|

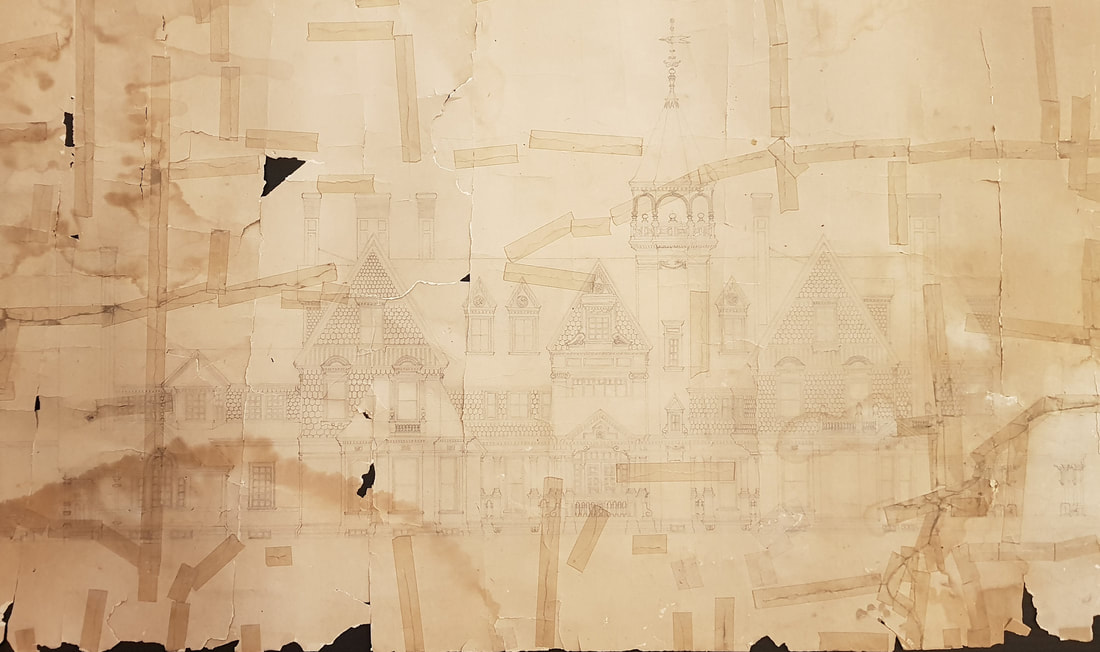

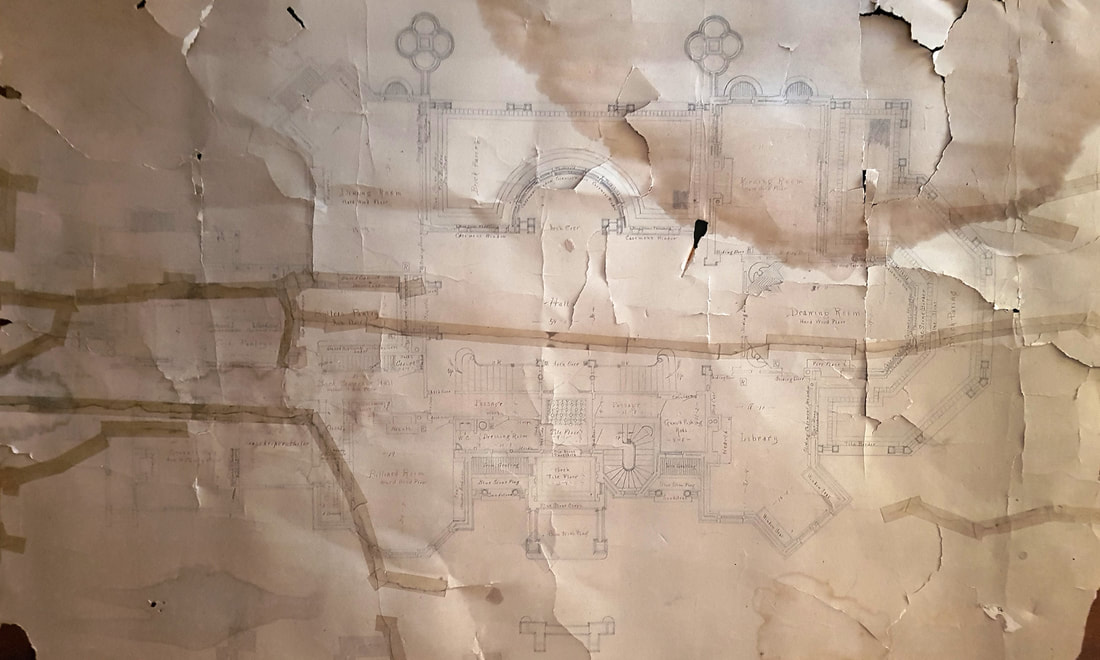

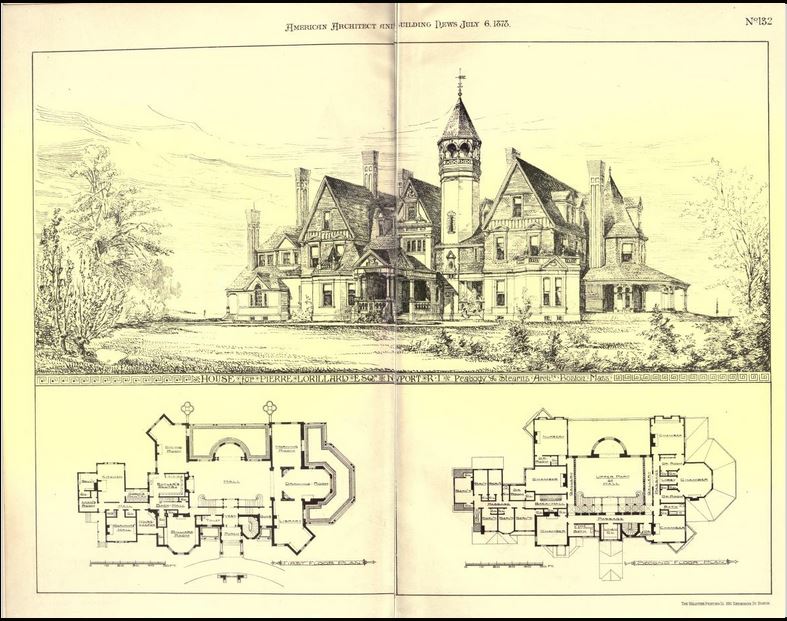

11/19/2021 Newport Under the RaftersRecently, two very large and brittle architectural drawings arrived at Jenks Library. They had been given to our donor decades ago by a West Acton home owner who had found the drawings in the eaves of an outbuilding. Her property had formerly belonged to West Acton builder John S. Hoar, so it was reasonable to assume that the drawings were remnants of one of his projects, hidden away and forgotten for years. When the owner unrolled the paper, it cracked, but what emerged did not look like any Acton property. She taped the torn plans and gave them to a person well-known for his interest in Acton history. He has now shared them with the Society. The plans were undated, unsigned, and gave no indication of whom they were created for. One, a drawing of the exterior of the house, matched none in Acton, and the other’s first-floor details indicated that the owner’s wealth far exceeded that of any of Acton’s early residents. The plan included a hall measuring 54’x 30’, a drawing room (34’ x 19’), morning room (almost 28’ x 12’), library (27’ x ~19’), dining room (31’ x 19’), billiard room (24’ x 19’), kitchen (~25’ x 18’), servants’ hall (20’ x 16’), butler’s pantry, cook’s pantry, housekeeper’s parlor, scullery, “Man’s Room,” and a gun & fishing rod room. Perhaps John S. Hoar had a very wealthy client somewhere, but there was no clue where the house was. Sometime later, our donor was visiting the Breakers in Newport, RI and was inside the Children’s Playhouse on the property. Framed on the wall, he saw a reproduction of a first-floor plan that looked astoundingly like the plan found in West Acton. It came from the first Breakers, built for Pierre Lorillard in 1878 and purchased by Cornelius Vanderbilt in 1885. The building had been designed by prominent Boston architects Peabody & Stearns. The first Breakers burned in November 1892 and the enormous villa designed by Richard Morris Hunt replaced it. All that is left of Peabody & Stearns’ work on the property is the 1886 “Toy house” built by Cornelius Vanderbilt “for the pleasure of his children” soon after they moved in. (Newport Mercury, July 3, 1886, p. 1) Looking at the drawings at Jenks Library, we had a mystery on our hands. Was it truly the first Breakers? If so, what were the plans doing in West Acton? Were these perhaps an architect’s rejects or extra copies for the builder? Was there a connection between the Hoar family and the builder/architects of the original mansion? Had someone given the plans to John S. Hoar simply because he was a builder who would be interested in them? Did he use them as inspiration for his own work? Not confident that we would be able to answer all of those questions, we started with identifying the house. Photos of the first Breakers are available online; despite slight differences, the house pictured looks to be the same as in the drawing. We wanted to compare our first-floor plan to the one used to build the Lorillard Breakers. The book Peabody and Stearns: Country Houses and Seaside Cottages by Annie Robinson has photographs of the house and a reproduction of the first-floor plan which was also featured in The American Architect and Building News, Volume 4, No. 132, July 6, 1878, in an illustrative spread between pages 4 and 5. Our first-floor plan has more details about doors, windows, fireplaces, built-ins, materials, and patterns than the first-floor plan shown on the left, but there is little doubt that the architectural drawings brought into Jenks Library were for the same house. The plans must have been for the original building, because immediately after Cornelius Vanderbilt bought the property, he started renovations. McNeil Brothers, builders from Boston, pulled out mantels and paneling, moved the kitchen away from the main house, and created a new 40’ x 70’ dining room in between, quite different from the original plan. (Newport Mercury, Dec. 4, 1886, p. 1) Our Plan's First-Floor Details. Clockwise from Top Left:

An Unknown Route to the Attic Our next challenge was to try to discover why plans for the long-gone Breakers were found on Windsor Avenue in West Acton in the 1970s. The West Acton building in which the plans were found had belonged to John S. Hoar, son of John Sherman Hoar, Civil War veteran, carpenter, and founder of the New England Vise Company mentioned in previous blog posts. (See original blog post and follow-up.) He came from the Littleton branch of the enormous Hoar family descended from a settler of Concord, MA around 1660. If there was a connection with Newport, it was not because they were a Rhode Island family. Obviously, John S. Hoar did not design the Breakers. Our next hypothesis about the plans was that perhaps he or a relative was involved in building the structure, but our route to proving or disproving that theory was not simple. Though John S. Hoar and his father were involved in building, the father died in 1872 and John S. was only turning 18 in 1878 when the house was being constructed. If he worked in Newport at that time, we have no record of it. Our follow-up theory was that perhaps after the original Breakers was renovated or burned, our drawings, having been superseded, were discarded. After Cornelius Vanderbilt bought the property, the “old” was not of much interest; the Newport Mercury reported that two of the “elegantly carved mantels” were auctioned off for about $100, even then considered much less than they were worth. (Dec. 4, 1886, p. 1) Perhaps someone found the plans, saved them for their historical value, and gave them to John S. Hoar. But who? The West Acton Hoar Family and the Whitney Relatives Our donor believed that other members of John S. Hoar’s family were involved in construction, so we researched uncles and brothers for a connection in Newport. A great deal of searching later, we had only found one promising clue. On Jan. 1, 1892, the Concord Enterprise reported, “Crosby Hoar spent Christmas with his mother. Crosby is superintending the building of some Newport, R. I. residences.” (p. 8) This Crosby Hoar was John S. Hoar’s brother. We thought that we might be able to learn about what Newport residences Crosby worked on and whether he had a connection to the architects Peabody & Stearns, the builder(s) who worked for the Lorillards or Vanderbilts, or anyone else who might logically have had the plans. Following up on Crosby did not easily yield that information, but it was clear that we needed to know more about the extended Hoar family. What follows is a bit of what we learned about the family of John S. Hoar. As mentioned previously, their family roots go way back in the area. It was surprising, therefore, how complicated it was at first to learn about John’s brothers. We will start with their father, the carpenter, farmer, and vise inventor John Sherman Hoar. J. Sherman Hoar, as he preferred to be called, was born in Boxborough on June 19, 1829. J. Sherman’s father John grew up in Littleton, and his mother Betsey Barker grew up in Acton. J. Sherman married Lydia Parker Whitney in 1851 and lived for a few additional years in Boxborough. Around that time, his brother Forestus D. K. Hoar moved to Acton. By the 1860 census, J. Sherman Hoar was living in West Acton with his growing family. Tracking down the family proved challenging until we realized that a number of Sherman and Lydia’s children eventually changed their surnames to Whitney, and one son went by his middle name. As Whitneys appeared in various places, we had to make sure that they were actually originally from the Hoar family and not people of similar names. Trying to answer our questions turned into quite a project. J. Sherman Hoar’s children with Lydia P. Whitney included:

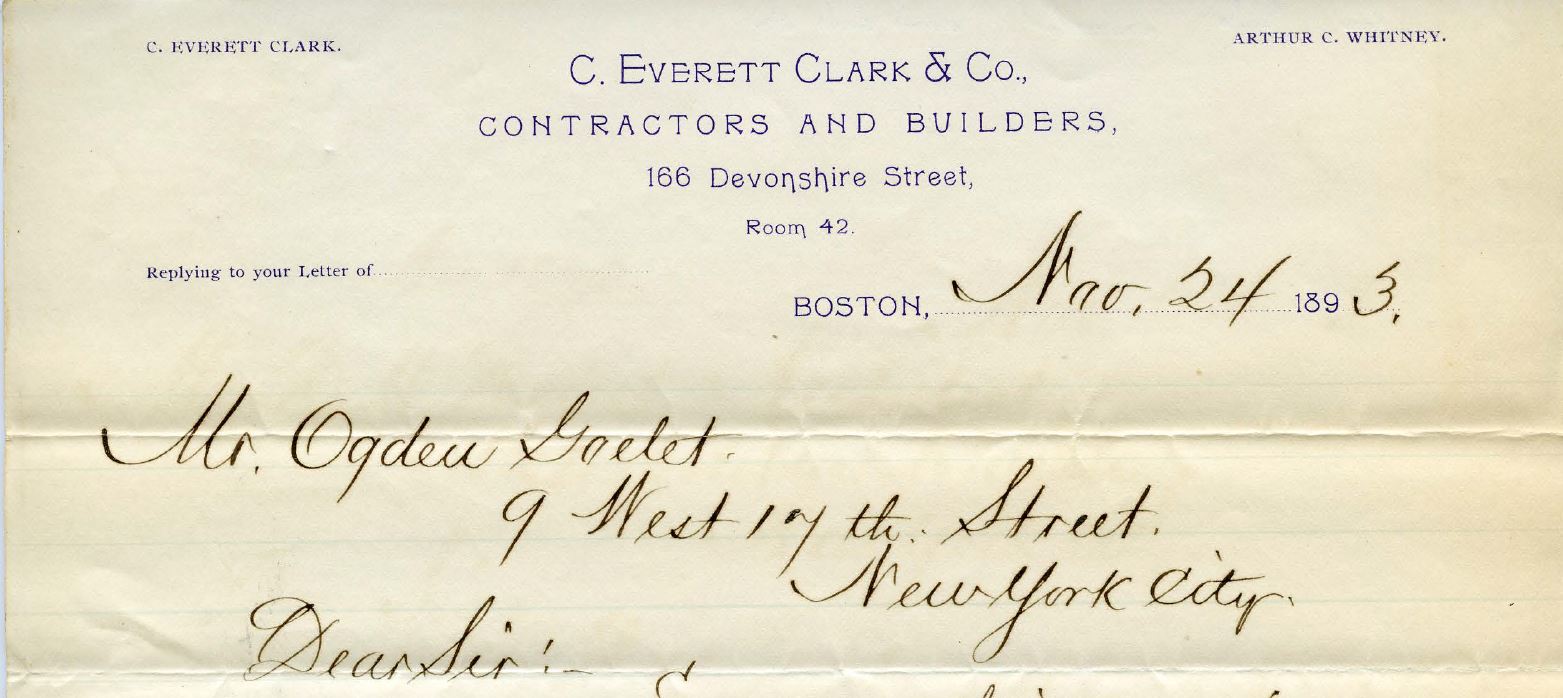

The year 1872 must have been a traumatic time for the family. In June, Sherman’s father John passed away. On October 13, 1872, Sherman died from typhoid fever, and a week later, eldest daughter Kate died from the same disease. The next few years must have brought about a great deal of upheaval. We do not have many details about that time period but have tried to fill in what we could. All of J. Sherman’s sons seem to have worked in construction. According to Lucie Hager’s 1891 Boxborough: A New England Town and Its People, “Three of the sons went West and engaged in business as builders and contractors, and another, John Hoar of West Acton, is an architect.” (p. 158) Following up on that clue, we discovered that the brothers actually headed for the Midwest. Our first round of research, complicated by name changes, showed that the youngest, Edwin Barker [Hoar] Whitney moved to St. Louis, Missouri and stayed there. Census records alternate between showing Edwin as a superintendent employed by a school system and a superintendent working in buildings/construction. He occasionally appears as “Edward.” We will leave that possible confusion for another researcher. Aside from his building connections, we found nothing to indicate that he might have obtained plans to the original Breakers. John S. Hoar’s younger brother Abner Crosby obviously had been involved in construction in Newport. The Newport Directory of 1882 shows a carpenter Crosby Hoar living in a boarding house. Once we realized that he later went by Crosby A. Whitney, we found him in Newport directories in the years 1890-1895, listed explicitly as a builder in the later years. Disappointingly, none of our searches enabled us to find out any more about his time in Newport, including the houses he worked on. By 1896, he had moved to Boston where in April of that year, he married Annie C. Daning. The record lists him as a carpenter. The Boston directory of 1897 shows Crosby A. Whitney as a “building supt. 166 Devonshire, rm. 42.” (More on this later.) Though building superintendent can have different meanings, based on what we have discovered, he would have been a construction supervisor. He apparently spent his career in construction. He was listed as some variation of building superintendent in the 1900-1930 censuses and in Boston directories. His wife Annie died in 1929, and the 1930 census incorrectly listed him as “Crosby A. Fletcher,” living with his sister Alice (Hoar) Fletcher and her husband in Belmont. We did not find online details of his death or burial, although an indexed death record lists a Crosby A. Hoar as having died in Westborough in 1934. Aside from the fact that he was in Newport and in construction, our original research into Crosby did not convince us of a definite connection to the first Newport Breakers. John S. Hoar’s older brother Arthur Cephas became a master builder. Like two of his brothers, he took Whitney as his last name; we found a record of his name change in Massachusetts on Feb. 7, 1881. We knew from Hager’s Boxborough history that he had headed to the Midwest by 1891. A Masonic membership record showed that Arthur C. Hoar Whitney had been associated with the Masons in St. Louis from 1891-1895 (and in Massachusetts before and after). He lived to the age of 97, and his Boston Globe obituary mentioned that he “had designed numerous buildings in Chicago, St. Louis and other Midwest cities” as well as the Groton School chapel. The obituary gave no indication of a Newport connection and was quite vague about his activities before he moved to Lexington (MA) in 1907. (Boston Daily Globe, Nov. 16, 1951, p. 8) Fortunately, we kept looking. Online searching showed that Arthur C. Whitney was in construction in Boston. A digitized 1897 catalogue for a Special Exhibition held by the Boston Architectural Club contained an ad for “C. Everett Clark & Co. Contractors and Builders, 166 Devonshire Street, Room 42, Boston., Mass.” The names at the bottom of the ad were C. Everett Clark and Arthur C. Whitney. We also found an ad in the 1908 Year Book of the Boston Architectural Club showing Arthur C. Whitney, Contractor and Builder, working at 18 Post Office Square in Boston, Room 4. From those two pieces of information, we assumed that Arthur worked with another builder for a short time and then went off on his own. We would have saved time if we had paid more attention to the identity of the partner. However, our research into Arthur C. Whitney’s later life showed that he had a successful career as a builder. By 1899, he was in Milwaukee representing the Boston Master Builders’ Association. (Concord Enterprise, Feb. 2, 1899, p. 8) A 1906 writeup of Arthur C. Whitney in Commercial and Financial New England Illustrated showed that he had worked on numerous big projects in Boston, employed a large number of workers, and “aided materially in carrying out the ideas of some of the most prominent architects in the country.” (p. 264) We did discover that he worked with Peabody & Stearns. Our hypothesis was that someone who worked at Peabody & Stearns or perhaps a Newport builder had discarded our plans and somehow they found their way to Arthur or Crosby Whitney, who then gave them to brother John S. Hoar. The connections still seemed quite tenuous, however. We investigated John S. Hoar last, because we were under the impression that he had stayed in or near West Acton his entire life. When we searched for him in the 1880 census, however, we were surprised to discover that Arthur C. Hoar (age 25) and John S. Hoar (age 20), both carpenters from Massachusetts, were living in a St. Louis, Missouri boarding house. Listed after the brothers was another boarder, a 42-year-old builder from Massachusetts named Charles E. Clark. Following a guess that the Hoar brothers were in St. Louis working for this builder, we belatedly looked into the career of Charles Everett Clark. Finally, a Connection Appears It did not take us long to discover that C. Everett Clark was a well-known Boston builder. An 1895 retrospective of the works of architect Richard Morris Hunt talked at some length about the fact that Hunt had trusted C. Everett Clark to act as general contractor on some of his best-known work, including Newport mansions such as Cornelius Vanderbilt’s Breakers (the second one), Marble House, Belcourt, and the homes of Ogden Goelet (Ochre Court), Professor Shield, and “Mr. Busk” (Joseph R.). Clark also was general contractor for John Jacob Astor’s Fifth Avenue house in New York. The article continued, “We do not speak here of the less notable work which Mr. Clark has done, or even of the many important commissions which he has obtained from other leading architects.” (Architectural Record, Volume V., No. 2, Oct.-Dec. 1895, p. 216) We learned from the Newport Mercury (Sept. 26, 1885, p. 1) that one of those important commissions was the Lorillard (first) Breakers; the contract for the “erection of the elegant villa” was awarded to C. E. Clark of Boston in October, 1877. The connection between the Hoar/Whitney family and the builder of the Lorillard Breakers kept getting stronger. An obituary for Charles Everett Clark was shared on Ancestry.com. (Unfortunately, the only identification was a hand-written “Mar 1899,” but the obituary mentioned that Clark was a “prominent resident of this city,” indicating that the paper must have been published in Somerville, MA.) The article spoke about Clark’s construction company and said that “The Boston office was established about twenty-five years ago, and was placed in charge of Arthur C. Whitney, of Somerville, who acted as superintendent up to five years ago, when he became Mr. Clark’s partner.” C. E. Clark had built hundreds of houses, warehouses, and office buildings, especially in Chicago, St. Louis, Kansas City, Indianapolis, and St. Paul. He also built “many elegant houses in the Back Bay district of Boston,” the previously mentioned Newport houses, and notable houses in other locations such as Lenox, MA and Canandaigua, NY. Photos Courtesy of Library of Congress At this point, we had discovered that Hoar brother Arthur C. Whitney had worked for C. Everett Clark, builder of both Breakers, since the 1870s. Arthur was a building superintendent and managed the Boston office until he became a partner. His change in status must have happened before November 24, 1893, because letterhead from that date (shared online by Salve Regina University) included his name. Brother Crosby A. Whitney must also have worked for the firm because his work address in the 1897 and 1899 Boston Directories was the same as the Boston office of C. Everett Clark & Co.; Room 42, 166 Devonshire Street. We had previously found evidence that Crosby was living in Newport in 1882 and 1890-1895 and that he was overseeing the building of “some Newport, R. I. residences” in January 1892. Was he involved in building the Vanderbilts’ Breakers, Marble House, or Goelet’s Ochre Court? We do not have proof of that, but we did learn from an 1892 writeup of C. Everett Clark that “He has several superintendents who have been in his employ for nearly twenty years, and who personally superintend his buildings.... he controls his vast business by correspondence with his superintendents and by making regular trips West once a month.” (Boston of Today, A Glance at Its History and Characteristics, ed. Richard Herndon, p. 183) Clearly, one of those superintendents was Arthur C. Whitney. Crosby may have been another. Circling back to youngest [Hoar] brother Edwin Whitney, a building superintendent living in St. Louis, we realized that he also could have been working for C. Everett Clark supervising projects in that city and elsewhere in the Midwest (a theory we did not pursue).

Unfortunately, as time passes, histories of buildings often focus on their architects and do not tend to mention the people involved in the actual construction. The result is that the identities of those who brought the architects’ ideas to fruition can be lost to memory. It was the digitization of contemporaneous reports in newspapers, trade journals, and “Boston of To-day” that allowed us to piece together the connection between the Acton Hoar family and the Lorillard Breakers. Unlikely as it seemed at first, we now know that at least one of the Hoar brothers was working for the builder of the first Breakers at the time it was erected. As partner to that builder in later years, Arthur C. Whitney could easily have had access to the original plans. Questions, of course, remain. Did any of the Hoar brothers actually participate in the building of the Lorillard Breakers in 1877-1878? Were all three “Whitney” brothers building superintendents for C. Everett Clark? Did John S. Hoar work for C. Everett Clark, and if so, for how long? And finally, how exactly did those plans get into John S. Hoar’s workshop attic? If you have any information that will add to this story, we would be delighted to hear from you. Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed