|

4/8/2024 The Page that was MissedResearch for our latest blog post involved searching the 1855 Massachusetts census for all Acton residents who were born in Ireland. Using one of the available online indices, a list could be generated quickly, and then linked images of the census forms allowed us to check each individual’s details and make sure that we had not missed anyone in town born in Ireland. Aside from some creative name-spelling and questions about ages, we thought we had a complete list of Acton’s 1855 Irish-born population. We should have known that the process was too simple.

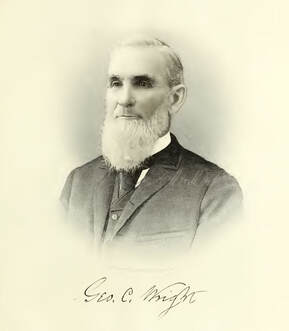

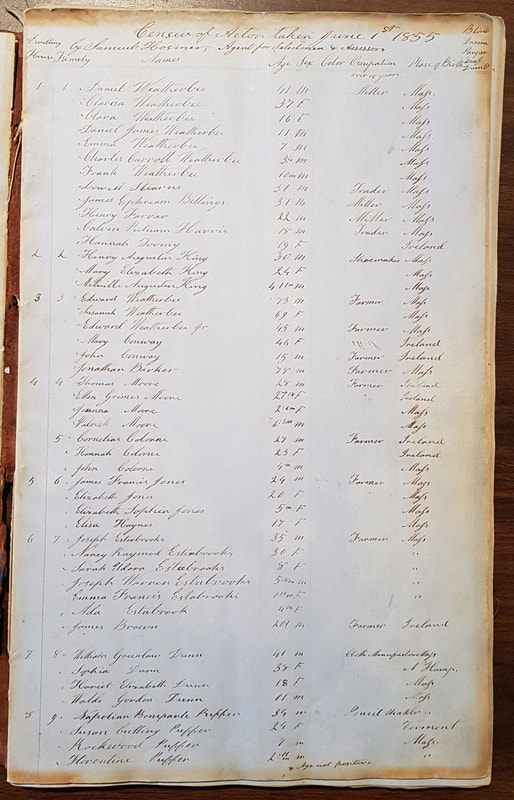

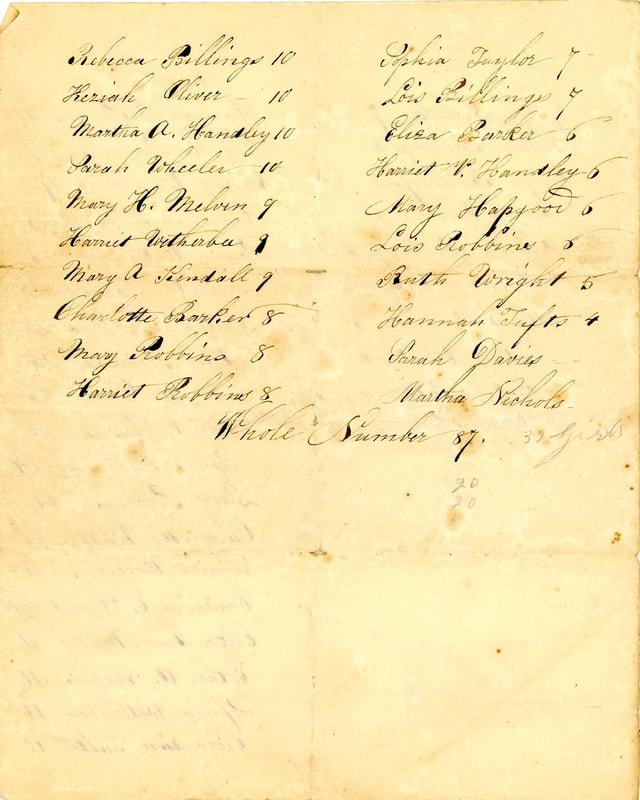

A few years ago, the Society received a donation of a book containing a handwritten “Census of Acton taken June 1st 1855 by Samuel Hosmer, Agent for Selectmen & Assessors.” This 1855 census listing was entirely handwritten, not a set of filled-in census forms. Because we have easy online access to census images through genealogical websites, it had never seemed important to study our census book in detail. While working on the Irish data, however, we took a look at what was actually in the book. To our surprise, on the first page, in the first household, there was a young Irish woman who was not included in our list of Irish-born residents. Thinking that it was perhaps an indexing problem with the spelling of an Irish name, we tried searching the online 1855 census database for the Massachusetts-born individuals in the same household. They were also missing. Moving down the handwritten page, we found that none of the people listed by Samuel Hosmer in the first 6 Acton households, plus part of the seventh, was included in the online index. Three commonly-used online databases gave us the same result; none of them included people from the first 6+ households in our handwritten 1855 census book. The first person who appeared both on our book’s first page and in Ancestry’s 1855 census database was Emma Francis [sic] Estabrooks, age 1 year, 11 months. The online image of the census form showed that Emma was listed on the first line of a filled-in, preprinted Acton census form. There should have been a previous form that listed her parents, but when we tried to access the previous page, we found that there was no image other than the cover of a bound volume Census of Massachusetts 1855, Vol. 19, Middlesex Co., Acton to Cambridge. We had the same result using FamilySearch and another online database; presumably, they all used the same source. (Though stated sources and dates vary somewhat across the different databases, they seem to have come originally from microform/microfilm of the census held at the Massachusetts State Archives.) It appears either that the original filming missed the form that contained the first 6.5 households in Acton’s enumeration or that the first form was actually lost. Either way, the indices and digital images of Acton’s 1855 census that are being used regularly for research are missing 36 Acton residents. We offer here the missing page 1 of Acton’s 1855 census for everyone who is searching for the following 36 individuals. Some were life-long Acton residents, but others only seem to appear in Acton’s census records here. All listed individuals were born in Massachusetts, except as noted. Seven of the missed individuals were born in Ireland. (We included them in our blog post on Irish in 1850s Acton.) Samuel Hosmer’s 1855 Census of Acton: Dwelling & Household 1

Note that the name Weatherbee was more often spelled Wetherbee in Acton. The name Esterbrook(s)/Estabrook(s) is differently spelled even within the same family here and appears in different forms in various Acton records. Further research did not help us to confirm the Irish name Colorne and what other forms it might have taken. Records for other individuals in the 1850s yielded other possible names such as Coborne and Coline. 3/17/2024 Irish in 1850s Acton Source: NASA Earth Observatory Source: NASA Earth Observatory In honor of St. Patrick’s Day, we explored Irish immigration into Acton. The most useful starting point was the 1850 federal and 1855 Massachusetts censuses. Earlier censuses only listed the name of the head of households, usually male. The 1850s listings give us the name of every person in town, as well as their (sometimes approximate) age and birthplace. The population during the 1850s reflects changes in Acton caused both by Irish Famine immigration and the arrival of the railroad. The 1850 census of Acton listed 107 people born in Ireland, or 6.7% of the total population of 1,605. Twenty-five of the Irish-born individuals in Acton were female. (A clear error in the household of Ebenezer Davis Jr. was corrected in our statistics; research showed that the birthplace of Ellen Grimes and Charles Robbins was switched.). The 1850 Acton census gave no occupation for any female, so we can only guess what they were doing. Some women were living with a male who was probably the husband, sometimes with children. In other cases, females lived in a household of a seemingly unrelated family. They probably were doing domestic work. Of the 82 males born in Ireland, almost all who were of working age were laborers (71). Thirty-one were living on a farm and probably working there. Not one of the Irish laborers was listed as a farmer, a term that in the 1850 census apparently was reserved for those whose farm produced more than $100 of products. However, three of the Irish-born men owned real estate that included improved land and buildings. The town’s tax valuation for 1850 shows that John Grimes had 2 acres of improved land, Francis Kinsley had 1.5 acres, and Thomas Kinsley (listed in the 1850 census as Thomas “Wamsley”) had 3 acres. None showed up on the agricultural census for that year. Only three Irish-born men had occupations other than laborer. Twenty-six-year old Nathan Smith was working as a blacksmith for Jonas Blodget. Michael Phaelan was working as a “Switchman” for the railroad, an employer that provided opportunities to many Irish in the nineteenth century. It is very likely that some (or many) of the men listed as laborers worked for the railroad. Finally, Jerry McCarthy was listed as a Boarding House Keeper. Along with (presumably wife) Catherine and two children, he provided a home to eleven Irish laborers. In the 1855 Acton census, there were 111 Irish-born individuals out of a total population of 1,680. The Irish population percentage had not changed much, but the gender mix did. Forty-four were female (39.6% of the Irish-born population, up from 23.3% in 1850). Again, females’ occupations were not noted. Of the 67 Irish men of working age, 27 were listed as “farmer,” a term that seems to have been used in 1855 for anyone working on a farm. (Land ownership was not specified in this state census, although it can be discovered from other sources.) Two Irish-born men were listed simply as “laborer.” The 1855 census specified that 27 men were working on the railroad, almost all as “repairer,” although Michael Phelan was working as a “Switch Tender.” There were eight Irish-born men who had other occupations. Daniel McCarthy was working as a tailor. John Caully (name has possible interpretations such as Canly or Carelly) and Morris Sexton were apparently working at the flannel print works as a “flannel printer” and a ”dyer,” respectively. Michael Falan and Martin Fay were Wood Sawyers, and Thomas Kinsley was a Stone Layer. One has to wonder how the early Irish immigrants were received in Acton. Comparing the 1850 and the 1855 census lists, we found that many people from the earlier list had moved on by 1855. Given significant variations in ages and sometimes in names, it is impossible to match the two lists precisely, but the maximum number that we conjecture might possibly have been on both lists is 23 people. Whether that reflected the climate of the town or simply other opportunities elsewhere, we cannot tell. There may have been a variety of responses to the new arrivals. We do not have a local newspaper available until later, so surviving newspaper reports that were repeated in other places were likely to feature the worst. One such story that circulated in September 1849 accused Acton’s selectmen of shockingly uncharitable treatment of a family of Irish immigrants in crisis. After the story appeared in Boston papers and was picked up in others, Boston’s Daily Evening Transcript reported on an inquiry into the matter and clarified that the tragedy had actually happened in a different town and had not involved Acton’s selectmen at all. (The downside of our having access to digitized old newspapers is that we also have access to old rumors and reporting errors.) Whatever the welcome they received, Acton’s Irish residents proceeded with their lives after the huge upheaval of immigrating. Between 1848 and 1855, 37 children were born in Acton to Irish-born parents. Some Irish-born Acton residents had enough to show up in an 1855 Acton agricultural valuation:

Sources:

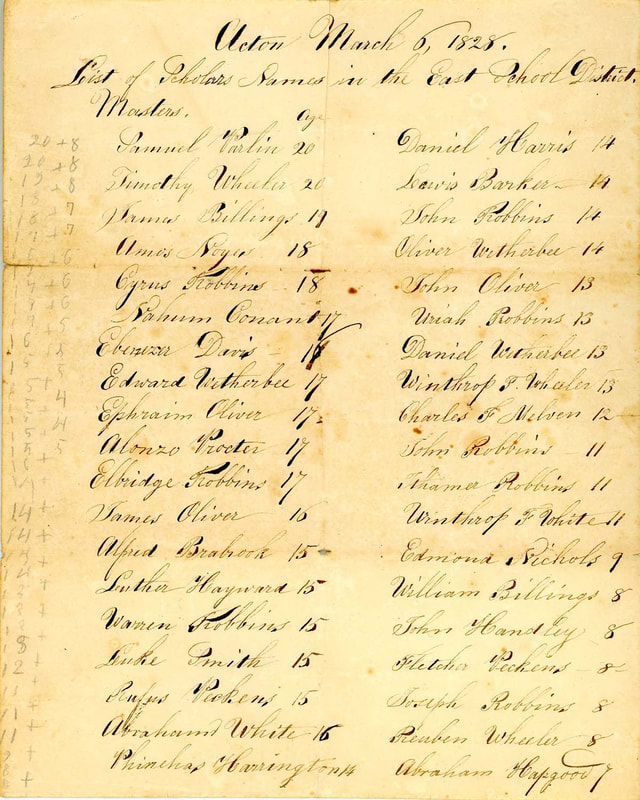

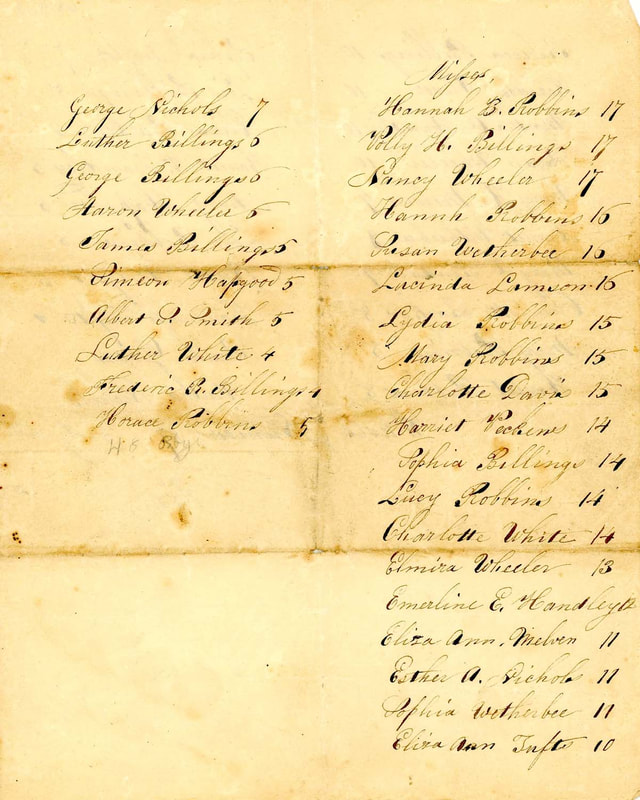

1850 Federal Census of Acton (online) 1855 Massachusetts Census of Acton (online) Census of Acton taken June 1st 1855 by Samuel Hosmer, Agent for Selectmen & Assessors (handwritten) Vital Records of Acton, MA Newspaper articles not actually describing an Acton event: Boston Courier, Sept. 13, 1849, p. 4 Boston Evening Transcript, Sept. 13, 1849, p. 1 The (Springfield) Daily Republican, Sept. 13, 1849, p 2 Boston Daily Evening Transcript, Sept. 20, 1849, p. 2 Salem Gazette, Sept. 21, 1821, p. 2 (quoting Boston Atlas) The (Gettysburg, PA) Star and Banner, Sept. 28, 1849, p. 5 Picture of Ireland courtesy of NASA Earth Observatory, image 49687 1/16/2024 One Crowded ClassroomAs mentioned in a recent blog post on the history of the East Acton school district, during the first decades of the nineteenth century, a one-room schoolhouse at the corner of today’s Great and Davis Roads served students from both North and East Acton. The result, especially in the winter months when farm work was not expected of older students, would have been crowding and a teacher with very little time for individual grades, much less individual students’ needs. Residents of East Acton campaigned for years to split the school. We recently came across a March 6, 1828 listing of all the students in what was then called the “East” School District. On it were the names and ages of 87 students, 48 “Masters” and 39 “Misses.” At a time when censuses listed only heads of household, this is a particularly useful document. In some cases, this is the only record we have found that shows a student’s presence in Acton. Given the age provided in the March 1828 list, some of the students were easy to find in the town’s published birth records. Some, because of a common name or an age that does not quite match dates in the records, were not so clear and needed to be followed up in other records. Baptisms were sometimes done well after birth, so the provided age was less helpful in identifying individuals in those records. In some cases, we could not find the students in any other Acton records, so we had to search farther afield and try to work back to an Acton connection.

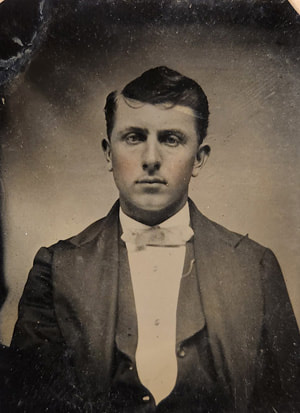

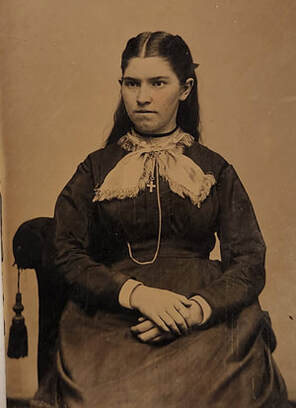

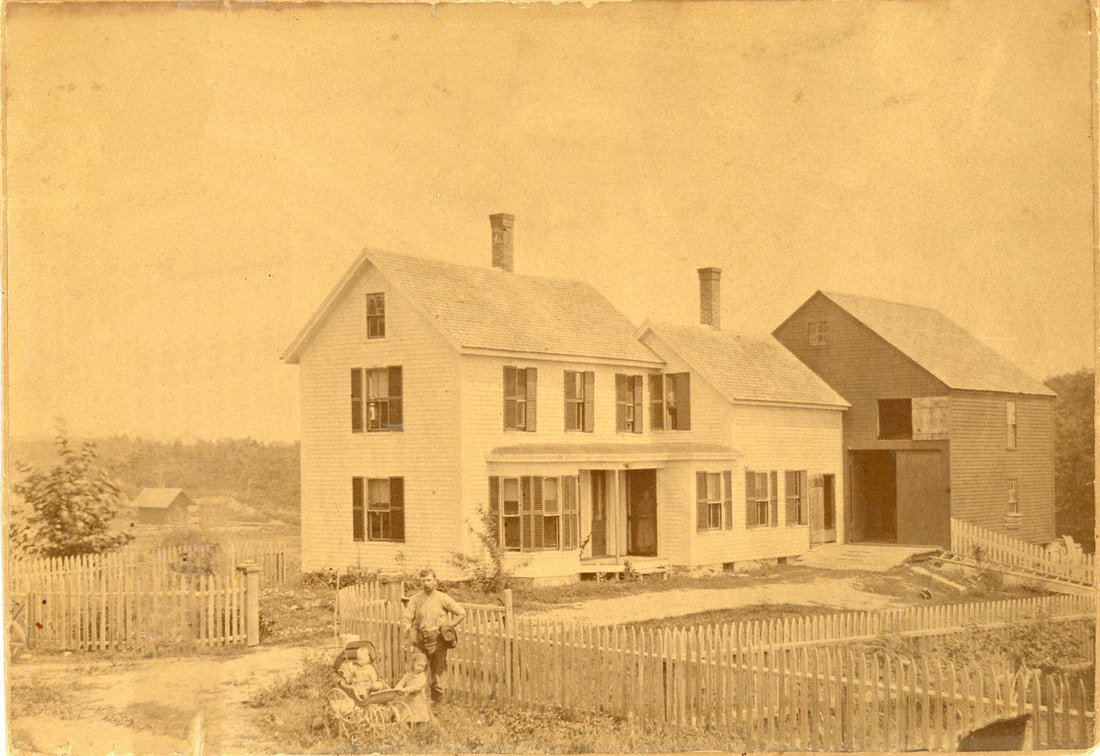

Below is an annotated list of the 87 scholars in the March 1828 East Acton School with the results of our research into their identity. Overall, we found 42 whose name and age seem to match a person in Acton’s birth records and another seven whose age was somewhat off but who probably matched an Acton birth record. For 14 students, we found no birth record in Acton or elsewhere, but we did find a church/baptismal record in Acton that is probably the right person. (Some were baptisms done several years after birth, and some of those were born elsewhere). Research revealed five students whose later records reported an Acton birth, but there is no record of it at the time. We were able to find parents and a likely out-of-town birthplace for eight of the other students. The remaining eleven remain elusive. Ella Miller’s five-year diaries at our Society give us an idea of what life was like for a career Acton schoolteacher at the beginning of the twentieth century. An issue that Ella mentioned often was the complications she faced in getting to and from work. As mentioned in our previous blog post, Ella’s earliest teaching job would have presented few commuting problems. After graduation from Framingham Normal School in the spring of 1896, she started teaching that fall in the same schoolhouse that she had attended in North Acton around the corner from her home. Ella’s time teaching in North Acton was the end of an era. One-room schoolhouses were being consolidated into larger schools. In the fall of 1899, Ella and the students from North Acton were sent to the “Centre” school on Meetinghouse Hill, following the East Acton school that had been closed in 1897. Southeastern Acton students were sent to the South Acton school the year before that. The idea behind the consolidations was that they would improve students’ educational experience by reducing the number of grades a teacher needed to handle. Ella became teacher of the Center school’s intermediate students, with grades 4-6 in her classroom. The move to the Center School, while it may have reduced Ella’s in-classroom complications, added complexity to her travels to and from her North Acton home. The distance was a little less than two miles, by today’s standards a miraculously short commute. In Ella’s day, those miles could be a challenge. Though she lived near train tracks, the trains, even if they came through at the right time, did not go to Acton center. Ella, who would at the diaries’ beginning have been dressed in a long skirt and wearing a corset, found various ways to get to her job. There were days in all seasons when she would walk, either because of nice weather or lack of other options. On some days, she bicycled, and on others, her father gave her a ride in a horse-drawn vehicle. Without weather forecasts, there would have been plenty of room for error. On some days, she optimistically took her “wheel” to school, only to be faced with rain in the afternoon. Even if her father hitched up a horse and took her to work, there were factors to consider. Was there mud, ice, or snow to deal with? Occasionally Ella would mention that the conditions were “so slippery and horse smooth” that the going was extremely difficult; the horse’s shoes had to match road conditions. There was also an important decision to make about whether to take a wheeled vehicle or use “runners” for going over snow. Once choices were made, occasional mishaps were inevitable. In Jan. 1909, she reported that she had gone to school in the sleigh, but the going was rough. On one memorable day in Feb. 1911, a man who sometimes worked on the Miller farm took Ella in the sleigh. En route, “a runner broke & lowered my side to the ground. Came back and went in the wagon.” The following day, the sleigh went to the blacksmith’s shop. The Millers put their “democrat” wagon on runners, and after that it was “fine sleighing.” As snow receded, road conditions were variable and a real challenge. She walked home on Feb. 26 and 27, 1914 and said “Rather hard walking because snow is getting soft & makes it slumpy.” Then came mud season. On March 8, 1912, Ella wrote “Getting muddy but snow lingers in patches, slippery in shady places on the road.” On March 31, 1918, she wrote “A bad mud spot for autos just north of the house. Pa had to help Mr. Park of Chelmsford out with the horse & warned others.” The following March, Ella noted that there was “an auto stuck in the mud for 2 hours out here toward dusk.” Sometimes, other people made the roads even worse. In December 1914, Ella noted that “The trucks carrying Halls’ logs are making bad work of the roads, especially down beyond Hollowells”. When, finally, the roads dried up, Ella could ride her bicycle to school. Ella would note in her diary when she took her first spring ride. Not surprisingly, she would occasionally have issues with her bicycle. The second day of school in September 1908, her pedal came off, and there were inevitable problems with wheels and tires. Her neighbor Elmer Cheney often helped her with repairs, putting in a new valve or adding “Neverleak” to a tire. Sometimes if it rained after school, she would ride home anyway. She was a hardy person, but even she mentioned at the end of October 1914 that she’d gotten chilled coming home on her bicycle. (There was a little snow that morning, and it reached 33 degrees at night). She must have been particularly determined (or desperate) on Dec. 2, 1918 when she rode her bicycle at 16 degrees. The one option that Ella had for public transportation was to take the “barge” that the town provided for students from outlying areas to get to school. The barge was horse-drawn and provided (some) protection from the weather. Ella seems to have made a practice of taking the barge only when it was particularly needed. She mentioned conditions that induced her to take the barge; muddy roads, rain, thunder and high wind, sub-zero temperatures, a major snowstorm, and her family horse being lame. On May 11, 1917 she wrote that she “came home in barge every night, partly because of ironing, cooking, weather & Aunt Eliza being here.” Riding the barge was not a perfect commuting solution. The barge drivers had the same issues with deciding between wheels and runners as did the Millers. Some days were tough going. Children’s absences were often blamed on late barges, but Ella couldn’t afford to be late. On March 6, 1923, Ella reported that the “East Acton school barge tipped over yesterday morning on the way to school and several children had slight bruises.” There were also occasional behavioral incidents during the trips. On Feb. 8, 1912, Superintendent Hill came to school at Ella’s request to talk with a student “about his immoral language in the barge.” On December 15, 1921, Ella reported “Trouble in the North Acton barge going home last night – Boys pounding Kathleen so she didn’t come to school.” That incident led to another superintendent’s visit. By the 1910s, some people in Ella’s acquaintance had bought automobiles. Superintendents in early days covered multiple towns. In 1910, superintendent Frank Hill supervised Acton, Littleton and Westford. The 1911 reorganization of the district to include Carlisle seems to have become too much, and Mr. Hill started making his trek by auto. In April 1915, Ella’s co-teacher and friend Martha Smith got an automobile. In the later 1910s, Ella would sometimes get rides get rides from Miss Smith and others. Over the years of Ella’s diaries, it is interesting to note that while some, like the Smiths, started traveling by auto, the horse remained the means of transportation for many. As late as January 1926, Ella noted that it was icy for autos that morning, so “Pa got horse sharpened.” Even though cars would have solved many commuting problems, they added their own as well. In 1917, Ella mentioned that “Miss Smith wrenched her back cranking auto last night. Feeling mean but came to school.” (Mean was Ella’s term for sick or sore.) On two other occasions, Ella mentioned men breaking an arm while cranking their automobiles. Other teachers had their own commuting issues. Those who were living in other towns might rely on trains. Ella noted in Dec. 1917 that Miss Barrett had not gotten to school until 9 o’clock because her train was late and she missed the barge at East Acton. Ella’s father picked her up with horse power. Miss Durkee, an hour late in March 1920, had resorted to snowshoes to get to school. Whatever the mode of transportation, the condition of the roads mattered. Ella occasionally mentioned men working on the road, macadamizing (putting down gravel) or tarring. Snow clearing was a perpetual problem. In Feb. 1920, a storm dropped so much snow that men including Ella’s father shoveled the road by hand to make it wide enough for an auto. Later that week, Ella mentioned her father shoveling the North Acton driveway where drifts were four feet deep. A particularly memorable road issue was caused by the Freeman family in 1914. On Sept. 6, Ella reported that Mr. Freeman had bought a little house and was going to move it onto Ruth Robbins’ North Acton land. At various times in October, Ella would mention which part of the road was affected that day. On Oct. 8, Ella mentioned that it was right across the road that evening. A week later, it was half way to the brook. On the 19th, “Freeman’s house is at the brook, so we go by through the brook.” The next day, “Freeman’s house was almost at the corner so we could go around the triangle.” On Sunday the 25th, “The autos have been very thick by here today & yesterday afternoon because Freeman’s house still blocks the state road.” Presumably the house reached its destination soon thereafter, because the traffic reports stopped.  Miller Home, 32 Concord Road Miller Home, 32 Concord Road A New Commute, Twice In 1919, Ella’s mother passed away. It was time for a change. Ella bought a house just outside the center at 32 Concord Road. For a while, the family went “down home” to the farm periodically. There was a time when the property was rented, but eventually a buyer was found. The move to Concord Road would have made Ella’s commuting to the Center School considerably easier. Snowy days were still a problem, of course. In January 1923, Ella tried skiing and liked it enough to buy skis of her own. She used them occasionally to get to work on days such as Jan. 15, 1923 when it was snowing hard and the barges had difficulty getting through. She learned later that winter that skis might not be so useful for getting home if the snow had softened up. The horse-drawn school barges were replaced by school busses in the fall of 1923. In the winter of 1924 and 1925, Ella mentioned that the busses had trouble getting through snow-filled roads and brought the children over an hour late. In Jan. 1925, a bus got stuck on “Pope’s Road” and didn’t deliver the last children home until 6:30 pm. Ella never mentioned missing the old sleighs in the winter, but it might have occurred to her. Ironically, after moving closer to her work, Ella’s commute became longer again in 1926. After years of contention (see blog post), Acton finally had managed to agree to build a high school that opened up at Kelley’s corner on January 11, 1926. On March 1, 1926, the 7th grade went to that building with Ella as their teacher. Ella’s father borrowed the Smiths’ horse and took her to school that day. On the 10th and the 15th, Ella mentioned that the roads were slippery for the horse to cope with. On the 18th, a neighbor gave Pa some “never-slip” shoes for the horse that were put on by the blacksmith. Ella’s sister Loraine gave her a ride to and from work on the 16th, and that may have convinced Ella to buy her own car on the 20th, a Ford coupe (known to us as a Model T). Driving lessons followed from friends and her sister. Ella mentioned learning to back up and turn around in the field below the cemetery and practicing turning around “up on edge of Boxboro, at Mr. Tenney’s, Miss Conant’s, Taylor’s store & schoolyard.” Her father continued taking her by horsepower, but as the new school year began, on Sept. 7, 1926, Ella wrote that she began going back and forth in her own car. The freedom must have been welcome, although later entries showed that Ella started having familiar-sounding problems. As cold weather arrived, her car wouldn’t start. She got chains for her tires and needed repeated charges for her battery. Water, alcohol and glycerin were put into the radiator and taken out again. On one ride, she noticed her steering wheel wobbling badly. At other times, her foot pedals needed adjusting, and there were issues with her generator. At the beginning of the next school year she reported, “Had a new experience with the car – couldn’t start it without pushing because something locked.” That was soon followed by “Had the brakes + lights on my car tested by Harold Coughlin. One headlight was not working – a surprise to me.” In October, after a teachers’ meeting, Ella had to ask the superintendent to crank her car, not an ideal work situation. We are missing Ella’s 1928-1932 diary, so we don’t know many of the details from those years. Driving must not have been a perfect solution for Ella. We learned from the Superintendent’s annual report that Ella moved back to the Center school, “nearer her home” in the fall of 1931. A relative newcomer, the superintendent reported that “at Acton Centre all teachers are new to the building,” which must have amused Ella after her many years there. She became principal of the Center school, and Marion Towne took over the seventh grade in the high school building. By the time Ella was writing in her final diary, 1933-1935, she made a practice of not registering her car until April. She would find other ways to get to school in the winter months. (She did mention that the weather would have allowed her to take the car to school every day in January 1933 if it had been registered.) By March 1933, signs of her failing health were beginning to show. Ella, who had amazing energy in her younger days, mentioned that she was getting winded walking to and from school. Mr. Fobes started transporting her, for which she was grateful. Ella continued to drive in better weather. Two of Ella’s final diary entries related to her car. On May 16, 1935, she got an oil change and the next day she wrote “All in tonight. Managed to take car to W. Acton by appointment & left to be tested and brakes relined & for them to bring home.” Sadly, that seems to have been her last excursion. By then, her heart was apparently giving out. Her diary entries stopped on May 25, and, as her sister Loraine noted in the diary later, “Ella’s work ended” on June 4. The Centre Grammar School was closed during part of the next day so that her pupils could attend her funeral. At age 57, she had been the oldest and the longest-serving teacher in Acton. 1/20/2023 Ella Lizzie Miller, Acton DiaristAs mentioned in our previous blog post, diaries can be a wonderful source of information about Acton in former days. At the Society’s Jenks Library, we are lucky to have a set of five-year diaries starting in 1908 kept by Ella Lizzie Miller, an Acton native who spent her nearly 39-year career teaching in Acton’s schools. Miller descendants have been very generous over the years, supplying our Society not only with Ella’s diaries, but with pictures, postcards, letters, memoirs, autograph books, and other items from the Miller family’s years in town. Before delving into the diaries, it seemed worthwhile to do some background research on Ella’s early life and her family. Ella Lizzie Miller was the eldest child of Charles Isaac Miller and Lucy Elizabeth Keyes. Charles was born on Aug. 24, 1850 in Sudbury, Vermont. His father Samuel Cooley Miller died in 1852 of sepsis from a cut on his finger. The 1860 census shows Charles living with his mother, his Miller grandmother, and two siblings in Sudbury, VT. In April 1871, Charles was (supposedly temporarily) working as a brakeman for the Northern Railroad, coupling railroad cars of a freight train at Canaan, NH. His right arm got caught, and his arm had to be amputated above the elbow. Newspapers reported details of the accident but also that employees of the railroad presented him with a gift of $91.50. Charles came to North Acton in 1873, around the time that the Nashua & Acton Railroad connected to the very sparsely-populated North Acton, branching off from the Framingham and Lowell that had arrived in 1871. Charles became the North Acton depot master, also serving as telegraph operator, switchman, and signal tender. According to Phalen’s history of Acton he “was so adept at handling freight and express with (his) attached hook that he was ever a marvel to the youngsters of the town.” (page 216) In January 1876, Charles bought from Daniel Harris ten acres between the Framingham and Lowell Railroad and the main road. That July, he bought an additional thirteen acres that went from the “Road to Lowell” (approximately #737 on today’s Main Street) to the “Mill Brook” (Nashoba Brook). The Framingham and Lowell Railroad ran through the land. The thirteen acres had once belonged to Aaron Woods and had been sold at auction the year before. (Aaron Woods' unsought fame was the subject of a previous blog post.) Ella Miller’s mother was Lucy Elizabeth (“Lizzie”) Keyes, born March 22, 1856 in Westford, MA. Her father Edward Keyes had died in South Carolina in August 1865, having served in the Union army for four years. For a while, Lizzie and her mother Lucy Ann (Robinson) lived in Groton with Lizzie’s grandmother. On May 23, 1872, Lizzie’s mother married Acton’s Isaac Train Flagg. Lizzie’s half-sister Edith Flagg was born March 11, 1875, and though Edith became Ella’s aunt, she really was her contemporary. According to family records, Charles Miller married Lucy “Lizzie” Keyes on Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 30, 1876 in North Acton. Four children followed: Ella Lizzie born Sept. 26, 1877, Alice Emma born March 10, 1879, Samuel Elmore born Nov. 25, 1881, and Loraine Esther born Nov. 6, 1884. Ella and her siblings grew up on the farm with the railroad running through their land behind the house, the depot just below, and the North Acton schoolhouse around the corner. The road in front led from Acton Center to Lowell. If Ella kept diaries as a young woman, unfortunately they did not find their way to our Society. We have had to use other sources to put together her early life. She attended the white schoolhouse on what is now Harris Street. A picture from between 1888 and 1890 shows her and Blanche Varney as the oldest of the students taught in the building by Miss Jessie Jones. The Concord Enterprise gives us glimpses of Ella’s later academic career. In 1890, she was one of 22 students (only 2 from North Acton) who were admitted to the relatively new High School program. She became the managing (and inaugural) editor of the school literary magazine "The Actonian." Ella was one of five students who graduated in June 1894. At the ceremony, she was selected to give an address entitled “Oars and Sails.” Town reports show that Ella L. Miller, while a member of the high school’s senior class, served as an assistant teacher in the South Primary School in Spring 1894. The School Committee’s annual report noted that “during the spring we were obliged, by the large number of pupils in attendance, to employ an assistant teacher and this assistant was compelled to take her classes into a corner of the schoolroom or to the cloak room, or the hallway, as the weather permitted.” (page 56) The hallways presumably would not have been heated. It was certainly an introduction to teaching with constrained resources. Ella and fellow graduate Blanche Varney passed the entrance examination for Framingham Normal School, a teachers’ training college. This was particularly important because as late as the 1897-1898 school year, the Superintendent’s report noted that Acton’s high school was not approved by the State Board of Education. The 1890s were a time when the state and the towns were struggling with what constituted a legitimate high school, with issues such as the minimum number of teachers, years of study, and curriculum. Ella’s autograph book, in possession of the Society, shows that she was originally a member of the Class of 1893, but in 1893, the high school course was changed to four years, and apparently Ella was one of the few who continued on. Ella graduated from Framingham Normal School in 1896. Ella was paid for teaching the North Acton school in the fall and winter of the 1896-1897 school year, taking over after the resignation of Lillian Richardson. Ella taught there for the next two years at a salary of $10 per week. In the Fall of 1899, the North Acton school was merged into the Center school, and Ella started teaching in the new “intermediate” division there (grades 4-6). Probably as a result of her change of school, a typo in the 1900 report said that Ella was “appointed,” starting her service in Acton schools, in 1899. The error was repeated in town reports for decades. On March 17, 1897 (according to Ella’s later diaries), the family moved to Hudson where Charles bought farmland at about 181 Central Street. Charles still owned the North Acton farm, but he was trying to sell it. An ad attached to the back of a photograph owned by the Society reads: “FOR SALE - Thirteen-acre farm: fine vegetable garden: nice lot of sweet corn: asparagus and strawberry beds: good shade trees: excellent drinking water: house six rooms: barn: two henhouses: near railroad station and post office: half mile off State road from Boston to Ayer: two miles to center of town. Desirable for summer home or good location for poultry or small fruit farm. Price $3500. C. I. MILLER, North Acton." Someone wrote on the back of the picture that Charles did not find a buyer. He may have found someone else work the land in the meantime, however. Ella was teaching in North Acton, so we don’t know how she managed logistics. She might have stayed in the house or boarded with a family. Commuting that distance would not have been easy in those days, whether by horse or train. An Acton Center newspaper item in April 1903 mentioned that “Miss Loraine Miller of Hudson spent Monday with her sister, Miss Ella Miller,” giving the impression that Ella was staying in town at least some of the time. Ella’s brother Sam started working for the Boston & Maine Railroad as a telegraph operator and ticket taker in 1899 and moved to Beverly. Ella’s sister Alice married Hudson neighbor Halden L. Coolidge in May 1904 and settled down at 205 Central Street, Hudson. Neither Sam nor Alice lived in Acton after that. We do not know what precipitated Charles’ move to Hudson. His mother, who had remarried and spent many years in Wisconsin, came back to Vermont and passed away in 1895. We had hypothesized that she left him some money. However, Charles entered into various mortgage transactions in the 1900-1904 period, so he may have been feeling financially stretched. The mortgages were paid off. In October 1904, Charles transferred the thirteen-acre North Acton farm to Ella for the price of one dollar. In 1905, a buyer for the Hudson farm materialized, so Ella’s family returned to their North Acton farm late in the year. Ella taught in Acton for eleven years before our diaries begin. Unfortunately, we only have brief snippets from newspapers to show what she was doing aside from teaching during that time. The Enterprise mentioned that Ella taught a Young People’s Society of Christian Endeavor class in early 1896. In January, 1902, she hosted the Shakespeare Club. In August 1907, Ella, Martha Smith, and Sarah and Helen Wood took a vacation at York Beach, Maine (Aug. 14, 1907, p.8) Ella’s parents became involved in the Grange in Hudson. When they were moving back to Acton in late 1905, about one hundred Grange members and neighbors showed up at a sendoff at Alice’s house. Ella and her parents became involved in the formation of the Acton Grange in March 1906. In 1907, Charles and Ella were both elected to Grange positions and Ella’s mother Lizzie was sent to the state Grange meeting as Acton’s delegate. The Grange would continue to be an important part of their lives in later years. Ella’s diaries begin on January 1, 1908. Over the next few months, we plan to use them to learn more about her life and also about what Acton was like in the early years of the twentieth century. The Miller Siblings: Some references used:

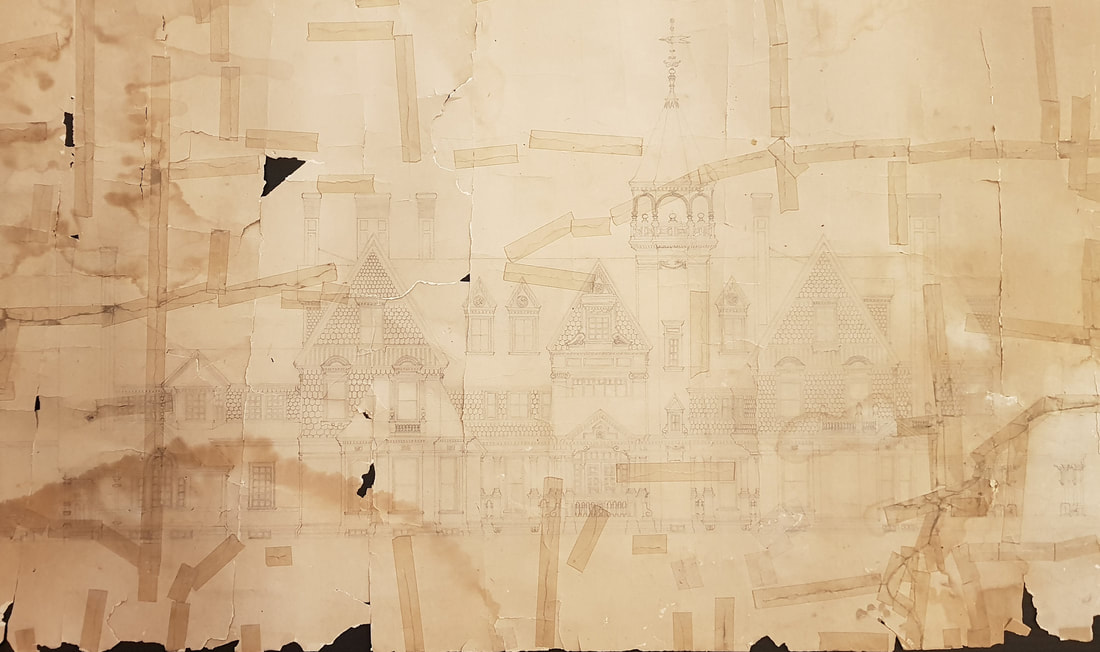

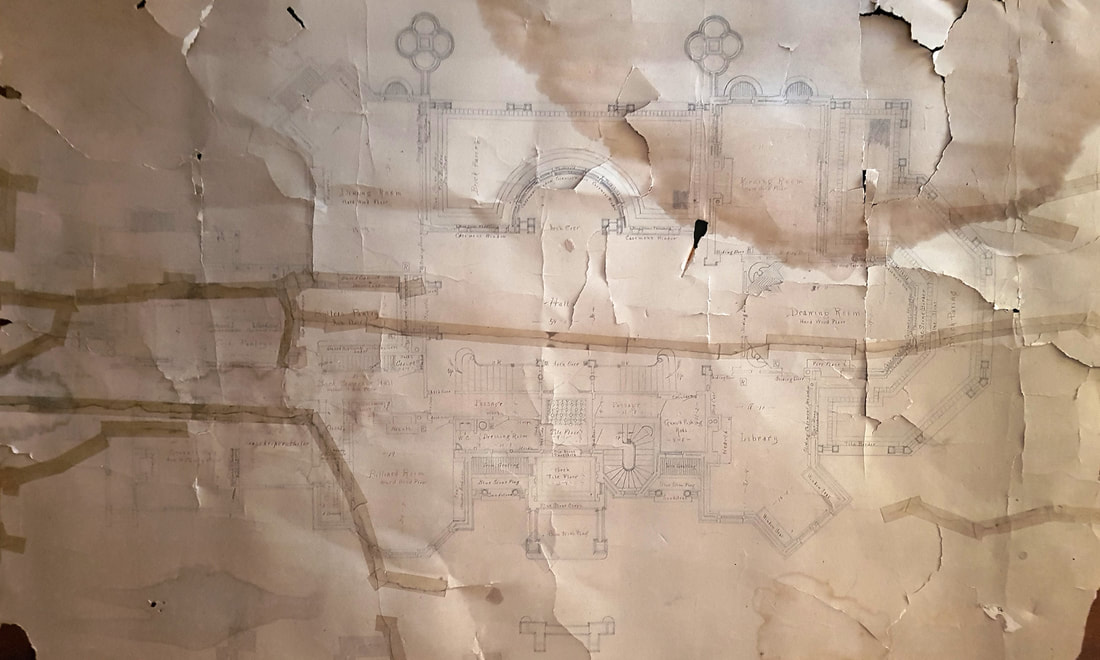

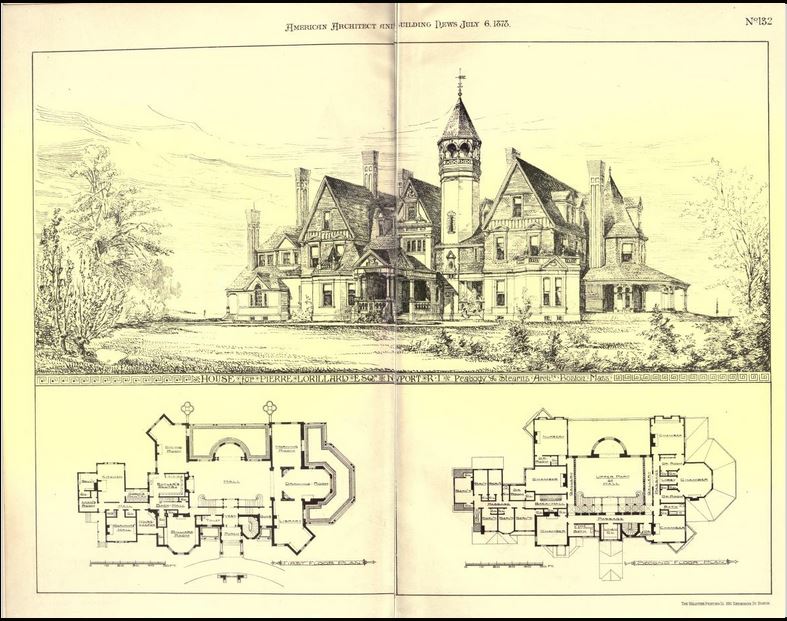

11/19/2021 Newport Under the RaftersRecently, two very large and brittle architectural drawings arrived at Jenks Library. They had been given to our donor decades ago by a West Acton home owner who had found the drawings in the eaves of an outbuilding. Her property had formerly belonged to West Acton builder John S. Hoar, so it was reasonable to assume that the drawings were remnants of one of his projects, hidden away and forgotten for years. When the owner unrolled the paper, it cracked, but what emerged did not look like any Acton property. She taped the torn plans and gave them to a person well-known for his interest in Acton history. He has now shared them with the Society. The plans were undated, unsigned, and gave no indication of whom they were created for. One, a drawing of the exterior of the house, matched none in Acton, and the other’s first-floor details indicated that the owner’s wealth far exceeded that of any of Acton’s early residents. The plan included a hall measuring 54’x 30’, a drawing room (34’ x 19’), morning room (almost 28’ x 12’), library (27’ x ~19’), dining room (31’ x 19’), billiard room (24’ x 19’), kitchen (~25’ x 18’), servants’ hall (20’ x 16’), butler’s pantry, cook’s pantry, housekeeper’s parlor, scullery, “Man’s Room,” and a gun & fishing rod room. Perhaps John S. Hoar had a very wealthy client somewhere, but there was no clue where the house was. Sometime later, our donor was visiting the Breakers in Newport, RI and was inside the Children’s Playhouse on the property. Framed on the wall, he saw a reproduction of a first-floor plan that looked astoundingly like the plan found in West Acton. It came from the first Breakers, built for Pierre Lorillard in 1878 and purchased by Cornelius Vanderbilt in 1885. The building had been designed by prominent Boston architects Peabody & Stearns. The first Breakers burned in November 1892 and the enormous villa designed by Richard Morris Hunt replaced it. All that is left of Peabody & Stearns’ work on the property is the 1886 “Toy house” built by Cornelius Vanderbilt “for the pleasure of his children” soon after they moved in. (Newport Mercury, July 3, 1886, p. 1) Looking at the drawings at Jenks Library, we had a mystery on our hands. Was it truly the first Breakers? If so, what were the plans doing in West Acton? Were these perhaps an architect’s rejects or extra copies for the builder? Was there a connection between the Hoar family and the builder/architects of the original mansion? Had someone given the plans to John S. Hoar simply because he was a builder who would be interested in them? Did he use them as inspiration for his own work? Not confident that we would be able to answer all of those questions, we started with identifying the house. Photos of the first Breakers are available online; despite slight differences, the house pictured looks to be the same as in the drawing. We wanted to compare our first-floor plan to the one used to build the Lorillard Breakers. The book Peabody and Stearns: Country Houses and Seaside Cottages by Annie Robinson has photographs of the house and a reproduction of the first-floor plan which was also featured in The American Architect and Building News, Volume 4, No. 132, July 6, 1878, in an illustrative spread between pages 4 and 5. Our first-floor plan has more details about doors, windows, fireplaces, built-ins, materials, and patterns than the first-floor plan shown on the left, but there is little doubt that the architectural drawings brought into Jenks Library were for the same house. The plans must have been for the original building, because immediately after Cornelius Vanderbilt bought the property, he started renovations. McNeil Brothers, builders from Boston, pulled out mantels and paneling, moved the kitchen away from the main house, and created a new 40’ x 70’ dining room in between, quite different from the original plan. (Newport Mercury, Dec. 4, 1886, p. 1) Our Plan's First-Floor Details. Clockwise from Top Left:

An Unknown Route to the Attic Our next challenge was to try to discover why plans for the long-gone Breakers were found on Windsor Avenue in West Acton in the 1970s. The West Acton building in which the plans were found had belonged to John S. Hoar, son of John Sherman Hoar, Civil War veteran, carpenter, and founder of the New England Vise Company mentioned in previous blog posts. (See original blog post and follow-up.) He came from the Littleton branch of the enormous Hoar family descended from a settler of Concord, MA around 1660. If there was a connection with Newport, it was not because they were a Rhode Island family. Obviously, John S. Hoar did not design the Breakers. Our next hypothesis about the plans was that perhaps he or a relative was involved in building the structure, but our route to proving or disproving that theory was not simple. Though John S. Hoar and his father were involved in building, the father died in 1872 and John S. was only turning 18 in 1878 when the house was being constructed. If he worked in Newport at that time, we have no record of it. Our follow-up theory was that perhaps after the original Breakers was renovated or burned, our drawings, having been superseded, were discarded. After Cornelius Vanderbilt bought the property, the “old” was not of much interest; the Newport Mercury reported that two of the “elegantly carved mantels” were auctioned off for about $100, even then considered much less than they were worth. (Dec. 4, 1886, p. 1) Perhaps someone found the plans, saved them for their historical value, and gave them to John S. Hoar. But who? The West Acton Hoar Family and the Whitney Relatives Our donor believed that other members of John S. Hoar’s family were involved in construction, so we researched uncles and brothers for a connection in Newport. A great deal of searching later, we had only found one promising clue. On Jan. 1, 1892, the Concord Enterprise reported, “Crosby Hoar spent Christmas with his mother. Crosby is superintending the building of some Newport, R. I. residences.” (p. 8) This Crosby Hoar was John S. Hoar’s brother. We thought that we might be able to learn about what Newport residences Crosby worked on and whether he had a connection to the architects Peabody & Stearns, the builder(s) who worked for the Lorillards or Vanderbilts, or anyone else who might logically have had the plans. Following up on Crosby did not easily yield that information, but it was clear that we needed to know more about the extended Hoar family. What follows is a bit of what we learned about the family of John S. Hoar. As mentioned previously, their family roots go way back in the area. It was surprising, therefore, how complicated it was at first to learn about John’s brothers. We will start with their father, the carpenter, farmer, and vise inventor John Sherman Hoar. J. Sherman Hoar, as he preferred to be called, was born in Boxborough on June 19, 1829. J. Sherman’s father John grew up in Littleton, and his mother Betsey Barker grew up in Acton. J. Sherman married Lydia Parker Whitney in 1851 and lived for a few additional years in Boxborough. Around that time, his brother Forestus D. K. Hoar moved to Acton. By the 1860 census, J. Sherman Hoar was living in West Acton with his growing family. Tracking down the family proved challenging until we realized that a number of Sherman and Lydia’s children eventually changed their surnames to Whitney, and one son went by his middle name. As Whitneys appeared in various places, we had to make sure that they were actually originally from the Hoar family and not people of similar names. Trying to answer our questions turned into quite a project. J. Sherman Hoar’s children with Lydia P. Whitney included:

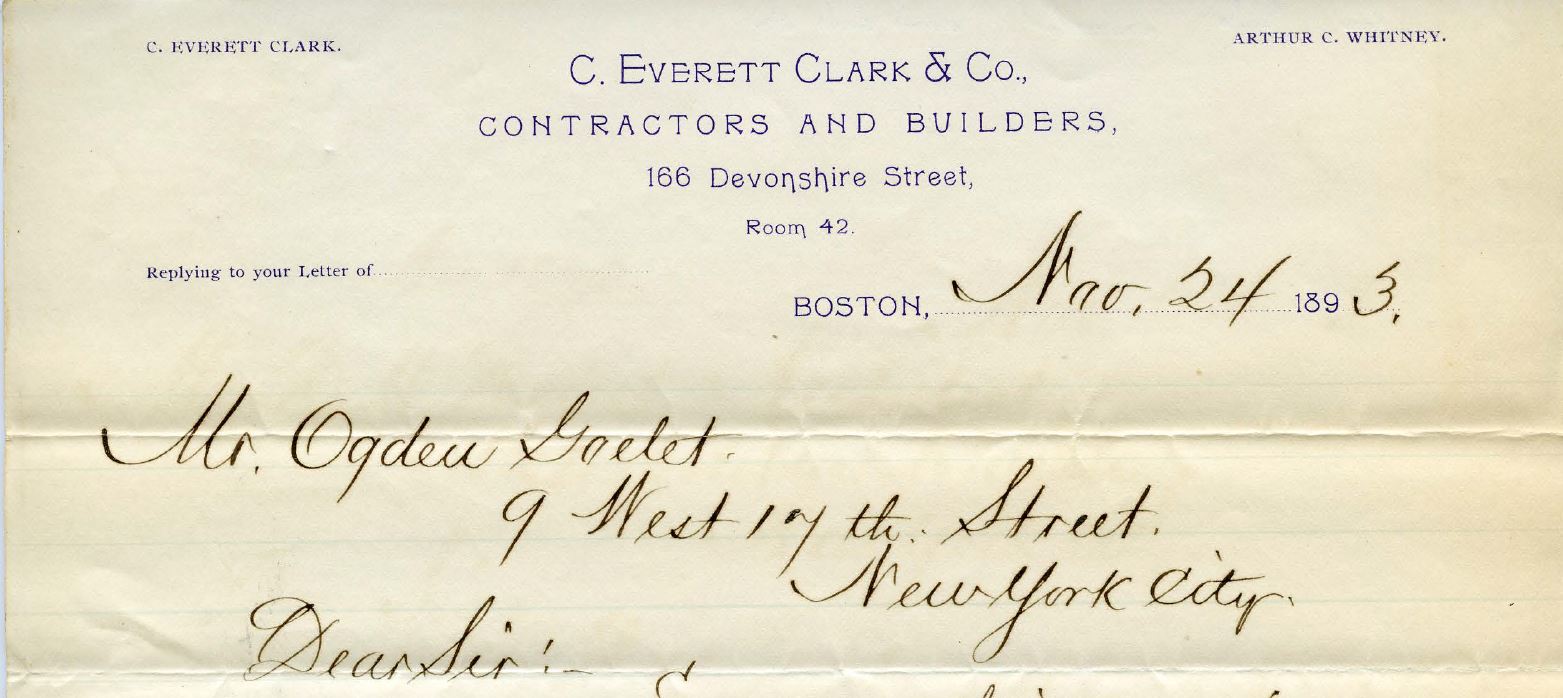

The year 1872 must have been a traumatic time for the family. In June, Sherman’s father John passed away. On October 13, 1872, Sherman died from typhoid fever, and a week later, eldest daughter Kate died from the same disease. The next few years must have brought about a great deal of upheaval. We do not have many details about that time period but have tried to fill in what we could. All of J. Sherman’s sons seem to have worked in construction. According to Lucie Hager’s 1891 Boxborough: A New England Town and Its People, “Three of the sons went West and engaged in business as builders and contractors, and another, John Hoar of West Acton, is an architect.” (p. 158) Following up on that clue, we discovered that the brothers actually headed for the Midwest. Our first round of research, complicated by name changes, showed that the youngest, Edwin Barker [Hoar] Whitney moved to St. Louis, Missouri and stayed there. Census records alternate between showing Edwin as a superintendent employed by a school system and a superintendent working in buildings/construction. He occasionally appears as “Edward.” We will leave that possible confusion for another researcher. Aside from his building connections, we found nothing to indicate that he might have obtained plans to the original Breakers. John S. Hoar’s younger brother Abner Crosby obviously had been involved in construction in Newport. The Newport Directory of 1882 shows a carpenter Crosby Hoar living in a boarding house. Once we realized that he later went by Crosby A. Whitney, we found him in Newport directories in the years 1890-1895, listed explicitly as a builder in the later years. Disappointingly, none of our searches enabled us to find out any more about his time in Newport, including the houses he worked on. By 1896, he had moved to Boston where in April of that year, he married Annie C. Daning. The record lists him as a carpenter. The Boston directory of 1897 shows Crosby A. Whitney as a “building supt. 166 Devonshire, rm. 42.” (More on this later.) Though building superintendent can have different meanings, based on what we have discovered, he would have been a construction supervisor. He apparently spent his career in construction. He was listed as some variation of building superintendent in the 1900-1930 censuses and in Boston directories. His wife Annie died in 1929, and the 1930 census incorrectly listed him as “Crosby A. Fletcher,” living with his sister Alice (Hoar) Fletcher and her husband in Belmont. We did not find online details of his death or burial, although an indexed death record lists a Crosby A. Hoar as having died in Westborough in 1934. Aside from the fact that he was in Newport and in construction, our original research into Crosby did not convince us of a definite connection to the first Newport Breakers. John S. Hoar’s older brother Arthur Cephas became a master builder. Like two of his brothers, he took Whitney as his last name; we found a record of his name change in Massachusetts on Feb. 7, 1881. We knew from Hager’s Boxborough history that he had headed to the Midwest by 1891. A Masonic membership record showed that Arthur C. Hoar Whitney had been associated with the Masons in St. Louis from 1891-1895 (and in Massachusetts before and after). He lived to the age of 97, and his Boston Globe obituary mentioned that he “had designed numerous buildings in Chicago, St. Louis and other Midwest cities” as well as the Groton School chapel. The obituary gave no indication of a Newport connection and was quite vague about his activities before he moved to Lexington (MA) in 1907. (Boston Daily Globe, Nov. 16, 1951, p. 8) Fortunately, we kept looking. Online searching showed that Arthur C. Whitney was in construction in Boston. A digitized 1897 catalogue for a Special Exhibition held by the Boston Architectural Club contained an ad for “C. Everett Clark & Co. Contractors and Builders, 166 Devonshire Street, Room 42, Boston., Mass.” The names at the bottom of the ad were C. Everett Clark and Arthur C. Whitney. We also found an ad in the 1908 Year Book of the Boston Architectural Club showing Arthur C. Whitney, Contractor and Builder, working at 18 Post Office Square in Boston, Room 4. From those two pieces of information, we assumed that Arthur worked with another builder for a short time and then went off on his own. We would have saved time if we had paid more attention to the identity of the partner. However, our research into Arthur C. Whitney’s later life showed that he had a successful career as a builder. By 1899, he was in Milwaukee representing the Boston Master Builders’ Association. (Concord Enterprise, Feb. 2, 1899, p. 8) A 1906 writeup of Arthur C. Whitney in Commercial and Financial New England Illustrated showed that he had worked on numerous big projects in Boston, employed a large number of workers, and “aided materially in carrying out the ideas of some of the most prominent architects in the country.” (p. 264) We did discover that he worked with Peabody & Stearns. Our hypothesis was that someone who worked at Peabody & Stearns or perhaps a Newport builder had discarded our plans and somehow they found their way to Arthur or Crosby Whitney, who then gave them to brother John S. Hoar. The connections still seemed quite tenuous, however. We investigated John S. Hoar last, because we were under the impression that he had stayed in or near West Acton his entire life. When we searched for him in the 1880 census, however, we were surprised to discover that Arthur C. Hoar (age 25) and John S. Hoar (age 20), both carpenters from Massachusetts, were living in a St. Louis, Missouri boarding house. Listed after the brothers was another boarder, a 42-year-old builder from Massachusetts named Charles E. Clark. Following a guess that the Hoar brothers were in St. Louis working for this builder, we belatedly looked into the career of Charles Everett Clark. Finally, a Connection Appears It did not take us long to discover that C. Everett Clark was a well-known Boston builder. An 1895 retrospective of the works of architect Richard Morris Hunt talked at some length about the fact that Hunt had trusted C. Everett Clark to act as general contractor on some of his best-known work, including Newport mansions such as Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Breakers (the second one), Marble House, Belcourt, and the homes of Ogden Goelet (Ochre Court), Professor Shield, and “Mr. Busk” (Joseph R.). Clark also was general contractor for John Jacob Astor’s Fifth Avenue house in New York. The article continued, “We do not speak here of the less notable work which Mr. Clark has done, or even of the many important commissions which he has obtained from other leading architects.” (Architectural Record, Volume V., No. 2, Oct.-Dec. 1895, p. 216) We learned from the Newport Mercury (Sept. 26, 1885, p. 1) that one of those important commissions was the Lorillard (first) Breakers; the contract for the “erection of the elegant villa” was awarded to C. E. Clark of Boston in October, 1877. The connection between the Hoar/Whitney family and the builder of the Lorillard Breakers kept getting stronger. An obituary for Charles Everett Clark was shared on Ancestry.com. (Unfortunately, the only identification was a hand-written “Mar 1899,” but the obituary mentioned that Clark was a “prominent resident of this city,” indicating that the paper must have been published in Somerville, MA.) The article spoke about Clark’s construction company and said that “The Boston office was established about twenty-five years ago, and was placed in charge of Arthur C. Whitney, of Somerville, who acted as superintendent up to five years ago, when he became Mr. Clark’s partner.” C. E. Clark had built hundreds of houses, warehouses, and office buildings, especially in Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, Indianapolis, and St. Paul. He also built “many elegant houses in the Back Bay district of Boston,” the previously mentioned Newport houses, and notable houses in other locations such as Lenox, MA and Canandaigua, NY. Photos Courtesy of Library of Congress At this point, we had discovered that Hoar brother Arthur C. Whitney had worked for C. Everett Clark, builder of both Breakers, since the 1870s. Arthur was a building superintendent and managed the Boston office until he became a partner. His change in status must have happened before November 24, 1893, because letterhead from that date (shared online by Salve Regina University) included his name. Brother Crosby A. Whitney must also have worked for the firm because his work address in the 1897 and 1899 Boston Directories was the same as the Boston office of C. Everett Clark & Co.; Room 42, 166 Devonshire Street. We had previously found evidence that Crosby was living in Newport in 1882 and 1890-1895 and that he was overseeing the building of “some Newport, R. I. residences” in January 1892. Was he involved in building the Vanderbilts’ Breakers, Marble House, or Goelet’s Ochre Court? We do not have proof of that, but we did learn from an 1892 writeup of C. Everett Clark that “He has several superintendents who have been in his employ for nearly twenty years, and who personally superintend his buildings.... he controls his vast business by correspondence with his superintendents and by making regular trips West once a month.” (Boston of Today, A Glance at Its History and Characteristics, ed. Richard Herndon, p. 183) Clearly, one of those superintendents was Arthur C. Whitney. Crosby may have been another. Circling back to youngest [Hoar] brother Edwin Whitney, a building superintendent living in St. Louis, we realized that he also could have been working for C. Everett Clark supervising projects in that city and elsewhere in the Midwest (a theory we did not pursue).

Unfortunately, as time passes, histories of buildings often focus on their architects and do not tend to mention the people involved in the actual construction. The result is that the identities of those who brought the architects’ ideas to fruition can be lost to memory. It was the digitization of contemporaneous reports in newspapers, trade journals, and “Boston of To-day” that allowed us to piece together the connection between the Acton Hoar family and the Lorillard Breakers. Unlikely as it seemed at first, we now know that at least one of the Hoar brothers was working for the builder of the first Breakers at the time it was erected. As partner to that builder in later years, Arthur C. Whitney could easily have had access to the original plans. Questions, of course, remain. Did any of the Hoar brothers actually participate in the building of the Lorillard Breakers in 1877-1878? Were all three “Whitney” brothers building superintendents for C. Everett Clark? Did John S. Hoar work for C. Everett Clark, and if so, for how long? And finally, how exactly did those plans get into John S. Hoar’s workshop attic? If you have any information that will add to this story, we would be delighted to hear from you.

Samuel’s family connections made it highly likely that Samuel also served in the Revolution. Samuel’s brothers Asa and Nathan and many of their relatives served. Samuel also had many soldiers in his family on his wife’s side; she was Lucy Davis, first cousin to Captain Isaac Davis who led the Acton minutemen and fell at Concord’s North Bridge. We checked our standard town histories by Fletcher and Phalen, both of which reprinted Rev. James T. Woodbury’s listing of Actonians who were known (at the time the list was created, sometime in the mid-1800s) to have served in the Revolution. The list is not perfect, and Rev. Woodbury acknowledged at the time that it was incomplete. However, Samuel Parlin did appear in that listing. Some of his children and other relatives living in Acton were the likely sources. Our next challenge was to try to determine when Samuel actually served. Fortunately, our quest was made much easier when we were able to turn to the Robbins papers in our own archives. Not every man who served is listed there either, but for lucky people researching certain individuals, the papers can be a goldmine. It happens that Samuel Parlin was listed as one of the Actonians who signed up on September 29, 1774, “thinking our Selves Ignorant in the Military Art and Willing to be Instructed” by Captain Joseph Robbins in a militia company. Later, Captain Robbins documented the fact that Samuel Parlin had served under him in 1776 (as did his brothers Nathan and Asa). We also discovered that much later, Concord’s Gazette and Yeoman listed those who were living in Acton in April 1824 who had fought at Concord on April 19, 1775. Samuel Parlin was included. (April 24, 1824, p. 2) Having confirmed that Samuel Parlin did indeed serve in the Revolutionary War, we set out to learn about the rest of his life. Samuel was born in Acton on May 18, 1747 to Jonathan Parlin and Sarah Warner. His family were among of the original residents of Acton when it became a town in 1735. They lived in the northern part of Acton (previously Concord) that eventually became Carlisle. A map of historic home sites done by Donald Lapham in 1969 shows that the Jonathan Parlin house was located at 322 West Street (at the corner of Acton Street) in present-day Carlisle. According to The Descendants of Nicholas Parlin, Samuel had numerous siblings, the oldest of whom (Jonathan) died as a soldier in the French and Indian War in 1758. The book lists two brothers (Nathan and Asa) serving in the Revolution and, with some question, an additional soldier brother Nathaniel. Aside from a muster and payroll record indicating that “Nathaniel” Parlin marched from Acton to Roxbury on March 4, 1776 and served six days, we could find no vital or other records for a man of that name. It is very likely that the record was actually Nathan’s. Samuel had a sister Elizabeth who never married, and as the Parlin genealogy added, unhelpfully, “There were four other children, all girls.” (p. 22). We were able to find in Acton’s vital records that Samuel had three additional sisters, Sarah, Lucy, and Mary. Sarah died in 1759. Acton death records do not mention Lucy and Mary, but they must have died before their father, as his probate record does not list them as survivors. (It also does not list a son Nathaniel.) Samuel’s father Jonathan died in 1767. His estate included an 87-acre farm, partly in Acton and partly in Westford, bordering on the land of John Heald Jr. The farm was left 1/3 to Samuel’s mother, as was customary, and 2/3 to the eldest surviving brother Nathan who lived out his life in Carlisle. Asa eventually farmed nearby and served the town of Carlisle for many years as town clerk and selectman. Samuel Parlin, however, moved to a part of town that remained Acton. On March 26, 1772, he married Lucy Davis (1749-1829), daughter of John and Sarah (Flint) Davis of Acton. Samuel and Lucy had eight children:

We know that Samuel Parlin lived at what would now be 48 Hammond Street. The house, which stood until a tragic fire in 1985, was believed to have been built approximately 1772 -1776, presumably based on the date of Samuel’s marriage to Lucy Davis. Supporting that estimate, we found that in the tax valuation of 1771, Samuel was listed without taxable property, but in Lucy’s father’s 1778 probate record, Samuel Parlin was already a landowner. Lucy inherited eight acres of pasture and woodland, known as part of the “Proctor Place” that bordered land of “Samuel Parling.” The probate record also noted that Lucy’s father had previously given her 86 pounds, 19 shillings and 9 pence, probably the value of land John gave to Lucy and Samuel as they started their life together. Lucy inherited an additional thirty-acre lot on the “westerly side of Nagog Hill” when her eldest brother John died in an accident on March 2, 1791. The lot was bounded by land that had been set off to her sister Abigail Conant and by land of Simon Tuttle and Samuel Jones Jr. Samuel first appears in Acton’s town meeting records as a fence viewer in 1776. He was clearly back from military service in 1780 because he was chosen selectman and assessor in that year. Starting in 1783, he was chosen regularly for roles such as constable, tithing man, assessor, surveyor of timbers or highways, and school committee. He was also selected as a member of special committees, for example to deal with abatements to individuals’ taxes and to deal with the selectmen about town expenditures. He was made a member of the committee to instruct the Convention at Concord in Oct. 1786 (probably the Middlesex County convention dealing with issues that led to Shay’s Rebellion). In May 1798, town meeting records show that he was selected for a special committee “In a Constitutional mannar to take under Consideration the alarming Situation of our publick affairs and express there minds thereon the Town Expressed there minds agreeable to this article and Chose Jonas Brooks John Edwards Jonas Heald Samuel Parling and Thomas Noys a Committee to publish the Same.” (This was probably related to tricky diplomatic issues with France.) It is clear that Samuel Parlin was a trusted figure in town, someone who could handle both money and negotiations amid controversy. According to church records, on Nov. 24, 1791, Samuel Parlin was chosen for the office of Deacon of the First Parish church of Acton. On April 19, 1792, the record continued that Samuel Parlin having declined, the church chose Simon Hunt who accepted and “took the seat” in August. While the Parlin genealogy refers to him as “Deacon Samuel,” there is no record that Samuel Parlin actually ever “took the seat” himself. The story of why he declined the honor never made it to the history books.  Samuel Parlin died on March 7, 1827, leaving his widow Lucy and four surviving children. At the time of his death, his real estate included the home farm containing 38 acres of land, a 5-acre “Sargent Meadow”, a 6-acre “Chaffin Meadow”, and an 11-acre “Littleton Pasture.” He also had the title to pew number 42 on the lower floor of the Acton Meeting house. Among his personal belongings were agricultural products and tools, cows, swine, sheep, and, oddly, ½ of a horse. Samuel’s widow Lucy survived him by two years, and eldest son Jonathan only by three. The home farm passed to son Davis in 1831. The house eventually went out of the family to Thomas Hammond whose name was given to the road on which they lived. When some of the land was developed in the late 1960s, the new road was given the name of Samuel Parlin Drive. Our research into Samuel Parlin reminded us of a few lessons that are worth repeating. Despite having found what looked like a very complete genealogy of the Parlin family, if we had not checked each item, we would have believed that Samuel had an additional brother named Nathaniel and that Samuel’s son Samuel Jr. lived to adulthood and married a woman named Phoebe. If we had only paid attention to the flag holder in Woodlawn Cemetery, we would have thought that Samuel’s military service was in the War of 1812, not the Revolution. And if we had stopped our searching at Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, we would have missed Samuel’s service, the best documentation of which, ironically, is in our own archives. Some Sources Consulted:

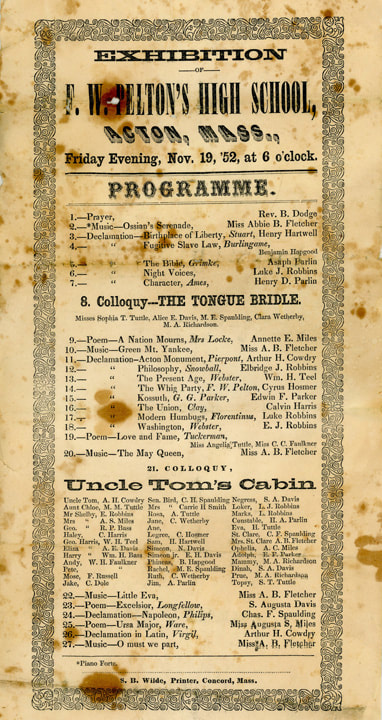

In the years before Acton had a high school of its own, students wanting to further their education needed to take opportunities where they could be found. In Acton’s early days, young men were usually the ones to seek education beyond the schoolhouse; they might be given advanced training or prepared for college by a learned individual, often the town’s minister. In the 1800s, more opportunities arose for young men and young women; some might board at private academies or, as time went on, commute to a nearby high school. In the early 1850s, Acton’s advanced students had the option of studying for short periods at a privately-run advanced school. Our Society’s collection includes a program for an exhibition of F. W. Pelton’s High School in the center district of Acton, starting at 6 p.m. on November 19, 1852. It must have been a long evening; there were twenty-seven items on the agenda, including two dramatic pieces. The Exhibition As evidence of what was going on in the minds of young Actonians in 1852, the “programme” is a revealing document. Even in a small town, there was obvious interest in the issues affecting the country as a whole. Abolition was the foremost theme of the evening. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, though now criticized because of its racial stereotypes, was hugely influential in raising awareness of the evils of slavery. It had been serialized starting in June 1851 but had only been out in book form since March 1852. An early performance in Acton, featuring over 30 performers, would have been a notable event. The song “Little Eva” that followed the performance was based on the book and had recently been published in Boston. Other items on the program that involved the issue of slavery were “declamations” on Anson Burlingame’s opposition to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, Grimke’s “Bible”, presumably Angelina Grimke’s “Appeal to the Christian Women of the South” (1836), and Henry Clay’s attempts to save “The Union” without war. Other declamations had as their subjects Daniel Webster’s writings on Washington and on “The Present Age,” Lajos Kossuth, a Hungarian leader whose words had managed to catch the popular imagination in the United States, Napoleon, and the Whig Party (written by the schoolmaster himself). We were not able to identify all of the items performed. Ames’ “Character” may have referred to one of Fisher Ames’ writings, but there is not enough information to be sure. Stuart’s “Birthplace of Liberty” and Snowball’s philosophy were similarly hard to pin down. In online searching, some of the titles are now overshadowed by later writings and events. A search for Snowball’s “Philosophy” led to many references to George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Searching for “A Nation Mourns” brought up references to Lincoln’s assassination, and “Modern Humbugs” yielded P. T. Barnum’s book The Humbugs of the World, both dating from the 1860s. (“Modern Humbugs” by Florentinus may have been a tongue-in-cheek piece written by the schoolmaster; see the section on him below.) Drama, songs, and poetry were easier to find. “The Tongue Bridle” was a dramatic piece for “four older girls” published in Boston in 1851. Thanks to the Library of Congress’ Music Division, we were able to find the 1849 Ossian’s Serenade, the 1851 Oh, Must We Part to Meet No More?, and The Green Mt. Yankee, a Temperance Medley, published in Boston in 1852. Once we had navigated past references to Led Zepplin songs, we were able to find an 1848 song by I. B. Woodbury that set Tennyson’s poem "The May Queen" to music. Henry Theodore Tuckerman’s “Love and Fame,” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1841 “Excelsior,” and Henry Ware, Jr.’s “To the Ursa Major” can all be found in online poetry collections. The only item with a strictly Acton theme was Pierpont’s poem “Acton Monument.” One wonders if the entire poem describing the events of April 18-19, 1775 was recited; even at its debut, the audience became impatient with its length. Rev. John Pierpont of Medford presented the poem at the celebration of the completion of Acton’s Monument in 1851. The reverend had the misfortune that day of being slated to recite after an hour-long address by Governor George S. Boutwell and just before the meal was served. Hungry attendees started eating during his recital of the poem, and the clatter of utensils clashed with the sound of the reverend’s voice. Apparently, he got quite upset. Acton’s Rev. Woodbury, who could have tried to quiet the crowd, instead said a quick grace and let the dinner officially begin. Boutwell’s Reminiscences quote Woodbury as telling the poet, “They listened very well, ‘till you got to Greece. They didn’t care anything about Greece.” (page 130) By that point in the day’s speeches, the audience might have been losing enthusiasm for Acton as well. Later, obviously having calmed down, Rev. Pierpont commented on the situation that “Poets at dinners must learn to be brief, Or their tongues will be beaten by cold tongue of beef.” [Boston Evening Transcript, Oct. 30, 1851, p.1) The audience at Pelton’s High School Exhibition had to have been tired by the end of the evening. After speeches, songs, poetry, and drama, Arthur Cowdrey capped off the event with a declamation in Latin from Virgil. Presumably this was to wow the audience. (Clearly, Mr. Pelton was able to teach his students a range of subjects.) Miss A. B. Fletcher performed her fourth musical number, and the evening was finished. Acton’s Private High Schools