|

4/8/2024 The Page that was MissedResearch for our latest blog post involved searching the 1855 Massachusetts census for all Acton residents who were born in Ireland. Using one of the available online indices, a list could be generated quickly, and then linked images of the census forms allowed us to check each individual’s details and make sure that we had not missed anyone in town born in Ireland. Aside from some creative name-spelling and questions about ages, we thought we had a complete list of Acton’s 1855 Irish-born population. We should have known that the process was too simple.

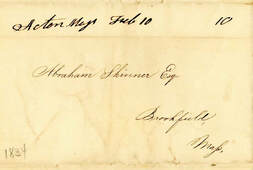

A few years ago, the Society received a donation of a book containing a handwritten “Census of Acton taken June 1st 1855 by Samuel Hosmer, Agent for Selectmen & Assessors.” This 1855 census listing was entirely handwritten, not a set of filled-in census forms. Because we have easy online access to census images through genealogical websites, it had never seemed important to study our census book in detail. While working on the Irish data, however, we took a look at what was actually in the book. To our surprise, on the first page, in the first household, there was a young Irish woman who was not included in our list of Irish-born residents. Thinking that it was perhaps an indexing problem with the spelling of an Irish name, we tried searching the online 1855 census database for the Massachusetts-born individuals in the same household. They were also missing. Moving down the handwritten page, we found that none of the people listed by Samuel Hosmer in the first 6 Acton households, plus part of the seventh, was included in the online index. Three commonly-used online databases gave us the same result; none of them included people from the first 6+ households in our handwritten 1855 census book. The first person who appeared both on our book’s first page and in Ancestry’s 1855 census database was Emma Francis [sic] Estabrooks, age 1 year, 11 months. The online image of the census form showed that Emma was listed on the first line of a filled-in, preprinted Acton census form. There should have been a previous form that listed her parents, but when we tried to access the previous page, we found that there was no image other than the cover of a bound volume Census of Massachusetts 1855, Vol. 19, Middlesex Co., Acton to Cambridge. We had the same result using FamilySearch and another online database; presumably, they all used the same source. (Though stated sources and dates vary somewhat across the different databases, they seem to have come originally from microform/microfilm of the census held at the Massachusetts State Archives.) It appears either that the original filming missed the form that contained the first 6.5 households in Acton’s enumeration or that the first form was actually lost. Either way, the indices and digital images of Acton’s 1855 census that are being used regularly for research are missing 36 Acton residents. We offer here the missing page 1 of Acton’s 1855 census for everyone who is searching for the following 36 individuals. Some were life-long Acton residents, but others only seem to appear in Acton’s census records here. All listed individuals were born in Massachusetts, except as noted. Seven of the missed individuals were born in Ireland. (We included them in our blog post on Irish in 1850s Acton.) Samuel Hosmer’s 1855 Census of Acton: Dwelling & Household 1

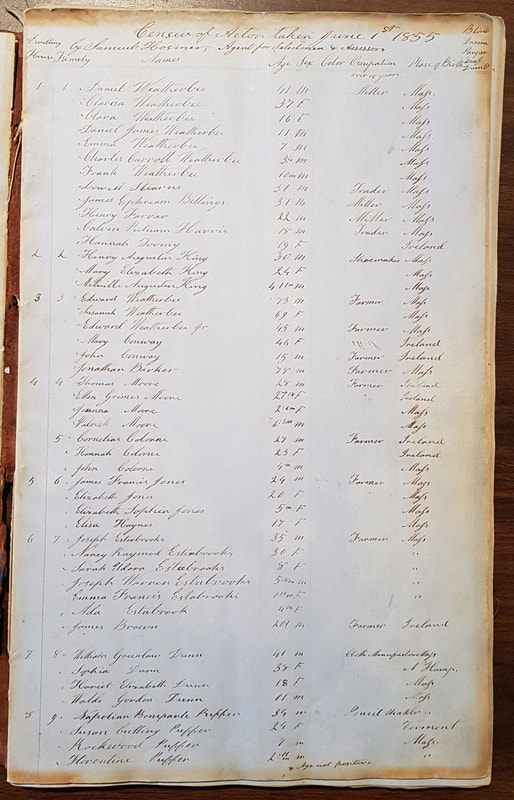

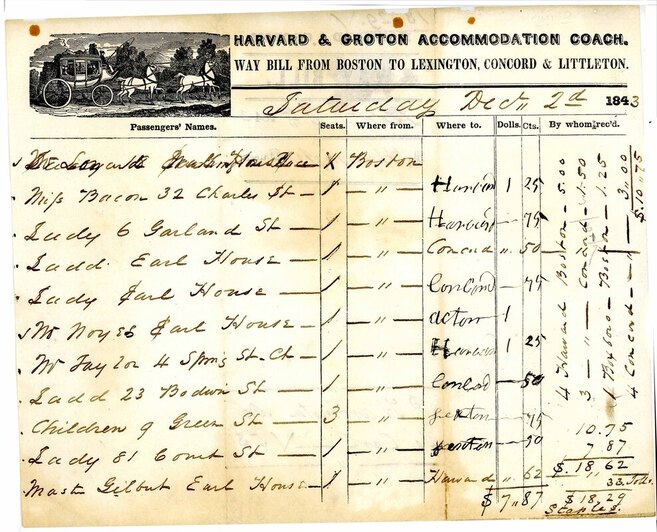

Note that the name Weatherbee was more often spelled Wetherbee in Acton. The name Esterbrook(s)/Estabrook(s) is differently spelled even within the same family here and appears in different forms in various Acton records. Further research did not help us to confirm the Irish name Colorne and what other forms it might have taken. Records for other individuals in the 1850s yielded other possible names such as Coborne and Coline. 4/24/2023 Stagecoaches Through ActonOur document collection contains a way bill listing passengers who rode a stagecoach from Boston on Saturday, Dec. 2, 1843. Among the passengers was Mr. Noyes who caught the coach at “Earl House” and headed to Acton. The document is a souvenir of travel just before Acton’s transportation choices changed dramatically. Prior to the arrival of the Fitchburg Railroad in 1844, as Fletcher’s Acton in History tells us, travel to and from Boston “was slow and difficult. The country trader’s merchandise had to be hauled by means of ox or horse-teams from the city. Lines of stage-coaches indeed radiated in all directions from the city for the conveyance of passengers, but so much time was consumed in going and returning by this conveyance that a stop over night was absolutely necessary if any business was to be done. ... a visit to Boston before the era of the railroad was something to be planned as a matter of serious concern. All the internal commerce between city and country necessitated stage-coaches and teams of every description, and on all the main lines of road might be seen long lines of four and eight-horse teams conveying merchandise to and from the city. As a matter of necessity, taverns and hostelries were numerous and generally well patronized.” (p. 268) Coaches required fresh teams of horses at intervals, so stops were usually made every 8-12 miles. Acton had taverns before the stage routes (for example Mark White’s at 274 Great Road and Jones Tavern in South Acton), but as stage travel became more prevalent, taverns and inns multiplied as well. Shattuck’s History of Concord says that the first public stagecoaches came from Boston “into the country through Concord, in 1791, by Messrs. John Vose & Co.” (p. 205) Ads for stages between Boston “and the country north-west thereof” were being advertised in the Columbian Centinel in 1793, leaving from Charlestown and passing through Concord and Groton. Acton was not mentioned specifically, but presumably stages traveled via today’s Great Road, coming from Concord, through East Acton, by Nagog Pond, and on into Littleton. That route was noted as “Littleton Road” on a map drawn by Jabez Brown in 1794 and was also in early days referred to as the Groton Road. Like later decisions about railroad routes, decisions made elsewhere about stage and mail routes would have significant effects on businesses in outlying towns. The Columbian Centinel ran a series of proposals in 1794 that indicated that the mail route from Boston to Keene and other points in New Hampshire had not yet been settled. It would either go through Concord and Lancaster or Concord and Groton. Later, there seem to have been disputes among “interested persons” such as innkeepers about whether there was a significant difference in distance between the Groton-to-Lexington routes via Carlisle or Concord. (Green’s Historical Sketch, p. 193) By June 1810, the Boston Patriot was running ads for competing stage lines that explicitly mentioned Acton. Luther Carlton advertised the Concord, Harvard & Winchendon Stage that left Boston on Wednesdays & Saturdays at 7 a.m., passing through West Cambridge, Lexington, Concord, Acton, Boxborough, Harvard, Shirley, Lunenburg, and Fitchburg. (On Saturdays, it continued on to Ashburnham and Winchendon.) Return trips were on Mondays and Fridays. (June 23, p. 4) Meanwhile, a “new Arrangement of the old Concord and Leominster MAIL STAGE” was leaving Boston on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays at 5 a.m. going through Cambridge, West Cambridge, Lexington, North Lincoln, Concord, South Acton, Stow, Bolton, Lancaster, Leominster, South Fitchburg, Westminster, Gardner, Templeton, Gerry and Athol. The return stage left Athol at 4 a.m. on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, arriving in Boston in the evening. The latter ad noted that the meal stop was at the Hotel in Concord. (June 2, p. 4) On March 16, 1827, the Boston Traveler advertised that the Boston and Keene Union Stage Company ran a daily stage line leaving Boston at 5 a. m., passing through Lexington, Concord, Acton, Groton, Townsend, Ashby, Rindge (NH), Fitzwilliam (NH), Troy (NH), and Keene (NH), arriving at 5 p.m. in Charlestown (NH). Connections from Keene and Charlestown allowed travelers to continue on to points in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Saratoga Springs. “The Company have been to great expense in purchasing the best of horses and carriages and employing the most careful and obliging drivers, and have spared no pains in establishing the line that it shall not be exceeded by any other from Boston for dispatch and convenience of passengers. They have fourteen changes of teams between Boston and Charlestown, giving only about eight miles for each set of horses.” (p. 3) Stage coach stops such as those advertised by the Union Stage Company encouraged the growth of taverns and inns. Fletcher tells us that “in the east part of Acton, on the road leading from Boston to Keene, there were no less than four or five houses of public entertainment.” (p. 268) An 1831 map shows “Weatherbee’s” (65 Great Road), “Hatgood’s” (really Hapgood’s at 162 Great Road) and White’s (514 Great Road) taverns along Groton Road. The earlier White’s Tavern had been opened in 1755 and operated for a number of years, but it was not in operation in 1831. Fletcher’s History also notes that additional demand for taverns was from drovers who would accompany livestock to their summering pastures in New Hampshire. Wetherbee’s Tavern was well-known to drovers and drivers of baggage-wagons all the way to Canada. (Fletcher, p. 294)  Hosmer Tavern, 471 Mass. Ave., c. 1930s-1940s Hosmer Tavern, 471 Mass. Ave., c. 1930s-1940s Another stage route through Acton followed the Union Turnpike, although as originally surveyed, it had some steep grades farther west that were not popular with stage coach drivers. During the cash-strapped post-Revolutionary War years, the expansion of long-distance roads was often accomplished by for-profit ventures that would involve building a road and then collecting tolls, often at bridges. The Union Turnpike was approved by the Massachusetts Legislature in March 1804 and started operating in 1809. Joel Hosmer of Acton, seeing a business opportunity, enlarged his father’s house at 471 Massachusetts Avenue along the Union Turnpike route to serve as a tavern. (Joel Hosmer appears as one of the names attached to the Union Turnpike Corporation in the legislative act that established it.) The History of Harvard tells us that once Harvard got its own post office around 1811, the Harvard, Lunenburg and Winchendon stage would come with mail and passengers from Concord over the Union Turnpike. Those coaches would stop at a tavern in Harvard (the half-way point) for meals. Hosmer’s Tavern, like the Turnpike itself, was not a profitable venture. The Union Turnpike’s competitor route, the Lancaster and Bolton Turnpike, had easier grades. After the Union Turnpike’s bridge in Harvard was swept away by flooding in 1818, it was not rebuilt. The overly-steep grades were eventually abandoned and what was left of the turnpike in Middlesex County became a public road in 1830. Today, Acton’s Massachusetts Avenue (Route 111) follows the route of the old turnpike. During the 1830s, changes in transportation were happening elsewhere, but coaches kept running through Acton. The Daily Evening Transcript on Sept. 2, 1833 advertised the Lunenburg & Boston Mail Stage, leaving Boston on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays at 8 a. m., arriving in Lunenburg at 4 p.m., passing through Cambridge, Concord, Acton, Harvard, Still River Village, Shirley Village, and Shirley. One could buy tickets at Brigham’s, 42 Hanover Street, from proprietor William Shepherd. The Bay State Democrat ran an ad on June 3, 1840 for a new line of post coaches to Harvard, MA that would go from 9 Court Street, Boston, via Cambridge, West Cambridge, Lexington, Bedford, Concord, Acton and Boxboro on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. The Worcester Palladium advertised on March 31, 1841 proposed (presumably mail) routes, for two-horse coaches. The first was from Concord to Shirley by way of Acton, Boxboro and Harvard, 18 miles in four hours (Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, to leave at 2 p.m.). The return trip was to leave Shirley on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 7 a.m. The second route was from Worcester to Lowell, going through Boylston, Berlin, Feltonville, Stow, Acton and Chelmsford. We found no further information on the latter route. In terms of time and place, the ad most relevant to our way bill was found in the March 24, 1843 Boston Traveler. U.S. Mail Coaches would start out from Boston at 10 A. M., leaving from the office at 9 Court Street and 36 Hanover Street on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays for Lexington, Concord, Acton, Boxboro, Harvard, Shirley Village and Leominster Village. The return trip was from Harvard at 9 A. M. Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Our way bill was a Saturday run with 12 passengers (including some children). Mr. Noyes left for Acton from Earl House, listed in the 1842 Boston Almanac as Earl’s Coffee House, operating at 36 Hanover Street. The driver, P. Harrington, may have been Phineas Harrington who, according to Samuel A. Green’s Groton history, had a long career as a stage coach driver in the area. By the time Mr. Noyes took his trip to Acton in Dec. 1843, transportation patterns were changing. Railroads were already providing an alternative to stagecoaches elsewhere. The Fitchburg Railroad was completed to West Acton in the autumn of 1844, and Fletcher says, “that village became a distributing point for the delivery of goods destined for more remote points.” (p. 268) An ad from the Boston Courier on Oct. 28, 1844 tells us that “down trains” to Charlestown would leave West Acton at 7:36 and 10:51 am and around 5 p.m. Trains from Charlestown would leave at 8 a.m. and 1 and 4:30 p.m. After the 8 a.m. train arrived in Acton, stages would leave from there every day except Sunday for “Littleton, Groton, Townsend, Lunenburg, Fitchburg, Ashburnham, Winchendon, Westminster, South Gardner, Templeton, Phillipston, Athol, Mass.; Fitzwilliam, Troy, Swansey, Keene, Walpole, Charlestown, N. H.; Chester, Windsor, Woodstock, Rutland, Middlebury, Royalton, Montpelier, and Burlington, Vt.” There were other stages that only traveled three days per week for points in western Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, as well as Albany, NY. After the first train arrived in Acton just after 11 a.m., stages would leave for “Stow, Boxboro’, Bolton, Harvard, Lancaster, Leominster and Fitchburg” on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, and for Littleton and Groton on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. As the railroad was extended and lines proliferated, transportation patterns changed rapidly. Both South and West Acton kept growing thanks to the railroad, but Acton was only a stage hub for so many other destinations for a short time. Eventually, stagecoaches became a thing of the past. We are lucky to have in our archives a tangible reminder of those earlier days. Sources:

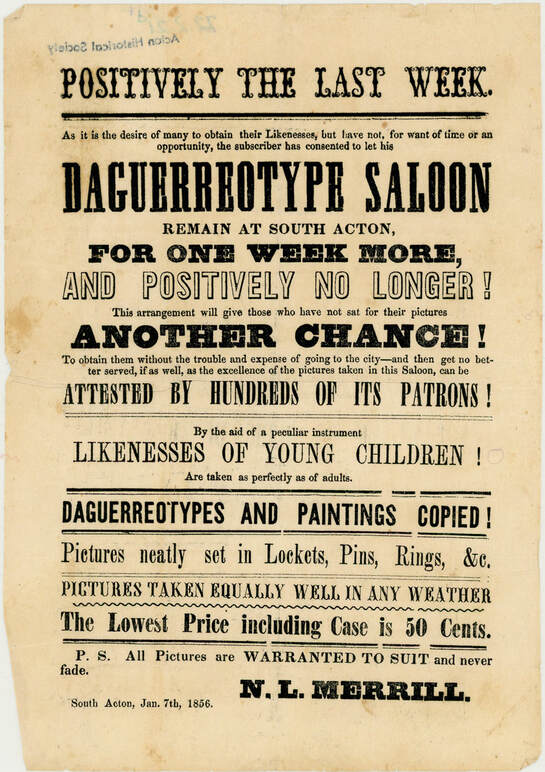

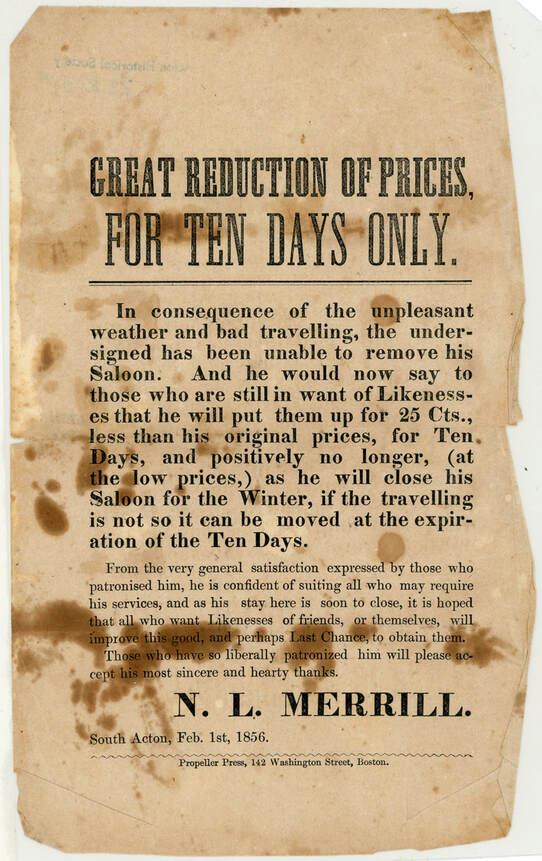

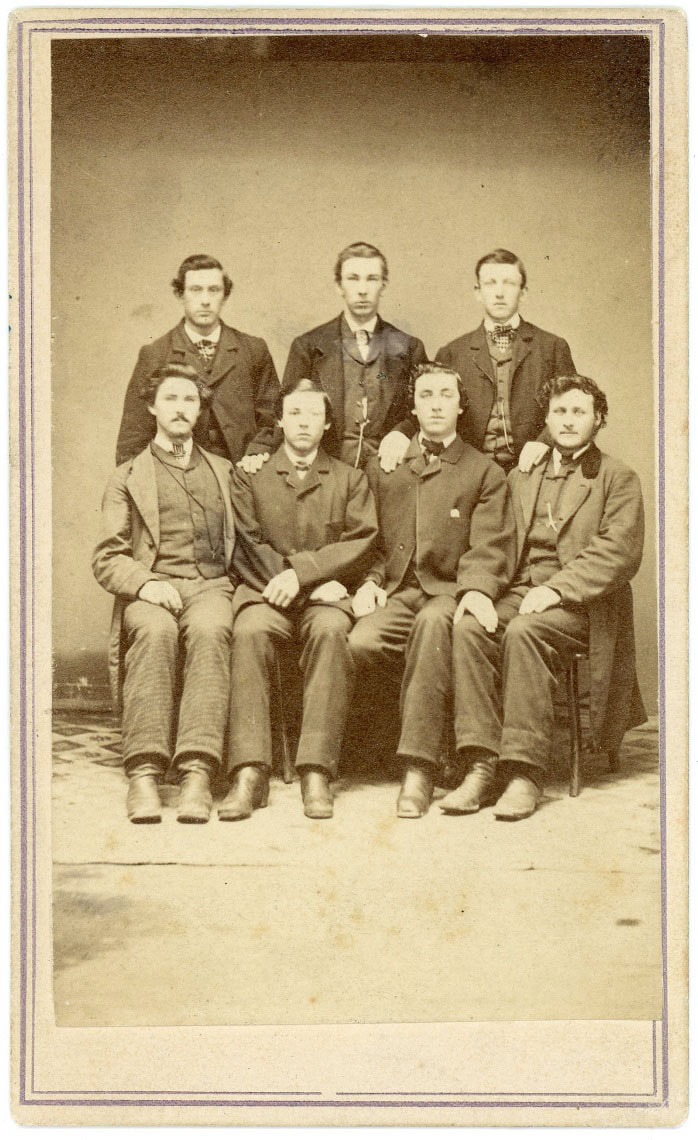

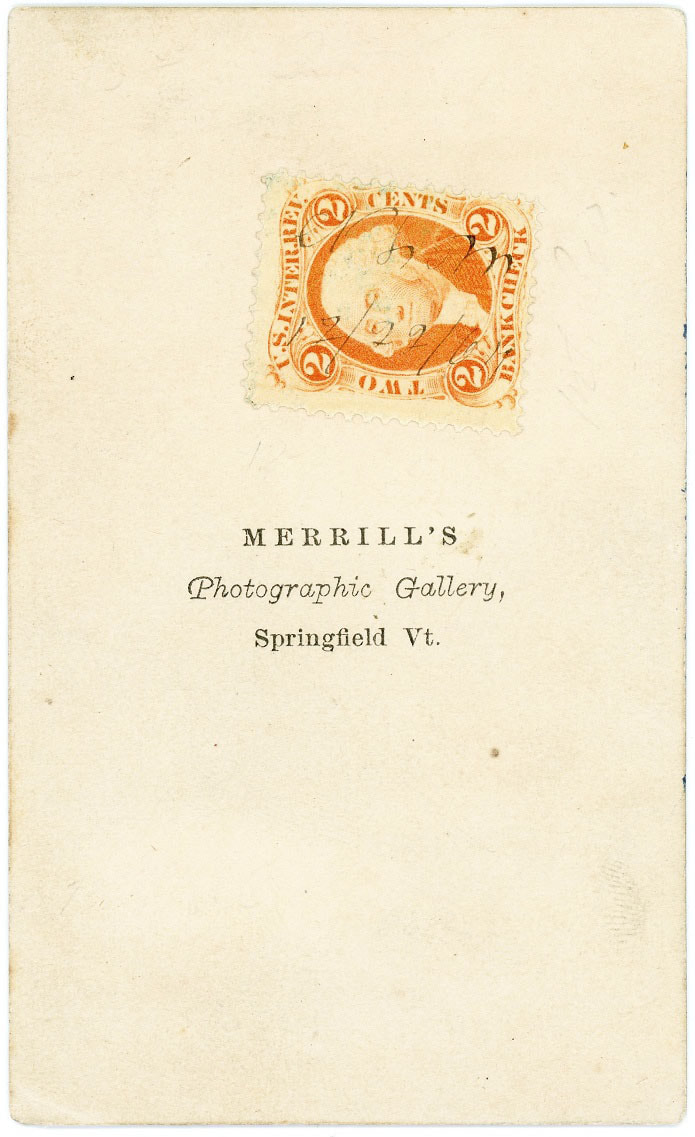

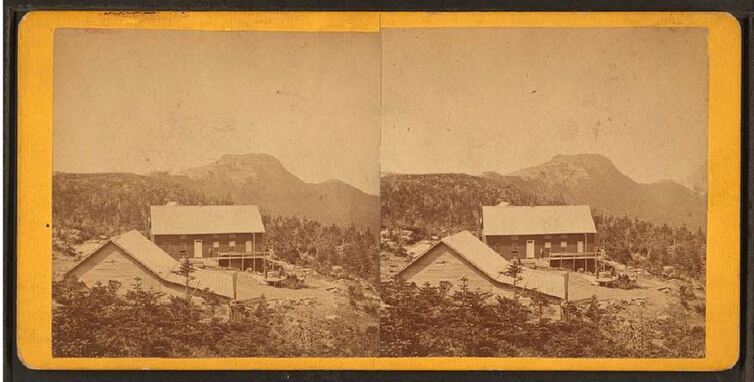

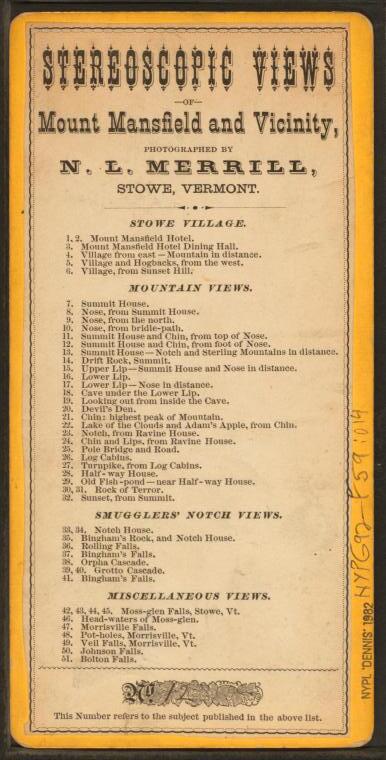

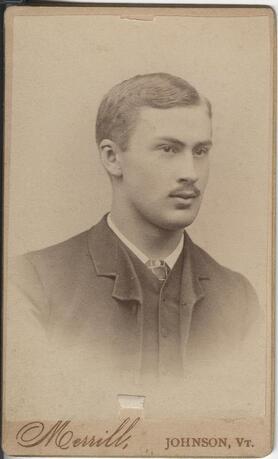

We are also grateful to the following websites for sharing information and sources on stage routes in other towns (all accessed April 23, 2023): 10/29/2022 A Real Diary or a School Project?In one of the scrapbooks at Jenks Library, there is a page of copied newsprint columns. The date, title, page number, and publication place of the newspaper are unknown, but the page includes, “Diary of Sarah Faulkner. Born March 18, 1756, of Colonel Francis Faulkner and Lizzie Muzzey Faulkner.” Quoted excerpts follow about events leading up to and during the American Revolution. At first glance, the page could seem to be describing a firsthand source about Acton, produced by a young woman at a critical time in its history. The account was originally indexed in our files merely as “Sarah Faulkner’s Diary,” but more investigation showed that our page came from a high school history composition completed in 1936. What struck us was how easy it would have been, if that “diary transcription” had been posted online, for someone’s imaginative exercise to spread as “fact.” Transcriptions that we find on the internet can be wonderful sources that allow us to search for topics of interest quickly and easily. Sometimes the original can be very hard to track down, but as our example shows, it is worth finding out where a transcription came from. It is especially helpful when transcriptions are accompanied by digitized versions of the original documents. For example, in Acton we are lucky to have online access to our earliest town records, both digital images and indexed and searchable transcriptions, thanks to the efforts of Acton Memorial Library and some dedicated volunteers. (Original, Transcription) Jenks Library and many other archives have extensive collections of diaries, journals, and letters, many of which have never been transcribed. While they can be frustratingly incomplete when one is looking for a specific piece of information, they are incomparable sources for understanding the actual interests and concerns of people in earlier times. A small sampling of original sources in our collection: A fascinating set of handbills in our collection advertised a photographer working in South Acton in early 1856. N. L. Merrill announced on Jan. 7th that for “positively the last week,” his Daguerreotype Saloon would be operating and could save locals from going to the city to “obtain their likeness.” Pictures could be taken regardless of the weather. Merrill could even take pictures of young children “by the aid of a peculiar instrument.” He also would copy one-of-a-kind daguerreotypes and paintings. A second flyer dated Feb. 1, 1856 stated that bad weather and travel conditions had kept his Saloon in South Acton. For an additional ten days, he would provide likenesses discounted by 25 cents, after which he would move on or close down for the winter. Who Was N. L. Merrill? Curious, we consulted Steele and Polito’s monumental work A Directory of Massachusetts Photographers 1839-1900. No N. L. Merrill was listed there. Further research yielded no one of that name operating as a photographer locally, so we had to search farther afield. The only likely candidate for the South Acton Saloon’s owner was a photographer who later operated mostly in Vermont, Nathaniel L. Merrill, usually known by his initials. Oddly, we were not able to determine exactly where he came from, how he came to be in South Acton, or where he went when the weather allowed him to move on. Though historians have written about daguerreotype studios in major cities, it is very hard to learn about pre-Civil War itinerant photographers. They would have been on the move constantly, and their advertising, by handbills passed around and probably posted somewhere in town, did not generally leave traces for researchers to follow. The fact that N. L. Merrill’s South Acton flyers were preserved long enough to end up in our archives is quite remarkable. Assuming we are correct about N. L. Merrill’s identity, we were able to learn about his later career. The search took us miles from Acton but revealed the challenges of an early photographer who repeatedly adapted to changing technology and kept moving to find new markets. Digitized records, newspapers, and photographs allowed us to discover at least some of N. L. Merrill’s travels; we suspect that there were more. The early life of N. L. Merrill was difficult to uncover. The earliest information we found was a newspaper mention that “he was an excellent artist when we knew him at Irasburgh (VT), in 1850.” (Orleans Independent Standard, April 10, 1868, p.2) It seems that he traveled with a portable studio, sometimes referred to as a “daguerreotype saloon car” or a “moveable saloon.” He would presumably stay until the customers dwindled and then move on. Apparently in the course of his travels, he met Prudentia D. Waters whom he married on Jan. 25, 1853 in Johnson, Vermont. Prudentia was born and raised in Johnson, and the couple may have considered that place their home base for at least some of their time together. Unfortunately, the marriage record gives us no information that would help either to pinpoint Nathaniel Merrill’s origins or to distinguish him from many others of the same name. The record said that he was living in Portland, Maine at the time, but a Portland directory for that year yielded no photographer N. L. Merrill. Further research in the area turned up nothing useful. The next evidence of him is the pair of 1856 handbills in our archives. The 1860 census recorded him in Nashua working as an "artist," though that is the only evidence we found of him in New Hampshire. After 1860, N. L. Merrill is much easier to find because he turned to newspaper advertising and produced paper photographs with his name and location on the mats. In March 1860, the Bellows Falls Times announced that N. L. Merrill was in town with a saloon where he was taking pictures “in a very superior manner.” The enterprising Mr. Merrill had furnished the newspaper with a copied photograph that elicited a great deal of enthusiasm from the reporter. Merrill ran ads at times in the Bellows Falls Times between the summer of 1860 and at least Feb. 1862. By now he had changed technologies and was apparently settling down for a while. He announced: "MERRILL’S PHOTOGRAPH & AMBROTYPE SALOON, SPRINGFIELD, VT. The public are invited to call and examine his specimens, the only place in this vicinity where COLORED PHOTOGRAPHS ARE TAKEN. By this process life-like pictures may be obtained from old and inferior Ambrotypes and Daguerreotypes, and warranted to give satisfaction. The negative is always preserved, and persons wishing duplicates can have them at any time by ordering. LOCATED IN THE SQUARE.” (among other ads, this ran in the Bellows Falls Times, July 20, 1860, p. 4) During the Civil War years, Nathaniel L. Merrill seems to have spent a good deal of his time in Springfield. He was there working as a “Photographist” when he registered for the draft and was taxed for a photographer’s license in the 1862-1865 period. Some of his portraits from this period have been made available online including this photograph of seven young men taken in December 1864, courtesy of Brad Purinton’s Tokens of Companionship blog: The Lamoille Newsdealer of July 12, 1865 wrote that “N. L. Merrill, from Sprin[g]field, Vt., is now stopping at Johnson for the purpose of accommodating the public with any kind of a picture known to the photographic art. He has had a large experience in the business, and will be remembered by some in this vicinity as the man who first introduced a daguerreotype car into this part of the country. – He has erected a temporary saloon, which he terms a “Camp,” on the Common near Denio’s hotel, and commenced business in it on Monday last.” (p. 3) The camp was apparently well-attended and patrons’ “urgent solicitations” led him to stay in Johnson during August as well. Around this time, N. L. Merrill seems to have bought property in Johnson. He must have sold his Springfield business, because the back of a portrait taken by J. D. Powers of Springfield, Vt., says “We have also N. L. Merrill’s Negatives in preservation, and will furnish copies when ordered.” (eBay offering, August 2022) Merrill was on the move again. He ran an ad in 1866: “Mr. N. L. Merrill, the veteran artist, has pitched his ‘camp’ near the American House in this village (Hyde Park) and will remain four weeks for the purpose of supplying the people with Photographs, Ambrotypes, and Melanotypes, of the highest perfection. Copies from old and inferior pictures can be obtained and enlarged and finished in India Ink or colors, also card Photographs for the same. A good assortment of Phot[o]graphic Frames and Albums always on hand. His reputation as an artist is well established in this vicinity. Pictures can be made in cloudy as well as fair weather.” (Lamoille Newsdealer, June 6, 1866, p. 4) N. L. Merrill moved on to Cambridge Borough, VT a few weeks later. At times, he rented rooms rather than establishing a “camp.” A woman’s portrait recently offered on eBay was marked on the back “N. L. Merrill, Photographer, Rooms over Kinsley & Bush’s Drug Store, Cambridge, VT.” In April 1868, N. L. Merrill leased a photographer’s “saloon” in Barton Landing in northeastern Vermont. He was listed in the Vermont State Directory of 1870 in Johnson, though the 1870 census shows him in Montgomery, Vermont. (The entry listed Nathan Merrill, photographer, married to “Patience.” Presumably he was passing through town and the census taker did not work too hard on the details.) N.L. Merrill also had a studio in Dunham, in the Eastern Townships of Quebec where he was listed in Lovell’s Canadian Dominion Directory in 1871. The Brome County Historical Society holds a portrait taken by him there. In 1872, N. L. Merrill seems to have had a studio in Enosburgh Falls, Vermont, from which he moved on and a different photographer set up shop. A portrait posted online showed that at some point, N. L. Merrill also took pictures in Richford, Vermont. In the early 1870s, N. L. Merrill seems to have returned to Stowe, Vermont fairly often. According to the back of a portrait available online, he set up shop in Stowe with a company name of “Mt. Mansfield Picture Gallery.” (Another photo for sale on ebay showed the same gallery with a different photographer, so he may have bought out or sold to a photographer named O. C. Barnes.) In December 1872, N. L. Merrill closed his Stowe gallery for a few weeks and went to Rouses Point, across Lake Champlain in New York. The back of a photograph recently listed on ebay confirmed that N. L. Merrill indeed took pictures in Rouses Point. Merrill was in Stowe again in October 1873 but planned to pack up soon “and go where there are more faces.” (Lamoille Newsdealer, Oct. 15, 1873, p.4) In 1874, he reappeared in Stowe In May and September when the Argus and Patriot reported that N. L. Merrill was “again prepared to make those new style photographs.” (Sept. 3, 1874, p. 3) In addition to portraits, he took a series of Stereoscopic Views of Stowe Village, Mount Mansfield, Smugglers’ Notch and a number of nearby waterfalls. An advertisement for his gallery in Churchill’s Building in Stowe mentioned that he stocked frames, albums, brackets, knobs, and cords, along with a collection of stereoscopes and stereoscopic views. Unfortunately, there was quite a bit of competition in the “view” business, so it may not have been profitable for him. We have not found that he did any other series. The New York Public Library has a stereoscope view taken by N. L. Merrill available online, and the reverse side shows his other subjects. N. L. Merrill returned to Johnson repeatedly; by the 1870s, it was clearly his home base. In Dec. 1876, N. L. Merrill of Johnson was “taking all kinds of pictures at the photographic gallery of Mrs. B. W. Fletcher” in Waterville, VT. (Burlington Weekly Free Press, Dec. 15, 1876, p. 3) An ad in the April 25, 1877 Lamoille Newsdealer announced that N. L. Merrill would keep his Johnson photographic gallery and saloon open a few weeks longer. In July 1879, Merrill did a short stint in South Troy, Vermont, but then returned to Johnson. Nathaniel, “Photographist,” Prudentia, and daughter Mary were living there at the time of the 1880 census. The two photographs below have been made available online by Special Collections at the University of Vermont's Baily/Howe Library. Both have “Merrill, Johnson” printed on the mats. They were identified on the backs with a name, hometown, and “Classmate J. S. N. S.,” referring to Johnson State Normal School; its students would have been a good source of business for a portrait photographer. We found less frequent evidence of N. L. Merrill’s activities in the 1880s, but he was still at work. He set up a studio in Enosburgh Falls, Vermont in September 1883, but he was listed in the Lamoille County Directory of 1883 and the 1887 Vermont Business Directory as a Johnson photographer. In November 1885, daughter Mary was married to Hannibal Best at the Merrill residence in Johnson. A quit-claim deed dated Nov. 14, 1888 shows that Nathaniel, his wife Prudentia, her nephew Samuel H. Waters, and his wife Juliette sold lands and tenements in Johnson. (Three mortgages had been executed on the property/properties in 1865, 1869, and 1872.) N. L. Merrill was apparently still living in Johnson, however, while taking photographs in Waterville in Sept. 1889. In Feb. 1890, the St. Albans Daily Messenger reported that N. L. Merrill, who had had a photographic business in Johnson for many years, was moving to live with his daughter and her husband Hannibal H. Best in Enosburgh Falls. The News and Citizen reported that he was dangerously ill in mid-February 1891 and that he died in Enosburgh Falls on Feb. 26, 1891. Unfortunately, we have not found a death record or full obituary for him. A burial notice in the St. Albans Messenger on March 5 said that he had been an invalid for years, but according to an advertisement in the News and Citizen, he had been working as a photographer in Johnson as late as January 1890.

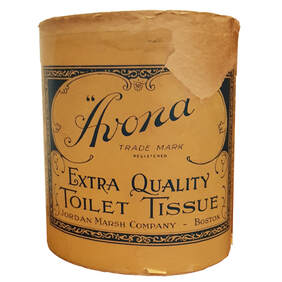

Back in Acton When we first found the flyers for N. L. Merrill’s daguerreotype saloon, we thought that he would be local and that we could easily track down his life story. What we discovered was Nathaniel L. Merrill, a Vermont photographer who had to be on the move constantly in the decades that followed 1856's saloon. We pieced together many of his movements after 1860 from digitized newspapers, records, and photographs, but we were not able to trace his origins. Different records gave his birthplace as Maine, New Hampshire or Massachusetts, and we found no source that mentioned his parents or siblings. Most of his early travels with his daguerreotype saloon in the 1850s are also unknown, including why he came to Acton (assuming our identification is correct). Any additional information would be appreciated. Clearly by 1856, the people of Acton, and South Acton in particular, could easily have had their pictures taken if they could afford it. One has to wonder what happened to the likenesses taken that winter; we would love to have scans of local pictures taken by N. L. Merrill. The Society and Iron Work Farm have rare pictures taken of local buildings lost to fire in the 1860s. They could have been Merrill’s work, or perhaps there were done by other itinerant photographers who offered their services in mid-nineteenth century Acton. It is even possible that we could have early N. L. Merrill pictures in our collection. Unlike paper photographs with mats that showed the photographer, location, and sometimes the subject of the picture, early photographs in their metal or leather cases were much harder to label. We have a collection of beautiful early portraits of unknown people done by unknown photographers; it is frustrating that no one labelled them while there was a chance of identifying them. (A selection is here.) Photography was new at the time; perhaps people simply did not imagine that eventually likenesses would survive but people’s memories would not. If your Acton ancestors’ likenesses or their photographs of local scenes are in your possession, we would be very grateful to add scans (or originals) to our collection. Please contact us. Sources Used (in addition to standard genealogical resources): 9/21/2021 A Different Kind of AntiqueIn recent months, much behind-the-scenes work has been going on at the Society’s museum buildings to improve exhibits for the day when we are able to be open again. Work is also progressing on improving our storage to make items more accessible in addition to being preserved and protected. In the process of digging into storage and less-accessed areas of our buildings, we occasionally come across a surprise. This summer, one of our volunteers uncovered this item, never accessioned into our collection, but a rare find nonetheless. The purchaser of this toilet tissue would never have expected it to elicit fascination from our volunteers, but disposable daily necessities seldom survive to become antiques. We do not know where the roll came from, but we did find that a trademark application was filed on November 19, 1925 for “Avona” printed on the diagonal in the font that is on our label. Jordan Marsh Company held the trademark for many years and periodically advertised Avona toilet tissue in the Boston Globe. Ads around 1950 featured pictures of the rolls that had quite a different look from ours, so we suspect that our roll was from earlier days. A May 2, 1927 ad mentioned a 1000-sheet package, not a roll. (page 4) In the November 10, 1932 issue (p.9), Jordan Marsh advertised a special sale of 24 1000-sheet rolls for $1, so that could be approximately the era of our find. The tissue came with options; one could buy white, orchid, rose, yellow, green, or blue. Jordan Marsh would fulfill orders by mail or telephone.

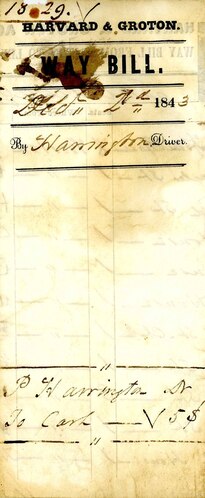

We never know what we are going to learn by volunteering at the Society. 1/19/2019 Sarah Skinner, Getting Used to Darkness The Society recently was given an 1834 letter that had been sold as a postage collector’s item, a “cover” that pre-dated the use of stamps. Folded, it was addressed to Abraham Skinner, Esq. of Brookfield, Massachusetts. Inside, the letter was preserved: Acton Feb. 8, 1834, Mr. Skinner, I have neglected, longer than I intended to do, to inform you of your mother’s health. She is pretty comfortable this winter, would be very, were it not for the continued pain in her eyes. She has not had the least perception of light for several months. Her situation is in many respects less uncomfortable since she has become more accustomed to perfect darkness. She grows familiar with the house, and walks with much less confusion, is some part of the time, able to busy herself with knitting, which she considers quite a privilege. She wishes to be affectionately remembered to you. I am much oblidged to you for the papers, which you had the goodness to send me. Respectfully yr Cousin, M. Faulkner One cannnot help being touched by the letter and feeling admiration for Mrs. Skinner who, while dealing with pain and disruption, felt privileged to be able to knit. We set out to learn more about Mrs. Skinner, her son Abraham, and the writer of the letter.

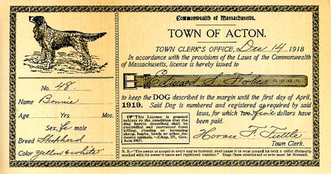

Mrs. Skinner and Her Family Abraham Skinner, Esq. of Brookfield, Mass. was born in Acton on July 25, 1789 to Dr. Abraham and Sarah (Faulkner) Skinner. According to Phalen’s History of the town of Acton (page 98), the father, Dr. Abraham Skinner, was Acton’s third physician. He had come from Woodstock, CT, for reasons we have not yet been able to discover, and started his Acton practice in 1781. He married Sarah Faulkner in March 1788. Sarah (or Sally) Faulkner was the daughter of Francis Faulkner and Rebecca Keyes whose large family lived in the landmark Faulkner House in South Acton. Francis was prominent in Acton. He ran the Faulkner mills, represented the people in the Provincial Congress of 1774 and the Committee of Safety, attained the rank of Lt. Colonel in the Revolutionary War, and served the town in numerous roles, including a 35-year stint as town clerk. According to Shattuck’s history of Concord and surrounding towns (pages 292-293), Francis and Rebecca Faulkner had eleven children. (We were able to confirm ten of the births through Acton vital records; one is harder to pin down.) Sarah was the third child. Dr. Abraham and Sarah Skinner had four children, Abraham (born 1789), Henry (born 1792), Maria (born 1794), and Francis (born 1797). Fletcher’s Acton in History gives two different identities for Dr. Abraham’s wife, an odd mistake given that Fletcher seems to have known Henry’s aged widow. Perhaps the doctor was married earlier elsewhere, but we found no record of it. All Acton records show that the wife and mother of Dr. Abraham’s family was Sarah Faulkner. We did not find any documentary evidence of Sarah’s life while she was raising her children during the 1790s and earliest years of the 1800s. Her husband does show up in local records. He received payments periodically for “doctering” the town’s poor, and in September 1792, the town voted upon temporarily opening a quarantine “house” for inoculating residents against smallpox under the direction of Dr. Skinner, provided that it could be done ”with Safty” for the townspeople. Dr. Abraham Skinner was apparently one of the contributors to the cost of a winning ticket from the Harvard College lottery in 1794. His share of the prize money has been said to have gone into building or improving a house for the Skinners’ growing family at what is now 140 Nagog Hill Road. Land records show that Abraham paid David Barnard on Sept. 5, 1786 for a 60 acre farm and the east half of the existing house on the property, plus a half interest in the barn, garden, yard, wells, and a “cyder mill” behind the house. On Sept 27, 1788, Dr. Skinner paid Reuben Brown for 18 acres of land and the other half of the house, barn and barnyard. Specifically excluded from the sale was a school house standing on the premises. Dr. Abraham Skinner became a charter member of Concord’s Corinthian Masonic Lodge in 1797 along with Sarah’s brother Winthrop Faulkner. [See Surette’s history of the Lodge.] Abraham was appointed to Acton’s school committee in 1799 and 1809 and to the large committee formed in 1805 to deal with the contentious issue of where to locate the new meeting house. He died in 1810. Records of the time did not mention the cause. Dr. Abraham’s estate inventory gives us an idea of the life of the household. The home farm was valued at $2,500, and there were fifteen additional acres of pasture land in Littleton and a pew in the Acton meeting house. The Skinners owned clothing, furniture, (a variety of beds, tables, chairs, and a bookcase), bedding and table linens, a woolen carpet, several looking glasses, a day clock worth about $30, spinning wheels, dishes, utensils, towels, table cloths, tools, chaises, a sleigh, a horse, harnesses, a saddle, cows, sheep, a cart and a plow. There is little evidence of a medical practice, not surprising given the state of medicine at the time. Dr Skinner did own a medical library. In addition, there were numerous debts to Dr. Skinner from townspeople. The estate was originally administered by Sarah’s brother Winthrop, but Henry took over by September 1814. Sarah Skinner was listed as the head of household in the 1810 census with two males between 10 and 25, one female between 16 and 25, and one other “free white person”. In May, 1811, children Henry and Maria (minors above the age of fourteen) petitioned the probate court to allow “Widow Sarah Skinner” to be their guardian. Son Francis made the same petition in April, 1812. Son Abraham had already left his parents’ household by 1810. According to Fletcher’s History (Biographical Sketches, page 1), Sarah’s sons Henry and Francis helped to run the farm for a while. Henry appears in Acton militia lists in the 1810-15 period, and Francis appears in 1815. In Feb. 1816, the town paid Henry Skinner for boarding John Faulkner for 8 weeks. During that year, Francis left to work in Boston. Henry eventually moved to Andover and opened a store there. No Skinner is listed as head of household in the 1820 Acton census, so we have to assume that Sarah was living with relatives by then. The actual sale of the Skinner farm to Charles Tuttle was not completed until 1827. Acton’s history books made no more mention of Sarah (Faulkner) Skinner. Skinner Voices, from Indiana Because Sarah Skinner disappears from Acton’s history books in the 1810s, the letter describing her later life is a wonderful addition to our Society’s archives. However, it turns out that ours was not the only letter from the Skinner family that survived. The University of Notre Dame Special Collections’ Manuscripts of Early National And Antebellum America contains a collection of letters to and from Abraham Skinner of Brookfield. A few of the letters were written by his mother Sarah. Given how seldom women's thoughts and actions were recorded in our histories, finding this collection was a wonderful surprise. Sarah's letters start in about 1806 and continue after she lost her husband. Sarah mentioned some news of family members, but what stands out most from her letters is how much she missed her son and wanted him to write and to visit more often. Her letters are a reminder of how difficult separation was for families of the time and how completely cut-off they must have felt when letters failed to arrive, sometimes for very long periods. We also learned from the Skinner correspondence that Henry was in Brookfield for a while in 1811 but then returned to Acton by early 1812. His letters show that he was trying to find work in a store in either location, clearly ready to move on from the farm. The Skinner collection also includes a March 1817 letter from daughter Maria Skinner, the only record that we have seen of her beyond the mention of her birth and death in Acton's vital records. Maria echoed her mother's yearning to hear from the men of the family, including Francis who had not been in Acton since the summer before. Maria, left at home, was feeling "allmost forsaken." She also mentioned that Sarah had provided lodging for "Mr. Potter" followed by another family, so we now know that Sarah had others in her household during the years after losing her husband. Who wrote the 1834 letter about Sarah Skinner? After researching Sarah's life, our next question was who, exactly, wrote the letter donated to our Society. “M. Faulkner” signed the letter to Sarah’s son Abraham as “yr Cousin.” On the reverse of the letter, in a very different hand, there is a notation: “Mary Faulkners Letter Feby 8, 1834”. Allowing for the possibility that the term “cousin” might have been used somewhat loosely, we could still narrow down the potential writers. We searched Acton’s Vital Records for “M” Faulkner births. Of the six births we found, five were Marys. Omitting details of our research here, we concluded that the most likely candidate was Mary, born Sept. 11, 1801 to Winthrop (Sarah’s brother) and Mary (Wright) Faulkner. This Mary actually would have been Abraham Skinner, Esq.’s first cousin. She lived to 1871 and never married, so she still would have had her Faulkner surname in 1834. We thought that our research would stop there, but our theory received a boost from a rich source that we did not expect to find. Sarah Skinner, a Woman of Note Researching Acton in the early years of the nineteenth century is made more difficult by a lack of available newspapers and very few surviving letters and diaries. However, sometimes one gets lucky. Not only did we come across the Skinner Family Correspondence at Notre Dame, but we found Sarah mentioned in two Boston newspapers after she died in 1846. Her death was briefly noted in Boston’s Emancipator and Republican (March 25, 1846), and the Boston Recorder (March 26, 1846) published a memorial tribute. Signed “W,” it was dated Acton, Mass., March 19th, 1846 and included a request that it be reprinted in other religiously-oriented newspapers in the Northeast. The writer felt compelled to write about Mrs. Sarah Skinner, described as “always polite, well informed, kind, lovely,” interesting, unwavering in her faith, and happy. When younger, she had liked to read, but having suffered greatly during the "complete destruction of her eyes," at the end of her life she was “stone blind.” Her hearing, fortunately, continued to be acute. She still enjoyed conversing, and her interest in life and her friends was undiminished. As we surmised from the 1834 letter, she did not complain about her life but found much to be grateful for. “Her only daughter was long since dead, but she had left grandsons, able loving and true; and she had a pious unmarried niece, who was altogether a daughter unto her, to the last.” The cousin of Abraham Skinner who wrote our letter, Mary Faulkner, was presumably this unmarried niece, daughter of Sarah’s brother Winthrop. We thought, when we started this research, that Sarah (Faulkner) Skinner had been neglected by history. We were delighted to discover that it was possible to learn something about her, a woman clearly remarkable for her fortitude. We also know from her own letters that she was human, sometimes lonely and sometimes anxious about her absent children. Many of Acton’s stories have been lost, but we are grateful to have found this one. As we begin the new year, we take this opportunity to express appreciation for people who donate items to archives and for organizations that work to preserve and share them so that others can learn about the past. In the context of Sarah Skinner’s story, we especially would like to thank the University of Notre Dame’s Rare Books and Special Collections for their assistance with our research. A recent project at the Historical Society has been to index a large number of letters and documents relating to Horace F. Tuttle (1864-1955). Researching his life led to an eye-opening record of service to the Town of Acton. Acton’s 1956 Annual Town Report paid tribute to Horace’s family upon the retirement on December 31, 1956 of Harlan Emery Tuttle from his position as town clerk. He had served for 15 years, following his father Horace Frederick Tuttle who served for 45 years (1896-1941) and his grandfather William Davis Tuttle who served for 41 years (1855-1896). Set against 101 years of Tuttle service to the town of Acton, our “large” collection of documents now seems like a tiny portion of the work done by the three generations of Tuttle town clerks.

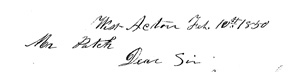

Of the items indexed so far, there are personal letters from family members, documents relating Horace Tuttle’s apple-growing and surveying businesses and his administration of estates, and documents relating to a few of his years as town clerk; genealogical inquiries, a request for help from a serviceman’s wife during World War 1, a list of Acton servicemen during that war, a draft of a letter written on surplus 1907 ballots, inquiries about cemetery plots, a request to open the library during the town fair, and much more. Sorting through them, one couldn’t help but wonder if there was anything Horace Tuttle didn’t do! 12/17/2015 Watch Your Assumptions - They're All RelatedThe letter by O. W. Mead described in the previous blog post yielded a surprising number of lessons for a note obviously written in some haste. It was addressed to Andrew Patch of Canaan, NH. The salutation, as shown above was:

Mr. Patch Dear Sir O.W. Mead briefly mentioned his recent local travels and the weather and instructed Mr. Patch to pay "Foss" and to hire him for future work. (Money was evidently enclosed.) Then the letter related the sensational local news item of the day involving the discovery of “F. Taylor.” It read, to someone used to today’s ways of conversing, like a letter between business associates, telling a story of local, but not personal, interest. That was the wrong assumption. As described in the previous blog post, research showed that “F. Taylor” was Franklin Taylor (1808-1849), son of Oliver Jr. and Elizabeth Fairbank Stone. The Taylor family of Stow and Boxborough was quite large. One of them was O. W. Mead’s mother Lucy - It turns out that she was actually the sister of “F. Taylor.” Further research showed that “Mr. Patch” of Canaan, New Hampshire was married to Marie Mead, daughter of Nathaniel and Lucy (Taylor) Mead. Marie was O. W.’s sister. O.W. Mead was reporting to his brother-in-law the discovery of his uncle’s remains. The moral of the story is that it is important to approach documents written in a different era with an open mind and an understanding of how people addressed each other. Reading the letter with a twenty-first century mentality led to completely inaccurate conclusions! 12/13/2015 F. Taylor Mystery Solved A letter in the Society’s collection raised curiosity recently. It was written by O. W. (Oliver W.) Mead , dated West Acton, Feb. 10th 1850, and sent to Andrew Patch of Canaan, NH. The letter related the gruesome discovery by “an Irishman” of the remains of [F. ?] Taylor “in a swamp a short distance from this place.” Finding out the identity of Mr. Taylor seemed as if it would be easy. It turned into a research project. Mr. Taylor’s first initial was not initially obvious, given somewhat difficult handwriting. Death records for early 1850 or 1849 in Acton revealed no Taylors. “A short distance” from West Acton could have been Boxborough, Littleton or Stow, but research in those towns, using various strategies, produced no results. Finally, an online newspaper search was successful. The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts, Friday March 8, 1850, page 4) picked up the story from the Boston Post that Franklin Taylor of Boxborough had been missing since June 1st of the previous year when he left home in the grip of delirium tremens and, as it turned out, committed suicide. The discovery was made in a wood lot near West Acton depot. The details match O. W. Mead’s letter. Published Boxborough records show a Franklin, son of Captain Oliver and Elisabeth Taylor, baptized in September, 1806. Numerous other Taylor children were born in Boxborough to Capt. Oliver Jr. and Elisabeth/Betsy. (Oliver Jr. and Betsey Fairbank Stone were married August 12, 1800 in Boxborough. Presumably, the “Jr” and “Capt” in Boxborough’s records were added to distinguish the couple from Oliver’s parents Oliver and Betty, but sorting out the family relationships needs to be done cautiously. ) The family seems to have moved to nearby Stow, as Franklin appears in Stow Tax Assessments of 1841, 1844, and 1847 and the 1842 Stow list of “persons liable to do military duty," along with other Taylor relatives. Franklin returned to Boxborough around 1847, as he appeared in the Militia roll for Boxborough in 1847 and 1848. There the record seems to end, at least in easily accessible online sources. Vital records, usually very helpful in Acton and surrounding towns, apparently omitted Franklin’s demise. Though learning the circumstances of Franklin Taylor’s death was not particularly happy, it did show the value of keeping and indexing old letters. Sometimes, local or family news reported in a letter can yield unique genealogical clues. It is tempting in this era of online searching to think that we can trace families without leaving our computers. However, archives may be holding a picture, a diary, a letter, or some other document that can open up new chapters of a family’s story. If you have Acton roots or connections, contact us; you may find information that is unavailable in other sources. |

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed