|

While researching the Spanish American war, we found a surprising local news item in the Concord Enterprise (July 21, 1898, page 8): “...the buildings of the American Powder Co of Acton have been under constant surveillance night and day by guards... It is said that persons supposed to be spies have been seen the last few weeks in the vicinity of the works in the night hours and it is generally supposed that Spanish spies have been around.” The excitement seems to have abated quickly, but there was plenty of other powder mill news in Acton in that period.

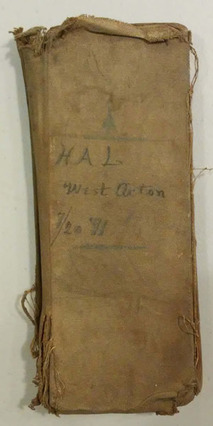

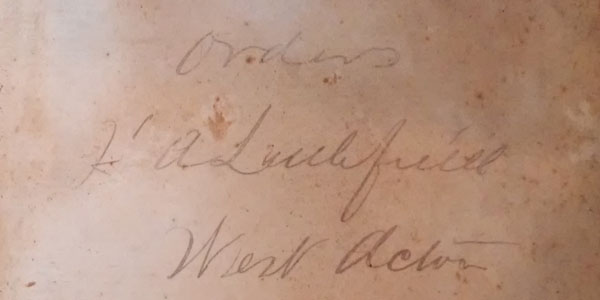

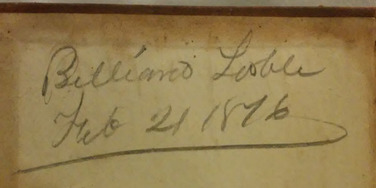

Powder had been made in Acton since the 1830s. In the 1890s, the American Powder Mills ran a large operation at the intersection of the towns of Acton, Maynard, Sudbury and Concord. High demand for smokeless powder led another firm to locate in Acton. In May, 1898, the Enterprise announced that the New York and New England Titanic Smokeless Powder Company was building a plant in South Acton in John Fletcher’s pasture near Rocky Brook and Parker’s crossing on the Fitchburg railroad. The building was to be approximately 100 x 20 feet with one story for manufacturing, and there would be a storehouse (presumably separate). The product would be “Titanic smokeless” powder. The paper noted, “There is but little danger in the making of this powder.” (May 19, page 8) The firm obtained government orders, and the Fitchburg Railroad added a track to the mill site. Open for business around the beginning of September, the company immediately realized that the installed machinery was not suitable and would have to be replaced. The factory finally started work around the end of October. After only a week of operation, the mill blew up. (Nov. 3, page 8) The cause was uncertain, but one of the men working inside noticed something was wrong with the machinery and was able to alert the others in time for everyone to escape. Employee Dyer had to make his way out through fire, but with the help of the others, removed his burning clothing and was mostly unharmed. The Enterprise assured the public that “The buildings were thoroughly made and everything was in first class order,” probably addressing a common question about the cause. A previous article had mentioned that “work on the new powder mill is rushing.” (May 26, page 8) The company rebuilt. In fact, the Enterprise noted that the explosion had provided winter employment for a fair number of people in South Acton. (Jan. 19, 1899, page 8] In February, 1899, the powder mill was pronounced to be sound and ready to work. “We wish them better luck than last time,” wrote the Enterprise (Feb. 8, page 7). Sadly, by the end of the year, the New York & New England Titanic Smokeless Powder Company was in involuntary bankruptcy (Enterprise, Dec. 21, 1899, page 11 and Boston Sunday Globe, Dec. 17, 1899 page 21). The machinery was sold off to people from Nashua, NH (Enterprise, Sept. 8, 1900, page 8). We did not find out what happened to the building. Meanwhile, the well-established American Powder mills nearby were having their own excitement. The Concord Junction news in the January 27, 1898 Enterprise (page 5) mentioned that an explosion at the powder mill had been felt, though we could not find details or confirmation anywhere else. In early September, 1899, the company’s “Wheel Mill No. 5” blew up, followed quickly by No. 4. (Enterprise, Sept. 7, 1899, p. 4) The manufacturing process involved grinding powder between two enormous wheels that were powered, by 1899, by electricity. In this case, about five hundred pounds of powder in the two mills exploded, but fortunately there was no loss of life. A little over a month later, it was discovered that in the very early hours of Saturday morning October 14, someone had created a 125-foot long trail of powder from the woods behind the property, along a plank walk and the railroad tracks, to “the pulverizing mill which was in operation. The air was surcharged with powder and the slightest spark would have caused an explosion which would have blown all the surrounding buildings into atoms” along with the eight men working there. (Enterprise, Oct. 19, 1899, p. 6) Luckily, the powder burned out before reaching the mill. The case was not hard to crack; a disgruntled worker’s face had been severely burned from his attempt. Though at first he only acknowledged being in the woods and drinking, eventually he pleaded guilty. (Lowell Sun, Oct. 16, page 4 and Oct. 21, pm edition page 1; Enterprise, Oct. 19, page 6) There really was no need for spies around Acton’s powder mills; they were dangerous enough places on their own, with malfunctioning equipment and angry workers making the risks even greater. Though it was neither the first nor the last time Acton’s powder industry would make the news, 1898 and 1899 were interesting years. 3/1/2017 Morocco in South Acton Periodically, we are asked questions about the Morocco factory in South Acton. Aside from a couple of pictures in the Society’s collection, our information on it is fairly limited, so we decided to do some research into its history. Our first question was what exactly was manufactured in a “Morocco factory.” Though the product is unfamiliar to many of us today, when the South Acton plant was built in 1892, “morocco” would have been recognized widely as a type of leather. According to Cole’s Dictionary of Dry Goods published in that year, true Morocco was made from goatskins, a firm-but-flexible leather product with a grained surface. It was a durable material that was used for high-end book bindings, seat upholstery, and boot-tops. Over time, “morocco” also came to describe an imitation product, lightweight leather made from sheep, lamb, kid, and goatskins, primarily used in manufacturing light shoes. According to Phalen’s History of the Town of Acton, the local morocco factory (or “skin shop”) was built by Elnathan Jones and was run by his son-in-law Charles Kimball. Charles Milton Kimball (1863-1823) was born in Haverhill, Massachusetts to Benjamin Milton and Margie (Johns) Kimball. He married Carrie Evelyn Jones, daughter of Elnathan and Elizabeth (Tuttle) Jones, in South Acton on Sept. 5, 1888. Elnathan Jones was one of the owners of the prosperous and dominant Tuttles, Jones, and Wetherbee enterprise in South Acton. As Charles Kimball’s father-in-law, he may well have influenced the decision to locate in Acton, and the factory was built on Jones's land. What was not apparent from reading Phalen’s history, however, was that South Acton’s morocco business was actually a transplanted family firm from Haverhill. Haverhill had a large concentration of shoe and boot manufacturers and associated leather businesses, among them morocco. Charles M. Kimball’s grandfather Benjamin (c. 1815-1870) was listed as a morocco manufacturer there in the 1850 census. Later, with Charles’ father Benjamin Milton Kimball (1838-1910), he formed B. & B. M. Kimball & Co., morocco manufacturers with a plant in Haverhill and an office in Boston. Charles was eventually brought into the business. In 1888, Charles received a patent for an improvement in the treating of “morocco and other finished skins” that he assigned to his father and himself. As far as we can tell, the Kimballs’ morocco enterprise was large-scale and successful. A glowing report on Kimball and Son was included in a book on Haverhill by its Board of Trade in 1889. According to the write-up, the company occupied three three-story buildings on Fleet Street and one on Pleasant Street, employing 130 people and processing 750,000 skins worth $500,000 yearly. The morocco produced was of a superior grade that would hold color. The company supplied both the local and the Boston markets. Demand was so high that it had just enlarged its plant (as had its competitor Lennox and Briggs). The business was not without bumps, however. In August 1889, the company announced that, breaking with its own tradition but trying to keep up with its competitors, it would no longer pay its employees “by the piece” but would pay weekly wages instead. The company’s morocco dressers objected and about a hundred went on strike. We found news of the strike reported as far away as Shreveport, Louisiana. The strike does not seem to have ruined the company, but there was an incident of sabotage. Haverhill’s Daily Evening Bulletin (September 16, 1889, page 2) reported on “Midnight Scoundrelism.” The previous Saturday night, the main belt that powered the factory was cut into pieces and ruined, necessitating a brief shutdown while it was repaired. Whether labor unrest in Haverhill contributed to the decision to move, we don’t know. So far, the only mention that we have found of a motivation for the move was in Charles’ 1923 obituary, mentioning “the business in Haverhill being incorporated into a larger concern,” implying that they sold out and started again. Whatever inspired the decision, by 1892, they were on the move. On September 16, it was reported in the Concord Enterprise that “Messrs. Kimball & Son of Haverhill will move their morocco manufactory from that city to South Acton as soon as a building can be erected for them. A building seventy-five feet long, three stories high, with an addition sixty [feet] long and one story high has been staked out and the work will be pushed forward as speedily as possible. About fifty hands will be employed in the factory.” By January 5, 1893, the factory was running. The Enterprise reported that those employed so far had come with the business from Haverhill and that the company had “bright prospects and a large number of orders.” A factory inspection report published in January 1894 by the Secretary of the Commonwealth showed that the business was at that point employing 58 men, by far the largest manufacturing enterprise in town. By current standards, leather work was apparently smelly, hazardous, and polluting. No complaints about that appeared in the local paper. On the contrary, a drought in late August of 1894 that necessitated digging a new well at the morocco factory inspired the news that there was “A big haul of fish near the morocco factory. Low water, fish in a hole, scooped out with a rake. Result – eat fish one week.” (Concord Enterprise Aug. 30, 1894, page 8) One has to wonder about the health of the fish. Business was still doing well in 1895 according to the Enterprise, and a week’s stoppage in 1897 was attributed to the company running out of stock due to a delay in a tariff bill, presumably the protectionist Dingley Tariff passed under President McKinley. The first indication that the business might be contracting was found in the Commonwealth’s inspection report published in January 1899 for the previous year. By that time, there only 26 men employed in the morocco business, and the sanitary conditions were graded “fair.” (It was still, however, the largest manufacturer listed in Acton at the time.) In 1900, the company established a new time schedule. From then on, the working hours were 6:30 a.m. to noon and 12:45 p.m. to 6 p.m., with a Saturday closing-time at noon. The schedule was popular with employees for its generous half-holiday on Saturdays according to the Enterprise. The possibility that the change might have resulted from financial concerns was not mentioned. Phalen stated that as public tastes changed, the market for morocco declined. The Boot & Shoe Recorder of August 7, 1901 indicated that there was great uncertainty about what styles would be fashionable in the coming spring season, with some indications that patent leather and canvas were taking over from colored morocco. Perhaps relatedly, the Acton Concord Enterprise reported strikes in four morocco factories in Lynn, MA in November 1901. We found no explicit mention of financial strain in the Kimballs’ business, but an Enterprise article on May 21, 1902 reported that B. M. Kimball & Son, proprietors of the morocco factory, would soon retire. “During the past ten years since their business has been established in town they have done much for its improvement not only from a business standpoint but have also proved themselves true public spirited men. This change only adds to the already unsettled condition of affairs in the village and the future appears anything but clear.” The unsettled condition of the factory continued for several years. Reports would surface in the Concord Enterprise of firms that were taking over or were looking at the factory, including The McLean Mfg. Co. of Boston (August 5, 1903), C. Brandt & Co. leather dressers (April 13, 1904), and several unnamed firms including an aluminum manufacturer (January 23, 1907). At some point, ice cream pails evidently were produced there. Finally, a viable business moved in, Moore and Burgess, (originally named the South Acton Webbing Company, later Moore and Cram), a producer of narrow woven fabrics in cotton and silk (Enterprise, January 22, 1908). It was so successful that it moved to new quarters in West Concord in 1916-17. The South Acton morocco factory eventually was torn down, and, according to Phalen, lumber, bricks and windows were taken by townspeople to incorporate into other buildings, spreading around the town a unique part of Acton’s history. The in-progress Assabet River Rail Trail is expected to go past the factory site. A portion of the Jones land abutting the mill pond has been preserved in the past few years and is known as the Caouette Simeone Farmland. We recently found a copy of an envelope advertising Littlefield’s ANTI-FLY, manufactured by H. A. Littlefield in West Acton, Mass. That name was too enticing to ignore, so we set out to learn more about the business. The envelope stated that Anti-Fly was a liquid concoction harmless to people and animals but discouraging to flies, roaches, ants, bed bugs and more. The enterprising Mr. Littlefield also stated that if there were insufficient postage on the envelope, it should be given to a Cattle Owner. An ad for the product appeared in the August 25, 1898 Concord Enterprise: “Stop the flies tormenting your horses and cows. Make $10.00 extra profit on each cow by using Littlefield’s Anti-Fly. Sold at all stores. If not send to H. A. Littlefield, Manfr, West Acton. 1 qt can, 50c; ½ gal, $1.00; 1 gal, $1.50; 5 gals, $5.00. Sprayer free with every can.” August 10, 1899 ads expanded: “Don’t Let Your Cows dry up during fly time. Anti-Fly keeps up full flow of milk.” and “Lice On Hens. Get rid of them. Use Anti-Fly freely about the roosts and in the nests.” By July 26, 1900, an ad cautioned "Anti-Fly is well known, sure, safe and economical. Don't be imposed upon with any cheap substitute, which in the end costs more and only results in disappointment." As it turns out, the Anti-Fly business had a lot of competition. Online newspapers show ads for other “anti-fly” products all over the country, at least back into the 1880s and on into the early twentieth century. How successful Littlefield’s product was, we aren’t sure. Phalen’s History of the Town of Acton says that the product had an “extensive market both in this country and abroad.” That may have been the case, but we found no newspaper mention of his product outside of the local area, or even locally beyond the 1898-1900 period. We did learn, however, that H. A. Littlefield was a very busy man. Anti-Fly seems only to have been a small part of his business life. Hanson A. Littlefield was born in Boxborough in 1848 to Jacob and Ann Brooks (Raymond) Littlefield. After his marriage in 1869 to Florence M. Preston, he moved to West Acton. His occupation was given as a carpenter in the 1870 Census, a wheelwright in his son Sheldon’s 1878 birth record, and a real estate agent in the 1880 Census. Concord Enterprise ads show that he also worked as an auctioneer. According to Phalen’s History, Hanson Littlefield invented cider jelly and had a business called the Littlefield and Robinson Cider Jelly Manufacturing Company that he sold to his partner in roughly 1884. The Cider Jelly Mill owned by Charles Robinson is documented (on a Walker’s Middlesex County Land Ownership map from 1889 and in Boston Globe and Concord Enterprise newspaper articles), but it seems unlikely that Mr. Littlefield was the inventor of cider jelly. Various unsourced websites indicate that boiled cider (thickened to a syrup) and cider jelly were commonplace in New England. Online searching led to an article in an 1865 journal complaining about an attempt to patent the process of evaporation to make cider jelly. “… we received from Messrs. Corey & Sons, Lima Ind., a very fine sample of cider jelly. It had been made on Cook’s Sorgo Evaporator with Corey’s improvements. … these gentlemen are not the inventors of cider jelly by evaporation. We ate it years before they obtained their patent.” (Sorgo Journal and Farm Machinist, Volume III. Cincinnati, Ohio: Clark Sorgo Machine Company, 1865, page 86). Gail Borden (of New York, inventor of condensed milk) also mentioned the concentration of cider down to a jelly in applying for a patent on his process (#35,919, July 22, 1862). During the time period when Hanson Littlefield’s jelly business might have been in operation, references to cider jelly appeared in newspapers as far away as Iowa. Clearly, Hanson Littlefield did not invent cider jelly, and we did not find any indication that he received a patent for improving the cider jelly-making process. He seems to have moved on to other ventures. The Society has a collection of business records that belonged to Hanson Littlefield that do not even touch on his Anti-Fly and Cider Jelly businesses. Among the records is a promissory note for a billiard table that he purchased on February 21, 1876 and an account book relating to expenses and revenues for a “room.” Entries in the book for various customers detailing billiards, pool, and tobacco indicate that one of his early commercial ventures was running a pool hall. (Cards and dice occasionally appear as well.) The most well-documented of H. A. Littlefield’s enterprises was his store in West Acton. The Society has some of his account books, mostly from the 1880s and 1890s. Those books, Acton town reports, and ads in the Enterprise show that he sold a broad array of items; coffee, tea, baking supplies, spices, fish, fruit, tubs of Vermont butter, canned goods, tobacco, screens, lamp parts and oil, tinware, paints, shellacs, seeds, farming tools, carpets, brooms, horse halters and reins, shirt waists, overalls, corsets, pantaloons, shoes, boots, baseballs and bats, toys, cloth, bluine powder for laundry, dyes, diaries, witch hazel salve, a “One minute Cough Cure”, and even a lot of 300 empty barrels.

One of Littlefield's many ads (Concord Enterprise, May 27, 1892) told potential customers that “We have a fresh, clean lot of groceries and other goods neither flavored with smoke or dirty water, at the lowest possible prices. Buy at home and get good goods, save time and money.” (One has to wonder which competitor’s merchandise he was comparing his own against.) Business was presumably good. Around 1893, Littlefield built a large hall in West Acton where meetings, dances, lectures, and basketball games were held. The store was evidently on the bottom floor, a large community meeting space was above that, and the top floor was the home of the Odd Fellows, of which Littlefield was a member. Hanson Littlefield was elected as an Acton selectman in 1893 and 1903. He was a notary and a justice of the peace, served as animal inspector according to a Concord Enterprise article (May 27, 1892), and was a member of a committee that looked into the town water supply in 1895. He was an active Democrat repeatedly elected to Democratic committee positions. He was appointed as postmaster in West Acton twice, first in 1886 and again in 1893, both times under Democratic president Grover Cleveland. At the time, the position was granted politically and often involved moving the post office to the place of business of the postmaster, undoubtedly bringing more customers into the store. Littlefield was also active in various local organizations, among them the Odd Fellows and the Grange. He and his wife raised a family of seven children. Given his obvious abundant energy and activity, it is amazing to read in his Boston Sunday Globe obituary (Aug 3, 1903, page 2) that Littlefield had been “an invalid for a long time, and had been a great sufferer.” He died on July 28, 1903, his doctor stating that the cause was cancer of a year’s duration. According to the Concord Enterprise (August 5, 1903), business was suspended in West Acton to allow townspeople to attend his funeral. He was buried at Mount Hope Cemetery. Hanson Littlefield was spared having to see his Hall completely destroyed by fire the next year, taking with it the grocery of his successor and all of the Acton Odd Fellows’ records, furnishings, and fraternal items. Given the proximity of the Hall to other buildings, the fire was expected to spread. Other towns’ firefighters had been summoned and were preparing to come to help when news was sent out that the blaze had been brought under control by the Acton firefighters. (The October 29, 1904 Fitchburg Sentinel mentioned that its local firefighters were a bit disappointed not to be able to take their “wild morning ride” by train to join in the fight.) The Odd Fellows Hall was rebuilt in the same location where it can still be seen at the corner of Central and Arlington Streets. Pictures of Littlefield’s Hall seem to be very rare, but we were delighted to find that Eugene L. Hall, whose photographic glass plates were donated to the Society, took two pictures of Littlefield Hall before it burned. 7/1/2016 New England Vise Company RevisitedA reader of our previous post about John Sherman Hoar and his vise company sent us pictures of another vise that has survived amazingly intact, many miles away from Acton. A big thank-you for letting us share the pictures!

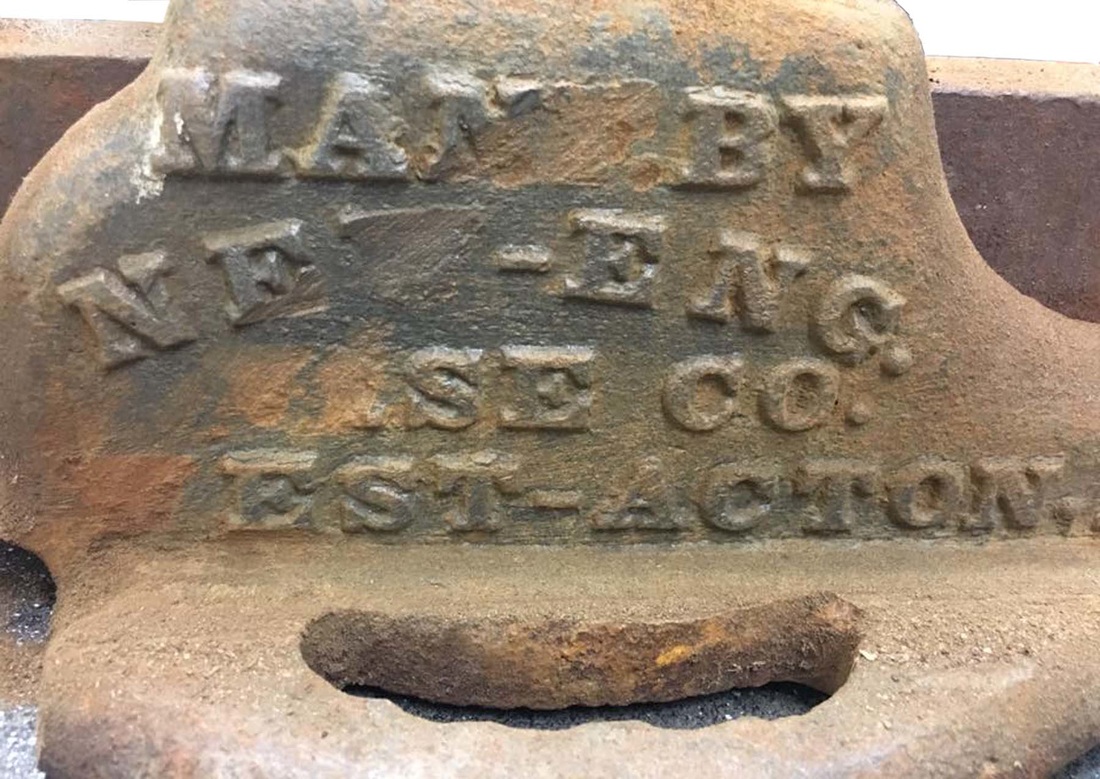

6/9/2016 John Sherman Hoar, Vise InventorA visitor to our Facebook page recently sent us pictures of a vise marked with (filling in a few blanks for worn letters) MAN_. BY NEW - ENG. VISE CO. WEST-ACTON, MASS and HOAR'S PATENT JUNE 19, 1866. Getting ready for the "Made in Acton" exhibit at the Hosmer House museum, we were excited to receive pictures of an Acton-made product that we had never seen before. We wanted to learn about the New England Vise Company of West Acton. Searching the internet led us to the June 19, 1866 patent of John S. Hoar of West Acton (No. 55,656) for an improved rotary bench vise. Online searching of local newspapers and the 1870 Census's manufacturing schedules for information about the vise company was fruitless. (Middlesex County’s manufacturing schedules were not available online, and local online newspaper coverage is sparse in the early years.) Fortunately, we found some useful information in the Society's library. According to an undated newspaper article in a scrapbook in the Society's collection, "The present Pail Factory in West Acton was built in 1867 to manufacture vises. These were the patent of J. Sherman Hoar, of West Acton, and was the first vise ever patented in any country with an off-shot jaw (so called). It could be used on an entire rotary base or on a one-half rotary base. The market for these vises is world-wide. " John Sherman Hoar, born in Boxborough in 1829, was a carpenter who served in the Civil War, joining the 6th Massachusetts, Company E in 1862 with many others from Acton and nearby towns. He came home on disability, having lost his thumb in a gun accident. (This was mentioned in a November 1862 Henry Hapgood letter held by the Society.) Despite his injury, he carried on as a carpenter according to census records. In addition, he turned his attention to inventing a better vise. His patent says that his design gave the vise greater stability and versatility than others in use at the time. According to Phalen's History of the Town of Acton, Hoar's vise made it possible for a workman to hold a long piece of pipe or a wooden rod in a vertical position. In 1867, John Sherman Hoar assigned patent rights to himself, C. Hastings, and N. C. Cutter. Phalen’s History says that he wanted to sell his patent to an interested party, but his partners did not want to sell out. (His partners apparently were Charles Hastings and Nathaniel Cutter. Charles Hastings is listed in Acton's 1870 census as working in a machine shop. N. C. Cutter is harder to find. Bill Klauer's Acton book from the Images of America series contains a photo of the store of Charles Hastings and Nathaniel Cutler; perhaps the Patent Commissioner's 1867 report misspelled N. C.'s surname.) Online versions of published public documents of Massachusetts show that the New England Vise Company of West Acton was organized on January 25, 1868. Improbably enough, searching online, we found a mention in the Galveston (Texas) Daily News of November 15, 1868 that the New England Vise Company of West Acton, Mass. had twenty employees working in their vise manufacturing business. The West Acton vise manufacturing venture was short-lived. According to Phalen, the business was sold to a firm in Fitchburg in 1870. Massachusetts's 1877 Tax Commission's report shows the company still in Fitchburg. Hoar's patent expired around 1884, and the New England Vise Company seems to have been dissolved either in 1892 or by that year, as it was listed as one of the dissolved companies in an 1892 Massachusetts act of law.

John Sherman Hoar only lived for two years after the sale of the company. He died at age 43 of typhoid fever, leaving his wife Lydia (Whitney) and a large family. According to Phalen, one of the prized possessions of John Sherman Hoar's descendants was a model of his vise that he had created from what appeared to be cherry wood. We have no idea how many vises were created in the West Acton factory during its short time in operation. We are very grateful to our Facebook visitor for sharing his vise with us! |

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed