|

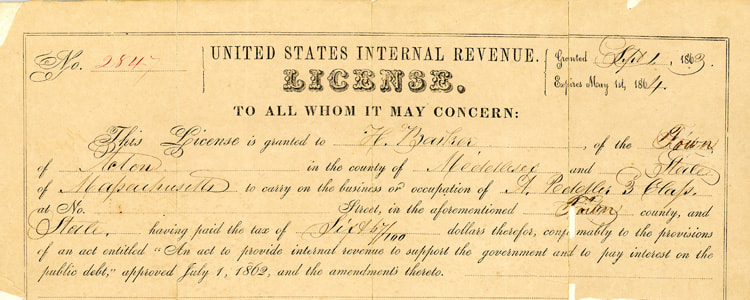

11/25/2023 Two Enterprising EbenezersAfter over two centuries of ownership by the Davis family, Acton’s Ebenezer Davis, Jr. farm was sold in 1968. In an outbuilding locally known as “the Bellows Shop,” an astounding collection of documents, photos, and artifacts was discovered. Some of these items have now been donated to the Society, while others have found their way to the Concord Museum. These donations led us to research economic activities and business relationships in the Davis’ corner of East Acton during the first half of the 19th century. A number of Actonians left during that period to pursue economic opportunities elsewhere. Some, however, put their imaginations and energies to work on ventures in their hometown. Two such enterprising individuals were Ebenezer Davis Sr. and Jr. There have been several Davis families who contributed to Acton’s history. The story of the Ebenezers’ Davis family in Acton began with the 1738 purchase by Gershom Davis (also known as Davies) of about 664 acres in the northern part of Acton, including a house, barn, grist mill, and saw mill that had belonged to Thomas Wheeler. Over time, the land was divided among descendants who proceeded to sell, buy, and mortgage various pieces of the property. It can be bewildering to try to trace each person’s holdings. What we do know, however, is that Gershom’s great-grandson Ebenezer Davis Sr. (1777-1851) lived and farmed at approximately today’s 42 Davis Road on a site that was later Griffin’s Bellows Stock Farm and then Dropkick Murphy’s Sanatorium. Though the house no longer stands, part of its large chimney remains on the property, as well as a former barn (probably later than Ebenezer’s day) that has been converted to other uses. Ebenezer Davis Sr. was apparently a busy man. Deeds refer to him as a wheelwright (from 1800 to 1810, 1815), a yeoman (farmer, 1815, 1819 and later) and a housewright (1807-1808, 1817-1818). The Concord Museum now owns and has digitized ledgers belonging to Ebenezer Davis Sr. and his son Ebenezer Jr. from 1815 through 1853 (unfortunately with certain years missing). Though not complete, the ledgers show the variety of enterprises that Ebenezer Sr. was involved in. As deed research indicated, an early business of Ebenezer Sr. was blacksmithing and wheelwrighting. His ledger makes for somewhat confusing reading, because his thrifty reuse of pages means that the top of a page may relate to his early business and the bottom may contain notations from a decade or more later. However, the ledger does show over thirty customers in the 1815-1816 period who paid for jobs such as

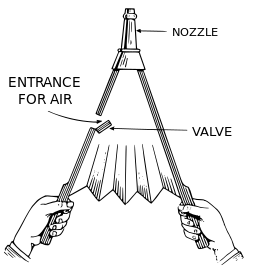

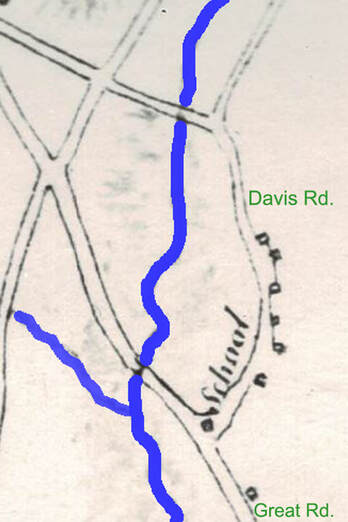

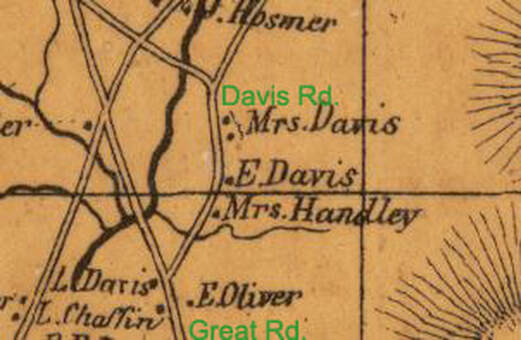

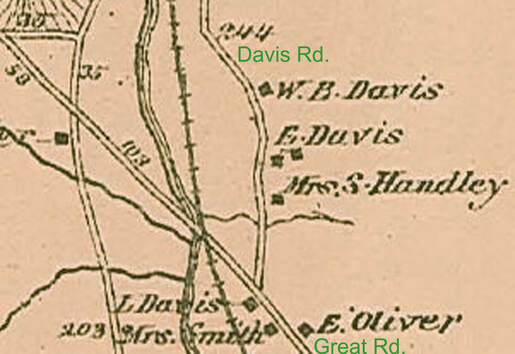

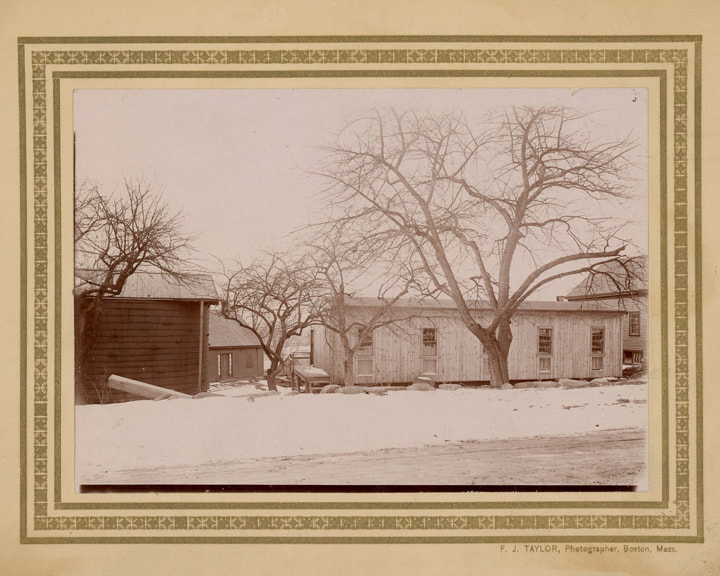

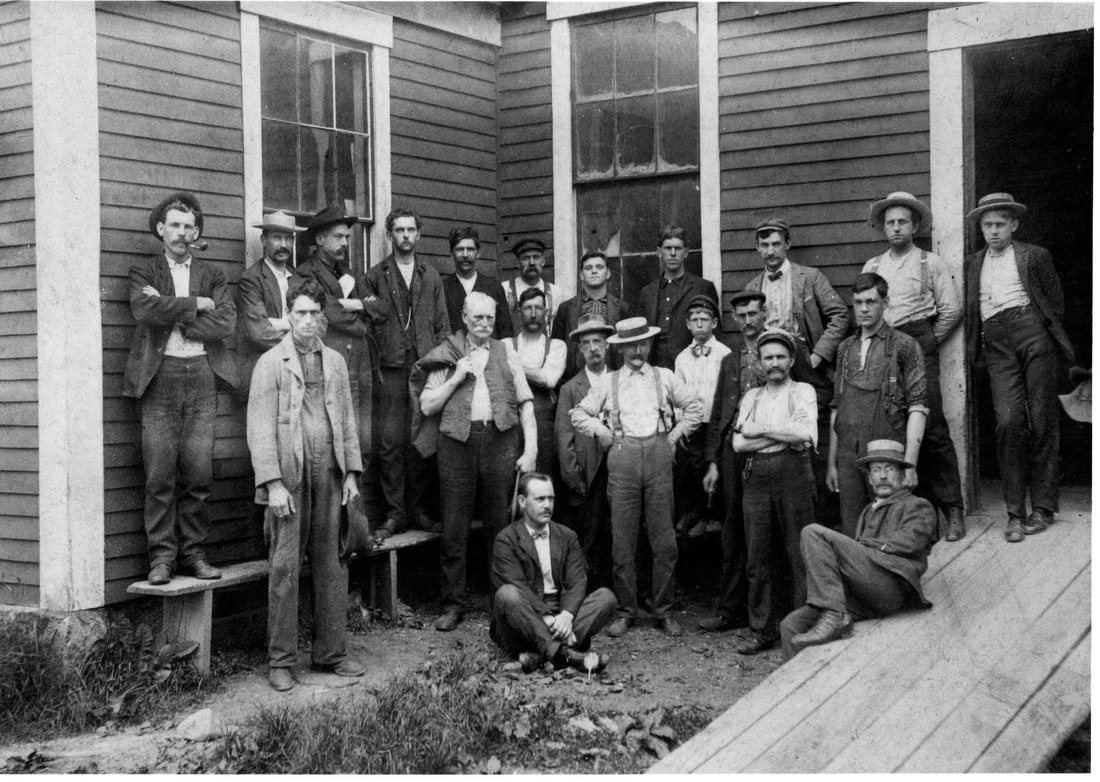

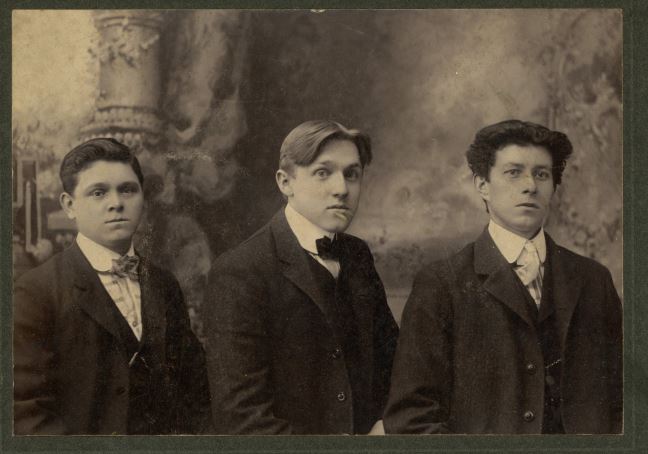

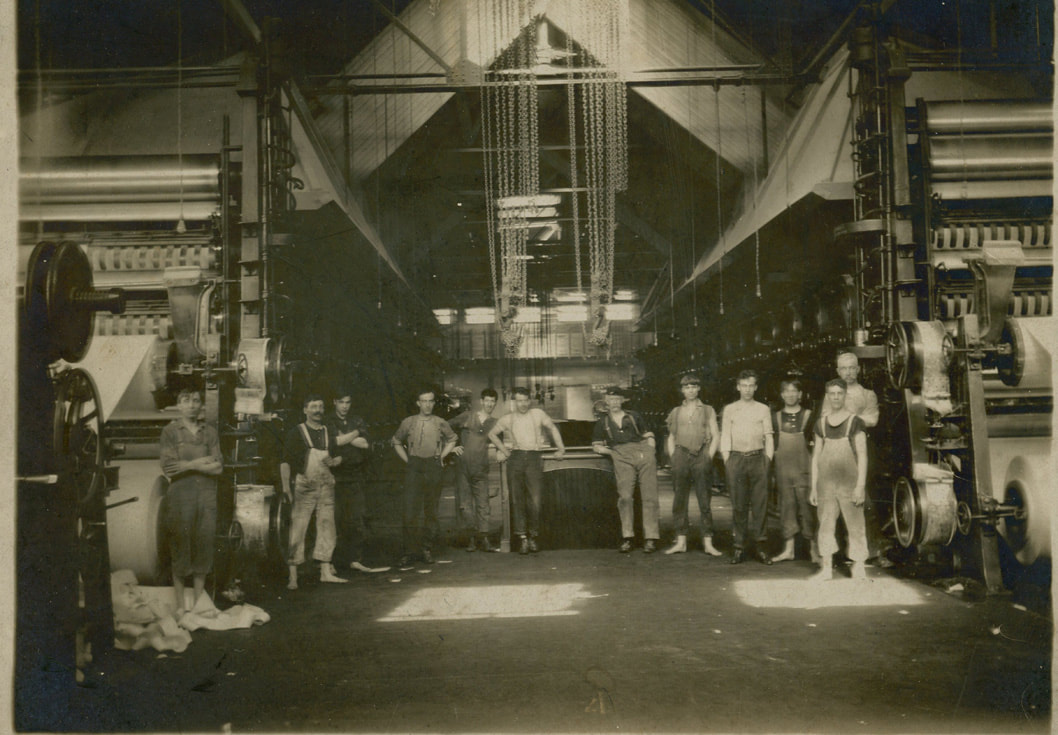

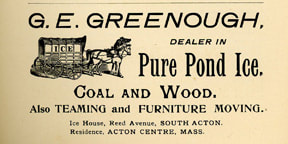

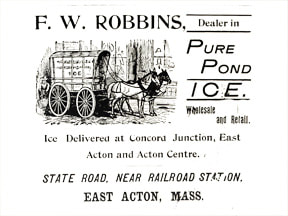

Neighbor Joel Oliver may have taken over the blacksmithing business after 1816. He was charged for coal, iron, and steel “for jumping axes” as well as leather aprons, the occasional tool, and food stuffs in the 1818-1826 period. (Jumping an axe was a term for replacing the bit/cutting edge.) Joel Oliver agreed to shoe Ebenezer’s pair of oxen and two horses for one year for $11 in January 1824. Ebenezer presumably continued with some work as a wheelwright, however, because he was paid for spokes and other work one would expect of a wheelwright later in the 1820s. The 1820 census shows that Ebenezer’s household included, in addition to 3 children, 3 males aged 16-26, 3 males 26-45, 1 female 16-26, and 1 female 26-45. Of these people, 5 were classified as being engaged in manufacturing and 1 in farming. The next household was Ammi Faulkner Adams with 3 people engaged in manufacturing. Unfortunately, the ledgers do not tell us what all of these people were creating. Many of Ebenezer Sr.’s ledger transactions in the 1820s and early 1830s seem to be related to his agricultural activities. He sold beef, pork, cheese, potatoes, corn, rye, cider and vinegar. He also sold hoop poles. In addition to his own farming, he pastured others’ cows and oxen, rented his horse and wagon or drove people himself, and took goods back and forth from Boston. Another set of transactions in the ledgers involved charges for a wide array of items beyond agricultural products. There were charges for cloth and for making articles of clothing such as a coat, pantaloons, shirts, vests and spencers (short-waisted coats). Boots and shoes were purchased or “specked” (a term for which we did not find a definition but guess it might mean repaired or resoled. One charge was for “leather to speck boots and heal”.) Other items were a silk handkerchief, shell combs, a “Parisol,” ribbon, a watch, a hat or bonnet, schoolbooks, a “Rithmatick,” and a great Bible. There were foodstuffs that would not have been produced on Ebenezer’s farm, such as sugar and molasses. On one page of the ledger, Abel Robbins owed Eben Davis for a large quantity of beef on Dec. 16, 1830 and a week later, Uriah Robbins was charged for broad cloth, buttons, skeins of silk, buckram, pasturing a heifer, a fine shirt, making a frock, and specking shoes and boots. These transactions raised a number of questions. Was Ebenezer Davis Sr. running some sort of store in his corner of East/North Acton? Was he personally creating clothing? Was he managing a clothing manufacturing business? None of these possibilities has been mentioned in town histories. Many of the accounts in the ledger were for people who were working for him, mostly close neighbors. In some instances, Ebenezer stated at the top of a page when an individual started working for him, and then listed charges. In other cases, he wrote a name and list of charges that were followed by an indication of the person’s employment, such as a list of sick days. In addition to charges for items such as clothing, the ledger shows that Ebenezer covered employees’ various needs for cash, such as at an election, at muster, at training, at Town meeting, for a mother or wife, “to pay the pedlar,” or “when you and Olive went to Concord,” and to settle bills, such as for Dr. Cowdry, "Luther Robbins for fish," or “your Taxes for 1827,” among many examples. At least two of the listed employees were noted to have lived in the Davis home for a period of time. Viewed in the light of an employment relationship, many of the ledger entries can be seen as Ebenezer Sr. making payments on behalf of employees and charging the payments against employees’ earnings. Unfortunately, the ledger is mostly silent about what Ebenezer’s employees actually did for him. It is possible that the making of shirts, spencers, vests and pantaloons was a Davis business, but it is also possible that Ebenezer was paying someone else on his employees’ behalf. Information about the Bellows Business, and More Questions The one business that later historians mentioned in connection with Ebenezer Davis Sr. and his son Ebenezer Jr. was the manufacturing of bellows. Unfortunately, information given in different sources about where and when the business operated is somewhat vague and not well-documented. The Davis ledgers and recent research paint a fuller picture than we had in the past and, inevitably, raise even more questions. Bellows would have been a common item in households and businesses in Ebenezer Sr.’s lifetime. They were used to direct a stream of air into a fire to increase the heat it produced. Bellows were manufactured by combining a wooden top and bottom with folding leather side pieces and attaching a nozzle through which air was forced as the handles were pushed together. When we started investigating the bellows business in Acton, information we had from previous historians was quite sparse. Online newspapers from the time make no mention of the Davis bellows business. Fletcher’s 1890 Acton in History said merely that “The manufacture of bellows was carried on extensively by Ebenezer Davis, senior and junior, for many years in the east part of the town.” (p. 266) Phalen’s History of the Town of Acton said that “At one time the aforementioned Ebenezer Davis manufactured bellows in a shop located on the William Davis place, later called the Bellows Stock Farm and later owned by Mr. and Mrs. Frank Griffin. The present occupant of the property is Mr. John Murphy. Eventually the shop was moved to the Eben Davis place where Dr. Wendell F. Davis now lives and where his father continued to make bellows.” (p. 156) There has been much confusion about this shop and the bellows business. The building in which the ledgers were found had come to be known as the “Bellows Shop,” but its exact history is not entirely clear. Given the fact that Ebenezer Jr.’s youngest son lived on the property and was probably the source of Phalen’s information about the building, it seems reasonable to assume that oral tradition in the family identified it as the bellows shop. In 1968, before the building was sold out of the Davis family and demolished, another discovery on the first floor was a crate, nailed shut, that contained hundreds of wooden bellows pieces, some already decorated, that were never assembled into finished products. Those pieces are now in the possession of the Concord Museum. By its architectural form, the “bellows shop” was clearly built as a dwelling house rather than a work shop. It is highly likely that this building was one of a surprisingly dense row of six houses shown on a c. 1831 map on what is now Davis Road. Deeds tell us that Ebenezer Sr. was involved in a number of real estate transactions, including purchasing a half share and then the remainder of the nearby “Ammi Wetherbee house” in 1808 and 1819. Though its exact location is hard to pinpoint from the deeds, Ebenezer’s ownership of that building raises the possibility that it was the one that eventually became associated with bellows production. By 1856, when Henry Walling mapped Acton, there were only four houses left on Davis Road, two owned by Ebenezer Sr.’s widow. An 1875 Beers Atlas map showed only one house was left on the former Ebenezer Sr. farm owned by William B. Davis, and Ebenezer Jr. had two houses, one behind the other. This seems to confirm Phalen’s assertion that Ebenezer Jr. moved the building from his father’s farm to his own. Tax valuations in 1872, 1875 and 1890 specify that Ebenezer Jr. owned a house and shop in addition to farm buildings. While many questions remain about the Ebenezers’ bellows business, the recent donation of Davis items to our Society, the information in the Ebenezer Davis ledgers, and research into deeds and other documents have given us some insights into their manufacturing activities. The first mention that we found of Davis bellows was in Ebenezer Sr.’s ledger. It involved Abraham B. Handley who had bought a new house on a small piece of Ebenezer Davis's land in 1826. On May 15, 1827, Abraham B. Handley was charged by Ebenezer $0.75 for three thousand Bellows Nails. On August 16, 1827, he was charged $0.50 to pay Ebenezer for carrying bellows to Boston. These entries imply that Handley may have been in the bellows manufacturing business first. However, another undated entry shows that Abraham Handley paid Ebenezer for 2 dozen 9-inch bellows and 3 dozen 5-inch pipes. (Given Ebenezer’s reuse of pages in his ledger, it is impossible be certain of the date, but another entry on the page is for Dec. 1831.) Could Handley and Ebenezer Davis Sr. both have been producing bellows? Was Abraham (eighteen years younger than Ebenezer Sr.) actually working for Ebenezer, or did they have a cooperative enterprise? The ledger also tells us that in Feb. 1827, Abraham’s 22-year-old sister Charlotte Handley began work for Ebenezer Sr. We do not know whether Charlotte was working in manufacturing or helping in the household. (We do know that she became Ebenezer’s second wife in 1839.) The only other early ledger entry mentioning bellows was in 1831 when Jonas Wood (another employee) purchased two pairs of swell-top bellows. Unfortunately, it seems as if pages from Ebenezer Sr.’s ledger either were removed or fell out. Ebenezer Sr.’s ledger has a decade-long gap starting about 1834 that ends with a partial transaction involving bellows, and then there are many other bellows transactions starting in 1844. Though a number of Ebenezer Sr.’s activities during the 1834-1844 period are missing, Ebenezer Jr.’s ledger, starting at the end of 1839, fills in some of the gaps. In early 1840, Ebenezer Jr. recorded buying Sheepskins, Morocco skins, scrap leather, 2 ounces of “bronze”, varnish, a varnish brush, and dozens of brass pipes. All of these were likely for bellows production. In March 1840, Ebenezer Jr. paid neighbor Ephraim Oliver for “swelling” 30 dozen boards, presumably part of the process of creating swell-top bellows. Starting in April, Ebenezer Jr. recorded sales of dozens of bellows of various sizes (flat, flat fancy, common, swell top, brass-nailed, and, later, oval and “custom”). He noted traveling to Boston, Salem, Lexington and Woburn, apparently to sell his products. Research in newspapers showed that his customers were mostly hardware merchants. The two Ebenezers seem to have made bellows separately but cooperatively. Starting In Feb. 1841, Ebenezer Jr. noted that he was delivering and selling his father’s bellows as well as his own. In March 1841, he noted that “George” had worked for “father” for seven days. Ebenezer Jr. also noted others who worked for him at times (without noting what they did) including Amos Handley, E Oliver, Kinsley, and A. Robbins. Ebenezer Jr.’s bellows sales were listed in his ledger consecutively until early 1844, after which there are only a few, sporadic entries in his ledger. Ebenezer Sr.’s ledger picks up again in 1844 with a partial entry (undated), followed by a Sept. 12, 1844 sale of 13 dozen bellows to Proctor and Butter. Ebenezer Sr.’s bellows sales continued, including some sales to his son. The last entry was on Nov. 8, 1849. Perhaps Ebenezer Sr. had run out of pages in the ledger, but there are no more entries after 1849. One point of confusion among local historians is how long the Davis bellows business actually lasted. Ebenezer Jr.’s ledger had some blank pages and some that were used for mounting newspaper clippings, so there was room to record more bellows transactions if there had been any. He did record several pages of charges to the account of Silas Conant from July 5, 1849 to Dec. 1853, none involving bellows. Those entries were mostly for agricultural products and loans of money. Toward the end of Ebenezer Jr.’s ledger is a listing of notes (loans) from 1845 (including some involving his brothers-in-law) and a few other transactions. There is one random mention of bellows without a date or a customer at the back of the book, but there is no evidence from either Ebenezer’s ledger that the business continued beyond 1850. Ebenezer Sr. died in 1851. His probate inventory listed bellows and bellows stock worth $150, the highest-value item in the listing aside from real estate and bank stock. Ebenezer Sr. also had many items and products related to his farm, including animals and swarms of bees. There were “shop tools,” “wood in shop,” “lumber in shop,” and “old lumber in old house,” but we have no other information about what those buildings were used for. It could reasonably be conjectured that since the “old house” contained “old lumber,” perhaps it could have functioned as a workshop for fabricating the bellows. Bedrooms on the second floor may have been used to house workers on the farm. Phalen indicated that Ebenezer Jr. moved the “bellows shop” building onto his own farm and used it to continue bellows production. An 1855 manufacturing census listing tells us that Ebenezer Jr. did carry on making bellows at least that long; he was listed as selling $300 of bellows that year and employing 2 hands for 3 months. We have not found evidence of his bellows business after that. Ebenezer Jr.'s Other Businesses Ebenezer Jr. certainly did not stop moving. Searches in online newspapers for mentions of Davis bellows yielded instead the insight that Ebenezer Jr. was a proud promoter of his agricultural products. The Boston Cultivator reported on Oct. 7, 1843 that Ebenezer Davis of Acton was in the nursery businesses, “bringing forward a good number of trees, though none are yet fit for sale.” In November 1845, Ebenezer Jr. advertised in the Cultivator that he had about 25, 000 New England-adapted apple trees, from one to two years growth from the bud that had been “budded by my own hands on seedling stocks, and grown on dry light sandy soil.” He offered a number of varieties including Baldwin, Greenings, Russetts, Hubbardston, Nonsuch, Lyscom, Porter, Fall Pippin, Danvers Winter, a number of “Sweet” varieties (Orange, Russett, Newbury, Andover), and more. Potential customers were invited to his Acton nursery to inspect his stock. An ad that ran in Spring 1847 was similar except that he was offering 30,000 trees with one to three years growth from bud. He also mentioned that growing them in dry, light, sandy soil ensured “a good supply of excellent roots.” (Massachusetts Ploughman, April 17, 1847). Apparently, farmers sometimes sent produce to newspapers for review. Ebenezer Davis sent the Cultivator several varieties of apples along with detailed comments on the different varieties written by his brother-in-law Harris Cowdry that were published on Nov. 13, 1847. On January 27, 1849, the Massachusetts Ploughman reported that the Middlesex Society of Husbandmen and Manufacturers had appointed a committee “to examine Farms, Reclaimed Meadows, Compost Manure and Fruit and Forest Trees.“ Twenty-eight farmers, including Ebenezer Davis, Jr., had applied for prizes for the best farm. The committee visited the farms and awarded second place to Ebenezer Davis, Jr. Helpfully, the newspaper used Ebenezer’s application to describe his 140-acre farm. Sixty acres were woodland, thirty were pasture, and fifty were under cultivation. His soil was light and sandy. In 1847, he raised corn (producing over 400 bushels) on ten acres, among which he also grew beans and pumpkins. He had recently broken ten acres on which he raised 154 bushels of rye, and he raised 200 bushels of oats on six acres. He raised 500 bushels of potatoes, but half of the crop was diseased. He cut thirty tons of hay, kept cows that produced milk and butter in excess of the needs of his family, and raised hogs in the winter. He also had at least a horse and a pair of oxen and wintered others. He had devoted two and a half acres to his Nursery business. Ebenezer stated that he had hired help equal to three men for eight months (at $15 per month) and one man at $10 per month for the rest of the year. In the months after his application, Ebenezer Jr. had raised his barn 18 inches and put a cellar under it (half for manure storage and half for root crop and fruit storage), set out 200 apple trees, and built 30 rods of stone wall. When the Committee visited his farm in September 1848, he had sixteen acres of corn, two of potatoes, and two of rutabaga, having also raised four acres of oats and cut forty tons of “English Hay” and four of “Meadow Hay.” “About fifty acres of his farm, being chiefly worn out and stony pasture, Mr. Davis purchased in 1845. Of this portion, he had ploughed and brought into a tolerably productive condition, sixteen acres.” Ebenezer Davis Jr. farm pictures taken by Robert I. Davis c. 1890 As if Ebenezer Jr. did not have enough going on in the 1840s, he had bought the home farm of the late William Stearns down Great Road in 1845. The land had once belonged to Mark White Jr. Ebenezer Jr.’s description indicated that the land was worn out, but it included a section of Nashoba Brook (downstream from the Davis farms and the original mill site purchased by Gershom Davis). According to an 1848 deed obtaining water-flowing rights from Luther Conant who owned the land immediately upstream, Ebenezer Jr. built a dam across the brook in 1845. Ebenezer built a large mill that would utilize the water power in 1847. According to a 1969 article by Brewster Conant, Ebenezer kept another ledger or journal that documented the purchasing of materials for the mill, the digging of the cellar hole in July 1847 and construction into September of that year. Apparently, on October 1, 1847 William Schouler moved in to operate a print (flannel) works, and Benjamin Davis later operated a sash and blind business at the site. The Conant article is the only source we have found about this additional ledger. Ebenezer Jr.’s ledger (owned by the Concord Museum) has a list of his debts in Spring 1845, presumably because of the purchase of the Stearns property. Building the mill was probably expensive. Ebenezer Jr. mortgaged 100 acres of his farm to his brother-in-law Harris Cowdry for $1,000 in 1849 (with an outstanding mortgage to Keziah Stearns dated June 16, 1845.) In 1850, Ebenezer Jr. sold most of the Stearns land on Great Road to Robert Boss of Charlestown. (See blog post about Captain Robert Boss). Ebenezer Jr. kept two acres for the mill and at least part of the mill pond. Ebenezer reserved the right to cross Boss’s land to the Davis mill and factory and the right “to flow his pond over the said land to the height and in the manner said Davis and his lessees have hitherto flowed the same.” (Managing the flow of water would be critical to the successful operation of the mill.) In the 1850 valuation, Ebenezer Davis Jr. was one of the larger taxpayers in town, owning valuable buildings and tied for having the second-most acres of improved land. Despite the fact that he clearly had water rights for his mill, he was not taxed for a “water privilege,” which, along with the deed to Robert Boss, suggests that he had leased the mill usage to someone else (probably William Schouler, a non-resident whose assessment included a water privilege). Though some have suggested that Ebenezer Jr. built his mill for his bellows business, we have found no evidence that that is true, and town histories do not raise that possibility. In 1852, Ebenezer started petitioning the town to lay out a road past his mill so that he would not have to cross Robert Boss’s land. It took several attempts to get the town to fund it, but in 1854 today’s Brook Street was laid out between Great Road and Main Street, passing right by Ebenezer Jr.’s mill site. The 1860 tax valuation assessed Ebenezer’s “Mills, water power, &c.” at $2,000. Ebenezer Jr. held onto the mill until 1865 when he sold the site to Martha Ball. The deed of sale did not specifically mention a residence, only “buildings thereon,” and a mill in particular. However, two of the town’s warrant items dealing with Ebenezer’s petitions specified that the road would pass by Ebenezer’s “house and mill” or “house and Factory,” so it seems that the house on the site dates from 1852 at the latest. Presumably he rented it out, as there is no evidence that he ever lived in it. Back on the Farm Whatever Ebenezer Davis Jr.’s other activities were, he kept innovating on his farm. The Worcester Palladium of Sept. 23, 1857 reported that sugar cane was being grown in Acton by Eben Davis who had two acres’ worth and planned to extract the juice for sugar. Ebenezer Jr. continued displaying his farm produce at agricultural fairs. His tempting clusters of Sweet Water grapes at the Middlesex Agricultural Society’s exhibition were mentioned in the New England Farmer on Sept. 28, 1861. The Lowell Daily Courier of June 22, 1869 mentioned Ebenezer Davis had sent luscious strawberries from Acton. “Mr. Davis is well known as a successful horticulturist, and he has for many years been a large contributor to our agricultural exhibitions.” On Sept. 6, 1871, Eben Davis of Acton was noted in the Daily Evening Traveller for displaying a fine basket of fruit at the New England Agricultural Society’s annual fair. Never one to miss an opportunity, after the railroad came through East Acton, Eben Davis advertised in Boston’s July 13, 1872 Daily Evening Transcript “Summer Board in Acton,” offering accommodations for up to four people at a pleasant location near a depot. We did not find much mention of Ebenezer Davis Jr. in later newspapers. One might have assumed that the busy Ebenezer had finally slowed down. However, perhaps he had more to think about close to home. On Oct. 11, 1873, 62-year-old Ebenezer Davis Jr. married 23-year-old Mattie/Minnie Snow. She was born either in Germany or Massachusetts, apparently to W. and Sophie Snow. So far, genealogical research has turned up no clues about Minnie’s ancestry and where exactly she came from (and when). The couple settled on Ebenezer Jr.’s farm and had son Wendell F. Davis on Dec. 25, 1876. Wendell F. Davis was the last of the family to live at the Ebenezer Davis Jr. farm. Ebenezer Davis Jr. died July 20, 1890 in Acton. Fortunately, his grandson Robert I. Davis visited Acton and took pictures of the farm that have been donated to our Society. He also took pictures of people, presumably family members, whom we are trying to identify. More Davis Information Needed We know that as late as the 1960s, other documents existed that might shed more light on the lives and businesses of Ebenezer Davis Sr. and Jr. In addition to the Ebenezer Jr. ledger/journal that mentioned the building of the factory in 1847, there was also a journal kept by Eben H. Davis, son of Ebenezer Jr. We have only a partial transcription of that journal. It would be very helpful to have access to those documents to learn more. In addition, we have a number of photos from Eben H. Davis’s son Robert for which we do not have identification. Family photos probably exist elsewhere that could help us to identify people in the pictures. If you know more about this family or have items that could be shared, we would be grateful to hear from you. Please contact us. Some Sources Consulted

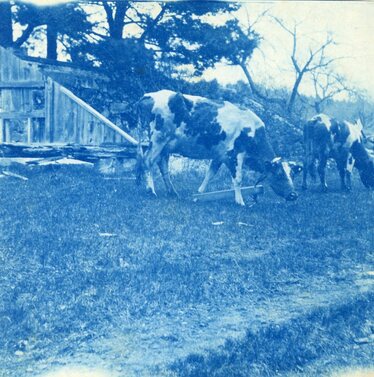

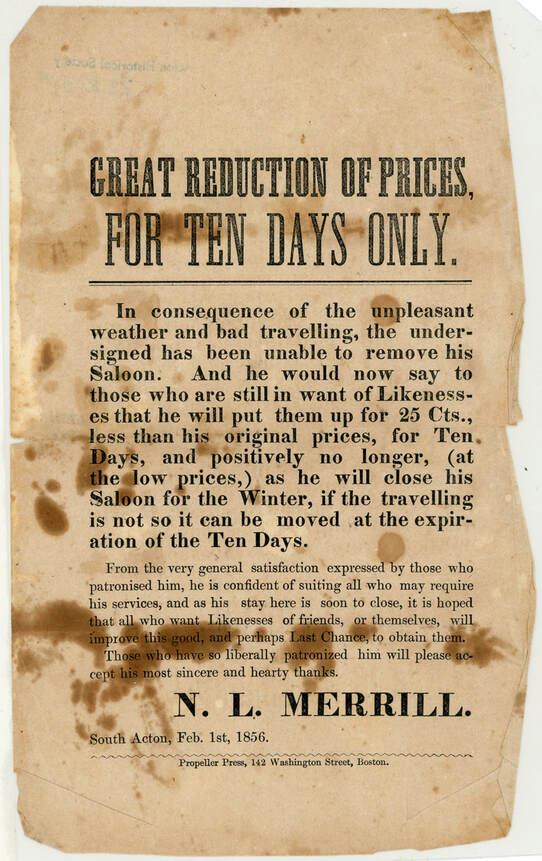

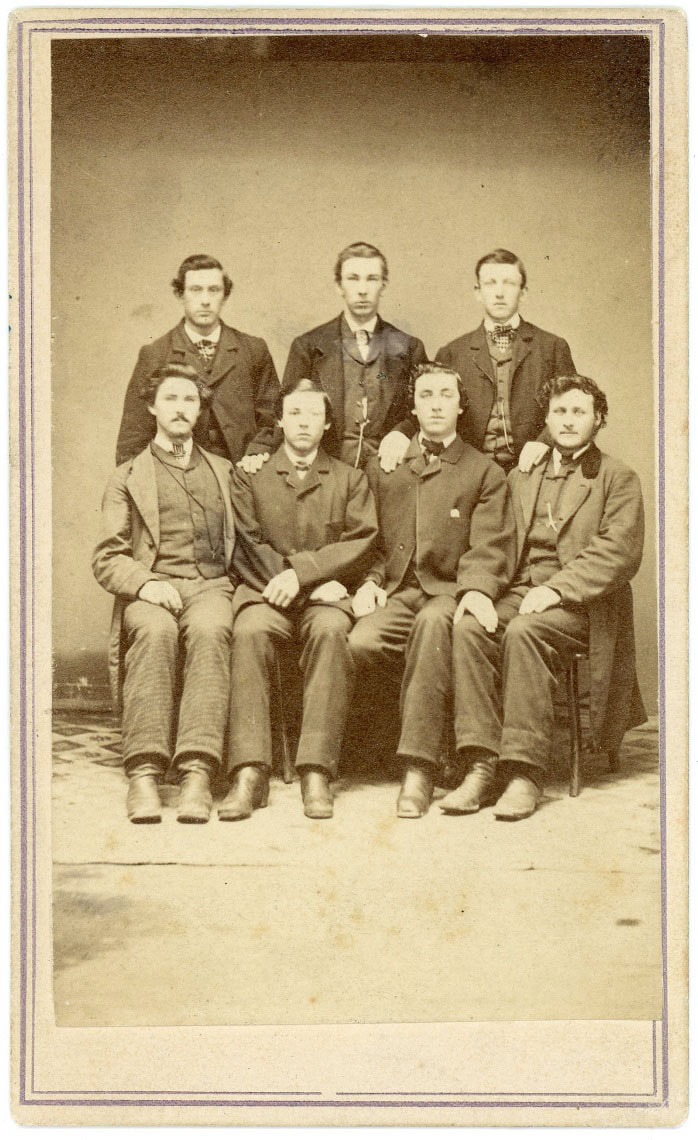

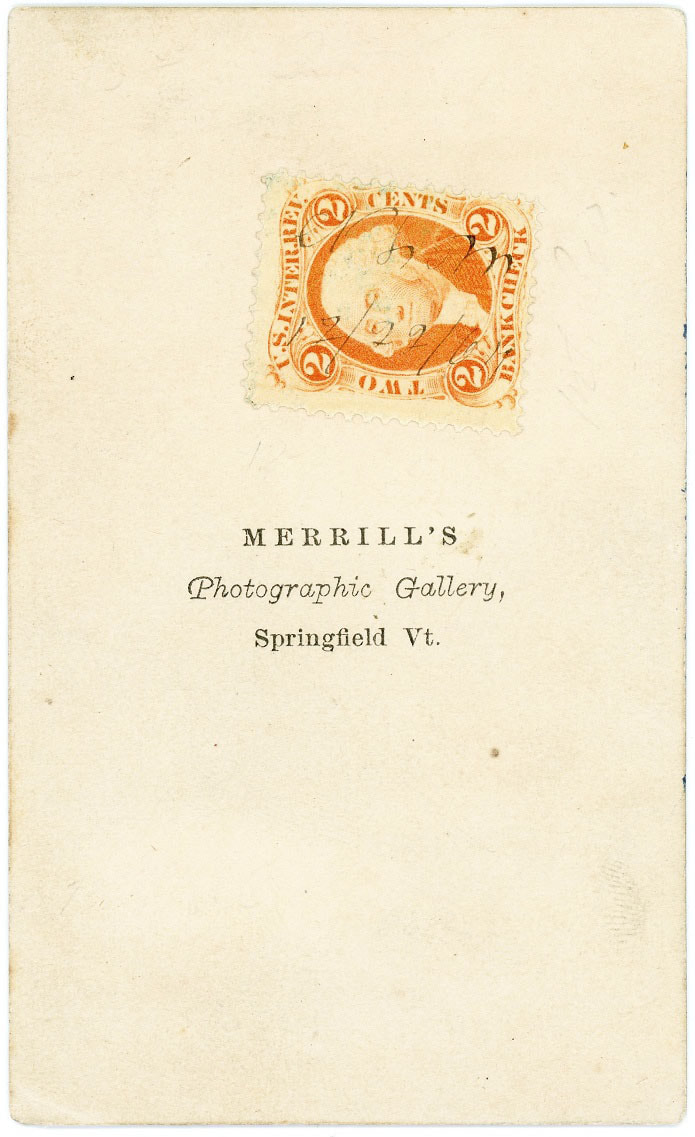

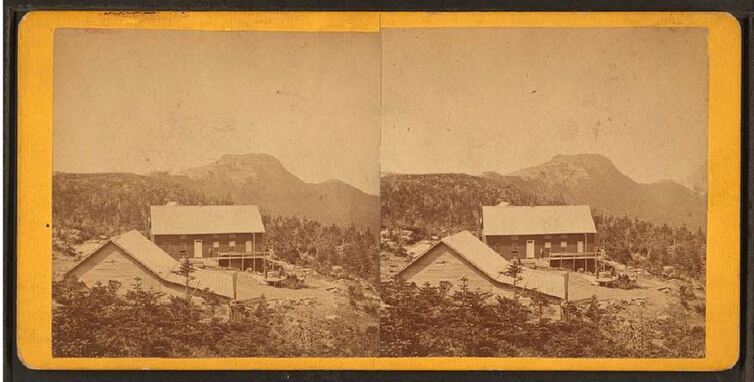

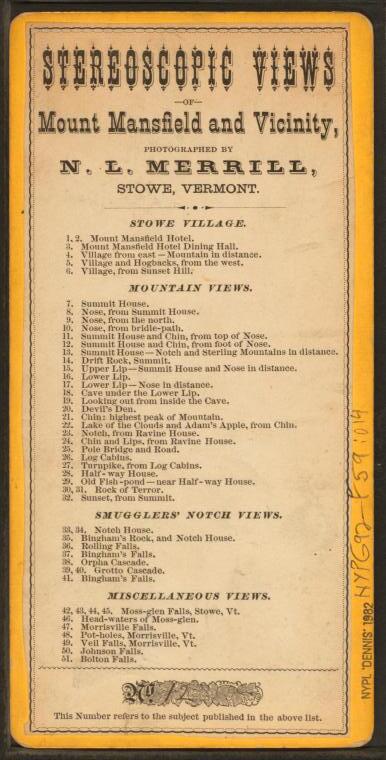

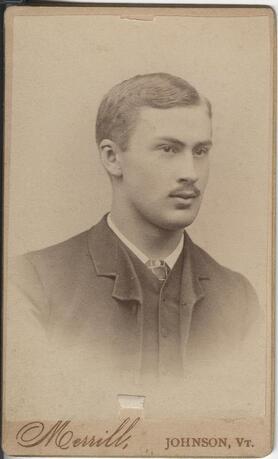

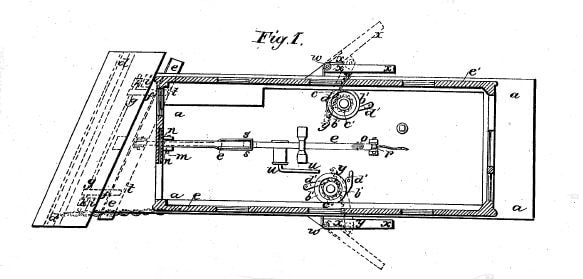

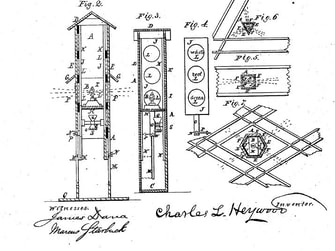

A fascinating set of handbills in our collection advertised a photographer working in South Acton in early 1856. N. L. Merrill announced on Jan. 7th that for “positively the last week,” his Daguerreotype Saloon would be operating and could save locals from going to the city to “obtain their likeness.” Pictures could be taken regardless of the weather. Merrill could even take pictures of young children “by the aid of a peculiar instrument.” He also would copy one-of-a-kind daguerreotypes and paintings. A second flyer dated Feb. 1, 1856 stated that bad weather and travel conditions had kept his Saloon in South Acton. For an additional ten days, he would provide likenesses discounted by 25 cents, after which he would move on or close down for the winter. Who Was N. L. Merrill? Curious, we consulted Steele and Polito’s monumental work A Directory of Massachusetts Photographers 1839-1900. No N. L. Merrill was listed there. Further research yielded no one of that name operating as a photographer locally, so we had to search farther afield. The only likely candidate for the South Acton Saloon’s owner was a photographer who later operated mostly in Vermont, Nathaniel L. Merrill, usually known by his initials. Oddly, we were not able to determine exactly where he came from, how he came to be in South Acton, or where he went when the weather allowed him to move on. Though historians have written about daguerreotype studios in major cities, it is very hard to learn about pre-Civil War itinerant photographers. They would have been on the move constantly, and their advertising, by handbills passed around and probably posted somewhere in town, did not generally leave traces for researchers to follow. The fact that N. L. Merrill’s South Acton flyers were preserved long enough to end up in our archives is quite remarkable. Assuming we are correct about N. L. Merrill’s identity, we were able to learn about his later career. The search took us miles from Acton but revealed the challenges of an early photographer who repeatedly adapted to changing technology and kept moving to find new markets. Digitized records, newspapers, and photographs allowed us to discover at least some of N. L. Merrill’s travels; we suspect that there were more. The early life of N. L. Merrill was difficult to uncover. The earliest information we found was a newspaper mention that “he was an excellent artist when we knew him at Irasburgh (VT), in 1850.” (Orleans Independent Standard, April 10, 1868, p.2) It seems that he traveled with a portable studio, sometimes referred to as a “daguerreotype saloon car” or a “moveable saloon.” He would presumably stay until the customers dwindled and then move on. Apparently in the course of his travels, he met Prudentia D. Waters whom he married on Jan. 25, 1853 in Johnson, Vermont. Prudentia was born and raised in Johnson, and the couple may have considered that place their home base for at least some of their time together. Unfortunately, the marriage record gives us no information that would help either to pinpoint Nathaniel Merrill’s origins or to distinguish him from many others of the same name. The record said that he was living in Portland, Maine at the time, but a Portland directory for that year yielded no photographer N. L. Merrill. Further research in the area turned up nothing useful. The next evidence of him is the pair of 1856 handbills in our archives. The 1860 census recorded him in Nashua working as an "artist," though that is the only evidence we found of him in New Hampshire. After 1860, N. L. Merrill is much easier to find because he turned to newspaper advertising and produced paper photographs with his name and location on the mats. In March 1860, the Bellows Falls Times announced that N. L. Merrill was in town with a saloon where he was taking pictures “in a very superior manner.” The enterprising Mr. Merrill had furnished the newspaper with a copied photograph that elicited a great deal of enthusiasm from the reporter. Merrill ran ads at times in the Bellows Falls Times between the summer of 1860 and at least Feb. 1862. By now he had changed technologies and was apparently settling down for a while. He announced: "MERRILL’S PHOTOGRAPH & AMBROTYPE SALOON, SPRINGFIELD, VT. The public are invited to call and examine his specimens, the only place in this vicinity where COLORED PHOTOGRAPHS ARE TAKEN. By this process life-like pictures may be obtained from old and inferior Ambrotypes and Daguerreotypes, and warranted to give satisfaction. The negative is always preserved, and persons wishing duplicates can have them at any time by ordering. LOCATED IN THE SQUARE.” (among other ads, this ran in the Bellows Falls Times, July 20, 1860, p. 4) During the Civil War years, Nathaniel L. Merrill seems to have spent a good deal of his time in Springfield. He was there working as a “Photographist” when he registered for the draft and was taxed for a photographer’s license in the 1862-1865 period. Some of his portraits from this period have been made available online including this photograph of seven young men taken in December 1864, courtesy of Brad Purinton’s Tokens of Companionship blog: The Lamoille Newsdealer of July 12, 1865 wrote that “N. L. Merrill, from Sprin[g]field, Vt., is now stopping at Johnson for the purpose of accommodating the public with any kind of a picture known to the photographic art. He has had a large experience in the business, and will be remembered by some in this vicinity as the man who first introduced a daguerreotype car into this part of the country. – He has erected a temporary saloon, which he terms a “Camp,” on the Common near Denio’s hotel, and commenced business in it on Monday last.” (p. 3) The camp was apparently well-attended and patrons’ “urgent solicitations” led him to stay in Johnson during August as well. Around this time, N. L. Merrill seems to have bought property in Johnson. He must have sold his Springfield business, because the back of a portrait taken by J. D. Powers of Springfield, Vt., says “We have also N. L. Merrill’s Negatives in preservation, and will furnish copies when ordered.” (eBay offering, August 2022) Merrill was on the move again. He ran an ad in 1866: “Mr. N. L. Merrill, the veteran artist, has pitched his ‘camp’ near the American House in this village (Hyde Park) and will remain four weeks for the purpose of supplying the people with Photographs, Ambrotypes, and Melanotypes, of the highest perfection. Copies from old and inferior pictures can be obtained and enlarged and finished in India Ink or colors, also card Photographs for the same. A good assortment of Phot[o]graphic Frames and Albums always on hand. His reputation as an artist is well established in this vicinity. Pictures can be made in cloudy as well as fair weather.” (Lamoille Newsdealer, June 6, 1866, p. 4) N. L. Merrill moved on to Cambridge Borough, VT a few weeks later. At times, he rented rooms rather than establishing a “camp.” A woman’s portrait recently offered on eBay was marked on the back “N. L. Merrill, Photographer, Rooms over Kinsley & Bush’s Drug Store, Cambridge, VT.” In April 1868, N. L. Merrill leased a photographer’s “saloon” in Barton Landing in northeastern Vermont. He was listed in the Vermont State Directory of 1870 in Johnson, though the 1870 census shows him in Montgomery, Vermont. (The entry listed Nathan Merrill, photographer, married to “Patience.” Presumably he was passing through town and the census taker did not work too hard on the details.) N.L. Merrill also had a studio in Dunham, in the Eastern Townships of Quebec where he was listed in Lovell’s Canadian Dominion Directory in 1871. The Brome County Historical Society holds a portrait taken by him there. In 1872, N. L. Merrill seems to have had a studio in Enosburgh Falls, Vermont, from which he moved on and a different photographer set up shop. A portrait posted online showed that at some point, N. L. Merrill also took pictures in Richford, Vermont. In the early 1870s, N. L. Merrill seems to have returned to Stowe, Vermont fairly often. According to the back of a portrait available online, he set up shop in Stowe with a company name of “Mt. Mansfield Picture Gallery.” (Another photo for sale on ebay showed the same gallery with a different photographer, so he may have bought out or sold to a photographer named O. C. Barnes.) In December 1872, N. L. Merrill closed his Stowe gallery for a few weeks and went to Rouses Point, across Lake Champlain in New York. The back of a photograph recently listed on ebay confirmed that N. L. Merrill indeed took pictures in Rouses Point. Merrill was in Stowe again in October 1873 but planned to pack up soon “and go where there are more faces.” (Lamoille Newsdealer, Oct. 15, 1873, p.4) In 1874, he reappeared in Stowe In May and September when the Argus and Patriot reported that N. L. Merrill was “again prepared to make those new style photographs.” (Sept. 3, 1874, p. 3) In addition to portraits, he took a series of Stereoscopic Views of Stowe Village, Mount Mansfield, Smugglers’ Notch and a number of nearby waterfalls. An advertisement for his gallery in Churchill’s Building in Stowe mentioned that he stocked frames, albums, brackets, knobs, and cords, along with a collection of stereoscopes and stereoscopic views. Unfortunately, there was quite a bit of competition in the “view” business, so it may not have been profitable for him. We have not found that he did any other series. The New York Public Library has a stereoscope view taken by N. L. Merrill available online, and the reverse side shows his other subjects. N. L. Merrill returned to Johnson repeatedly; by the 1870s, it was clearly his home base. In Dec. 1876, N. L. Merrill of Johnson was “taking all kinds of pictures at the photographic gallery of Mrs. B. W. Fletcher” in Waterville, VT. (Burlington Weekly Free Press, Dec. 15, 1876, p. 3) An ad in the April 25, 1877 Lamoille Newsdealer announced that N. L. Merrill would keep his Johnson photographic gallery and saloon open a few weeks longer. In July 1879, Merrill did a short stint in South Troy, Vermont, but then returned to Johnson. Nathaniel, “Photographist,” Prudentia, and daughter Mary were living there at the time of the 1880 census. The two photographs below have been made available online by Special Collections at the University of Vermont's Baily/Howe Library. Both have “Merrill, Johnson” printed on the mats. They were identified on the backs with a name, hometown, and “Classmate J. S. N. S.,” referring to Johnson State Normal School; its students would have been a good source of business for a portrait photographer. We found less frequent evidence of N. L. Merrill’s activities in the 1880s, but he was still at work. He set up a studio in Enosburgh Falls, Vermont in September 1883, but he was listed in the Lamoille County Directory of 1883 and the 1887 Vermont Business Directory as a Johnson photographer. In November 1885, daughter Mary was married to Hannibal Best at the Merrill residence in Johnson. A quit-claim deed dated Nov. 14, 1888 shows that Nathaniel, his wife Prudentia, her nephew Samuel H. Waters, and his wife Juliette sold lands and tenements in Johnson. (Three mortgages had been executed on the property/properties in 1865, 1869, and 1872.) N. L. Merrill was apparently still living in Johnson, however, while taking photographs in Waterville in Sept. 1889. In Feb. 1890, the St. Albans Daily Messenger reported that N. L. Merrill, who had had a photographic business in Johnson for many years, was moving to live with his daughter and her husband Hannibal H. Best in Enosburgh Falls. The News and Citizen reported that he was dangerously ill in mid-February 1891 and that he died in Enosburgh Falls on Feb. 26, 1891. Unfortunately, we have not found a death record or full obituary for him. A burial notice in the St. Albans Messenger on March 5 said that he had been an invalid for years, but according to an advertisement in the News and Citizen, he had been working as a photographer in Johnson as late as January 1890.

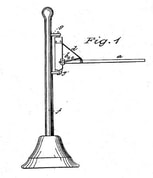

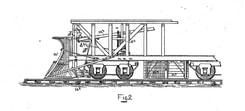

Back in Acton When we first found the flyers for N. L. Merrill’s daguerreotype saloon, we thought that he would be local and that we could easily track down his life story. What we discovered was Nathaniel L. Merrill, a Vermont photographer who had to be on the move constantly in the decades that followed 1856's saloon. We pieced together many of his movements after 1860 from digitized newspapers, records, and photographs, but we were not able to trace his origins. Different records gave his birthplace as Maine, New Hampshire or Massachusetts, and we found no source that mentioned his parents or siblings. Most of his early travels with his daguerreotype saloon in the 1850s are also unknown, including why he came to Acton (assuming our identification is correct). Any additional information would be appreciated. Clearly by 1856, the people of Acton, and South Acton in particular, could easily have had their pictures taken if they could afford it. One has to wonder what happened to the likenesses taken that winter; we would love to have scans of local pictures taken by N. L. Merrill. The Society and Iron Work Farm have rare pictures taken of local buildings lost to fire in the 1860s. They could have been Merrill’s work, or perhaps there were done by other itinerant photographers who offered their services in mid-nineteenth century Acton. It is even possible that we could have early N. L. Merrill pictures in our collection. Unlike paper photographs with mats that showed the photographer, location, and sometimes the subject of the picture, early photographs in their metal or leather cases were much harder to label. We have a collection of beautiful early portraits of unknown people done by unknown photographers; it is frustrating that no one labelled them while there was a chance of identifying them. (A selection is here.) Photography was new at the time; perhaps people simply did not imagine that eventually likenesses would survive but people’s memories would not. If your Acton ancestors’ likenesses or their photographs of local scenes are in your possession, we would be very grateful to add scans (or originals) to our collection. Please contact us. Sources Used (in addition to standard genealogical resources):  C. L Heywood [43] C. L Heywood [43] Ann F. Heywood, subject of our last blog post on Acton’s first female voters, was married to Charles L. Heywood, owner of a South Acton mill. We had very little information about them to start, but our research revealed that they were celebrities by the standards of South Acton in the 1870s. Charles, as it turns out, was unusual by any standard. Ann evidently was herself worthy of note, but, as is frustratingly typical, she was much less documented in written records. The Early Years We do not know much about Charles and Ann's early lives. Records of that time are sparse, and neither Charles nor Ann grew up in Acton. We do know that Charles Lincoln Heywood was born to Lincoln Heywood and Rebecca Priest in Lunenburg, MA on April 17, 1828. The eighth child in the family, he grew up in Lunenburg and was educated in its local schools. His father was Deacon of the Unitarian Church. About the time that the Fitchburg Railroad came through Lunenburg (approximately 1845), Charles went to work for the line as a crossing tender. Charles was obviously a young man of ability; he moved up steadily in the railroad's ranks. By 1850, 22-year-old Charles was living in Fitchburg with the Israel Goodrich family and working as a Wood Agent for the railroad. In the 1855 Massachusetts census, he still had that title and was living in a "hotel" in Fitchburg. Within the next year or two, Charles was promoted to Roadmaster, a managerial position responsible for track conditions and safe operations. He continued to serve as Wood Agent as well, at least at first. Charles soon moved to Concord, MA, where he joined the Corinthian Lodge of Masons. He was a resident of Concord when he married Ann Tyler. [1] Ann Frances Tyler was born June 18, 1825 in Attleboro, MA, the fourth child of Samuel Tyler and Betsey Samson. Ann was only three when her mother died. According to a Tyler genealogy, her father was "an enterprising, influential man in Attleboro, and a pious church-member. His will mentions him as 'a depraved worm of the dust.'" It appears that Ann and Charles both grew up in homes in which religion was important, but beyond that, we do not know any more about their upbringing or how they managed to meet. They were married on November 25, 1857 either in Attleboro or in Providence, RI where Ann was living at the time. [2] A Busy Life The couple moved at some point to Belmont, MA where Charles was living when he registered for the draft in 1863 and where he became a charter member of the local Masonic lodge. In September 1864, after many years of service, Charles was promoted to the position of Superintendent of the Fitchburg Railroad. He would serve in that role for about fourteen years. [3] Charles seems to have possessed an unusually active mind and the energy to turn his thoughts into reality. Apparently, it was his idea to create the amusement park at Walden Pond in Concord that opened in 1866. Though Charles grew up in Lunenburg, his family roots went way back in Concord. His relatives seem to have owned a significant portion of the shoreline of Walden Pond, and the Fitchburg Railroad conveniently went right by. The railroad bought up land bordering the pond and cleared some of the woods to create an entertainment area with a large hall for use as a dancing pavilion or a gathering place for large meetings. Tables and seats were provided for picnicking, and for the more actively inclined, there were trails, swings, “teeters,” bathhouses for swimmers, and rowboats. People were delivered by train right to the park that was usually called some variant of “Lake Walden” or “Walden Pond Grove.” [4] Though to many today, Walden Pond should be kept as pristine as Thoreau saw it, at the time, many would have considered the park a societal benefit that allowed city dwellers a respite in fresh air and a beautiful spot. It was enormously successful. A Waltham Sentinel reporter, having recently enjoyed “a fine boat ride with several of the Fitchburg railroad officials, accompanied by their ladies; among the party Mr. Heywood, the Superintendent,” wrote that the park was “rapidly becoming quite popular.”[5] J. C. Moulton, “a well known Artist from Fitchburg” was there that day with his “machine” for making stereopticon views for sale, which would have been good to promote the park. The first season of the venture was summed up in the Nov. 30, 1866 Waltham Sentinel; the Fitchburg Railroad had brought out thirty different groups to the grounds, about 10,000 persons, without mishap. [6] The venture grew from there. By June 1869, large boats with side wheels and docks to accommodate them were added. During its first five years, newspapers reported that Walden hosted gatherings of veterans, temperance advocates, Masons, Good Templars, Sunday Schools, Spiritualists, and students and alumni of the New England Conservatory. In July 1869, the "Grand Temperance Celebration" featured speakers, music, dancing, boating, swinging, ball playing and a Velocipede rink. The special excursion admission and train fare from Acton was 50 cents. The third annual Musicians’ Picnic in 1870 drew more than 3,000 people to hear at least seven bands including Acton’s 19-piece band led by G. Wild. On July 4, 1870, the estimated crowds were 8,000-10000; the railroad used every serviceable car to accommodate them. In the early years of the 1870s, trains started bringing “the children of the poor” out from Boston to enjoy a day at the amusement park. [7] Walden was only one of Charles L. Heywood’s brainstorms. As Superintendent of the Fitchburg Railroad, he conceived numerous special excursions to provide people with recreation, edification, or simply a change. In addition to promoting events at Walden and closer to the city, the railroad carried people to West Townsend and environs to gather greenery, trailing arbutus, checkerberries and mosses with which to celebrate May Day. Excursions were arranged for people to see the engineering wonder of the Hoosac Tunnel. Superintendent Heywood invited the famous Rev. Henry Ward Beecher to preach at Lake Pleasant, a Spiritualist campground in Sept. 1875. Montague depot was nearby. [8]  Bridge Guard Bridge Guard Charles’ mind was also busy thinking of ways to make the railroads safer. In 1866-67, he was granted patents for a railroad snow plow and a “bridge guard” to keep brakemen from being knocked off the top of railroad cars as they worked. Charles’ plow, apparently “ingenious,” efficiently and thoroughly cleared the tracks. Adjustable “wings” could clear five feet on either side of the tracks and would retract if they hit an obstacle. His plow was used, at the least, by railroads in Massachusetts, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin. Charles’ “bridge guard” was “a light movable crane” that would give brakemen working on top of railroad cars warning before they were hit by the bridge.[9] It apparently was widely adopted, as it “proved a great protection against accidents.”[10] Charles may have traveled to promote his inventions. In addition to exhibiting at the 1865 Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association in Boston, he was also one of the exhibitors at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia.[11] Charles became known as a strong advocate for railway safety: “Even the ordinary signs at crossings he did not consider sufficient, and the reading on many of them he had so amended as to direct travelers to ‘look both ways’ before attempting to cross the tracks. There was no device brought to his attention that promised to reduce the chances of accidents which he did not forthwith adopt.” [12] Charles and Ann seem to have moved around. They may have stayed in residential hotels at times and may have had multiple properties at others, but they were always near the railroad. In May 1866, Charles bought a house on Main Street, near the corner of Auburn Street, in Charlestown, MA. He and Ann joined Harvard Church there in early 1868, and in May 1869, an ad appeared in the Boston Traveler “For Sale or To Be Let on a Long Lease – A good House, Stable, and 17,000 feet of land, well stocked with fruit and shade trees, near Waverly Station, Belmont, Mass. Inquire of C. L. Heywood, at Fitchburg Railroad, Superintendent’s Office.”[13] Charles transferred his Masonic membership to Charlestown in November, 1871. For some reason, we were not able to find Charles and Ann listed in the 1870 census; perhaps they were traveling at that time or staying at a summer location, possibly in South Acton. As far as we can tell, Ann and Charles had no children of their own. Around 1870, Ann’s niece, Eunice Tyler (Read) Crawford, daughter of Ann’s sister Eunice and wife of George Crawford, passed away. She left a child, Herbert Lincoln Crawford, who had been born in Pawtucket, RI in September 1868. Charles and Ann took him in. Whether or not the arrangement was meant to be temporary, it became permanent, and in 1878, while living in Belmont, the couple adopted the boy. His name was changed to Lincoln Crawford Heywood. Abundant Charity While still working for the railroad, Charles gave of his prodigious energy and his money to charities. He took special interest in the welfare of the inmates of the Charlestown state prison and taught Sunday school there. The Boston Daily Advertiser noted in January 1870 that he had given his students a book of their choice as a Christmas gift. He was also involved in the Massachusetts Society for Aiding Discharged Convicts. His belief in rehabilitation was obviously deeply held, because his kindness to prison inmates extended to the man who had killed Charles’ brother George. According to Cunningham’s History of Lunenburg, Charles met the prisoner responsible for his brother’s death, forgave him, and actually helped to get him pardoned. We were able to confirm the pardon but not Charles’ role in it. Cunningham was well acquainted with Charles’ father and apparently knew Charles, so presumably he heard the story from someone who knew what happened. [14] Prisoners were not the only beneficiaries of Charles’ generosity. Charles served on the Executive Committee and as director of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals for years and took an active part in the Massachusetts Total Abstinence Society from its beginning. He was involved in creating excursions for poor city children, including to Walden. In 1874, to kickstart a fundraising campaign for the debt-ridden Appleton Temporary Home for Inebriates, he offered to pay down one-tenth of its debt and to donate $10 yearly for the rest of his life. In 1875, he supplied every school district in his native town of Lunenburg with a cabinet organ and a full set of songbooks and donated money to the Lunenburg farmers’ club to encourage them to plant forest trees. Later, he donated globes and microscopes to the Lunenburg schools. Charles was also one of the founders of the Boston Union Industrial Association whose purpose was to find employment for and give assistance to the poor. [15] Ann (Tyler) Heywood showed up in newspapers in the 1870s, sometimes attending an event with her husband, but sometimes on her own. Ann was a donor to the North End Mission nursery. She served food (as did men) during at least one of the Poor Children’s Excursions to Walden, and in 1875 she and Charles were both appointed to the Committee in charge of Poor Children’s Excursions from the city. Ann served on the committee on her own for several years. In 1876, Mrs. & Mrs. C. L. Heywood were given a seven-piece silver tea service “as a token of appreciation of their generous gift of the reading room to the village of Waverley.” [16] Acton Connection In the 1870s, the Heywoods came to South Acton. As far as we can tell, their involvement started with a business opportunity. In 1869, William Schouler, owner of a South Acton mill, decided to sell out. An ad said “WATER POWER FOR SALE – Consisting of two privileges, within 30 rods of each other, one of 16 and the other of 9 feet tall, on an excellent stream, with a reserve of two ponds of 400 acres, altogether independent of the stream, with good factory buildings and dwelling houses, several acres of land with orchard and large grapery, situated on the Fitchburg Railroad, near the depot at South Acton, about 1 hour’s ride from Boston.” [17] Charles Heywood purchased the property on April 27, 1870 with a mortgage. In November, the old Schouler Mill burned, with damage estimated at $3,000. Fortunately, Charles had it insured. [18] Charles started a soapstone mill at the South Acton site. We were unable to find any details about the soapstone mill, unfortunately. There were soapstone quarries elsewhere in Massachusetts and in Vermont; Charles presumably was able to ship raw materials to Acton easily by rail. We were able to discover some details about Charles’ property from Acton’s 1872 tax valuation: Heywood, C. L., Belmont --