|

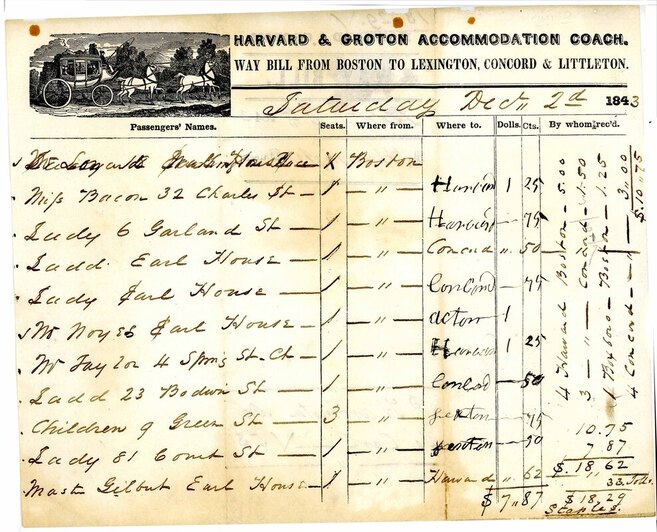

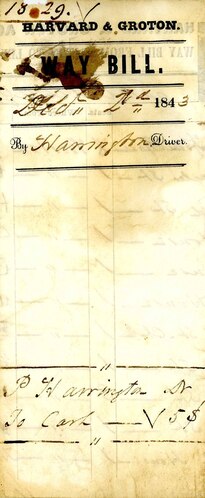

4/24/2023 Stagecoaches Through ActonOur document collection contains a way bill listing passengers who rode a stagecoach from Boston on Saturday, Dec. 2, 1843. Among the passengers was Mr. Noyes who caught the coach at “Earl House” and headed to Acton. The document is a souvenir of travel just before Acton’s transportation choices changed dramatically. Prior to the arrival of the Fitchburg Railroad in 1844, as Fletcher’s Acton in History tells us, travel to and from Boston “was slow and difficult. The country trader’s merchandise had to be hauled by means of ox or horse-teams from the city. Lines of stage-coaches indeed radiated in all directions from the city for the conveyance of passengers, but so much time was consumed in going and returning by this conveyance that a stop over night was absolutely necessary if any business was to be done. ... a visit to Boston before the era of the railroad was something to be planned as a matter of serious concern. All the internal commerce between city and country necessitated stage-coaches and teams of every description, and on all the main lines of road might be seen long lines of four and eight-horse teams conveying merchandise to and from the city. As a matter of necessity, taverns and hostelries were numerous and generally well patronized.” (p. 268) Coaches required fresh teams of horses at intervals, so stops were usually made every 8-12 miles. Acton had taverns before the stage routes (for example Mark White’s at 274 Great Road and Jones Tavern in South Acton), but as stage travel became more prevalent, taverns and inns multiplied as well. Shattuck’s History of Concord says that the first public stagecoaches came from Boston “into the country through Concord, in 1791, by Messrs. John Vose & Co.” (p. 205) Ads for stages between Boston “and the country north-west thereof” were being advertised in the Columbian Centinel in 1793, leaving from Charlestown and passing through Concord and Groton. Acton was not mentioned specifically, but presumably stages traveled via today’s Great Road, coming from Concord, through East Acton, by Nagog Pond, and on into Littleton. That route was noted as “Littleton Road” on a map drawn by Jabez Brown in 1794 and was also in early days referred to as the Groton Road. Like later decisions about railroad routes, decisions made elsewhere about stage and mail routes would have significant effects on businesses in outlying towns. The Columbian Centinel ran a series of proposals in 1794 that indicated that the mail route from Boston to Keene and other points in New Hampshire had not yet been settled. It would either go through Concord and Lancaster or Concord and Groton. Later, there seem to have been disputes among “interested persons” such as innkeepers about whether there was a significant difference in distance between the Groton-to-Lexington routes via Carlisle or Concord. (Green’s Historical Sketch, p. 193) By June 1810, the Boston Patriot was running ads for competing stage lines that explicitly mentioned Acton. Luther Carlton advertised the Concord, Harvard & Winchendon Stage that left Boston on Wednesdays & Saturdays at 7 a.m., passing through West Cambridge, Lexington, Concord, Acton, Boxborough, Harvard, Shirley, Lunenburg, and Fitchburg. (On Saturdays, it continued on to Ashburnham and Winchendon.) Return trips were on Mondays and Fridays. (June 23, p. 4) Meanwhile, a “new Arrangement of the old Concord and Leominster MAIL STAGE” was leaving Boston on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays at 5 a.m. going through Cambridge, West Cambridge, Lexington, North Lincoln, Concord, South Acton, Stow, Bolton, Lancaster, Leominster, South Fitchburg, Westminster, Gardner, Templeton, Gerry and Athol. The return stage left Athol at 4 a.m. on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, arriving in Boston in the evening. The latter ad noted that the meal stop was at the Hotel in Concord. (June 2, p. 4) On March 16, 1827, the Boston Traveler advertised that the Boston and Keene Union Stage Company ran a daily stage line leaving Boston at 5 a. m., passing through Lexington, Concord, Acton, Groton, Townsend, Ashby, Rindge (NH), Fitzwilliam (NH), Troy (NH), and Keene (NH), arriving at 5 p.m. in Charlestown (NH). Connections from Keene and Charlestown allowed travelers to continue on to points in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Saratoga Springs. “The Company have been to great expense in purchasing the best of horses and carriages and employing the most careful and obliging drivers, and have spared no pains in establishing the line that it shall not be exceeded by any other from Boston for dispatch and convenience of passengers. They have fourteen changes of teams between Boston and Charlestown, giving only about eight miles for each set of horses.” (p. 3) Stage coach stops such as those advertised by the Union Stage Company encouraged the growth of taverns and inns. Fletcher tells us that “in the east part of Acton, on the road leading from Boston to Keene, there were no less than four or five houses of public entertainment.” (p. 268) An 1831 map shows “Weatherbee’s” (65 Great Road), “Hatgood’s” (really Hapgood’s at 162 Great Road) and White’s (514 Great Road) taverns along Groton Road. The earlier White’s Tavern had been opened in 1755 and operated for a number of years, but it was not in operation in 1831. Fletcher’s History also notes that additional demand for taverns was from drovers who would accompany livestock to their summering pastures in New Hampshire. Wetherbee’s Tavern was well-known to drovers and drivers of baggage-wagons all the way to Canada. (Fletcher, p. 294)  Hosmer Tavern, 471 Mass. Ave., c. 1930s-1940s Hosmer Tavern, 471 Mass. Ave., c. 1930s-1940s Another stage route through Acton followed the Union Turnpike, although as originally surveyed, it had some steep grades farther west that were not popular with stage coach drivers. During the cash-strapped post-Revolutionary War years, the expansion of long-distance roads was often accomplished by for-profit ventures that would involve building a road and then collecting tolls, often at bridges. The Union Turnpike was approved by the Massachusetts Legislature in March 1804 and started operating in 1809. Joel Hosmer of Acton, seeing a business opportunity, enlarged his father’s house at 471 Massachusetts Avenue along the Union Turnpike route to serve as a tavern. (Joel Hosmer appears as one of the names attached to the Union Turnpike Corporation in the legislative act that established it.) The History of Harvard tells us that once Harvard got its own post office around 1811, the Harvard, Lunenburg and Winchendon stage would come with mail and passengers from Concord over the Union Turnpike. Those coaches would stop at a tavern in Harvard (the half-way point) for meals. Hosmer’s Tavern, like the Turnpike itself, was not a profitable venture. The Union Turnpike’s competitor route, the Lancaster and Bolton Turnpike, had easier grades. After the Union Turnpike’s bridge in Harvard was swept away by flooding in 1818, it was not rebuilt. The overly-steep grades were eventually abandoned and what was left of the turnpike in Middlesex County became a public road in 1830. Today, Acton’s Massachusetts Avenue (Route 111) follows the route of the old turnpike. During the 1830s, changes in transportation were happening elsewhere, but coaches kept running through Acton. The Daily Evening Transcript on Sept. 2, 1833 advertised the Lunenburg & Boston Mail Stage, leaving Boston on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays at 8 a. m., arriving in Lunenburg at 4 p.m., passing through Cambridge, Concord, Acton, Harvard, Still River Village, Shirley Village, and Shirley. One could buy tickets at Brigham’s, 42 Hanover Street, from proprietor William Shepherd. The Bay State Democrat ran an ad on June 3, 1840 for a new line of post coaches to Harvard, MA that would go from 9 Court Street, Boston, via Cambridge, West Cambridge, Lexington, Bedford, Concord, Acton and Boxboro on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. The Worcester Palladium advertised on March 31, 1841 proposed (presumably mail) routes, for two-horse coaches. The first was from Concord to Shirley by way of Acton, Boxboro and Harvard, 18 miles in four hours (Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, to leave at 2 p.m.). The return trip was to leave Shirley on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 7 a.m. The second route was from Worcester to Lowell, going through Boylston, Berlin, Feltonville, Stow, Acton and Chelmsford. We found no further information on the latter route. In terms of time and place, the ad most relevant to our way bill was found in the March 24, 1843 Boston Traveler. U.S. Mail Coaches would start out from Boston at 10 A. M., leaving from the office at 9 Court Street and 36 Hanover Street on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays for Lexington, Concord, Acton, Boxboro, Harvard, Shirley Village and Leominster Village. The return trip was from Harvard at 9 A. M. Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Our way bill was a Saturday run with 12 passengers (including some children). Mr. Noyes left for Acton from Earl House, listed in the 1842 Boston Almanac as Earl’s Coffee House, operating at 36 Hanover Street. The driver, P. Harrington, may have been Phineas Harrington who, according to Samuel A. Green’s Groton history, had a long career as a stage coach driver in the area. By the time Mr. Noyes took his trip to Acton in Dec. 1843, transportation patterns were changing. Railroads were already providing an alternative to stagecoaches elsewhere. The Fitchburg Railroad was completed to West Acton in the autumn of 1844, and Fletcher says, “that village became a distributing point for the delivery of goods destined for more remote points.” (p. 268) An ad from the Boston Courier on Oct. 28, 1844 tells us that “down trains” to Charlestown would leave West Acton at 7:36 and 10:51 am and around 5 p.m. Trains from Charlestown would leave at 8 a.m. and 1 and 4:30 p.m. After the 8 a.m. train arrived in Acton, stages would leave from there every day except Sunday for “Littleton, Groton, Townsend, Lunenburg, Fitchburg, Ashburnham, Winchendon, Westminster, South Gardner, Templeton, Phillipston, Athol, Mass.; Fitzwilliam, Troy, Swansey, Keene, Walpole, Charlestown, N. H.; Chester, Windsor, Woodstock, Rutland, Middlebury, Royalton, Montpelier, and Burlington, Vt.” There were other stages that only traveled three days per week for points in western Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, as well as Albany, NY. After the first train arrived in Acton just after 11 a.m., stages would leave for “Stow, Boxboro’, Bolton, Harvard, Lancaster, Leominster and Fitchburg” on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, and for Littleton and Groton on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. As the railroad was extended and lines proliferated, transportation patterns changed rapidly. Both South and West Acton kept growing thanks to the railroad, but Acton was only a stage hub for so many other destinations for a short time. Eventually, stagecoaches became a thing of the past. We are lucky to have in our archives a tangible reminder of those earlier days. Sources:

We are also grateful to the following websites for sharing information and sources on stage routes in other towns (all accessed April 23, 2023): Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed