Revolutionary War Soldiers Remembered Belatedly, Part 2 Research for our previous blog post on Revolutionary War soldier Isaac Ramsdell led us to a list of men recruited for service in the company of Capt. Wilbur Hudson Ballard (General Nixon’s Brigade, Col. Ichabod Alden) that included Acton soldiers Stephen Shepard and James Emery. The document stated that James Emery was killed in service on Oct. 8, 1777. We were very surprised to discover a second Acton resident who had died in service but was not on Rev. Woodbury’s list of local Revolutionary War soldiers and was not mentioned in our local histories. Unlike Isaac Ramsdell whose early life is still unknown to us, James Emery had clear Acton roots. James’ grandfather Zacariah was mentioned in some of the earliest town meeting records. (Though he is said to have lived in Chelmsford, he must have lived in Acton in some of those years, as he was chosen as highway surveyor, constable, and committeman in several town meetings). James’s father John was born in Chelmsford but settled in Acton on land owned by Zechariah. John appears in town meeting records starting in the 1750s. He served as highway surveyor and constable for the town. John and Mary Emery had a large family, most of whom show up in Acton vital records:

John Emery, James’ father, was listed as a member of Acton’s Alarm Company #2 in 1757, doing militia duty at the time of the French & Indian war. (There does not seem to be a record of his going to Canada during that time.) By the mid-1770s, the political sympathies of the Emery are quite clear. James’ brother Joseph was on the 1774 sign-up sheet of Acton men who formed a militia company under Captain Joseph Robbins, thinking themselves “ignorant under the Military Art and Willing to be Instructed.” John Emery appeared on Captain Joseph Robbins’ list of men who were under his command on May 15, 1775 and for the year 1776. (It is unclear from Captain Robbins’ list whether John Sr. or Jr. is on the list, or both. John Emery is the only name that shows up twice. It is possible that both father and son were meant, without specifying a “Jr.”, or that John Jr. did two different stints, or perhaps a different Emery was meant. Depending on the source, John Sr. is either credited with Revolutionary War service or not.) Fortunately, James Emery and his brothers did show up in other records. The compendium Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War has three entries for James. In one, a “James Emery, Concord,” was listed as “Private, Capt. Asahel Wheeler’s co., Col. John Robinson’s regt.; marched Feb. 4 [year not given, probably 1776]; service 1 mo. 28 days.” Given that he was assigned a town of Concord, this might seem to be a different James, but similar entries involve his brothers. John Emery, “Acton (also given Concord)” and Samuel Emery were credited with the same service. Acton’s John Oliver also served in that company and testified in his pension application that he was stationed in Cambridge at “the colleges” during that period. Another entry for James Emery came from a “List of men raised to serve in the Continental Army from Capt. Simon Hunt’s co., Col. Eleazer Brooks’s regt.,” dated Acton, Sept. 5, 1777. Simon Hunt mentioned:

The title of Simon Hunt’s list implies that all three men served at some point in Simon Hunt’s company, although we have found no other information about that service and have not seen an original or scanned copy of that list. The Massachusetts Line went through various reorganizations as the war progressed. During 1777, there was a great deal of organizational change and a focus on much-needed, longer-term enlistments. Records can be confusing as a result. Pay and muster records state that James Emory of Acton enlisted on April 14, 1777 for a period of 3 years. He served as a private in Capt. William Hudson Ballard’s co., Col. Alden’s (sometimes written Brooks’) regiment, joining the company on July 2. The regiment was assigned to the Northern Department and was at Saratoga. James, John and Samuel’s regiments were not involved in the first Saratoga battle but were in the second on Oct. 7, serving as part of Brigadier-General John Nixon’s Brigade under Major-General Benjamin Lincoln. Both the 6th Mass Regiment and the 7th took part in storming Breymann Redoubt (also known as Breymann's Fortified Camp) in that battle. Though the evidence is less clear, James’s younger brother Joseph seems to have enlisted in one of the shorter-term militia units that came to support the right wing at second battle of Saratoga as well. A return of men recruited for US service by Captain Wilbur Hudson Ballard (listed as Nixon’s Brigade, Colonel Alden) specifies that James Emery was killed on Oct. 8, 1777. (There was a clear distinction between men who were “killed” on Oct. 7-8 and others listed as “died” at other times.) Given that the second Saratoga battle took place on Oct. 7, either James was unlucky enough to be involved in late action, or injuries that he received in the fighting the day before proved fatal. He was 21 years old. After serving in the Revolution, James’ brothers John, Samuel, and Joseph and James’ brother-in-law Jonathan Davis (husband of Elizabeth), along with John Emery Sr., moved to Canaan, Maine and farmed near each other. James’ three other sisters married and settled in Maine. Three out of his four sisters’ husbands served in the Revolution. The family became actively involved in their new community, and local histories mention their Revolutionary War service. Back in Acton, when Reverend Woodbury made up his list of Revolutionary War soldiers, he omitted all of the Emerys. Perhaps no one was left in town who remembered them, or perhaps they were no longer considered “Acton,” because John Sr.’s land had become part of the new town of Carlisle in the intervening decades. Whatever happened later, James Emery was born in Acton, was counted as an Acton recruit, and died an Acton resident. Acton should remember his service. Sources Consulted:

By the time local historians tried systematically to document Acton’s Revolutionary War soldiers, quite a bit of time had passed. Rev. James T. Woodbury worked on the project during his pastorate in Acton (1832-1852). We do not know what written sources he had access to, if any. He did talk to townspeople and came up with a list of 181 men who had served in the Revolutionary War. Rev. Woodbury noted at the bottom of the list that he believed it to be incomplete, and research has shown that it was not perfect. (See blog posts on the service of Jonathan Hosmer and his son Jonathan, for example.) Occasionally, we come across a Revolutionary War soldier who lived in Acton and served for the town but somehow eluded Rev. Woodbury’s and later lists. This Memorial Day, we would like to recognize two such men, Isaac Ramsdell and James Emery. Both lived in Acton in the 1770s, were counted for Acton’s enlistment quota during the war, and died in service. Their relatives left Acton in later years, and by the time of Rev. Woodbury’s research, apparently no one was left to tell their stories. Isaac Ramsdell

So far, we have not discovered anything about Isaac Ramsdell’s early life. Complicating research, his surname has numerous variants such as Rams(dall, dill, dale, dle, doll), Ram(dall, dill, del, dle), Ramsden, or Ramsell. The first time Isaac appeared in Acton’s records was a marriage intention, filed in Acton on December 1, 1769, stating that he and Abigail Temple were both residents of Acton. Their marriage, performed by John Cuming Esq., took place in Concord on Dec. 21, 1769. A much later Acton record (difficult handwriting has been transcribed as “James” but seems actually to be Isaac) indicates that Isaac and his wife came to Acton from Concord in 1770. No land records were found for Isaac. Church records, however, tell us that three children of Isaac “Ramsden” and his wife were baptized in Acton in April 1775. Sarah, child of Isaac and Abigail “Ramsdal,” was baptized July 6, 1777. Dorathy Ramsdel, daughter of Isaac and Abigail, was baptized January 14, 1781. Acton records make no mention of Isaac’s death. Despite indications that Isaac may have come to Acton from Concord, we had no success finding Isaac there. Concord vital records make no mention of his birth. We did look for other Ramsdells (or variants) in Concord. A Mary Ramsdil married Ezra Cory in May 1766. Also, Acton records show a marriage between Elener Ramsdal of Concord and Eleazer Sartwell of Acton in 1755. Eleazer and Elener lived in Acton and had many children in the years leading up to the Revolution. If this were a family connection, it could explain why Isaac came to Acton. He may also have had Chelmsford connections; an Isaac Ramsdell owed a poll tax there in 1773. Following up on those potential connections, unfortunately, did not allow us to track down where Isaac came from. We first learned about Isaac Ramsdell’s war service from his widow’s pension application. An Act of July 4, 1836 finally made widows of enlisted men who served in the Revolution eligible to apply for pensions. By that time, many corroborating witnesses would have died or moved to unknown locations, so widows had to provide what information they could. When her pension application was being prepared in late April 1838, Abigail was 91 years and 7 months old. Hannah, eldest child of Isaac and Abigail, made declarations instead of her mother, testifying about what she knew of her father’s service. Though young during the war, she stated that she distinctly recollected “all the material and principal circumstances of her Father’s services and death.” She mentioned that she could “well remember” Capt. Isaac Davis calling her father “before he was up in the morning to go to Concord.” Hannah stated that her father was one of Isaac Davis’s Minute Men and that he participated in the “Battle of Lexington,” as the events of April 19 were known in earlier days, that he immediately enlisted for three years, and that at or before the expiration of his three years’ service, he reenlisted for another three years under Captain Joseph Brown of Acton. She believed that he served at Rhode Island, Ticonderoga and other places, that he was in the battle of Bunker Hill and at the taking of Burgoyne. She remembered his uniform and a fife that he carried in a side pocket. He was home on furlough in December 1779 but returned to active service in the spring. Hannah could “well recollect” the news of father’s death reaching her mother in Acton. Isaac was drowned at “King’s Ferrying Place” in 1780. Some of Hannah Ramsdell’s recollections are surprising, given what we know (or thought we knew). It has been assumed that all members of Isaac Davis’ company are known, unlike those of the Acton militia companies that served on April 19, 1775. Hannah was very young at the beginning of the war and could be forgiven for not remembering accurately. However, her mother would certainly have known who roused her husband that day. It is possible that they lived near Isaac Davis. Assuming that previous lists were correct in excluding Isaac Ramsdell, he probably was in one of the other two militia companies, most likely the “West” company under Capt. Simon Hunt. It is also possible that he went along with the Minute company unofficially, but it is surprising that others did not mention it, given the interest of local historians in that company. At a March 1, 1779 town meeting, article four asked if certain men’s taxes (all in military service at the time, including a very hard-to-read Isaac “Ramsdal”) could be abated for 1776. Whether this had anything to do with military service that year, we cannot tell. (The town dismissed the article.) However, from the records we do have, it would seem that Isaac’s service likely started before 1777. Simon Hunt filed with Col. Eleazer Brooks a listing (dated Acton, Sept. 5, 1777) of men who had been raised from his company to serve in the Continental Army. This indicates that those men had already served with Simon Hunt. Among them was Isaac Ramsdale, engaged for the town of Acton, who joined “Capt. Core’s co.” for three years or the duration of the war. On Feb. 26, 1777, James Barrett, muster master, reported to the State of Massachusetts Bay that he had paid a bounty to certain men since his last report. Among them were five from Captain Cory’s Company in Col. Kise’ Battalion, including Isaac Ramsdell. (The others were Jeremiah Temple, Isaac Russell, Silas Cory and Stephen Cory). Continental Army pay accounts state that Isaac served January 2, 1777 to December 31, 1779 in Capt. Job Whipple’s company of Col. Rufus Putnam’s Regiment and was credited to the town of Acton where he was a resident. Captain Whipple reported on clothing issued to his men in 1777; Isaac received a coat, vest, breeches, shirts, shoes and a hat. He also appears on muster rolls of Capt. Job Whipple’s Company, Col. Putnam’s Regiment, August 5, 1778 (White Plains), Sept. 9, 1778 and Oct. 1, 1779 (at Camp Bedford). Given the dizzying number of reorganizations of the Massachusetts Line during the war, it is not surprising that Isaac’s company membership is confusing. Jeremiah Temple’s records also show him both in Captain Cory’s and Captain Whipple’s companies. Hannah stated that her father served with Captain Joseph Brown. Two 1780 muster rolls from the 15th Massachusetts Regiment commanded by Col. Timothy Bigelow confirm that Isaac Ramsdell was a member of the company of which Joseph Brown was a captain. A muster roll dated July 28, 1780 from Camp Robinson’s Farm (covering the Jan.-June 1780 period) reported that Isaac was “on Command,” presumably doing special duty and not in camp that day. There were many camps in the Hudson Highlands whose exact location was nearly forgotten and had to be researched many years later. Apparently Camp Robinson’s Farm was a large encampment about 1.5 miles east of the Hudson River across from West Point at Garrison, NY. A muster roll taken at Camp “Tenneck” for the month of July 1780 but dated 31 August stated that Isaac Ramsdell died July 28, 1780. A further card in his file states that his service in the 15th Mass. dated from April 1779. He had enlisted for 3 years but died July 28, 1780. It was Hannah’s statement that specified that he drowned at “the King’s Ferrying place.” Kings Ferry was a strategically important crossing point between Verplanck’s Point and Stony Point on the Hudson River. It was the first narrowing point on the river north of New York City. It saw constant use and many historically significant events throughout the war. By October 1779, it was controlled by the Americans. There is no record of what Isaac Ramsdell was doing there while his company was being mustered about twelve miles north at Camp Robinson’s Farm on July 28, 1780. All we know is that something went wrong, and he drowned that day. Isaac Ramsdell left his widow Abigail with 3 small children and another on the way. According to Hannah’s statement and later records, the family consisted of:

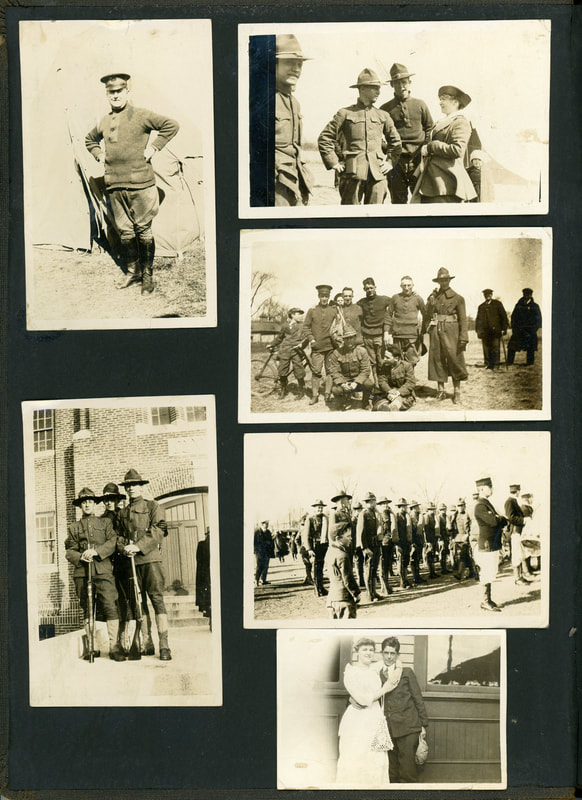

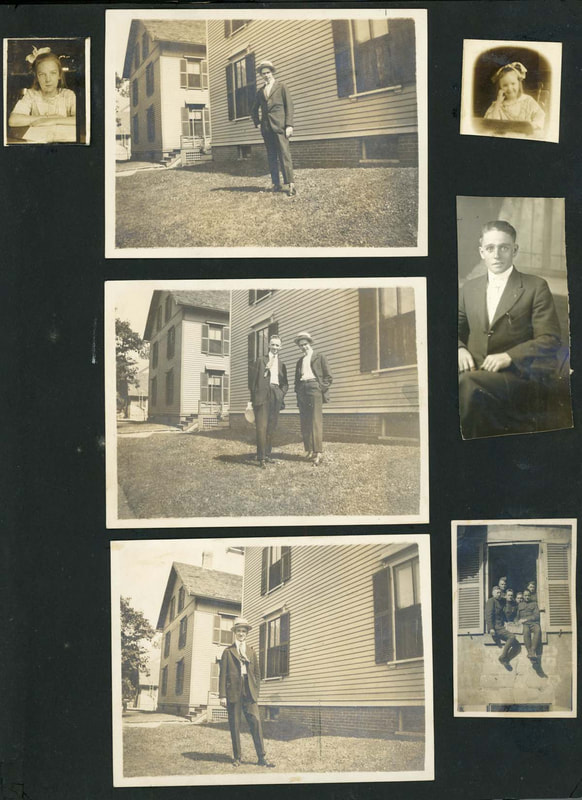

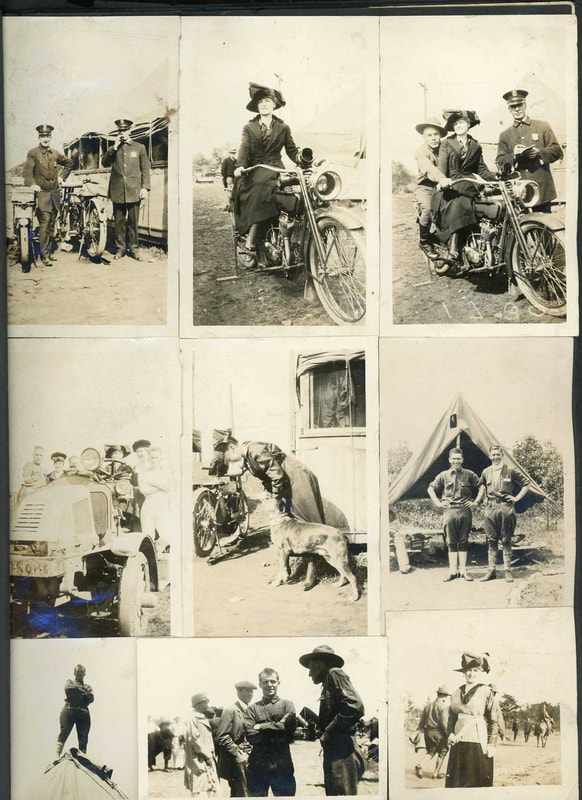

8/8/2023 WW1-Era Photo Album DonatedA donor just brought to Jenks Library a World-War 1 ere photo album that had been in the possession of a member of the Fullonton family of South Acton. No photos in this album are labelled, unfortunately. It is not yet known whose album this was originally, but we were able to put together some clues to help narrow it down. There are many pictures of soldiers in uniform as well as of others, undoubtedly family and friends. Some of the pictures may have been taken earlier. There are only a few clues about where the photos were taken or of whom:

To see more pages, see the full scanned album, available in our Unidentified Photos Section:

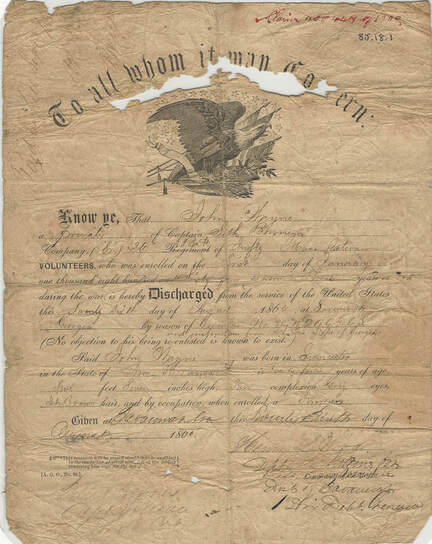

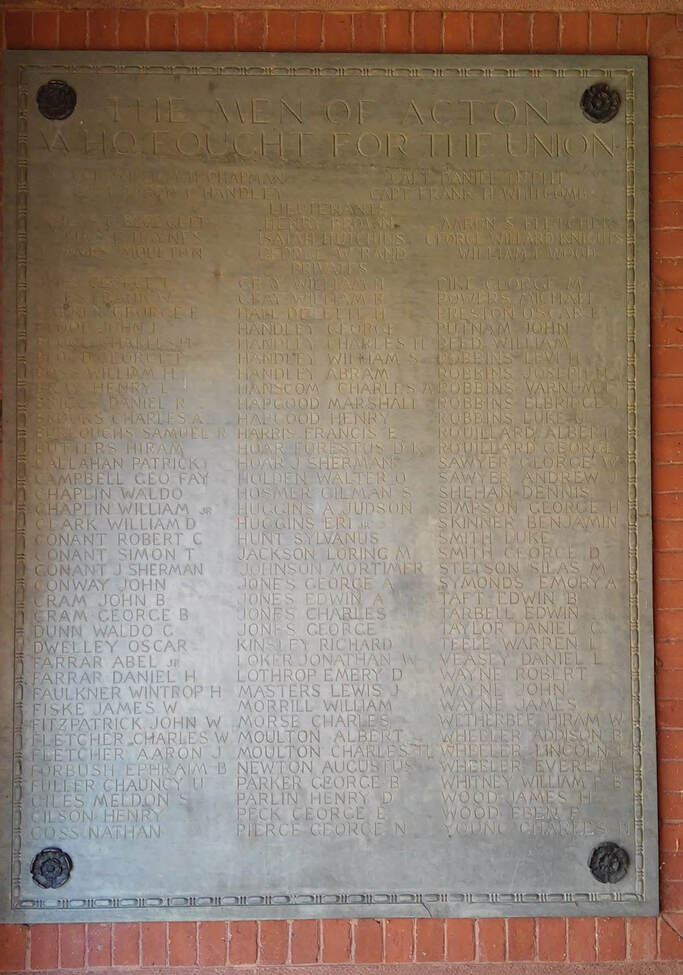

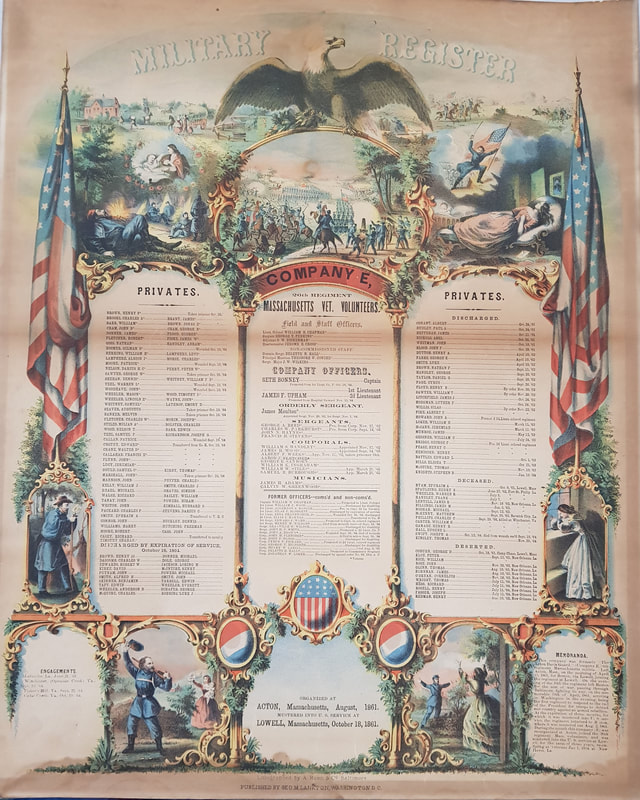

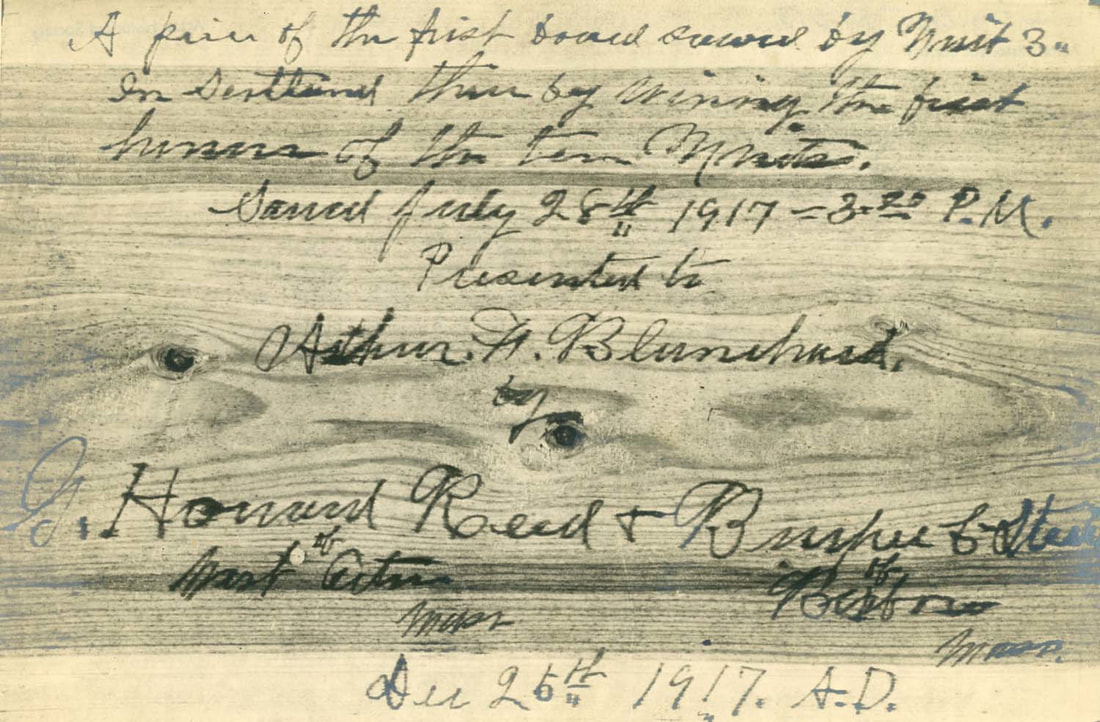

5/2/2022 The Good Idea That Split a Town Soldier suggested to be Samuel Burroughs, Co. E, 26th Reg. Soldier suggested to be Samuel Burroughs, Co. E, 26th Reg. In our previous blog post about the postmaster controversy in 1880s South Acton, we mentioned that one of the underlying factors was probably resentment and distrust related to an ongoing dispute over the payment of bounties to some of Acton’s Civil War veterans. Despite repeated attempts by Acton’s townspeople to pay them, the veterans had never received the money. In 1882, Massachusetts enacted a law (Act of 1882, Chapter 93) that would have authorized the town to make the payment, but a lawsuit by a few influential (and high-income) taxpayers had sought to block it. The course of the controversy was somewhat complicated, but in the long run, to many Actonians, the issue became about more than money. Resentment festered and found outlets in a number of other disputes in the 1880s. The Background Acton sent several companies to the Civil War. The first, Company E, 6th Regiment, went out immediately upon Lincoln’s call for three-month volunteers in April 1861. After the men returned from their service around Baltimore, a company with a three-year enlistment was formed. Company E of the 26th Massachusetts Regiment was organized at Acton in August 1861 and was mustered into service in Lowell on Oct. 18. They were sent first to Ship Island in the Gulf of Mexico and then to Louisiana. Another company went out in August 1862 -May 1863, serving in Virginia, and a 100-day company served July-Oct. 1864 around Washington and on prison-guard duty on an island in Delaware Bay. Both of the latter companies were known as Company E, 6th Regiment. As in previous wars, it was important to the town that it supply soldiers to the cause. Towns were expected to fill a quota based upon population. If they could not fill their quota, they were threatened with a draft. Early in the war, patriotism and idealism were enough to get men to enlist. As the years wore on and the toll of war became more obvious, towns, states, and the federal government started offering financial incentives to induce men to join up. Known as bounties, the payments differed from place to place and over time. Not surprisingly, these disparities caused trouble. A federal bounty of $100 had been offered since early in the war, but it was deferred until the soldier was discharged (honorably). The Militia Act of 1862 required the states to institute a draft if they could not meet their enlistment quotas. In March 1863, Congress passed the Enrollment Act, authorizing a draft system, specifying that all able-bodied male citizens and immigrants who were applying to be citizens from 20 to 45 years of age would, if called, have to serve. Married men 35-45 would be drafted later than the others, and there were a number of exemption categories, mostly on the basis of the needs of family members. Most controversially, people could pay for a substitute to go or, if a substitute was not available, pay $300 to the Secretary of War for one to be found. The Enrollment Act and the ensuing Draft Riots in New York City that summer had pointed to the urgency of getting and keeping men in the ranks. On October 17, 1863, Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 300,000 additional troops, to be raised by the states according to their quotas. Enlistments would be “deducted from the quotas established for the next draft” which, if a state did not make its quota, would begin on the 5th day of January, 1864. The Secretary of War upped the federal bounty, with a premium paid to reenlisting veterans. Meanwhile, Massachusetts was doing its best to fill its overall quota, and its towns were doing the same, offering bounties for enlistment or re-enlistment. Though originally the intention of the bounties was to support a town’s own soldiers, there was certainly an incentive to fill the town’s quota with any soldiers, wherever they could be found. There were some unintended consequences of the system, however. Unscrupulous recruits would sign up, claim a bounty, and never report to camp. These “bounty jumpers” might then sign up elsewhere, possibly under an assumed name, to get another bounty. Other frauds were to sign up and collect a bounty even though the recruit knew that he would eventually be rejected from serving (because of a disability or signing up underage, for example). A more basic problem with the system was that towns that could afford to pay large bounties were more likely to fill up their quotas than towns in greater financial difficulty. Disparities of bounties and the substitute exception yielded the impression that the rich were able to avoid the worst consequences of the war while the poor fought. Some of those who hired the substitutes, considering it a financial transaction, felt that they had the right to be reimbursed for their substitute payment. Some were of the opinion that those who went as substitutes, because they were paid to go in place of a drafted man, did not deserve the bounty for going to war. The divide between the poor, whom some judged for enlisting for the money offered, and the rich, who could afford to pay for a substitute, grew. There is no doubt that some bitterness that festered in Acton after the war was due to this economic divide. To try to introduce more equity into the system and to deal with some of the bounty-jumping problems, Massachusetts’ legislature passed a number of laws. In fairness to all parties in Acton’s bounty dispute, even with the benefit today of being able to read the digitized laws of the Commonwealth, the bounty laws make confusing reading. It must have been quite hard to keep up with them in the early 1860s, during a war, and especially in places with poor communication. Practice did not necessarily follow the intentions of the lawmakers. One of those intentions seems to have been that local bounties would stop, although towns seem to have interpreted the laws as limiting local bounties, not eliminating them (See Chapter 91, approved March 1863). A law passed in a special session in November 1863 (Chapter 254), set a uniform Massachusetts bounty at $325 for those who enlisted for three years. Though well-intentioned, the new law did not solve the problems. Rightly or wrongly, a number of towns’ representatives continued promising what they believed to be the maximum local bounty allowed at the time for the reenlistment of serving soldiers, $125. Acton’s Veterans Reenlist Acton’s bounty controversy centered on the soldiers of the 26th Regiment who had been sent to Louisiana in 1861 and served there through the beginning of 1864. During the company’s early service, the most harm came to the soldiers through disease. In June, 1863, the Regiment saw action at LaFourche Crossing and later made an attempt to take Sabine Pass. In the fall of 1863, it went to Opelousas and New Iberia, Louisiana. A November 27, 1863 letter from Delette Hall to his cousin Henry Hapgood (who had returned from the nine-month company sick) said: New Iberia is quite a villiage. About 50 miles from Breashear City on Bayou Teche River. This is quite a muddy place in wet weather We have to ditch the ground to keep from being drowned out Yesterday was Thanksgiving Day. but was not observed here except by issuing a ration of whiskey to the men. I thought of you all & if I was not there my mind was. I was on Picket & had a piece of salt pork & some hard tack for dinner. Well that was a little better than I had two years ago in Boston harbor. & next year I hope I shall be at home. We shall soon be nine months men our term expires the 18th Oct 186[4] which day we were mustered into the U. S. Service. It seems a long time to look ahead. I hope the rebs will get enough before the year is out. Clearly at that point, Delette Hall and his compatriots were not thinking of reenlisting. At the end of 1863, the Union army needed to keep seasoned men in its ranks. Experience showed that raw recruits were more likely to desert. The hope was that reenlisting soldiers would be inured to camp conditions, be willing to follow orders, and stay. Men who were acclimated to conditions in the South would have been considered an asset to the 26th Regiment. To understand what happened to spark the bounty dispute, we have to rely on testimony given much later. A two-sided supplement printed by the Acton Patriot laid out all that was said at a hearing before the Legislative Committee on Military Affairs, January 26, 1882 (in the Society’s collection and also transcribed by Brewster Conant). By the time one has read through the claims and counterclaims, one is hard-pressed to know what really happened. There were contradictions, inconsistencies over time, fading memories, and the influence of “circulars” and petitions on people’s interpretation of events (operating like the social media of the time). Also, by 1882, the needs of the war were long past, whereas the pinch of tax bills was a present problem. Though it is impossible to be completely sure of who knew what and when they knew it, most people in the post-war period seem to have agreed upon a few points. Acton’s Captain William H. Chapman, veteran of the 3-month original Acton Co. E, 6th Regiment and by late 1863 the Captain of Co. E, 26th Regiment, was also serving as the recruiting officer of the 26th Regiment. He was aware of the need for trained soldiers and of competition from other Massachusetts communities that he believed were offering local bounties to soldiers to re-enlist, with the quota credit going to those towns. Concerned that Acton would lose its soldiers to other towns offering financial incentives, Capt. Chapman told the men of the Acton company that Acton would “do as well by them as any other town” if they would reenlist to the credit of Acton. The going bounty rate at that point seems to have been $125. In later years, few disputed that the soldiers reenlisted in early 1864 in the 26th Regiment, for 3 years or the duration of the war, believing the promise that Acton would pay them a bounty of $125. Few disputed that Captain Chapman made the promise. The original dispute centered on whether or not he had been justified in making the promise and whether the town had the legal (or moral) obligation to keep it. Part of the problem with the later bounty dispute is that people were looking back many years and judging based upon subsequent events. At the time that Capt. Chapman was recruiting, the Regiment was in New Iberia, Louisiana. According to his later testimony, the mails were sporadic and it was not feasible to send messages to Acton by telegram. One can see how the captain might have felt that he needed to make decisions on the spot. Back home in Acton, however, there was a recruiting committee who felt that they should be the ones making decisions, particularly with respect to how the town’s money was spent. They also were more likely to have had a chance to read the laws passed by the legislature. The recruiting committee denied having authorized the bounties in advance and claims were made that no one knew about the bounty promise, but Luther Conant, longtime moderator, remembered that the issue was discussed at the 1864 town meeting. The war went on. After much of Company E reenlisted, the 26th Regiment was sent to Virginia where the company moved into action at Winchester (Opequon Creek) on Sept. 19, 1864, Fisher’s Hill on Sept. 22, and Cedar Creek on October 19. The company had lost a number of men to disease and also lost five men as a result of the fighting at Winchester, including Delette Hall's brother Eugene. Some were injured, including Captain Chapman, who managed to survive a gunshot wound to the head. The Company stayed around Winchester through May 1865. They spent a month in Washington, D. C., then were sent to Savannah. They were discharged in September 1865. Undoubtedly the men expected that when all was said and done, they would be paid their promised bounties. During the war, the town had paid some recruits bounties. The 38 members of the nine-month company recruited in the fall of 1862 received $100, with an additional $25 for the 23 recruits “called for from this town on the first quota” who signed up for three years. The town voted in December of that year that if it were required to supply more men, the recruiting committee was authorized to offer the same bounty to any who enlisted or were drafted. The 1862-1863 town report listed every man in service and whether or not he had received a bounty payment from the town. (The state seems to have retroactively reimbursed the $100 bounties paid to the 1862 recruits.) In November 1863, the town voted that the Selectmen plus three additional Recruiting Committee members would have discretionary powers regarding bounties. In November 1864, the town voted that their recruiting committee should investigate the claims of the town’s serving soldiers and those who had returned home and that the town should raise $5,500 to recruit men for the war. Given all of that, it does not sound unreasonable for Capt. Chapman to have thought that the town would back his claim that the town would do as well by its men as other towns were doing. However, the war ended, (most of) the veterans came home, and the claim had never been paid. The War’s Aftermath At the March 1866 town meeting, Acton debated paying those soldiers who enlisted in 1861 and reenlisted in 1864 the same bounty that had been paid to soldiers who enlisted later and served in the US service for less time. The town decided to postpone any action until the state and federal governments had taken action on bounties. According to Phalen’s history of Acton, “As things later developed this proved to be an unwise decision but at that time nobody could have foreseen that by this action the town planted the seeds for its most vicious and prolonged local battle.” (p. 197) Though this fact was not usually mentioned in the Acton fight, bounty claims took up a great deal of energy on the part of both state and national committees in the post-war years. The Massachusetts Legislature’s Committee on Military Affairs dealt with petitions of many towns, including petitions from Acton in three different sessions. Acton voted to pay soldiers’ back bounties in 1872 and petitioned to be able to pay it. In early 1881, the Committee heard petitions, not only from Acton, but also from Wilmington, Stoneham, East Bridgewater, Andover, and Natick, all rejected. Acton’s petition went nowhere until the third time it was presented in early 1882. In March 1882, the House passed a bill that would allow Acton to raise up to $4,000 to pay $125 to each of the veterans who had reenlisted in the 26th Regiment under the call of the president dated Oct. 17, 1863, were credited to Acton, and were never paid. The bounty could be paid to the soldier’s heirs if he had died. In response, at town meeting on April 3 1882, the town of Acton voted to pay the bounties, but the measure passed by only four votes (219 to 215). By this point, the controversy had split the town down the middle, apparently even at town meeting where Phalen wrote that “The glowering partisans congregated on either side of the center aisle.” (p. 231) Town meeting records mention that “it was voted to have the area in front and on each side of the Desk kept clear so that voters need not be obstructed in approaching the Polls.” Whether this was because of hostility or because it was Acton’s largest town meeting ever is not clear. After the vote, a cannon was shot off in South Acton in celebration (Acton Patriot, Apr. 6, 1882, p. 1) However, as often happened in Acton politics, a vote taken was not seen as final, but only as an opportunity to reconsider. Two town meetings followed. Both sides undoubtedly tried to sway opinions and get out the vote. The Acton Patriot’s Concord Junction reporter mentioned on Sept. 7, 1882 that “Thomas Clifford was earnestly sought for early Saturday morning by one of Acton’s heavy taxpayers. His object was to secure his vote against paying the soldiers’ bounty.” Probably the same heavy taxpayer “offered to bet $100 with any live men that the soldiers get beat.” (page 1) These efforts did not change the outcome, however. On August 21, an attempt to overturn the vote failed by 204 to 194, and on Sept. 2, the anti-bounty side lost again by 206 to 198. Phalen’s history of the town of Acton seems to indicate that the resolution of the bounty issue happened in 1882 with the Senate and House overriding the governor’s veto. “Thus ended the great bounty fight beside which all other Acton rows seem rather tame. The payments were made with reasonable promptness with one exception...” (p. 233). Searching Acton’s town reports did not yield a record of those payments; in fact, the bounty tax seems to have been assessed, held onto, and then without explanation refunded by the town. The reason was legal wrangling that went on much longer than is mentioned by Phalen. Not able to swing the vote in their favor, the opponents served an injunction on the town to prevent payment and hired Judge E. Rockwood Hoar as their counsel. According to newspapers of the time and legal synopses, the opposition’s case made its way through the legal system and was heard by the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts in early 1885. The case hinged on the constitutionality of the 1882 act of the Legislature (chapter 93) that authorized the town to raise taxes to pay the bounties. According to the Supreme Judicial Court’s ruling, the town of Acton never promised to pay a bounty, did not (directly) receive the men’s services as soldiers, and was not responsible for paying them compensation. Therefore, it had no debt to them. Any payment made so long after the fact would be akin to a gift of gratitude to private individuals rather than payment of a debt for a public purpose (as inducing enlistments would have been). Taxes must serve a public, not private, purpose, and therefore, the 1882 law allowing Acton to raise taxes to pay the veterans of the 26th Regiment was unconstitutional. The bounty opponents must have thought that the matter would end there, but the dispute had gone too far by that time. By March, 1887, the town of Acton was petitioning the state to pay the bounties, because Acton was barred from raising the money itself. (Boston Journal, March 11, 1887, p. 1) Both sides testified again. The Society owns a copy of the opposition’s testimony that started with the statement that they were aware that they were “opposing the claim of the men, who, in a critical time in our history, rendered with such distinguished services to the country that it seems almost like robbery, - unpatriotic at least, to withhold from them anything in the way of pensions or gratuities that they may demand.” The opponents followed up, however, by saying that the Commonwealth owed the men nothing because this was a town matter. (Of course, the town previously had been kept from paying the claim by this group’s lawsuit.) The testimony ended with “We would respectfully ask, therefore, that you, as guardians of the public treasury against unfounded claims” would find against the town of Acton. The Society also owns a copy of the proponents’ testimony. The testimony mostly reiterated points made before, although it does contain a paragraph of personal attack on the opponents; the sides were portrayed as humble veterans versus the rich. At any rate, the Senate Committee on Claims reported favorably on the town’s petition. (Boston Journal, April 15, 1887, p. 3) In May, the Committee on the Judiciary ruled that the Legislature has the right to appropriate and pay money to individuals, even if it could be portrayed as a gratuity, if there were “some equitable ground upon which such payment ought to be paid.” (Boston Journal, May 5, 1887, p. 2) The legislative debate on the measure was reported in June, 1887. Some cited fear of opening the floodgates to other, similar claims. However, the majority, including Mr. Conant of Acton, felt that the resolve was an “act of justice.” (Boston Journal, June 8, 1887) Finally, the joint Resolve of 1887, Chapter 106 ordered that $125 was to be paid by the Commonwealth to the 31 soldiers (or their legal heirs) of the 26th Regiment who had reenlisted and never received the bounty they were expecting. The governor had objected to the Resolve, but the Senate and House of Representatives passed it over the Governor’s objections on June 16, 1887. The fight was finally over. The veterans got their bounties and apparently it was the people of Massachusetts as a whole who made good on the promise, rather than the people of Acton who had voted repeatedly to pay it. It is clear that a dispute allowed to fester for over 20 years was extremely harmful for the town. Putting off dealing with the problem in the hope that it would conveniently disappear led to infinitely more trouble later. As the bounty dispute dragged on, campaigns for support, including assumptions, exaggerations, and character slurs, led to increasing polarization. Both sides’ attitudes seem to have hardened into a belief that they were fighting for the “right.” Newspapers elsewhere noted Acton’s contentiousness with comments such as “Acton folks are still squabbling...” (Springfield Republican, Aug. 19, 1882, p. 6) What becomes most apparent is that the bounty dispute reflected divisions in society. On the one hand were those trying to prevent payment. They portrayed the veterans asking for bounties as greedy opportunists who had not received a legitimate (or perhaps any) promise of payment before they reenlisted and who were trying to take hard-earned tax money from Acton’s struggling farmers and from families of veterans who had not received a bounty. Those supporting the bounties believed that the town should make good on the promise. They portrayed the men against the bounties not as struggling farmers, but as rich taxpayers who were too stingy to pay the money that had been promised to men who risked their lives in the war. Underneath the accusations were basic issues, especially about who has the right to run the town. Should it be the influential, well-to-do men who had served (and controlled) the town for many years, or less-wealthy men who perhaps moved about looking for opportunity? The committee at home during the war had been either elected or appointed and felt they had the right and the duty to act for the town and decide how to spend its money. Those who were far away in the field at the time felt justified in recruiting for the town. The fact that there was some justification for both sides’ viewpoints made the divisions much more entrenched. As is often the case, after all of the conflict that was reported in the newspapers of the day, the actual resolution and payment of the bounties was apparently done without much fanfare. Though it is likely that the participants remembered the vitriol involved in the dispute, life moved on. Three years later, Acton had a Memorial Library honoring its veterans’ service. Acton’s veterans of the 26th Regiment (and of the bounty fight) were proudly listed at the entrance of the new Library. References:

One of our ongoing projects has been to research the stories of early residents of Acton who were Black or of mixed-race ancestry. The Massachusetts Tax Inventory of 1771 revealed that there were two “servants for life” in Acton at the time, including one person assessed to Simon Tuttle. (For relevant entries click here.) There was no detail about who the person was. It was easy to assume that records from the March 4, 1783 town meeting referred to the same person when Acton voted to pay Mr. Simon Tuttle for “the Bounty for his negro man which was Twenty four Pounds in March 1777 to be Paid by the Scale of Depreciation.” However, as is so often the case when we try to understand events more than two centuries ago, we have to be careful with our assumptions. In early 1777, the Continental Army was in a recruiting crisis after enlistments ran out at the end of 1776. There was pressure on towns to fill their quota of soldiers. At the March 10, 1777 town meeting, Acton approved a bounty of twenty pounds to every man who would enlist in the Continental Army for three years or as long as the war lasted. An additional four pounds was offered to men who had or would volunteer between March 3 and March 17, 1777. Bounties obviously cost money that had to be raised through taxes. To understand each taxable person’s contribution to the war effort, the town chose a committee to determine “what Service has been Don[e] Personally or by Hireing men to go into the Service ever Since this Present war Begun.” One of the members of that committee was Simon Tuttle. In trying to fulfill quotas for towns, it was apparently common practice for recruiters to pay bounties for enlistment out of their own pockets on the understanding that they would be reimbursed. At a July 30, 1778 town meeting, it had been proposed that the War Rates (taxes) of four men including Lt. Simon Tuttle be abated, presumably for their recruiting efforts. That proposal was voted down; instead, the town voted that “Every man in the Town that had Paid money to hire men for the Town into the Continental army for three years Shall Receive Said money from the Town.” During the war years, assessments were frequently revised, and the town did not always have the cash to pay soldiers or recruiters what they were owed. Inflation was so great that delays in payment made previously-promised amounts seem worthless, so by the time Acton actually paid, amounts had to be adjusted ”by the Scale of Depreciation.” Most of the men who were hired and received bounties from the town of Acton were not mentioned in town meeting records. At the March 4, 1783 meeting, however, two individuals were identified. The third agenda item at the meeting resulted in the formation of a committee “to Settle with Capt Joseph Robbins Respecting his Bounty that he Paid to Oliver Emerson.” The fourth agenda item resulted in a vote to pay Simon Tuttle the bounty for “his” man. The use of the word “his” may look to modern readers as if the soldier either had been enslaved or was an employee. However, we discovered another town meeting record that called that assumption into question. At the March 5, 1781 town meeting, a committee (including Simon Tuttle) was formed to help the assessors to “class” the residents for the purpose of hiring soldiers to fulfill the town’s quota. The record went on: “...also voted that if any Class in this Town Shall be So unfortunate as not to Procure their man (after ofering their Best Endeavors to hire one) that they Shall not be Subject to Pay any more than their Proportion of the fine and the Charges that the Several Classes are Put to in hireing and Pay their men in this Town” (emphasis added) Given the above phrasing, it is possible that the 1783 town meeting record’s use of “his” man meant only that the soldier had been hired by Samuel Tuttle to fill a quota. Town meeting records do not tell us for certain. What we can say, after our research, is that whatever the soldier’s route to military service for the town of Acton, his story did not have a happy ending. Finding out more about Simon Tuttle’s “man” was complicated by uncertainty about his name and pre-war experiences. We did discover that Rev. James T. Woodbury’s mid-1800s listing of known Acton Revolutionary War soldiers (transcribed in town histories by Fletcher and Phalen) included “Titus Hayward, colored man, hired by Simon Tuttle.” The compendium Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War (MSSRW) did not have an entry for a soldier of that name. Thinking that perhaps he might have been a (possibly former) slave who enlisted under the name of Tuttle, we found a Titus Tuttle from Acton in MSSRW as having enlisted April 29, 1775 for 3 months and 10 days. Other service was shown for a Titus Tuttle (no town and no description) in 1776 (2 months) and 1781 (21 months). (There were other entries of individuals named “Titus” with no surnames in MSSRW, one from Harvard and one from Pittsfield.) None of the service terms for Titus Tuttle or Titus __ matched the March 1777 enlistment for which Simon Tuttle was later paid a bounty. Matching up the service dates and investigating surname variations for Titus “Hayward” led us to the record of Titus Haywood. His service record (available online and summarized in MSSRW) shows that he enlisted on March 14, 1777 and served in Edmund Munroe’s Company, Mass. 15th Regiment under Col. Timothy Bigelow. Captain Munroe was from Lexington as were many members of his company. The remainder came from other Middlesex County towns, including Acton men John and Theodore Barker and Titus Haywood. (MSSRW cited a return dated Feb. 2, 1778 that gave Titus Haywood’s residence as Acton and his enlistment credited to fill Acton’s quota.) Included in the company were at least five other soldiers who have been identified as people of color. The company served in the Northern Department and fought at Saratoga. Titus Haywood apparently was not able to participate in the actual Saratoga campaign. By September 1, 1777, he was reported as being sick in the hospital, later was reported as sick at Albany where there was a large military hospital, and finally in April 1778 was reported as having died on Nov. 5, 1777. Astoundingly, though later town records and histories listed Titus “Hayward” as a soldier, mentioned his race, and specified who was paid for his enlistment bounty, nowhere in town records did we find a mention of the fact that he died while in service. It is a reminder of how “history” comes to us. In later years, there was much more interest in soldiers who died in battle and in the Actonians who were “first at the Concord bridge.” Other stories disappeared over time. Many questions remain unanswered. Who was Titus Haywood/Hayward? While some have guessed that the man Simon Tuttle hired might have been his slave originally, that hypothesis may be incorrect. We had thought that perhaps the Titus Tuttle who served from Acton in the Revolution might be the same person as Titus “Hayward” in the Woodbury list, but we have not yet found any evidence confirming that theory. We found some Titus Tuttles alive after the war. Clearly those individuals were not the Titus Haywood who died in 1777. We did find one record for a Titus Haywood that may be the same person. An entry in MSSRW for a Titus Haywood (no town given) shows him as a private in Captain John Hartwell’s co., Col Dike’s regiment. He enlisted Dec. 14, 1776 and was credited to the town of Concord. The regiment served until March 1, 1777. He would have been available to reenlist on March 14, 1777 and be credited to Acton, which would have made him eligible for the 24-pound bounty from the town. We hope that he actually received it. Town records do not indicate why it took a special town vote for Simon Tuttle to be paid for hiring him. So far, we have not discovered the story of Titus Haywood’s earlier life. Our search for information will continue, but on this Memorial Day, we honor the memory of Titus Haywood who served for the town of Acton and never made it back.

Samuel’s family connections made it highly likely that Samuel also served in the Revolution. Samuel’s brothers Asa and Nathan and many of their relatives served. Samuel also had many soldiers in his family on his wife’s side; she was Lucy Davis, first cousin to Captain Isaac Davis who led the Acton minutemen and fell at Concord’s North Bridge. We checked our standard town histories by Fletcher and Phalen, both of which reprinted Rev. James T. Woodbury’s listing of Actonians who were known (at the time the list was created, sometime in the mid-1800s) to have served in the Revolution. The list is not perfect, and Rev. Woodbury acknowledged at the time that it was incomplete. However, Samuel Parlin did appear in that listing. Some of his children and other relatives living in Acton were the likely sources. Our next challenge was to try to determine when Samuel actually served. Fortunately, our quest was made much easier when we were able to turn to the Robbins papers in our own archives. Not every man who served is listed there either, but for lucky people researching certain individuals, the papers can be a goldmine. It happens that Samuel Parlin was listed as one of the Actonians who signed up on September 29, 1774, “thinking our Selves Ignorant in the Military Art and Willing to be Instructed” by Captain Joseph Robbins in a militia company. Later, Captain Robbins documented the fact that Samuel Parlin had served under him in 1776 (as did his brothers Nathan and Asa). We also discovered that much later, Concord’s Gazette and Yeoman listed those who were living in Acton in April 1824 who had fought at Concord on April 19, 1775. Samuel Parlin was included. (April 24, 1824, p. 2) Having confirmed that Samuel Parlin did indeed serve in the Revolutionary War, we set out to learn about the rest of his life. Samuel was born in Acton on May 18, 1747 to Jonathan Parlin and Sarah Warner. His family were among of the original residents of Acton when it became a town in 1735. They lived in the northern part of Acton (previously Concord) that eventually became Carlisle. A map of historic home sites done by Donald Lapham in 1969 shows that the Jonathan Parlin house was located at 322 West Street (at the corner of Acton Street) in present-day Carlisle. According to The Descendants of Nicholas Parlin, Samuel had numerous siblings, the oldest of whom (Jonathan) died as a soldier in the French and Indian War in 1758. The book lists two brothers (Nathan and Asa) serving in the Revolution and, with some question, an additional soldier brother Nathaniel. Aside from a muster and payroll record indicating that “Nathaniel” Parlin marched from Acton to Roxbury on March 4, 1776 and served six days, we could find no vital or other records for a man of that name. It is very likely that the record was actually Nathan’s. Samuel had a sister Elizabeth who never married, and as the Parlin genealogy added, unhelpfully, “There were four other children, all girls.” (p. 22). We were able to find in Acton’s vital records that Samuel had three additional sisters, Sarah, Lucy, and Mary. Sarah died in 1759. Acton death records do not mention Lucy and Mary, but they must have died before their father, as his probate record does not list them as survivors. (It also does not list a son Nathaniel.) Samuel’s father Jonathan died in 1767. His estate included an 87-acre farm, partly in Acton and partly in Westford, bordering on the land of John Heald Jr. The farm was left 1/3 to Samuel’s mother, as was customary, and 2/3 to the eldest surviving brother Nathan who lived out his life in Carlisle. Asa eventually farmed nearby and served the town of Carlisle for many years as town clerk and selectman. Samuel Parlin, however, moved to a part of town that remained Acton. On March 26, 1772, he married Lucy Davis (1749-1829), daughter of John and Sarah (Flint) Davis of Acton. Samuel and Lucy had eight children:

We know that Samuel Parlin lived at what would now be 48 Hammond Street. The house, which stood until a tragic fire in 1985, was believed to have been built approximately 1772 -1776, presumably based on the date of Samuel’s marriage to Lucy Davis. Supporting that estimate, we found that in the tax valuation of 1771, Samuel was listed without taxable property, but in Lucy’s father’s 1778 probate record, Samuel Parlin was already a landowner. Lucy inherited eight acres of pasture and woodland, known as part of the “Proctor Place” that bordered land of “Samuel Parling.” The probate record also noted that Lucy’s father had previously given her 86 pounds, 19 shillings and 9 pence, probably the value of land John gave to Lucy and Samuel as they started their life together. Lucy inherited an additional thirty-acre lot on the “westerly side of Nagog Hill” when her eldest brother John died in an accident on March 2, 1791. The lot was bounded by land that had been set off to her sister Abigail Conant and by land of Simon Tuttle and Samuel Jones Jr. Samuel first appears in Acton’s town meeting records as a fence viewer in 1776. He was clearly back from military service in 1780 because he was chosen selectman and assessor in that year. Starting in 1783, he was chosen regularly for roles such as constable, tithing man, assessor, surveyor of timbers or highways, and school committee. He was also selected as a member of special committees, for example to deal with abatements to individuals’ taxes and to deal with the selectmen about town expenditures. He was made a member of the committee to instruct the Convention at Concord in Oct. 1786 (probably the Middlesex County convention dealing with issues that led to Shay’s Rebellion). In May 1798, town meeting records show that he was selected for a special committee “In a Constitutional mannar to take under Consideration the alarming Situation of our publick affairs and express there minds thereon the Town Expressed there minds agreeable to this article and Chose Jonas Brooks John Edwards Jonas Heald Samuel Parling and Thomas Noys a Committee to publish the Same.” (This was probably related to tricky diplomatic issues with France.) It is clear that Samuel Parlin was a trusted figure in town, someone who could handle both money and negotiations amid controversy. According to church records, on Nov. 24, 1791, Samuel Parlin was chosen for the office of Deacon of the First Parish church of Acton. On April 19, 1792, the record continued that Samuel Parlin having declined, the church chose Simon Hunt who accepted and “took the seat” in August. While the Parlin genealogy refers to him as “Deacon Samuel,” there is no record that Samuel Parlin actually ever “took the seat” himself. The story of why he declined the honor never made it to the history books.  Samuel Parlin died on March 7, 1827, leaving his widow Lucy and four surviving children. At the time of his death, his real estate included the home farm containing 38 acres of land, a 5-acre “Sargent Meadow”, a 6-acre “Chaffin Meadow”, and an 11-acre “Littleton Pasture.” He also had the title to pew number 42 on the lower floor of the Acton Meeting house. Among his personal belongings were agricultural products and tools, cows, swine, sheep, and, oddly, ½ of a horse. Samuel’s widow Lucy survived him by two years, and eldest son Jonathan only by three. The home farm passed to son Davis in 1831. The house eventually went out of the family to Thomas Hammond whose name was given to the road on which they lived. When some of the land was developed in the late 1960s, the new road was given the name of Samuel Parlin Drive. Our research into Samuel Parlin reminded us of a few lessons that are worth repeating. Despite having found what looked like a very complete genealogy of the Parlin family, if we had not checked each item, we would have believed that Samuel had an additional brother named Nathaniel and that Samuel’s son Samuel Jr. lived to adulthood and married a woman named Phoebe. If we had only paid attention to the flag holder in Woodlawn Cemetery, we would have thought that Samuel’s military service was in the War of 1812, not the Revolution. And if we had stopped our searching at Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, we would have missed Samuel’s service, the best documentation of which, ironically, is in our own archives. Some Sources Consulted:

7/24/2020 Acton's Early Black ResidentsGaining an understanding of a town’s history is complicated by the fact that some residents’ stories are much less accessible than others. Standard town histories from the nineteenth and early twentieth century tended to focus on a small group of socially prominent citizens. People of color were seldom mentioned. Anyone trying to learn about the early Black residents of Acton has had very little material to work with. Records are sparse, and there are sometimes conflicts among the pieces of information that we do have. To better understand early Acton’s racial diversity, we set out to find all mentions of Black and mixed-race residents (slave or free) in Acton’s early records. To do that, we used eighteenth- and nineteenth-century documents that sometimes refer to racial diversity with terms that we would not use today. When quoted here, it is only to give accurate historical evidence about a person’s racial background. There is much work left to do, but in collaboration with the Robbins House in Concord, we offer what we have learned so far. We will start in 1735 when Acton was set off as a town from Concord. We are hampered by lack of census records in the early days but will continue to look for more information. We do have a definitive record that slavery existed in Acton after it became a town. The 1754 Massachusetts slave census completed by the Selectmen stated that there was “but one male Negro slave Sixteen years old in Acton and No females.” (The inventory asked for the number of slaves over the age of sixteen; the wording presumably meant that the male mentioned was in that category, rather than being exactly sixteen years old.) We have no way of knowing if there were any younger slaves. Unfortunately, the inventory did not list either the name of the slave or the slave owner. As a result, we have no idea whether he was eventually freed and whether he stayed in town or moved on to another location. Acton apparently also had free Black and/or mixed-race residents during its earliest years. We are still trying to document their stories. In South Acton by 1731, there was a William Cutting who, according to a story in a published journal of Rev. William Bentley, (volume 2, page 148) was himself or descended from a “Mulatto” slave who “upon the death of his master, accepted some wild land, which he cultivated & upon which his descendants live in independence.” (This story is still being researched; our various efforts to confirm those details have not yet been successful. A 1731 deed from Elnathan Jones to William Cutting is extremely hard to read, but it mentions a purchase price paid to a living person, rather than a gift or inheritance. Another 1732 deed from Elnathan Jones also seems to be a straight sale. Probate records have not yielded clues, either. A possibility is that the story was about an earlier ancestor in a location other than Acton.) An Acton’s Selectmen’s report dated Feb. 2, 1753 mentions a road being laid out, with one of the boundaries being “a Grey oke on Ceser Freemans Land.” Both Cesar and Freeman were names associated with free African Americans of the period. Cesar Freeman’s story is unknown at this point, so we do not know if other Freemans in town records are his relatives. Harvard University has put online a transcribed and indexed version of the Massachusetts Tax Inventory of 1771. This inventory reported the number of each taxpayer’s “servants for life.” According to that database, there were two “servants for life” in Acton, assessed to Amos Prescott and Simon Tuttle. (For relevant entries click here.) We know nothing about the person assessed to Prescott. However, it appears that Simon Tuttle’s “man” fought in the Revolution. At town meeting on March 4, 1783, the town voted to reimburse Mr. Simon Tuttle for “the Bounty for his negro man which was Twenty four Pounds in March 1777 to be Paid by the Scale of Depreciation.” Simon Tuttle was one of the Acton leaders who was charged with recruiting men to enlist from Acton, and it was common practice for the recruiters to pay bounties for enlistment out of their own pockets on the understanding that they would be reimbursed. (Acton took such a long time about actually paying the men back that the value of currency completely changed and adjustments needed to be made “by the Scale of Depreciation.”) The unique thing about this 1783 entry in town records is that the recruit was described at all, in particular his race and the fact that he was considered Simon Tuttle’s man. We have a clue as to his name; Rev. Woodbury's list of known Revolutionary War soldiers from Acton (compiled in the mid-1800s) included the entry "Titus Hayward, colored man, hired by Simon Tuttle." For more information about this soldier, see our blog post about our research into his identity. Acton did have a free Black population in the years of and following the Revolution. John Oliver, listed in later census records (inconsistently) as a free person of color, enlisted for Revolutionary war service from Acton as early as April 1775. John Oliver lived in North Acton in an area near the town’s borders with Westford and Littleton. We are investigating whether there was a community of Black and mixed-race residents in that area. What we know about John’s life in particular was discussed in a previous blog post, and the location of his farm was discussed in another. Another Black Revolutionary War soldier with Acton ties was Caesar Thomson who appeared in Acton’s records after the war. According to an article published by the Historical, Natural History and Library Society of South Natick in 1884 (page 100), Cesar Thompson was a slave of Samuel Welles, Jr., a Boston merchant and the largest landowner in Natick by the time of the Revolution. When Natick needed men to fill its quota of soldiers, Mr. Welles sent Cesar, whose Revolutionary War service was extensive. (See Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, Volume 15, pages 631 and 668). After serving for several years, he was “disabled by a rupture” and was actually granted a pension in January 1783. (Pensions were granted to disabled soldiers, though full pension coverage for veterans was far in the future. Unfortunately, the earliest Revolutionary War pension records were lost in a fire.) As stated in the 1884 article, Natick town records contain the following notation: “Boston, Feb. 18, 1783. This may certify, to all whom it may concern, that I this day, fully and freely give to Caesar Thompson his freedom. Witness my hand, Samuel Welles. A true copy. Attest, Abijah Stratton, Town Clerk.” After the war, free man Cesar Thompson lived in Acton. At the April 5, 1783 town meeting, a committee was appointed to figure out seating for the meeting house (a regular occurrence). Seating arrangements were to take into consideration age and property, using the prior two years’ tax valuations. It was voted that the committee was to “Seat the negros in the hind Seats in the Side gallery.” Clearly, despite years of fighting for political freedom and equality of “all people,” Acton was not ready to grant equality to all of its own people. (It should be noted that it was an era in which citizens paid for pews in the meetinghouse, which was not only a church, but the place were town meetings took place. Presumably, pew placement denoted social status.) In an 1835 centennial speech, Josiah Adams recounted a childhood memory that reveals how it must have felt to be one of very few people of color in the town at the time. Young Adams would watch as Quartus Hosmer climbed the stairs to the “hind seat” of the gallery, eagerly waiting for him to reappear with his queue of “graceful curls” held back by an eel-skin ribbon. (Adams, Josiah. An address delivered at Acton, July 21, 1835: being the first centennial anniversary of the organization of the town, Boston: Printed by J. T. Buckingham, 1835, page 6)

It cannot have been comfortable to be a curiosity to young Actonians and to deal with attitudes made obvious by the meeting house seating vote. Nevertheless, some residents of African descent stayed in Acton. John Oliver farmed and raised his family with his wife Abigail Richardson. (Their known children were Abijah, Joel, Fatima and Abigail. We suspect, but have not yet been able to confirm, that there were others.) Cesar Tomson/Thompson was mentioned in town records when, on January 27, 1785, he married Azubah Hendrick (both were of Acton), Azubah was admitted to the church, and their children were baptized (Joseph, Moses and Dorcas). There is no record of what happened to Azubah, but Caesar married Peggy Green in Acton on December 1, 1785. He also appeared in town records on Feb. 23, 1789 when his tax rate was abated. While researching the Thompson family, we discovered that other Massachusetts towns’ vital records might hold clues about Acton’s Black residents. In Natick, we found two birth records (on the page before the 1801 intention of marriage for Dorcas Tomson, then living in that town): “Moses Hendrick son of Benjamin and Zibiah Hendrick was Born in Acton September 15. 1780 Dorcas Tomson Daughter of Ceasar and Zibiah Tomson was born in Acton April 1. 1784” In Grafton, we found a marriage intention between Polly Johns and “Moses Hendrick, ‘a native he says of Acton but now resident of Grafton,’ int[ention] Aug. 30, 1817. Colored.” Until we found these two records, we had no idea that a Black man named Moses Hendrick had been born in town. Another discovery was that at town meeting in August 1786, the town discussed suing Peter Oliver and Philip Boston “for Refusing to maintain Lucy W___ [name extremely uncertain, some think Willard] Child agreeable to their obligation.” Though both names were associated with free people of color in nearby towns, we have not figured out exactly who these men were or what their connection was to Lucy Willard. On March 19, 1792, the town paid Simon Tuttle Jr. for assistance given to Peter Oliver. The first full census of the United States came in 1790. Though only the heads of household were named, it gives us a more complete picture of the composition of the households in Acton. The census asked for the numbers of free white males (16 or older and under 16), free white females, slaves, and “all other free persons.” Acton had no slaves in this or later censuses. The census taker seems to have had some issues with accounting for “other free persons,” and the census scan is in places hard to read, but from what we can see, the following households had free persons of color:

The census shows six total free persons of color out of the 853 people in 1790 Acton. The seven people in John Oliver’s household were classified as white (2 males, 5 females), as were the nine members of William Cutting Jr.’s household (3 males, 6 females). In the beginning of the 1790s, Acton worked to specify those who were not considered legal residents, a step toward defining its responsibility toward the poor. The Revolutionary War had caused economic distress for many people in the new country. There were no safety nets as we understand them today. Then as now, towns were reluctant to tax people for any expenses that could be avoided. Under the system that had been in place since the early days of the colony, towns could avoid responsibility for supporting poor people if they were not considered legal residents of the town. Formally, this meant giving people notice that they had not been granted permission to live in town and that they should leave (and therefore that they had no right to expect help from the town if they stayed). This process was called “warning out.” From about 1767 to 1789, warning out seemed to be dying out in Massachusetts. However, a law change in 1789 led to a flurry of warnings out in Acton and elsewhere. In the 1790-1791 period, town records show that 23 households were warned out of Acton. Included were a number of Revolutionary War veterans and long-time inhabitants. John Oliver and Cesar Thomson, their wives, and their children were on the list. Both families stayed in town, as most warned-out people probably did in the 1790s. As a practical matter, if those people become indigent, assistance would still have been given them, but the town, relieved of its legal responsibility, could petition the state for reimbursement. Available in Harvard’s Anitslavery Petitions Massachusetts Dataverse is a July 1, 1796 petition from Jonas Brooks to the Commonwealth to reimburse the inhabitants of Acton for “considerable expense in supporting Caesar Thompson a negro man, together with his wife, three small children” who were “not legally settled in said Town of Acton or in any other town in said Commonwealth that your petitioner can find - That he served as a soldier in the Continental army during the last war...” The town sent a follow-up petition for state reimbursement in 1797. As a former slave, Cesar apparently had no legal claim on Natick (despite filling its quota in the Revolutionary War) or Boston, where he might have lived before serving in the military. After the petitions, we found no more records for Caesar Thompson; whether he died in Acton or moved, we were not able to determine. We do know that his daughter had moved to Natick by 1801. The 1800 census asked for more information than its predecessor. Only the heads of Acton households were listed, but the ages of white inhabitants were broken out more carefully. Acton’s census return had a column for the number of slaves and one for “All other persons except Indians not taxed.” With entries in that somewhat perplexingly-named column were the households of:

William Cutting Jr.’s household of seven was again listed as white. Also of note in the 1800 census is that many of the warned-out families were still in town. Acton’s vital records show that in December 1802, Sally Oliver married Jacob Freeman. Their relationship to people of the same surnames in town is unclear (so far). Sadly, Sally and Jacob had only a short marriage marked by tragedy. Their son died on Sept. 3, 1803. Jacob died on July 9, 1804 at age 45. Acton’s death record specifies his race as negro. (In early 1805, Amos Noyes, Joseph Brabrook, and Edward Weatherbee were paid for goods delivered to Jacob, presumably during his sickness.) 1810’s Acton census had a column for “All free other persons, except Indians, not taxed.” Acton households with someone in that category were:

John Oliver’s sons’ 1810 households were classified as white. The household of Abijah Oliver had 1 male 45+, 3 females <10 and 1 female 16-25. Joel Oliver’s household had 1 male <10, 1 male 26-44, 2 females 10-15, and 1 female 26-44. William Cutting Jr. was also classified as white. During the 1810s, town records show payments for some Black residents in need. Between 1813 and 1815, John Oliver was providing help to others, including Abijah Oliver and, when sick, “Abigal” Oliver and Sally (Oliver) Freeman. In 1811-15, John Robbins and David Barnard were reimbursed for boarding “Titus Anthony.” Later records give clues that he may have been Black (see below). (Probably relatedly, in March 1810, town meeting records mention a lawsuit by the town of Townsend against Acton “for supporting Hittey Anthony and Child.”) Acton town meeting took up Titus Anthony’s case in September 1811; unfortunately, the discussion was not reported in the extant records. In 1813, David Barnard was paid for providing for the poor and, separately, for “2 payment for the Negro” (name unspecified). 1820’s census yields more information about Black town residents. In that year’s report, “Free colored Persons” had four columns each for males and females of differing ages. Households with entries in those columns were:

1820’s total “free colored” population was listed as 17, which does not match the numbers given in the columns, so the accounting is uncertain. John Oliver’s 2-person household was listed as white. Regardless of the counting issues, there was obviously quite a community of people of color in Acton during the 1820s. Most lived in the North and East parts of town. The households of Jonathan Davis and Uriah Foster would have been near today’s Route 27 in North Acton. John Oliver’s sons Abijah and Joel eventually moved closer to East Acton; land records indicate that their father helped with financing. In 1830, federal census takers were given forms two page-widths across that specified ages and sex of both slaves and free people of color and had a “total” column for each family that should have encouraged accurate record-taking. The only household in which free persons of color were enumerated was John Oliver’s:

John’s son Joel Oliver was listed as white, living with 5 white females. Simon Hosmer’s family no longer was listed with a free person of color. This jibes with the hypothesis that the “Quartus Hosmer” mentioned by Josiah Adams lived in the Jonathan/Simon Hosmer household. In Acton’s vital records, the handwritten register of Acton deaths for 1827 shows: “June 30 Quartus a Blackman 61” The Hosmer name was not given in the death record. (This entry was indexed on Ancestry.com as “Quartus Blackman,” but that is clearly an error.) In Acton’s transcribed and published Vital Records to 1850, the listing appeared under “Negroes, Etc.” That entry adds information from church records (“C. R. I.”): “Quartus, ‘a Black man,’ June 30, 1827, a. 61 [State pauper, a. 64, C. R. I.] A state pauper meant that the individual had no “settlement” status. (Acton could not send him or her back to another Massachusetts town for financial support, but he/she was not officially accepted as having a claim on Acton either.) By this time, if a person with no official claim on a town was in need based on age, disability, illness or poverty, he/she became, officially, a state pauper, and expenses incurred by the town would be billed to the state. Apparently, former slaves often found themselves in this position (Cesar Thompson, for example), as well as new immigrants from overseas and anyone not connected to a town by family or marriage. Quartus’ status as a state pauper means either that he was free but didn’t start off in Acton or that he had started out a slave. If we are correct that the free person of color in the Hosmer household was this Quartus, he clearly had a long relationship with the family. The available records do not give us much information about what the relationship was, but we have not found evidence that he had been enslaved by Acton Hosmers. This Quartus was too young to have been the over-16-year-old slave in the 1754 census, though slaves younger than sixteen were not reported. The 1771 tax valuation showed no Acton Hosmers with “servants for life.” He could have been freed by then or could have been enslaved elsewhere in his early years and later entered the Hosmer household as a free working person. The 1840 census showed “free colored persons” in the households of:

The census shows the household of John Oliver, especially noted for being 92 years of age and a military pensioner, as white (1 male under 5, 1 male 5-9, 1 male 90-99, 1 female 5-9, 1 female 40-49). His son Joel Oliver’s household is also listed as white, (2 males, 30-39 and 60-69, and 2 females, 15-19 and 50-59). During the 1840s, many in Acton were advocating for an end to slavery in general and for improvements in laws affecting the lives of Massachusetts’ Black residents. A digitized 1842 petition from Acton to allow white people legally to intermarry with other races was signed by 70 women, including Abigail Chaffin who was most likely Abigail Richardson (Oliver) Chaffin, herself of mixed-race ancestry. (Abijah Oliver’s daughter, she had married Nathan Chaffin, born in Acton to Nathan and Mary Chaffin. After that point, records always seem to have classified her as white.) Abigail Chaffin also signed two other anti-slavery petitions in 1842 ( Petition against admission of Florida as Slave State and Petition to abolish slavery in Washington, DC and territories and to end the slave trade). Abigail Chaffin was remembered in a Chaffin family history (pages 269-270) as “one of the most remarkable women ever born in Acton, on account of the wonderful sagacity, industry and executive ability, which characterized her through the whole of her life and... together with mental and physical vigor, to a very rare age. ... Even after she was four score and ten she was able to do more for others than she needed to have done for herself.” After the death of her husband in 1878, she moved in with her son Nathan who prospered in the restaurant business in Boston. She lived in Arlington for many years, and she died in Bedford in 1911, after having “passed her last years not only in the possession of the comforts, but of the luxuries of life.” Back in Acton, the 1850 census, for the first time, listed the names of all residents of the town. A column for race showed the following residents of color:

The race column for all other residents was left blank (including the 7-person household of Joel Oliver, Abijah’s brother). The 1850 real estate valuation for the town shows Ephraim Oliver (son of Joel) with buildings valued $375, plus 40 acres of improved land and 20 acres of unimproved land; he was living with Joel at the time. Abijah Oliver had been farming in East Acton, but obviously he was no longer able to care for himself. It was not particularly unusual for the aged, regardless of race, to need assistance. Massachusetts took its own census in 1855. We have noticed in the past that the Acton census taker that year was particularly careful in recording full names, and the census taker noted more information about race as well:

We have not yet been able to find out where Titus Anthony Williams came from and how he ended up in Acton’s poor house. The middle name reported in the 1855 census raises the question of whether the “Titus Anthony” who was receiving assistance in the 1810s was actually the same Titus Anthony Williams who spent many years in Acton’s poor house (occupation farmer). If so, he would have been a young child when he first appeared in Acton’s records. By the mid-1800s, Acton was changing. The arrival of the railroad brought new industry and new people to town, and events in Europe brought new immigrants who would have competed for jobs and land. Most descendants of Acton’s early Black residents eventually left Acton to find opportunities elsewhere. Occasionally, they were mentioned in later records. Sickness, disability, loss of a breadwinner, or extreme old age could change economic status. Acton’s town report of 1855-1856 shows payment to the city of Boston for the support of Elizabeth Oliver (probably the recent widow of Abijah Oliver), and to the town of Concord for the burial of two of Peter Robbin’s family, as well as to Daniel Wetherbee of Acton for goods provided to that family. (Peter Robbins had recently died. He was divorced from John Oliver’s daughter Fatima by that time; apparently, his common law wife Almira/Elmira came from Acton, though her parentage is currently unclear. She is referred to in Acton’s records as Elmira Oliver.) The 1857-58 report shows money paid to Lowell for the support of Sarah Jane (Tucker) Oliver. (She apparently married William P. Oliver and then Asa Oliver; their connections to other Acton Olivers are still being worked out). Others receiving help that year who were not living at the poor farm included Sarah Spaulding (John Oliver’s widowed granddaughter) and Elizabeth Oliver. The 1860 Federal Census showed the following: