|

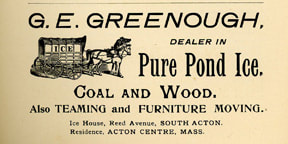

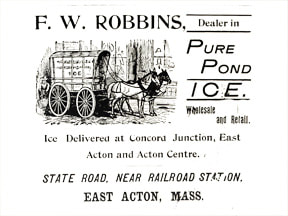

1/6/2018 Cold Isn't New - Ice in Acton Ice House, East Acton Ice House, East Acton Massachusetts has been experiencing a very cold start to winter, making us think about how Acton’s former inhabitants dealt with plunging temperatures. A century ago, the January 1918 Concord Enterprise reported the effects of “Jack Frost” on the people of Acton and surrounding towns. Plumbers were reported to have worked “day and night and through the New Year’s holiday repairing water pipes and frozen meters.” (Jan. 2, page 5) In Maynard, the American Woolen Company, a large employer and landlord, utilized its “electrical thawing machine” to help where possible with the frozen pipes in 100 of its houses. On the 16th, the paper reported that “many calls were sent in to the plumbers who were simply unable to accommodate everyone.“ (page 1) Current Acton residents and harried plumbers might assume that the news item was just written this week. There were people, however, who welcomed periods of deep cold. In the era before refrigeration, ice cut from local ponds and streams could be stored away to chill perishable goods in the warmer months. Though ice is known to have been used and stored earlier, after Frederick Tudor and Nathaniel Wyeth developed the ice industry in the early- to mid-1800s, cutting ice and using it to chill fresh food became widespread. In the late nineteenth century, ice was no longer viewed as a luxury for the rich but as a necessity. By 1900, most homes were able to store fresh food in an insulated wooden icebox that was lined with zinc or tin. To supply them, the ice man would make his rounds with blocks of ice; consumers would leave a sign in the window if they needed ice that day, specifying the weight of the block they needed. The ice man would use large ice tongs to handle it. Where there was demand, businesses grew up. There was considerable competition in the ice business, and most local ponds became a winter resource, Acton’s included. For ice harvesting to be practical, the ice had to be at least eight inches thick and preferably more, as harvesting required horses and men to be out on the ice. Hayden Pearson’s The New England Year (1966, pages 18-20) describes the basic process, and the US Department of Agriculture's Harvesting and Storing Ice on the Farm (1928) adds many details. When the ice was deemed to be thick enough, workers would rush to harvest it. Snow needed to be cleared, preferably by horse power, using a board placed between the runners of two-horse sleds, angled as in modern street clearing. After clearing, horse-drawn "plows" would groove the ice two to four inches deep. Making sure the first line was straight was critical; some farmers used a long board lined up with stakes as a straight-edge. For subsequent grooves, a guide attached to the plow was used to keep the lines parallel. The plows would then create grooves at right-angles so that blocks could be produced. (The lines needed to be quite accurate, or there would be waste and problems in stacking and packing the ice in storage.) After the ice was scored, the sawing would begin. Individual harvesters (sometimes including boys released from school) would hold the four-foot ice saw's crossbar and saw up-and-down along the grooves. It was hard work. Hayden Pearson remembered from his youth aching backs and shoulders and being exposed to a miserably cold wind blowing across a pond during harvesting at zero degrees or less. To transport the sawed ice, a channel was cut to the shore. The blocks were then pushed through the channel with long-handled hooks. Alternatively, sometimes the ice would be floated in long strips, and then the blocks would be separated with a saw or a splitting fork before loading. In Pearson’s case, the ice was loaded on a sled and taken to his father’s farm ice house. In larger enterprises, the ice house might have been located near the pond or at the ice dealer’s business. The blocks were loaded into the ice house layer by layer, covered with sawdust in between layers and surrounded by a foot of insulating hay or sawdust next to the outside walls. A ramp was used to push the ice up higher. Commercial ice harvesters probably used Wyeth’s labor-saving two-bladed ice “plow” and a conveyor belt operated with pulleys or a horse-powered "elevator" to load the blocks of ice and the insulating sawdust into their ice houses. In later years, trucks and tractor engines would be used, but the essence of the process was similar to Pearson’s father’s. It was a tough business; ice cutters had to wait until the ice was thick enough to work on safely but get the ice harvested before a thaw. Given how hard it is to predict the weather today, one can imagine that timing was tricky in earlier days. In December 1898 (Dec. 29, page 8) the Concord Enterprise reported that local businessmen Tuttles, Jones and Wetherbee had grooved their ice already, but the weather turned against them, necessitating a wait for more cold. A significant thaw or precipitation might mean that the work would be ruined. On Jan. 2, 1896 (page 8), the Concord Junction reporter noted the ice was 9 inches thick the previous week, but now it was probably 2 inches thick and honeycombed. Another reporter gave offense to a Hudson (MA) ice dealer by commenting that Berlin (MA) ice harvesters had managed to get ice before the thaw, but Hudson’s had not. It was a temporary problem; a week later, South Acton news reported “Sixteen below zero on Maple street Monday morning, and the ice scare is now over.” (page 8) Ice had become so important by that time that papers reported on ice shortages as major problems. For example, the April 4, 1890 issue of the Acton Concord Enterprise (page 3) reported on "rising prices for ice and the rush of the speculators to obtain all they can on the lookout for an ice famine.” The Enterprise often reported on ice cutting and the filling of ice houses at various Acton locations. The longest-remembered operation was at Ice House Pond in East Acton where commercial ice cutting seems to have occurred from the 1880s into the 1950s, though ice demand decreased substantially after home refrigerators became common. A large ice house was located next to the pond. (See Tom Tidman’s history of ice cutting there and Acton Digest's Winter 1989 article about later years' harvesting at the pond, available at Jenks Library.) Other locations for ice cutting mentioned in local newspapers were Grassy Pond, Lake Nagog, the mill pond in South Acton, and W. H. Teele’s property in West Acton (accomplished by damming Fort Pond Brook on his property in part of the wetland area now between Gates and Douglas schools). There were undoubtedly other sources; it is estimated that there were about a dozen ice houses in town. The newspapers mentioned ice houses belonging to Tuttles, Jones, and Wetherbee in South Acton, Freeman Robbins in East Acton, W. H. Teele, L. W. Perkins, A. F. Blanchard, and A. and O. W. Mead in West Acton, and George Greenough and W. E. Whitcomb, as well as unspecified milk dealers and the railroad (that transported milk to the city). These owners and businesses would hire men on a contract basis to put in long, intense hours while the weather held. For example, the February 2, 1899 Enterprise noted in West Acton that “The ice business of A. and O. W. Mead is rushing with 15 teams and 42 men. They have been cutting about a week and the ice is very thick.” (page 8) Reporting usually noted the thickness and quality of the ice. The danger to the workers was seldom mentioned. However, in 1917, a report did mention frostbite: “Some of the best ice seen this season was hauled to the ice house of W. E. Whitcomb Saturday from Grassy pond. It was about 14 or 15 inches thick. Although the work was not completed filling the house, the work will be finished later. Otto Geers of Stow, one of the drivers, froze his cheek.” (Feb. 7, page 7) Aside from the cold, working on ice was inherently hazardous. In February 1908, the ice broke, sending one of the ice teams of Webb Robbins into the water. For a while, "it seemed as if the entire outfit would go to the bottom. The wagon was finally gotten out, but the load was a loss." (19th, page 1). Coming back to the record-setting cold of December 1917-January 1918, not surprisingly, ice was harvested early and was of great quality that year, up to 27 inches thick. The cold snap brought with it a “mysterious quake” felt during the night in South and West Acton. (Concord Enterprise, Jan. 2, page 5) Residents who were awakened from their sleep wondered if a powder mill or their boiler had exploded. Later, based upon fissures found in Maynard, the noises were attributed to a “frost quake.” The same cold froze not only residents’ water pipes but also the apples and vegetables stored in their cellars. A coal shortage that winter compounded people’s misery and delayed January’s school opening. Some took advantage of the cold to skate, play hockey or go ice fishing. Aaron Tuttle was reported on January 23 (page 1) to have gotten “16 nice pickerel out of the mill pond.” Others had to make concessions to conditions. In Concord, on January 16th, a news item reported that “M. B. L. Bradford has had the lights of the Concord Curling rink cut out of the town’s electric circuit, to help save coal. Though this cold winter has furnished perfect ice for curling, since Dec. 12, the rink has not been used once for the 8 to 10 o’clock evening play.” But even in that winter, the weather was fickle; the same column mentioned recent rain and warmth ruining the ice in the Middlesex School hockey rink (page 1). Winter, regardless of the era, brings its own challenges. Ads for ice dealers found in a 1902 Acton directory in the Society's collection.

Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed