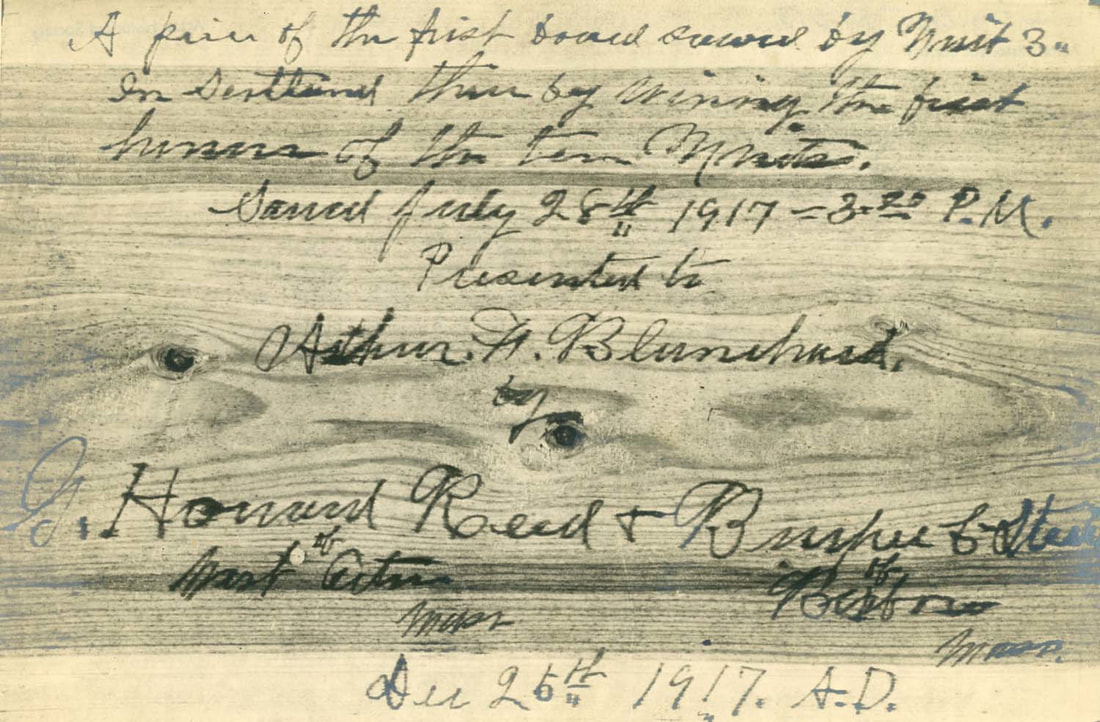

One of the almost-forgotten aspects of warfare in World War I was the dependence of the military on wood supplies. The Allies’ war effort required a tremendous amount of lumber for their operations. It was used for shoring up trenches and mines, lining roads to make them passable after destruction by shelling and overuse, building structures such as hospitals, ordnance depots and bridges, supporting barbed wire barriers, and manufacturing smaller but necessary items such as boxes for shells. There were still forests in Britain, many on private lands, but the manpower needs of the war had created a shortage of labor to cut them down. In April 1917, a colonel attached to the British War Office sent a cable to an American colonel in Boston mentioning this critical need. Lumbering was something at which Americans had experience to offer. Government and industry leaders in New England decided to recruit and equip ten units of skilled men and send them to the Allies’ aid. Getting approval from both sides of the Atlantic took a month, so the practical work started in mid-May. Part of the committee that got the process going was Arthur F. Blanchard of West Acton. Each New England state pledged to equip a sawmill unit at an estimated cost of $12,000-$14,000 each, including the cost of food, lodging, medical care, and the issue of “hat, shoes, mackinaw and oilskins” (Boston Daily Globe, May 23, 1917, page 10). Private lumbering companies, including Blanchard’s, pledged money to pay for four additional companies. The British government would provide transportation to and from England and would pay the men’s salaries from the time of sailing, for a term of up to a year’s service. According to the Boston Daily Globe (June 12, 1917, page 4), some people predicted that the venture would fail because of scarce labor in lumbering in the United States. This concern was unfounded. The committee advertised and within two days had enough men for three units. Many applications were reviewed and eventually whittled down to about 35 men per unit plus support staff. One of the units was composed mostly of men from Acton and surrounding towns under the leadership of Arthur Blanchard’s son Webster. Locally, it was thought of as the Blanchard & Gould company, but its title was New England Sawmill Unit No. 3. The logistics were daunting. Each unit was to have a portable sawmill and everything it needed to function independently for a year, including an engine and boiler, wagons, axes, saws, blacksmiths’ and carpenters’ tools, harnesses, lamps, cooking utensils, bedding, and other camp equipment. Over two thousand different items were procured, carefully accounted for so that each would go to the proper unit, and delivered to Boston. One-hundred and twenty work-ready horses were bought and kept in Watertown until it was time to ship out. On the personnel side, men had to be found who were experienced, “of good character,” and willing to sail on two days’ notice. Each man needed to be approved for a passport and to sign an individual contract with the British government. Not only were men needed to deal with cutting, transporting and milling the lumber, (in roles such as the interestingly named “head chopper” and “swamper”), but there was also need of cooks, bookkeepers, blacksmiths and veterinary support. In an amazing feat of cooperation and organization, the ten units were created, equipped, and ready to go in a month. America’s military was just gearing up at the time, and New Englanders were proud of getting help to their allies so quickly. A self-congratulatory note appeared in an industry publication: “There was not an amateur or an epaulette connected with the affair. It was worked out practically – hence its success.” (Lumber World Review, Nov. 10, 1917, p. 54) When organized, the lumbermen convened in Boston where they stayed at the South Armory. The committee had organized a welcome for them, arranging for them to see a baseball game and be eligible for free motion picture and vaudeville performances. At least some of the men also participated in the Elks’ Flag Day parade, accompanied by their mascot, a black bear cub. The Saw Mill Unit’s send-off seems surprisingly generous, but they were in the vanguard. There may also have been a less generous motivation; the organizers seem to have been nervous about lumberjacks running amok. “The Ten Mill Units are a civilian, not a military organization, so it was impossible to impose military discipline on the men, many of them loose in a large city for the first time in their lives. However, it must be said, that the men behaved a lot better than anticipated.” (Lumber World Review, November 10, 1917 p. 54) On the evening of June 14, they were feted at a banquet at the Boston City Club. The Christian Science Monitor noted the next day the unusual nature of the dinner as members of the club and the Public Safety Committee in dress suits mingled with lumberjacks, “some in overalls, moccasins, flannel shirts and bared arms, the type of men who fought in the American Revolution.” (June 15, 1917, p 7) Despite concerns over attire, it was reported to have been a successful event. For the organizers, there was some stress as departure-time approached, because some of the expected men did not show up. According to the Lumber World Review article, as late as the morning of the day of departure, they were missing three cooks and a couple of blacksmiths. Somehow they were able to fill the slots, “although the last cook got over the gang plank just as it was being raised.” (p. 54) The Sawmill Unit sailed to New York, arriving on June 16th. On the 18th, they sailed on the troopship Justicia to Halifax, staying in port until June 25th, when they were joined by 4,000-5,000 Canadian troops and headed across the Atlantic. A letter written at sea by Whitney Bent described the trip. (Concord Enterprise, July 25, 1917, p. 7) Two ships accompanied them at a distance of about ¾ of a mile, one with the horses and wheat and one that carried nitroglycerine. The Justicia apparently also carried wheat and lumber. The letter did not mention where all the equipment was, perhaps with the horses. It was, fortunately, a relatively smooth sail. The men were required to wear life preservers at all times. They slept in tightly-arranged hammocks, alternating in direction of head and feet. For most of the journey, there was not much to see except the other ships and occasional whales, although the men kept busy with “church, boxing, cards and reading” and received news and baseball scores by wireless. A dog fight between different groups’ pets interrupted the monotony. On July 3, Bent added to his letter that they had been joined by “submarine chasers” and there were possible submarine sightings that day and the night before. The Boston Daily Globe, (Aug. 19, 1917, p. 36), printed a letter from Hugh Connors of Maynard who also described the trip. “We arrived, as you probably know, July 5, [in Scotland], after a long tiresome trip. The last two days we were in the war zone. We had been on the boat so long that some of the boys didn’t care whether we were torpedoed or not.” According to Mr. Connors, at the end of the trip, the boat was fired upon by two German submarines. Two torpedoes were fired, but missed by 12 feet or less. A contrasting letter, written to the head of the organizing committee back in Massachusetts by Downing P. Brown, general manager of the ten mill units, said that “For a time there was considerable conjecture about the possibility of submarines, etc., but as soon as the fleet of destroyers arrived, the tension relaxed and everyone felt safe.” (Lumber World Review, Nov. 10, 1917, p. 56) The different tone may have been because of censors. The Boston Sunday Globe (Aug. 26, 1917, a.m. edition, p. 10) quoted a letter from Hap Reed to his parents that the Atlantic crossing was “a most bitter experience – more than I can write about” and that British censors were keeping the men from revealing details of the trip. Whatever actually happened, it was a dangerous time to cross the Atlantic. After landing in Liverpool, the “lumberjack unit” took a train to northern Scotland where they were to work in forests on private estates, including that of Andrew Carnegie. Unit No. 3 worked at Ardgay. They had to wait for their equipment to arrive by boat. The Concord Enterprise (Aug. 22, 1917, p. 3) reported that the “Blanchard & Gould mill known officially as Unit No. 3. had the distinction of cutting and sawing the first lumber on foreign soil for the cause of the Allies, by an organized body of men and complete equipment from the United States.” The first work was done by Burpee Steele of Boxboro and G. Howard Reed of Acton. Three officers from the general staff were present and inscribed a piece of wood with “First Lumber Sawed by American Lumbermen in this Country, July 28, 1917 at 3:20 p m.” A portion was inscribed by Reed and Steele and given as a gift to Arthur Blanchard for Christmas, 1917. The Society has a picture of the inscription. Once the mills were up and running, the men worked hard. Friendly rivalry seems to have boosted their productivity; letters home periodically mentioned units’ records relative to the others. An unsourced newspaper clipping in the Society’s collection (from sometime after March 23, 1918) reported that Unit No. 3 was proud to have been the first to reach the million-foot mark. They were also pleased that they increased their productivity enough in December, 1917 to maintain their weekly average output despite Scotland’s low sunlight at that time of year and a week off at the end of the month. The men of the whole Sawmill Unit were treated well by the local inhabitants of the region and seem to have caused little trouble, though a retrospective article in the Northern Times mentioned occasional rowdiness, attributed to the locals being a bit too generous in supplying alcohol. (It also mentioned one serious accident that we did not find in our local newspapers.) Published reports of the time generally focused on lumber production, not leisure activities, but we do know Unit 3’s clerk Glenn Gould was considered the unit’s musician and seems somehow to have had access to a phonograph. We also know that about half of the sawmill men took the train to London for their December break to see the sights. There must have been some time for mingling, because according to the Boston Sunday Herald, “more than a dozen Scotch wives” would head to America when the Sawmill Unit returned (June 30, 1918, p. B2) By all reports, the Sawmill Unit was a success. The men produced more than 20,000,000 feet of lumber for the Allies. Though they were exempt from the draft during the term of their contract with the British government, they worked long hours and completed the job early. According to a Boston Globe article, the New England Sawmill Unit was commended by the British government for doing “twice the work at half the cost of any organization producing lumber for war service.” (Dec. 1, 1918, p. 16) Their efforts were also noticed by soldiers in the trenches. The same article quoted a soldier’s letter that having boards lining the trenches “was particularly appreciated in wet weather, when we were protected from the mud and water which otherwise would have been around on all sides.”

Though the Sawmill Unit fulfilled their contract, the war continued. Most of the men of the unit, as soon as their work was completed, enlisted in the military. Apparently, their status had been subject to much “diplomatic correspondence” between the British and American authorities. “Many of the young men resented the fact that they were published in their districts as delinquents [from registering for the draft], though their records were ultimately cleared.” (Boston Globe, June 16, 1918, page 7) Over a hundred of them joined the U.S. Army’s 20th Engineers who dealt with overseas forestry activities. Six Acton men from Sawmill Unit No. 3 were among them. A large number of the sawmill men, including Webster Blanchard, went into the Navy. That sounds surprising, but there were significant naval operations near northern Scotland. We did not find any mention in newspapers on this side of the Atlantic of what happened to the animals and equipment after the sawmill unit disbanded. However, we did find a June, 1919 ad in the Aberdeen Press and Journal stating that the Timber Supply Department of Scotland was selling ten portable New England Sawmills, complete with spare parts. That September, the first reunion of the New England Saw Mill Unit was held in Boston. Twelve local men attended, and “Webb” Blanchard presided. The Society is lucky to have a collection of Webster Blanchard’s photographs showing Unit 3’s and other sawmills in operation, the Unit 3 crew, the horses, and even the pets that they brought over with them. You can view the photographs at Jenks Library during our open hours or in our online World War 1 Exhibit. We would like to add to our collection; if anyone has photographs with members of Unit No. 3 identified, letters written by them from Scotland, or any other Acton-related World War 1 pictures and materials, we would be grateful for donations, copies, or scans. Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed