780 Act of Congress, we have found no evidence of that seemingly simple fact in online records. (Perhaps the 1800 fire that consumed the earliest pension records destroyed her application, but we found no records of payment, either.) We finally found additional records of Thomas’ family when his daughters started to marry. On May 28, 1788, daughter Rebeckah married Revolutionary War veteran John Pratt in Harvard, MA. Both Rebecca and John were recorded as residents of Harvard at the time, but John had apparently moved to Fitchburg, MA where the couple settled and raised their nine children, one of whom was named Thomas Darby Pratt. On November 27, 1788, Thomas’ eldest daughter Lucy married John Gilson who enlisted from Pepperell, MA at the age of fourteen and was in the Battle of White Plains. A Samuel Gilson of Pepperell was in the same company and was reported killed at White Plains; this may have been his father. (Sources disagree.) The marriage between Lucy and John Gilson was recorded in Townsend and Ashby, MA, both giving Lucy’s residence as Ashby. A profile of the Gilson family in Hayward’s history of Hancock, NH tells us that John Gilson was a blacksmith. He and Lucy settled originally in what is now Hudson, NH and then moved to Hancock, NH. (They may have lived for a time in Bennington as well.) They had eight children, one of whom was named Thomas Derby Gilson. (We checked other sources to confirm his middle name. Aside from the mention in the Hancock history, we only found him listed as Thomas D. Gilson in other records.) Both Thomas Darby’s daughter Lucy Gilson and Thomas’ widow Lucy Darby died on August 10, 1834 and were buried together in the Hancock cemetery. Thomas’ widow had lived with John and Lucy Gilson and their family for nearly fifty years. Widow Lucy Darby had managed to accumulate some money and left a will, written in 1832, that named her daughters and six of her Gilson grandchildren. Thomas’ daughter Phebe married Jonathan Rolfe on August 30, 1792. Both were of Ashby, MA, but their marriage, like Lucy’s, was recorded both in Townsend and Ashby. Apparently, Jonathan was a carpenter. Two histories gave Jonathan the title of “Captain,” but we were unable to find out why. Jonathan and Phebe stayed in Ashby until after 1810, and their nine children seem to have been born there. Jonathan and Phebe later moved to Dalton, NH. Jonathan died in 1825 and Phebe in 1840, and they were buried in Dalton. Youngest daughter Mary (also known as Molly or Polly) married Deacon Moses Greeley (1764-1848) who was born in Haverhill, MA. His father also served in the Revolutionary War. Moses first married a cousin Hannah with whom he had two daughters. After she died in in 1793, Moses and Mary married and lived in Nottingham West (later Hudson), New Hampshire. Moses was a blacksmith and apparently a successful farmer. The couple had nine (or possibly ten) children, one of whom, Moses, Jr., legally changed his name in 1829 to Moses Thomas Derby Greeley. Their eldest, Reuben, like his father, served as a selectman, becoming chairman of the Board, town clerk, and representative in the Legislature. One of Mary’s grandchildren was the locally well-known Moses Greeley Parker. Mary Darby’s husband Moses Greeley died in 1848, and Mary died in 1856. They were buried in Hudson, NH. A history of Hudson, NH has personal sketches of Moses (including Mary) and Reuben and includes pictures of all three of them. Even though Thomas Darby was one of Acton’s celebrated Minute Men, his service has been given surprisingly little attention. Perhaps because he survived April 19, 1775, Acton’s historical attention focused instead on those who were killed that day. Contrary to our expectations, he came from a large family and left many descendants. None of Thomas’ daughters settled in Acton; stories about his life would have been passed down elsewhere. If anyone has more to tell us about Thomas Darby, his family, and or any other Acton Darby connections, we would like to document their history. We would also be grateful for any corrections or additions to this story. Please contact us. Endnotes: [i] We would like to find more records to make sure of the connection between John the pirate and Thomas’ great-grandfather. The name Darby was much less numerous than in later generations, so duplicate John Darbys are much less likely, but we did want to confirm the identity. The pirate John was known to the remaining members of his fishing vessel, so his identity was no mystery at the time, and there were witnesses to his activities as part of the pirate crew. For us, genealogies tell us that Thomas’ great-grandfather was a fisherman, and that he came from Marblehead. Many sources say that the pirate was from Marblehead working on a boat out of Salem and that the pirate’s widow was left with four or five children. The timing of pirate John’s death in October 1889 is consistent with (1) Thomas’ ancestor’s probate inventory dated Janr 17, 1690 (given the writing, it might be June 17), and (2) his widow Alice Darby, mother of five, marrying John Woodbery on July 2, 1690. [ii] To complicate matters further, Thomas also had another first cousin named Nathan who was in Westminster by that point as well as a brother named Elnathan. Various cousins of Thomas served at different times during the Revolution; with name duplication, telling them apart in records becomes complicated and depends heavily on location at enlistment. Checking online scans (via Ancestry.com) of the 1778 roll of the 15th Regiment, listed by town, we found Nathaniel listed as a soldier from Acton in Hunt’s company; at that point, at least, the soldier in Hunt’s company appears to be Thomas’ brother. Elnathan seems to have enlisted for service from the town of Harvard in 1777. Select References Used (in addition to digitized vital and other records):

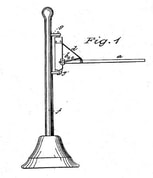

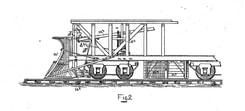

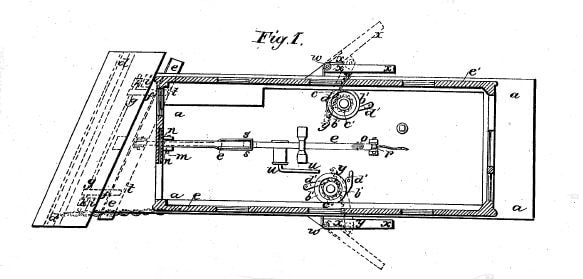

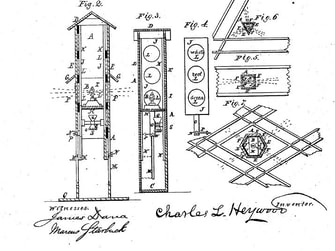

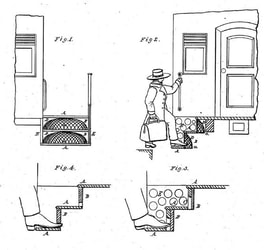

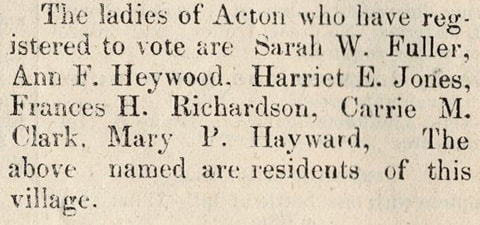

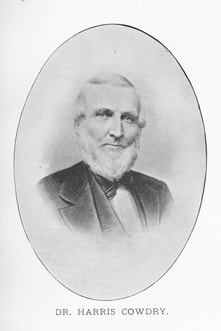

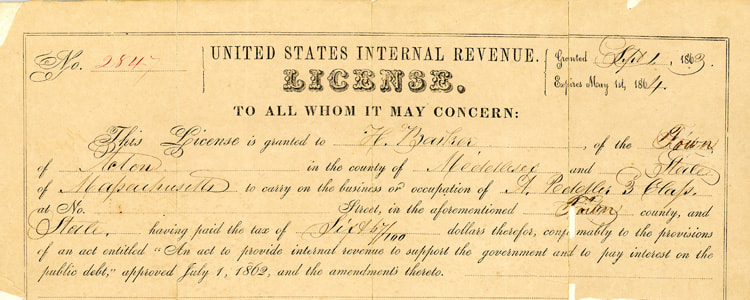

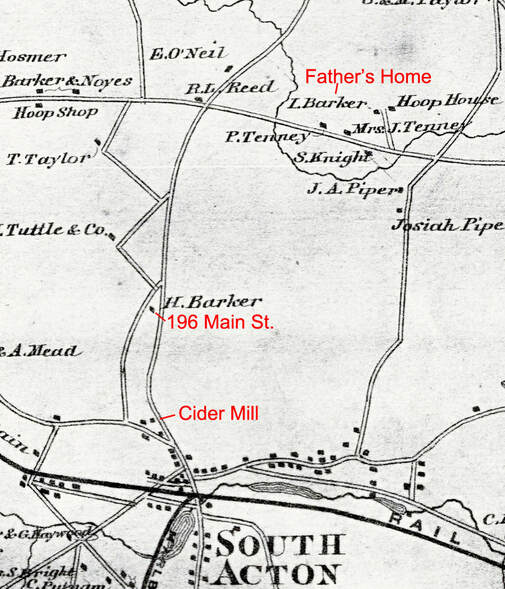

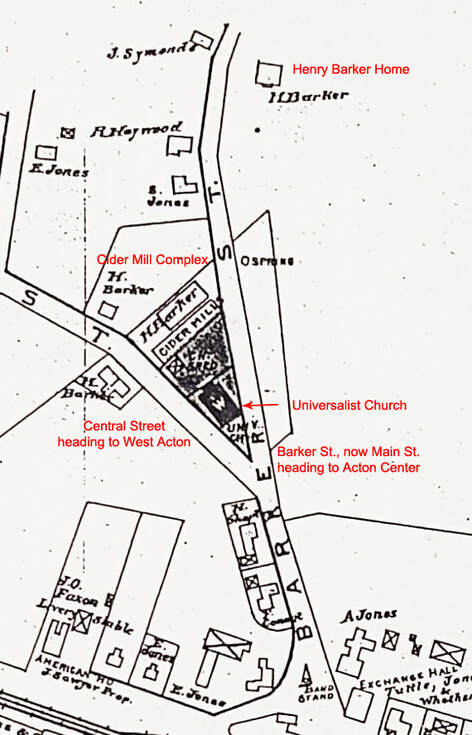

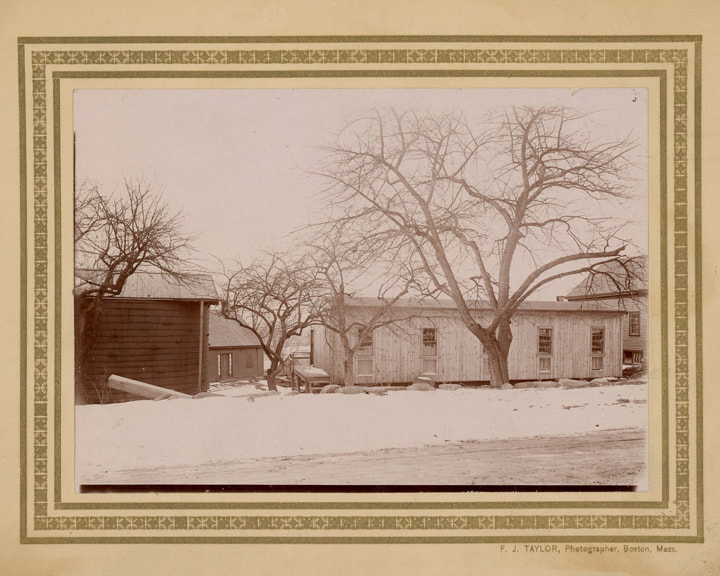

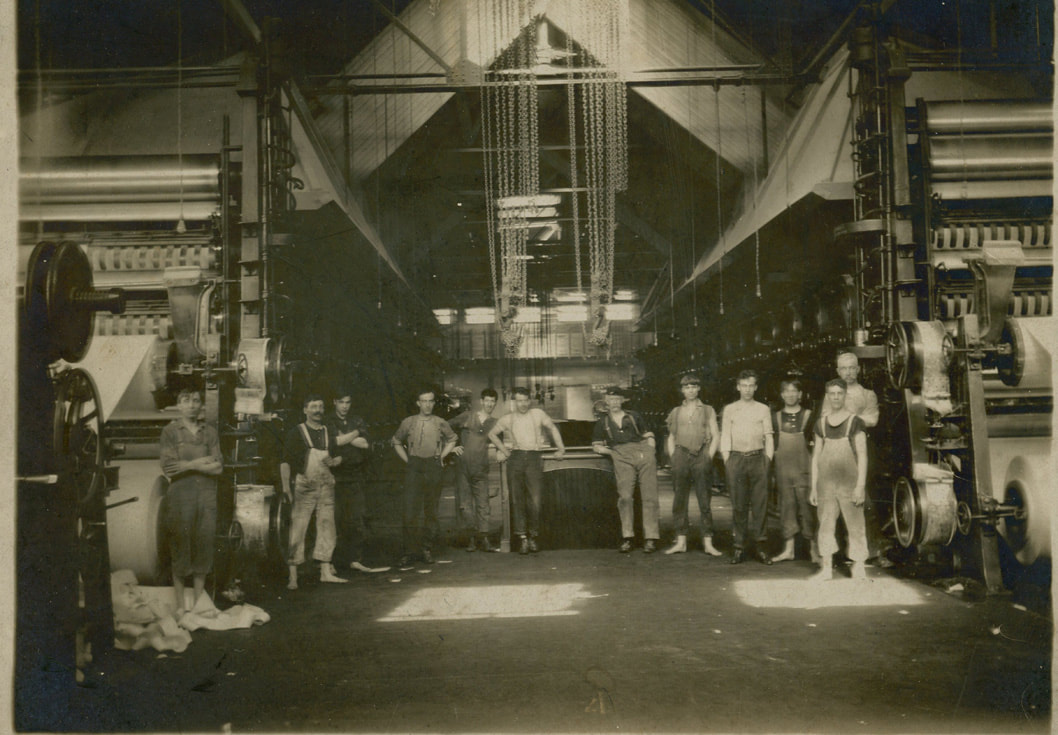

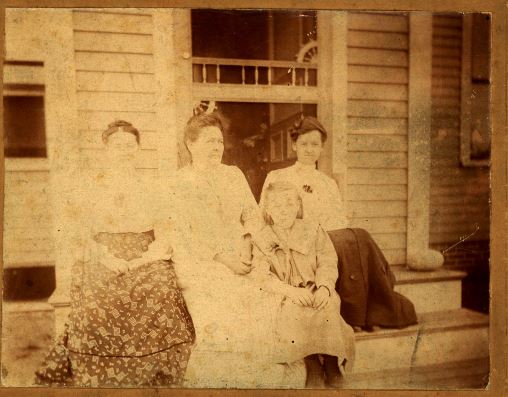

C. L Heywood [43] C. L Heywood [43] Ann F. Heywood, subject of our last blog post on Acton’s first female voters, was married to Charles L. Heywood, owner of a South Acton mill. We had very little information about them to start, but our research revealed that they were celebrities by the standards of South Acton in the 1870s. Charles, as it turns out, was unusual by any standard. Ann evidently was herself worthy of note, but, as is frustratingly typical, she was much less documented in written records. The Early Years We do not know much about Charles and Ann's early lives. Records of that time are sparse, and neither Charles nor Ann grew up in Acton. We do know that Charles Lincoln Heywood was born to Lincoln Heywood and Rebecca Priest in Lunenburg, MA on April 17, 1828. The eighth child in the family, he grew up in Lunenburg and was educated in its local schools. His father was Deacon of the Unitarian Church. About the time that the Fitchburg Railroad came through Lunenburg (approximately 1845), Charles went to work for the line as a crossing tender. Charles was obviously a young man of ability; he moved up steadily in the railroad's ranks. By 1850, 22-year-old Charles was living in Fitchburg with the Israel Goodrich family and working as a Wood Agent for the railroad. In the 1855 Massachusetts census, he still had that title and was living in a "hotel" in Fitchburg. Within the next year or two, Charles was promoted to Roadmaster, a managerial position responsible for track conditions and safe operations. He continued to serve as Wood Agent as well, at least at first. Charles soon moved to Concord, MA, where he joined the Corinthian Lodge of Masons. He was a resident of Concord when he married Ann Tyler. [1] Ann Frances Tyler was born June 18, 1825 in Attleboro, MA, the fourth child of Samuel Tyler and Betsey Samson. Ann was only three when her mother died. According to a Tyler genealogy, her father was "an enterprising, influential man in Attleboro, and a pious church-member. His will mentions him as 'a depraved worm of the dust.'" It appears that Ann and Charles both grew up in homes in which religion was important, but beyond that, we do not know any more about their upbringing or how they managed to meet. They were married on November 25, 1857 either in Attleboro or in Providence, RI where Ann was living at the time. [2] A Busy Life The couple moved at some point to Belmont, MA where Charles was living when he registered for the draft in 1863 and where he became a charter member of the local Masonic lodge. In September 1864, after many years of service, Charles was promoted to the position of Superintendent of the Fitchburg Railroad. He would serve in that role for about fourteen years. [3] Charles seems to have possessed an unusually active mind and the energy to turn his thoughts into reality. Apparently, it was his idea to create the amusement park at Walden Pond in Concord that opened in 1866. Though Charles grew up in Lunenburg, his family roots went way back in Concord. His relatives seem to have owned a significant portion of the shoreline of Walden Pond, and the Fitchburg Railroad conveniently went right by. The railroad bought up land bordering the pond and cleared some of the woods to create an entertainment area with a large hall for use as a dancing pavilion or a gathering place for large meetings. Tables and seats were provided for picnicking, and for the more actively inclined, there were trails, swings, “teeters,” bathhouses for swimmers, and rowboats. People were delivered by train right to the park that was usually called some variant of “Lake Walden” or “Walden Pond Grove.” [4] Though to many today, Walden Pond should be kept as pristine as Thoreau saw it, at the time, many would have considered the park a societal benefit that allowed city dwellers a respite in fresh air and a beautiful spot. It was enormously successful. A Waltham Sentinel reporter, having recently enjoyed “a fine boat ride with several of the Fitchburg railroad officials, accompanied by their ladies; among the party Mr. Heywood, the Superintendent,” wrote that the park was “rapidly becoming quite popular.”[5] J. C. Moulton, “a well known Artist from Fitchburg” was there that day with his “machine” for making stereopticon views for sale, which would have been good to promote the park. The first season of the venture was summed up in the Nov. 30, 1866 Waltham Sentinel; the Fitchburg Railroad had brought out thirty different groups to the grounds, about 10,000 persons, without mishap. [6] The venture grew from there. By June 1869, large boats with side wheels and docks to accommodate them were added. During its first five years, newspapers reported that Walden hosted gatherings of veterans, temperance advocates, Masons, Good Templars, Sunday Schools, Spiritualists, and students and alumni of the New England Conservatory. In July 1869, the "Grand Temperance Celebration" featured speakers, music, dancing, boating, swinging, ball playing and a Velocipede rink. The special excursion admission and train fare from Acton was 50 cents. The third annual Musicians’ Picnic in 1870 drew more than 3,000 people to hear at least seven bands including Acton’s 19-piece band led by G. Wild. On July 4, 1870, the estimated crowds were 8,000-10000; the railroad used every serviceable car to accommodate them. In the early years of the 1870s, trains started bringing “the children of the poor” out from Boston to enjoy a day at the amusement park. [7] Walden was only one of Charles L. Heywood’s brainstorms. As Superintendent of the Fitchburg Railroad, he conceived numerous special excursions to provide people with recreation, edification, or simply a change. In addition to promoting events at Walden and closer to the city, the railroad carried people to West Townsend and environs to gather greenery, trailing arbutus, checkerberries and mosses with which to celebrate May Day. Excursions were arranged for people to see the engineering wonder of the Hoosac Tunnel. Superintendent Heywood invited the famous Rev. Henry Ward Beecher to preach at Lake Pleasant, a Spiritualist campground in Sept. 1875. Montague depot was nearby. [8]  Bridge Guard Bridge Guard Charles’ mind was also busy thinking of ways to make the railroads safer. In 1866-67, he was granted patents for a railroad snow plow and a “bridge guard” to keep brakemen from being knocked off the top of railroad cars as they worked. Charles’ plow, apparently “ingenious,” efficiently and thoroughly cleared the tracks. Adjustable “wings” could clear five feet on either side of the tracks and would retract if they hit an obstacle. His plow was used, at the least, by railroads in Massachusetts, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin. Charles’ “bridge guard” was “a light movable crane” that would give brakemen working on top of railroad cars warning before they were hit by the bridge.[9] It apparently was widely adopted, as it “proved a great protection against accidents.”[10] Charles may have traveled to promote his inventions. In addition to exhibiting at the 1865 Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association in Boston, he was also one of the exhibitors at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia.[11] Charles became known as a strong advocate for railway safety: “Even the ordinary signs at crossings he did not consider sufficient, and the reading on many of them he had so amended as to direct travelers to ‘look both ways’ before attempting to cross the tracks. There was no device brought to his attention that promised to reduce the chances of accidents which he did not forthwith adopt.” [12] Charles and Ann seem to have moved around. They may have stayed in residential hotels at times and may have had multiple properties at others, but they were always near the railroad. In May 1866, Charles bought a house on Main Street, near the corner of Auburn Street, in Charlestown, MA. He and Ann joined Harvard Church there in early 1868, and in May 1869, an ad appeared in the Boston Traveler “For Sale or To Be Let on a Long Lease – A good House, Stable, and 17,000 feet of land, well stocked with fruit and shade trees, near Waverly Station, Belmont, Mass. Inquire of C. L. Heywood, at Fitchburg Railroad, Superintendent’s Office.”[13] Charles transferred his Masonic membership to Charlestown in November, 1871. For some reason, we were not able to find Charles and Ann listed in the 1870 census; perhaps they were traveling at that time or staying at a summer location, possibly in South Acton. As far as we can tell, Ann and Charles had no children of their own. Around 1870, Ann’s niece, Eunice Tyler (Read) Crawford, daughter of Ann’s sister Eunice and wife of George Crawford, passed away. She left a child, Herbert Lincoln Crawford, who had been born in Pawtucket, RI in September 1868. Charles and Ann took him in. Whether or not the arrangement was meant to be temporary, it became permanent, and in 1878, while living in Belmont, the couple adopted the boy. His name was changed to Lincoln Crawford Heywood. Abundant Charity While still working for the railroad, Charles gave of his prodigious energy and his money to charities. He took special interest in the welfare of the inmates of the Charlestown state prison and taught Sunday school there. The Boston Daily Advertiser noted in January 1870 that he had given his students a book of their choice as a Christmas gift. He was also involved in the Massachusetts Society for Aiding Discharged Convicts. His belief in rehabilitation was obviously deeply held, because his kindness to prison inmates extended to the man who had killed Charles’ brother George. According to Cunningham’s History of Lunenburg, Charles met the prisoner responsible for his brother’s death, forgave him, and actually helped to get him pardoned. We were able to confirm the pardon but not Charles’ role in it. Cunningham was well acquainted with Charles’ father and apparently knew Charles, so presumably he heard the story from someone who knew what happened. [14] Prisoners were not the only beneficiaries of Charles’ generosity. Charles served on the Executive Committee and as director of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals for years and took an active part in the Massachusetts Total Abstinence Society from its beginning. He was involved in creating excursions for poor city children, including to Walden. In 1874, to kickstart a fundraising campaign for the debt-ridden Appleton Temporary Home for Inebriates, he offered to pay down one-tenth of its debt and to donate $10 yearly for the rest of his life. In 1875, he supplied every school district in his native town of Lunenburg with a cabinet organ and a full set of songbooks and donated money to the Lunenburg farmers’ club to encourage them to plant forest trees. Later, he donated globes and microscopes to the Lunenburg schools. Charles was also one of the founders of the Boston Union Industrial Association whose purpose was to find employment for and give assistance to the poor. [15] Ann (Tyler) Heywood showed up in newspapers in the 1870s, sometimes attending an event with her husband, but sometimes on her own. Ann was a donor to the North End Mission nursery. She served food (as did men) during at least one of the Poor Children’s Excursions to Walden, and in 1875 she and Charles were both appointed to the Committee in charge of Poor Children’s Excursions from the city. Ann served on the committee on her own for several years. In 1876, Mrs. & Mrs. C. L. Heywood were given a seven-piece silver tea service “as a token of appreciation of their generous gift of the reading room to the village of Waverley.” [16] Acton Connection In the 1870s, the Heywoods came to South Acton. As far as we can tell, their involvement started with a business opportunity. In 1869, William Schouler, owner of a South Acton mill, decided to sell out. An ad said “WATER POWER FOR SALE – Consisting of two privileges, within 30 rods of each other, one of 16 and the other of 9 feet tall, on an excellent stream, with a reserve of two ponds of 400 acres, altogether independent of the stream, with good factory buildings and dwelling houses, several acres of land with orchard and large grapery, situated on the Fitchburg Railroad, near the depot at South Acton, about 1 hour’s ride from Boston.” [17] Charles Heywood purchased the property on April 27, 1870 with a mortgage. In November, the old Schouler Mill burned, with damage estimated at $3,000. Fortunately, Charles had it insured. [18] Charles started a soapstone mill at the South Acton site. We were unable to find any details about the soapstone mill, unfortunately. There were soapstone quarries elsewhere in Massachusetts and in Vermont; Charles presumably was able to ship raw materials to Acton easily by rail. We were able to discover some details about Charles’ property from Acton’s 1872 tax valuation: Heywood, C. L., Belmont --

Charles owned water rights and the mill at approximately today’s 115-141 River Street and a house at approximately 140 River Street (no longer standing). The house, probably vacant for much of the year, received the wrong kind of attention in October 1875: “Some malicious person or persons have been throwing rocks through the windows of the house and barn near the soapstone mill, belonging to Supt. Heywood. A reward of $25 is offered for the arrest and conviction of the depredators.” [19] After Charles had paid off his mortgage, he started a new venture that was advertised in the Acton Patriot on September 26, 1878: [20] A NEW Grain & Grist Mill Has been fitted up with Corn Cracker and two sets of Stones at the Soap Stone Mill, on the Wm Schouler place about A half mile east of the South Acton Station, where Corn, Meal, Oats and Shorts will be offered at wholesale and retail at the lowest market price. Corn, Oats and Rye will be purchased in small lots of the farmer if offered. Mr. JOHN D. MOULTON, the well known miller of South Acton, has been employed to take charge. Orders left in order box at T. J. & W.’s Grocery Store will receive prompt attention. C. L. HEYWOOD. South Acton, Sept. 25, 1878 1878 seems to have been a time of change for the Heywoods, and it is likely not a coincidence that they started showing up more and more in Acton during that time. Charles “contributed liberally” to the building of the South Acton Universalist Church that was dedicated on Feb. 21, 1878, and he taught in its Sunday School. In June, he invited the children of the Sunday School there to make small floral bouquets with an accompanying letter that he would take to prisoners in Concord. [21] On August 27 of that year, there was a farewell celebration on the South Acton “grounds of Superintendent C. L. Heywood” for the fifty city children that he had hosted “at his summer home ever since July 1. The people of the vicinity turned out generally to the evening entertainment, which consisted of speaking, illuminations, bonfire, music by the Acton band, fireworks, and a general jollification.” [22] Ann’s role as hostess of fifty children was not mentioned. In 1878, Charles Heywood resigned from the Fitchburg Railroad after a career that lasted about 35 years, including fourteen as Superintendent. He acted in an advisory capacity for the railroad for three more months, but he had many things to do. He was working on new inventions. At the end of the year, he filed five more applications that were primarily aimed at making railroads safer for employees and passengers, including improvements in signal lights, steps for rail cars, and cabooses for brakemen. [23]  Track Clearing Car Track Clearing Car Charles’ gristmill continued. He added a horse shed at the grist mill for his customers’ convenience and ran ads in the Acton Patriot. [24] The Patriot reported on June 26, 1879 that: “Mr. C. L. Heywood and wife are to start Friday evening on an European journey, returning home in September.” [25] That fall, Ann F. Heywood was one of the first six women in Acton to register to vote in local school committee elections. That same fall, Charles was chosen by Acton as one of its delegates to the Republican Convention. During that period, the couple evidently considered South Acton “home”. [26] The 1880 Boston Directory, probably from information given in 1879, shows Charles L. Heywood as president of the Mercantile and Collection Agency of 8 Exchange Place, with a house at South Acton. [27] We have no other information about Charles’ involvement in what seems to have been a precursor to credit rating agencies. Because our collection of newspapers before 1888 is sporadic, we were not able to find any other mention of the Heywoods in Acton. However, the Heywoods showed up elsewhere. After Acton The 1880 census listed Charles and Ann living on Revere Street in Revere with Lincoln (age 11) and a few boarders. Ann continued to help with Poor Children’s Excursions and was elected to the executive committee in 1880. [28] Charles moved on to several new ventures that included contracting to fill what today we could call “wetlands,” but at the time were considered public health “nuisances.” Charles served as a director and then president of the Maverick Land Company that was filling the flats in East Boston that were expected in early 1881 to “be much required for railroad purposes during the coming year, and can be sold to advantage.” [29] Charles was involved with filling land at Fresh Pond in Cambridge and also apparently got involved in the project to fill Prison Point in Charlestown for the Eastern Railroad that seems to have been a quagmire for all parties. That scheme supposedly brought financial reverses to Charles, although we were not able to confirm that story. In addition to filling projects, he was involved with the Hoosac Tunnel Dock and Elevator Company and the Union Electric Signal Company. [30] Charles received a patent for an improved Track Clearing Car on April 11, 1882. Presumably, he continued to promote his inventions and in early 1883 took an extended trip to the West and Southwest and went to the National Exposition of Railway Appliances in Chicago where he was exhibiting his inventions. [31] Charles continued to support causes that he believed in. He served for eight years as treasurer of the Massachusetts Total Abstinence Society and lent his public support to the cause when needed. He continued working to help poor children and discharged convicts. Somehow, Charles found the time in November 1882 to present a travelogue to the Farmers’ Club in his native town. [32] In 1883, Charles went to work managing the construction of quarantine grounds in Waltham along the Fitchburg railroad. The quarantine grounds were to keep cattle, imported for breeding purposes, safely away from native stock. According to the Globe, the project was part of an effort by the federal government to systematically create an efficient quarantine system. [33] On June 23, 1883, Charles had been in Waltham, attending to his duties at the quarantine station. At about 4 o’clock in the afternoon, apparently trying to get to the station that would take him home to Waverly (Belmont), he was walking on one of the tracks. Reports vary; he may have been distracted by trying to warn another man that a passenger train was coming, or he may have been unaware that a freight train was running in a different direction from usual. Whatever the details, Charles, whose career and inventions had been aimed at improving railroad safety, was struck by a freight train. He was rushed to the main Waltham depot, attended by local doctors, and then taken by special train to Massachusetts General Hospital. Unfortunately, he died almost immediately after arriving at the hospital. [34] Charles’ death was a shock to many and was widely reported in the news. He was something of a celebrity and was widely admired for his success and generosity. Most reports, typically, either did not mention Ann at all or simply stated that he had left “a widow.” However, a couple of reports mentioned Ann as a person: “His wife was an estimable lady, and by her kindly encouragement has done much to make him what he was,” [35] and, probably from the same source, “Accompanying all the talk about the sad affair and the inquiries for particulars relating thereto were a general expression of regret and sympathy for his widow, who is a lady held in the highest estimation, and to whose efforts, it is said, has been due the greater part of her husband’s success.” [36] Ann Heywood’s life obviously would have been severely upended by her husband’s death. She had a teenaged son to care for and, most likely, a complicated set of financial entanglements left by her husband’s unexpected demise. Charles left an unusually long will dated June 20, 1878. In addition to providing for Ann, he created a trust for the benefit of his newly adopted son Lincoln and any wife, widow, or children Lincoln might have in the future. Given Charles’ ability to plan ahead, it is not surprising that there were many contingencies and potential recipients of money, including relatives and charities. Charles, who only had the benefit of education in the local schoolhouse, added, “I wish my said son to have the opportunity of obtaining, if he desires it, a liberal education, and, while I do not restrict his selection of a college or university, yet I would request that he should, before deciding, carefully consider the advantages afforded by the Massachusetts Agricultural College at Amherst.” He also left an additional special $2,000 trust, the income of which would be paid to Lincoln until the age of 25, at which time he would get the principal. The will directed that the income and the principal of that trust should be given by Lincoln “to Charitable objects, suggesting to him as worthy of special attention that class of the poor who bear in silence the burden of poverty, sometimes styled the silent poor.” Charles clearly hoped to train Lincoln in charitable giving. [37] In 1884, Ann and son Lincoln moved to Pawtucket, RI where Lincoln attended high school. Lincoln graduated with the class of 1886 and then attended Brown University for two years as a member of the class of 1890. In 1889, he entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and graduated in 1891 as a civil engineer. His senior thesis, completed with another student, was “A Plan for Widening a Stone Highway Bridge at Pawtucket, R. I.” After graduation, Lincoln again lived with his mother and worked for the Interstate Street Railway Company as an engineer. He married Edith Clapp on December 15, 1892. In July 1893, he became engineer of the town of Lincoln, RI and started working on designing and constructing a sewer system for part of the town and on creating a complete and coordinated system for the whole town. He and Edith had a baby daughter Hortense. Tragically, Lincoln died on Jan. 12, 1895. After what happened to his adoptive father, safety-minded railroad executive Charles, it was striking to read that Lincoln died of a disease that he was working to protect others from. “Mr. Heywood was taken ill the last of December with that dread disease, typhoid fever, which he, in common with many other engineers, through the agency of pure water supplies and proper sewerage systems, had been striving to render less dangerous to the community and less likely to become epidemic in thickly settled districts.” [38] He was 26 years old. One can only imagine the blow to his mother Ann, as well as to his wife. Joint owners of their home at Brook and Grove streets, Ann and Edith Heywood sold the property in early 1896. The 1896 Pawtucket Directory listed Mrs. Ann F. Heywood as having “removed to Providence.” [39] The 1900 census showed Ann F. Haywood (a widow born in Massachusetts in June 1825) as a boarder in the household of Anna Burrill in Concord, MA. She may have simply been staying for the summer, because the 1901 Providence, RI Directory shows Ann living at 733 Cranston Street. [40] We are not sure where she lived for the next few years, but Ann was in Pawtucket, RI when she died on November 14, 1904 of a cerebral hemorrhage. She was buried with Charles at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, MA. We found a death notice for Ann, but no full obituary. [41] On the other hand, we found that Charles was still notable enough in 1904 that a newspaper profile of a former Lunenburg teacher mentioned that he had taught “Charles L. Heywood, afterwards superintendent of the Fitchburg railroad.” [42] Sadly, that fame is long gone. In South Acton, though the railroad tracks remain and water still runs through the site, passersby would probably have no idea that mills were once there and that across the street, a generous couple once hosted dozens of city children in the summertime. References: [1] Boston Sunday Herald, June 24, 1883, p. 2; Fitchburg Railroad. Report of Committee of Investigation. Boston: Henry W. Dutton & Son, 1857, p. 6 [2] Brigham, Willard. The Tyler Genealogy; The Descendants of Job Tyler, of Andover, Massachusetts, 1619-1700. Privately published by Cornelius and Rollin Tyler, 1912, page 223 [3] Boston Evening Transcript, Sept. 17, 1864, p. 5 [4] For an overview of the Walden park, see Thorson, Robert M. The Guide to Walden Pond. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018, p. 167-168 and Springfield Republican, July 14, 1866, p. 1. For names, see among others: Boston Globe, July 3, 1874, p. 2; Lowell Daily Citizen & News, June 15, 1867, p. 2; Boston Journal, Aug. 24, 1866, p. 2. [5] Waltham Sentinel, Sept. 14, 1866, p. 2 [6] Waltham Sentinel, Nov. 30, 1866, p. 2 [7] Among many other reports of the park: Waltham Sentinel, June 4, 1869, p. 2; Boston Traveler, July 3, 1869, p. 2; Boston Journal, Sept. 1, 1870, p.4; Lowell Daily Citizen and News, July 14, 1870, p.1; Boston Daily Advertiser, Aug. 19, 1873, p. 1 [8] Boston Globe, May 8, 1875, p. 5; Boston Post, July 10, 1874, p. 4; National Aegis, Sept. 4, 1875, p. 3 [9] Patents #51,829 and 62,197; Railroad Gazette, Chicago, Vol. 2, No. 1, Oct. 1, 1870, p. 8 and Vol. 9, Jan. 26, 1877, p. xii; Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association. Exhibition Catalogue, September, 1865. Boston: Wright & Potter, 1865, p. 12 [10] Report of the Railroad Commissioners of the State of Maine, for the Year 1871. Augusta, Maine: Sprague, Owen & Nash, 1872, p. 46 [11] Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association. Exhibition Catalogue, September, 1865. Boston: Wright & Potter, 1865, p. 12; United States Centennial Commission. International Exhibition 1876 Official Catalogue. John R. Nagle and Company, 1876. In the Machinery Department, Charles’ Bridge Guard was #939c, but he seems to have had at least one other invention exhibited, #778c. [12] Boston Herald, June 25, 1883, p. 2 [13] Boston Traveler, May 11, 1869, p. 4 [14] Waltham Sentinel, Nov. 4, 1870, p.2; Boston Daily Advertiser, Jan. 7, 1870, p. 1; Boston Globe, May 25, 1875, p. 1; Boston Herald, May 30, 1883, p. 4; Cunningham, George A. History of the Town of Lunenburg. Vol. II, no publisher, p. 393; Waltham Sentinel, Dec. 22, 1865, p. 2 [15] Among others: Boston Journal, Nov. 14, 1871, p. 2; Boston Globe, March 26, 1873, p. 8, Boston Journal, March 25, 1879, p. 3; Boston Globe, Feb. 6, 1873, p. 8; Lowell Daily Citizen and News, Feb. 5, 1874, p. 2; Boston Journal, Sept. 12, 1883, p. 1; Boston Globe, July 3, 1874, p.5; Boston Daily Advertiser, Sept. 2, 1874, p. 4; Boston Globe, Feb. 10, 1875, p. 7; Boston Daily Advertiser, Sept. 14, 1875, p. 4; Fitchburg Sentinel, June 28, 1883, p.2; Boston Post, March 18, 1875, p.3; [16] Boston Traveler, Feb. 23, 1876, p. 4; Boston Journal, March 2, 1877, p. 2; Boston Daily Advertiser, Aug. 19, 1873, p. 1; Boston Globe, May 5, 1875, p. 4; Boston Daily Advertiser, March 15, 1878, p. 4 [17] Boston Journal, Dec. 17, 1869, p. 3 [18] Middlesex County Deeds, Vol. 1119, page 230-235 shows the purchase and the mortgage in April 1870. Vol. 1421, p. 280 records the discharge of the mortgage in January, 1877.; Lowell Daily Citizen and News, Nov. 19, 1870, p. 2 [19] Acton Patriot, Oct. 9, 1875, unpaginated [20] Acton Patriot, Sept. 26, 1878, unpaginated [21] Undated clipping in scrapbook at Jenks Library; Boston Sunday Herald, June 24, 1883, p. 2; Acton Patriot, June 13, 1878, p. 1 [22] Boston Daily Advertiser, August 28, 1878, p. 4 [23] Patents #216,403 - 216,307, all filed Dec. 24, 1878 [24] Acton Patriot, Dec. 5, 1878, p. 1; April 17, 1879, p.8; Feb. 19. 1880, unpaginated [25] Acton Patriot, June 26, 1879, p. 1 [26] Acton Patriot, October 2, 1879, p. 8; Boston Journal, Sept. 15, 1879, p.2 [27] The Boston Directory. No. LXXVI. Boston: Sampson, Davenport and Company, 1880, p. 471 [28] Boston Post, June 5, 1880, p. 3 [29] Boston Journal, Feb. 28, 1881, p. 1; The Boston Directory. No. LXXIX. Boston: Sampson, Davenport, and Company, 1883, p. 522 [30] Boston Sunday Herald, June 24, 1883, p. 2; Boston Sunday Herold, June 24, 1883, p. 2 [31] Patent #256,140; National exposition of railway appliances, Chicago, 1883. Guide to the National Exposition of Railway Appliances, Chicago (May 24-June 23, 1883). Chicago: Rand, McNally & Co., 1883, p. 93; Boston Sunday Herold, June 24, 1883, p. 2 [32] Boston Journal, Sept. 12, 1883, p. 1 and Dec. 12, 1881, p. 2; Boston Globe, Aug. 31, 1883, p. 2; Boston Herald, May 30, 1883, p. 4; Fitchburg Sentinel, Nov. 16, 1882, p. 2 [33] Boston Globe, April 18, 1883, p. 2 [34] Boston Globe, June 24, 1883, p. 1; Boston Sunday Herold, June 24, 1883, p. 2; Fitchburg Sentinel, June 26, 1883, p. 3 [35] Boston Globe, June 24, 1883, p. 1 [36] Boston Sunday Herold, June 24, 1883, p. 2 [37] Middlesex County Probate, #15,946 [38] George A. Carpenter and Morris Knowles. Lincoln C. Heywood A Memoir. Journal of the Association of Engineering Societies, Volume 14, p.56-57. Read to the Boston Society of Civil Engineers, March 20, 1895. See also The Tech, Vol. XIV, No. 17, Feb. 17, 1895, p. 170 and 172; Evening Times, (Pawtucket, RI), Jan. 12, 1895, p. 1 [39] Evening Times, (Pawtucket, RI), Jan. 25, 1896, p. 6; The Pawtucket City and Central Falls City Directory. No. XXVIII. Providence: Sampson, Murdock & Co, 1896, p. 236 [40] The Providence Directory. No. LXI. Providence, RI: Sampson, Murdock, & Co., p. 440. [41] Evening Times, (Pawtucket, RI), Nov. 15, 1904, p. 4 [42] Boston Sunday Post, Dec. 4, 1904, p. 6 [43] A correspondent granted us permission to use this photograph, which we gratefully acknowledge. 3/11/2020 Acton's First Women VotersKnowing that U.S. women gained the right to vote in 1920, it comes as a surprise to many of us that in 1879, Massachusetts passed a law that allowed women to register to vote for their local school committee. It was a very limited victory, and the journey to full voting rights was long. (See our blog post about Acton women and the 1895 referendum on municipal suffrage.) Up until now, though we knew that there were some women who voted locally and supported women’s suffrage on a broader scale, we have not known who they were. Recently, in the process of digitizing our wonderful but fragile collection of old newspapers at Jenks Library, we made a discovery. On October 2, 1879, the Acton Patriot announced the names of the first ladies registered to vote in Acton, all of whom were residents of South Acton (p. 8). In honor of Women’s History Month, we salute: The fact that these women registered to vote made them quite unusual. Only a small percentage of women did. Suggested reasons for most women's non-participation have included the social expectations of the Victorian era, poll taxes, or lack of interest in strictly local affairs. Given Acton's history of "spirited discussion" of school matters, the latter would be surprising.