Revolutionary War Soldiers Remembered Belatedly, Part 2 Research for our previous blog post on Revolutionary War soldier Isaac Ramsdell led us to a list of men recruited for service in the company of Capt. Wilbur Hudson Ballard (General Nixon’s Brigade, Col. Ichabod Alden) that included Acton soldiers Stephen Shepard and James Emery. The document stated that James Emery was killed in service on Oct. 8, 1777. We were very surprised to discover a second Acton resident who had died in service but was not on Rev. Woodbury’s list of local Revolutionary War soldiers and was not mentioned in our local histories. Unlike Isaac Ramsdell whose early life is still unknown to us, James Emery had clear Acton roots. James’ grandfather Zacariah was mentioned in some of the earliest town meeting records. (Though he is said to have lived in Chelmsford, he must have lived in Acton in some of those years, as he was chosen as highway surveyor, constable, and committeman in several town meetings). James’s father John was born in Chelmsford but settled in Acton on land owned by Zechariah. John appears in town meeting records starting in the 1750s. He served as highway surveyor and constable for the town. John and Mary Emery had a large family, most of whom show up in Acton vital records:

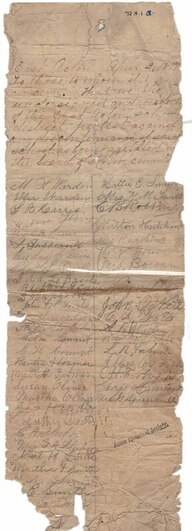

John Emery, James’ father, was listed as a member of Acton’s Alarm Company #2 in 1757, doing militia duty at the time of the French & Indian war. (There does not seem to be a record of his going to Canada during that time.) By the mid-1770s, the political sympathies of the Emery are quite clear. James’ brother Joseph was on the 1774 sign-up sheet of Acton men who formed a militia company under Captain Joseph Robbins, thinking themselves “ignorant under the Military Art and Willing to be Instructed.” John Emery appeared on Captain Joseph Robbins’ list of men who were under his command on May 15, 1775 and for the year 1776. (It is unclear from Captain Robbins’ list whether John Sr. or Jr. is on the list, or both. John Emery is the only name that shows up twice. It is possible that both father and son were meant, without specifying a “Jr.”, or that John Jr. did two different stints, or perhaps a different Emery was meant. Depending on the source, John Sr. is either credited with Revolutionary War service or not.) Fortunately, James Emery and his brothers did show up in other records. The compendium Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War has three entries for James. In one, a “James Emery, Concord,” was listed as “Private, Capt. Asahel Wheeler’s co., Col. John Robinson’s regt.; marched Feb. 4 [year not given, probably 1776]; service 1 mo. 28 days.” Given that he was assigned a town of Concord, this might seem to be a different James, but similar entries involve his brothers. John Emery, “Acton (also given Concord)” and Samuel Emery were credited with the same service. Acton’s John Oliver also served in that company and testified in his pension application that he was stationed in Cambridge at “the colleges” during that period. Another entry for James Emery came from a “List of men raised to serve in the Continental Army from Capt. Simon Hunt’s co., Col. Eleazer Brooks’s regt.,” dated Acton, Sept. 5, 1777. Simon Hunt mentioned:

The title of Simon Hunt’s list implies that all three men served at some point in Simon Hunt’s company, although we have found no other information about that service and have not seen an original or scanned copy of that list. The Massachusetts Line went through various reorganizations as the war progressed. During 1777, there was a great deal of organizational change and a focus on much-needed, longer-term enlistments. Records can be confusing as a result. Pay and muster records state that James Emory of Acton enlisted on April 14, 1777 for a period of 3 years. He served as a private in Capt. William Hudson Ballard’s co., Col. Alden’s (sometimes written Brooks’) regiment, joining the company on July 2. The regiment was assigned to the Northern Department and was at Saratoga. James, John and Samuel’s regiments were not involved in the first Saratoga battle but were in the second on Oct. 7, serving as part of Brigadier-General John Nixon’s Brigade under Major-General Benjamin Lincoln. Both the 6th Mass Regiment and the 7th took part in storming Breymann Redoubt (also known as Breymann's Fortified Camp) in that battle. Though the evidence is less clear, James’s younger brother Joseph seems to have enlisted in one of the shorter-term militia units that came to support the right wing at second battle of Saratoga as well. A return of men recruited for US service by Captain Wilbur Hudson Ballard (listed as Nixon’s Brigade, Colonel Alden) specifies that James Emery was killed on Oct. 8, 1777. (There was a clear distinction between men who were “killed” on Oct. 7-8 and others listed as “died” at other times.) Given that the second Saratoga battle took place on Oct. 7, either James was unlucky enough to be involved in late action, or injuries that he received in the fighting the day before proved fatal. He was 21 years old. After serving in the Revolution, James’ brothers John, Samuel, and Joseph and James’ brother-in-law Jonathan Davis (husband of Elizabeth), along with John Emery Sr., moved to Canaan, Maine and farmed near each other. James’ three other sisters married and settled in Maine. Three out of his four sisters’ husbands served in the Revolution. The family became actively involved in their new community, and local histories mention their Revolutionary War service. Back in Acton, when Reverend Woodbury made up his list of Revolutionary War soldiers, he omitted all of the Emerys. Perhaps no one was left in town who remembered them, or perhaps they were no longer considered “Acton,” because John Sr.’s land had become part of the new town of Carlisle in the intervening decades. Whatever happened later, James Emery was born in Acton, was counted as an Acton recruit, and died an Acton resident. Acton should remember his service. Sources Consulted:

By the time local historians tried systematically to document Acton’s Revolutionary War soldiers, quite a bit of time had passed. Rev. James T. Woodbury worked on the project during his pastorate in Acton (1832-1852). We do not know what written sources he had access to, if any. He did talk to townspeople and came up with a list of 181 men who had served in the Revolutionary War. Rev. Woodbury noted at the bottom of the list that he believed it to be incomplete, and research has shown that it was not perfect. (See blog posts on the service of Jonathan Hosmer and his son Jonathan, for example.) Occasionally, we come across a Revolutionary War soldier who lived in Acton and served for the town but somehow eluded Rev. Woodbury’s and later lists. This Memorial Day, we would like to recognize two such men, Isaac Ramsdell and James Emery. Both lived in Acton in the 1770s, were counted for Acton’s enlistment quota during the war, and died in service. Their relatives left Acton in later years, and by the time of Rev. Woodbury’s research, apparently no one was left to tell their stories. Isaac Ramsdell

So far, we have not discovered anything about Isaac Ramsdell’s early life. Complicating research, his surname has numerous variants such as Rams(dall, dill, dale, dle, doll), Ram(dall, dill, del, dle), Ramsden, or Ramsell. The first time Isaac appeared in Acton’s records was a marriage intention, filed in Acton on December 1, 1769, stating that he and Abigail Temple were both residents of Acton. Their marriage, performed by John Cuming Esq., took place in Concord on Dec. 21, 1769. A much later Acton record (difficult handwriting has been transcribed as “James” but seems actually to be Isaac) indicates that Isaac and his wife came to Acton from Concord in 1770. No land records were found for Isaac. Church records, however, tell us that three children of Isaac “Ramsden” and his wife were baptized in Acton in April 1775. Sarah, child of Isaac and Abigail “Ramsdal,” was baptized July 6, 1777. Dorathy Ramsdel, daughter of Isaac and Abigail, was baptized January 14, 1781. Acton records make no mention of Isaac’s death. Despite indications that Isaac may have come to Acton from Concord, we had no success finding Isaac there. Concord vital records make no mention of his birth. We did look for other Ramsdells (or variants) in Concord. A Mary Ramsdil married Ezra Cory in May 1766. Also, Acton records show a marriage between Elener Ramsdal of Concord and Eleazer Sartwell of Acton in 1755. Eleazer and Elener lived in Acton and had many children in the years leading up to the Revolution. If this were a family connection, it could explain why Isaac came to Acton. He may also have had Chelmsford connections; an Isaac Ramsdell owed a poll tax there in 1773. Following up on those potential connections, unfortunately, did not allow us to track down where Isaac came from. We first learned about Isaac Ramsdell’s war service from his widow’s pension application. An Act of July 4, 1836 finally made widows of enlisted men who served in the Revolution eligible to apply for pensions. By that time, many corroborating witnesses would have died or moved to unknown locations, so widows had to provide what information they could. When her pension application was being prepared in late April 1838, Abigail was 91 years and 7 months old. Hannah, eldest child of Isaac and Abigail, made declarations instead of her mother, testifying about what she knew of her father’s service. Though young during the war, she stated that she distinctly recollected “all the material and principal circumstances of her Father’s services and death.” She mentioned that she could “well remember” Capt. Isaac Davis calling her father “before he was up in the morning to go to Concord.” Hannah stated that her father was one of Isaac Davis’s Minute Men and that he participated in the “Battle of Lexington,” as the events of April 19 were known in earlier days, that he immediately enlisted for three years, and that at or before the expiration of his three years’ service, he reenlisted for another three years under Captain Joseph Brown of Acton. She believed that he served at Rhode Island, Ticonderoga and other places, that he was in the battle of Bunker Hill and at the taking of Burgoyne. She remembered his uniform and a fife that he carried in a side pocket. He was home on furlough in December 1779 but returned to active service in the spring. Hannah could “well recollect” the news of father’s death reaching her mother in Acton. Isaac was drowned at “King’s Ferrying Place” in 1780. Some of Hannah Ramsdell’s recollections are surprising, given what we know (or thought we knew). It has been assumed that all members of Isaac Davis’ company are known, unlike those of the Acton militia companies that served on April 19, 1775. Hannah was very young at the beginning of the war and could be forgiven for not remembering accurately. However, her mother would certainly have known who roused her husband that day. It is possible that they lived near Isaac Davis. Assuming that previous lists were correct in excluding Isaac Ramsdell, he probably was in one of the other two militia companies, most likely the “West” company under Capt. Simon Hunt. It is also possible that he went along with the Minute company unofficially, but it is surprising that others did not mention it, given the interest of local historians in that company. At a March 1, 1779 town meeting, article four asked if certain men’s taxes (all in military service at the time, including a very hard-to-read Isaac “Ramsdal”) could be abated for 1776. Whether this had anything to do with military service that year, we cannot tell. (The town dismissed the article.) However, from the records we do have, it would seem that Isaac’s service likely started before 1777. Simon Hunt filed with Col. Eleazer Brooks a listing (dated Acton, Sept. 5, 1777) of men who had been raised from his company to serve in the Continental Army. This indicates that those men had already served with Simon Hunt. Among them was Isaac Ramsdale, engaged for the town of Acton, who joined “Capt. Core’s co.” for three years or the duration of the war. On Feb. 26, 1777, James Barrett, muster master, reported to the State of Massachusetts Bay that he had paid a bounty to certain men since his last report. Among them were five from Captain Cory’s Company in Col. Kise’ Battalion, including Isaac Ramsdell. (The others were Jeremiah Temple, Isaac Russell, Silas Cory and Stephen Cory). Continental Army pay accounts state that Isaac served January 2, 1777 to December 31, 1779 in Capt. Job Whipple’s company of Col. Rufus Putnam’s Regiment and was credited to the town of Acton where he was a resident. Captain Whipple reported on clothing issued to his men in 1777; Isaac received a coat, vest, breeches, shirts, shoes and a hat. He also appears on muster rolls of Capt. Job Whipple’s Company, Col. Putnam’s Regiment, August 5, 1778 (White Plains), Sept. 9, 1778 and Oct. 1, 1779 (at Camp Bedford). Given the dizzying number of reorganizations of the Massachusetts Line during the war, it is not surprising that Isaac’s company membership is confusing. Jeremiah Temple’s records also show him both in Captain Cory’s and Captain Whipple’s companies. Hannah stated that her father served with Captain Joseph Brown. Two 1780 muster rolls from the 15th Massachusetts Regiment commanded by Col. Timothy Bigelow confirm that Isaac Ramsdell was a member of the company of which Joseph Brown was a captain. A muster roll dated July 28, 1780 from Camp Robinson’s Farm (covering the Jan.-June 1780 period) reported that Isaac was “on Command,” presumably doing special duty and not in camp that day. There were many camps in the Hudson Highlands whose exact location was nearly forgotten and had to be researched many years later. Apparently Camp Robinson’s Farm was a large encampment about 1.5 miles east of the Hudson River across from West Point at Garrison, NY. A muster roll taken at Camp “Tenneck” for the month of July 1780 but dated 31 August stated that Isaac Ramsdell died July 28, 1780. A further card in his file states that his service in the 15th Mass. dated from April 1779. He had enlisted for 3 years but died July 28, 1780. It was Hannah’s statement that specified that he drowned at “the King’s Ferrying place.” Kings Ferry was a strategically important crossing point between Verplanck’s Point and Stony Point on the Hudson River. It was the first narrowing point on the river north of New York City. It saw constant use and many historically significant events throughout the war. By October 1779, it was controlled by the Americans. There is no record of what Isaac Ramsdell was doing there while his company was being mustered about twelve miles north at Camp Robinson’s Farm on July 28, 1780. All we know is that something went wrong, and he drowned that day. Isaac Ramsdell left his widow Abigail with 3 small children and another on the way. According to Hannah’s statement and later records, the family consisted of:

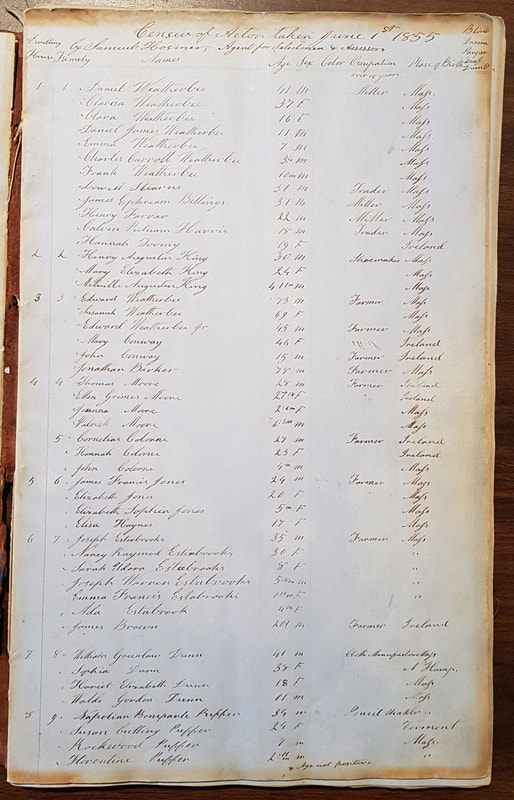

4/8/2024 The Page that was MissedResearch for our latest blog post involved searching the 1855 Massachusetts census for all Acton residents who were born in Ireland. Using one of the available online indices, a list could be generated quickly, and then linked images of the census forms allowed us to check each individual’s details and make sure that we had not missed anyone in town born in Ireland. Aside from some creative name-spelling and questions about ages, we thought we had a complete list of Acton’s 1855 Irish-born population. We should have known that the process was too simple.

A few years ago, the Society received a donation of a book containing a handwritten “Census of Acton taken June 1st 1855 by Samuel Hosmer, Agent for Selectmen & Assessors.” This 1855 census listing was entirely handwritten, not a set of filled-in census forms. Because we have easy online access to census images through genealogical websites, it had never seemed important to study our census book in detail. While working on the Irish data, however, we took a look at what was actually in the book. To our surprise, on the first page, in the first household, there was a young Irish woman who was not included in our list of Irish-born residents. Thinking that it was perhaps an indexing problem with the spelling of an Irish name, we tried searching the online 1855 census database for the Massachusetts-born individuals in the same household. They were also missing. Moving down the handwritten page, we found that none of the people listed by Samuel Hosmer in the first 6 Acton households, plus part of the seventh, was included in the online index. Three commonly-used online databases gave us the same result; none of them included people from the first 6+ households in our handwritten 1855 census book. The first person who appeared both on our book’s first page and in Ancestry’s 1855 census database was Emma Francis [sic] Estabrooks, age 1 year, 11 months. The online image of the census form showed that Emma was listed on the first line of a filled-in, preprinted Acton census form. There should have been a previous form that listed her parents, but when we tried to access the previous page, we found that there was no image other than the cover of a bound volume Census of Massachusetts 1855, Vol. 19, Middlesex Co., Acton to Cambridge. We had the same result using FamilySearch and another online database; presumably, they all used the same source. (Though stated sources and dates vary somewhat across the different databases, they seem to have come originally from microform/microfilm of the census held at the Massachusetts State Archives.) It appears either that the original filming missed the form that contained the first 6.5 households in Acton’s enumeration or that the first form was actually lost. Either way, the indices and digital images of Acton’s 1855 census that are being used regularly for research are missing 36 Acton residents. We offer here the missing page 1 of Acton’s 1855 census for everyone who is searching for the following 36 individuals. Some were life-long Acton residents, but others only seem to appear in Acton’s census records here. All listed individuals were born in Massachusetts, except as noted. Seven of the missed individuals were born in Ireland. (We included them in our blog post on Irish in 1850s Acton.) Samuel Hosmer’s 1855 Census of Acton: Dwelling & Household 1

Note that the name Weatherbee was more often spelled Wetherbee in Acton. The name Esterbrook(s)/Estabrook(s) is differently spelled even within the same family here and appears in different forms in various Acton records. Further research did not help us to confirm the Irish name Colorne and what other forms it might have taken. Records for other individuals in the 1850s yielded other possible names such as Coborne and Coline. 3/17/2024 Irish in 1850s Acton Source: NASA Earth Observatory Source: NASA Earth Observatory In honor of St. Patrick’s Day, we explored Irish immigration into Acton. The most useful starting point was the 1850 federal and 1855 Massachusetts censuses. Earlier censuses only listed the name of the head of households, usually male. The 1850s listings give us the name of every person in town, as well as their (sometimes approximate) age and birthplace. The population during the 1850s reflects changes in Acton caused both by Irish Famine immigration and the arrival of the railroad. The 1850 census of Acton listed 107 people born in Ireland, or 6.7% of the total population of 1,605. Twenty-five of the Irish-born individuals in Acton were female. (A clear error in the household of Ebenezer Davis Jr. was corrected in our statistics; research showed that the birthplace of Ellen Grimes and Charles Robbins was switched.). The 1850 Acton census gave no occupation for any female, so we can only guess what they were doing. Some women were living with a male who was probably the husband, sometimes with children. In other cases, females lived in a household of a seemingly unrelated family. They probably were doing domestic work. Of the 82 males born in Ireland, almost all who were of working age were laborers (71). Thirty-one were living on a farm and probably working there. Not one of the Irish laborers was listed as a farmer, a term that in the 1850 census apparently was reserved for those whose farm produced more than $100 of products. However, three of the Irish-born men owned real estate that included improved land and buildings. The town’s tax valuation for 1850 shows that John Grimes had 2 acres of improved land, Francis Kinsley had 1.5 acres, and Thomas Kinsley (listed in the 1850 census as Thomas “Wamsley”) had 3 acres. None showed up on the agricultural census for that year. Only three Irish-born men had occupations other than laborer. Twenty-six-year old Nathan Smith was working as a blacksmith for Jonas Blodget. Michael Phaelan was working as a “Switchman” for the railroad, an employer that provided opportunities to many Irish in the nineteenth century. It is very likely that some (or many) of the men listed as laborers worked for the railroad. Finally, Jerry McCarthy was listed as a Boarding House Keeper. Along with (presumably wife) Catherine and two children, he provided a home to eleven Irish laborers. In the 1855 Acton census, there were 111 Irish-born individuals out of a total population of 1,680. The Irish population percentage had not changed much, but the gender mix did. Forty-four were female (39.6% of the Irish-born population, up from 23.3% in 1850). Again, females’ occupations were not noted. Of the 67 Irish men of working age, 27 were listed as “farmer,” a term that seems to have been used in 1855 for anyone working on a farm. (Land ownership was not specified in this state census, although it can be discovered from other sources.) Two Irish-born men were listed simply as “laborer.” The 1855 census specified that 27 men were working on the railroad, almost all as “repairer,” although Michael Phelan was working as a “Switch Tender.” There were eight Irish-born men who had other occupations. Daniel McCarthy was working as a tailor. John Caully (name has possible interpretations such as Canly or Carelly) and Morris Sexton were apparently working at the flannel print works as a “flannel printer” and a ”dyer,” respectively. Michael Falan and Martin Fay were Wood Sawyers, and Thomas Kinsley was a Stone Layer. One has to wonder how the early Irish immigrants were received in Acton. Comparing the 1850 and the 1855 census lists, we found that many people from the earlier list had moved on by 1855. Given significant variations in ages and sometimes in names, it is impossible to match the two lists precisely, but the maximum number that we conjecture might possibly have been on both lists is 23 people. Whether that reflected the climate of the town or simply other opportunities elsewhere, we cannot tell. There may have been a variety of responses to the new arrivals. We do not have a local newspaper available until later, so surviving newspaper reports that were repeated in other places were likely to feature the worst. One such story that circulated in September 1849 accused Acton’s selectmen of shockingly uncharitable treatment of a family of Irish immigrants in crisis. After the story appeared in Boston papers and was picked up in others, Boston’s Daily Evening Transcript reported on an inquiry into the matter and clarified that the tragedy had actually happened in a different town and had not involved Acton’s selectmen at all. (The downside of our having access to digitized old newspapers is that we also have access to old rumors and reporting errors.) Whatever the welcome they received, Acton’s Irish residents proceeded with their lives after the huge upheaval of immigrating. Between 1848 and 1855, 37 children were born in Acton to Irish-born parents. Some Irish-born Acton residents had enough to show up in an 1855 Acton agricultural valuation:

Sources:

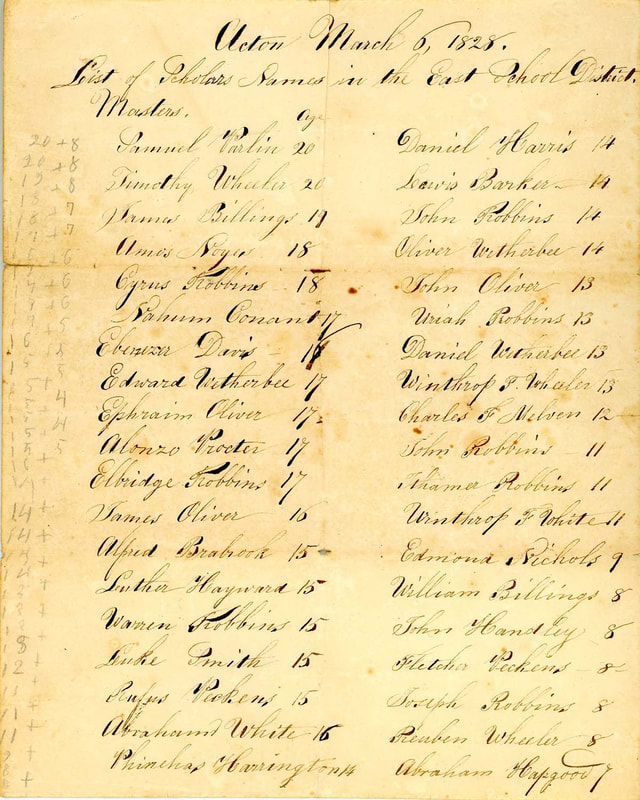

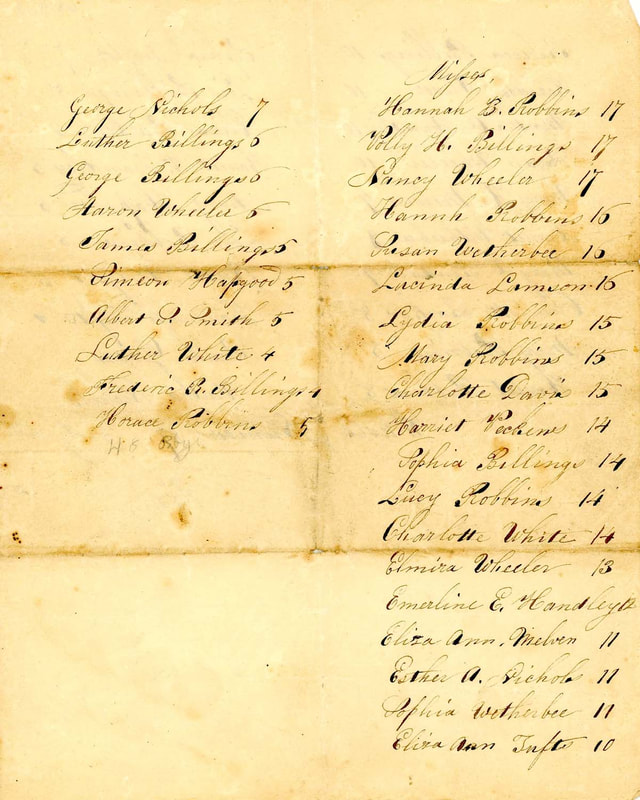

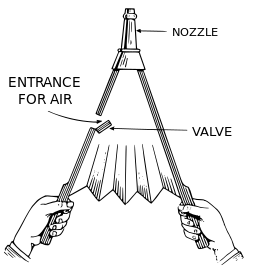

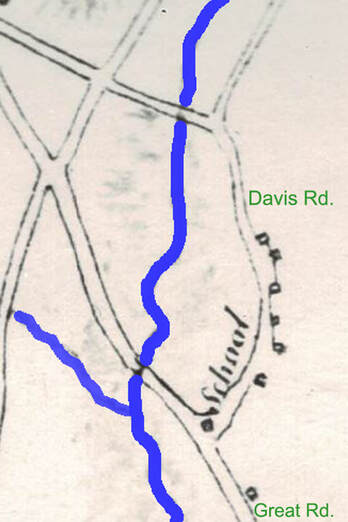

1850 Federal Census of Acton (online) 1855 Massachusetts Census of Acton (online) Census of Acton taken June 1st 1855 by Samuel Hosmer, Agent for Selectmen & Assessors (handwritten) Vital Records of Acton, MA Newspaper articles not actually describing an Acton event: Boston Courier, Sept. 13, 1849, p. 4 Boston Evening Transcript, Sept. 13, 1849, p. 1 The (Springfield) Daily Republican, Sept. 13, 1849, p 2 Boston Daily Evening Transcript, Sept. 20, 1849, p. 2 Salem Gazette, Sept. 21, 1821, p. 2 (quoting Boston Atlas) The (Gettysburg, PA) Star and Banner, Sept. 28, 1849, p. 5 Picture of Ireland courtesy of NASA Earth Observatory, image 49687 2/3/2024 Off the Track A scene that no doubt caused more pleasure for the children in the picture than the adults was captured by Maynard photographer Robert C. Swaney. The photograph came from South Acton and was clearly taken on the Boston & Maine Railroad. The photo is of a “switcher” (also known as a switching engine) that was used to move rail cars around railyards such as South Acton with its busy and complicated tracks. Whether or not the derailment happened at South Acton, we can only guess. We tried to find out more about this photograph. Researching the Boston & Maine railroad’s engine #1327 did not yield any helpful results. (Someone more knowledgeable might be able to date both the large lights on the front and the back and the painting style of the name and numbers on the engine and tender.) The next step was to find out more about the train’s mishap. Though we found many train accidents in the local newspaper as well as various mentions of a switching engine and crew, we did not find an article about a switcher derailment at South Acton. We did find one reported in Concord Junction news on the first page of the Jan. 4, 1911 Enterprise. We then researched the life of the photographer embossed on the mat of the photo. We found two pictures in the Maynard Historical Society’s digital archives that were by Robert Swaney, one of Maynard businessmen around 1910 and the other of the local Smoke Shop in 1911. Further research established the time period in which Robert Swaney would have been in Maynard taking pictures. Robert Clayton Swaney was born in West Lubec, Maine. His father George brought his family to Stow, MA about 1893. Apparently, they lived in the section known as Rock Bottom or Gleasondale that straddled the Stow/Hudson line. Robert’s mother, who lived to be 100, lived in Gleasondale for 60 years. Robert was a machinist living in Hudson when he married Hepsey Senior of Stow in June, 1899 in Gleasondale. In the 1900 census, he was living with his wife and his newborn son in Marlboro, MA. Marlboro’s 1905 directory reported that he moved to Stow, but a 1907 directory placed him in Ayer, MA, working as a motorman. (Apparently, he worked on a line from Ayer Junction to Lowell at one point.) In 1910, he was living in Hudson with wife Hepzibeth and two sons. Robert Swaney was listed as a Maynard voter on March 2, 1912, a “motorman” living and working in Maynard. A 1913 Maynard directory also placed motorman Robert C. Swaney in the town at 55 Acton St. We discovered from the Enterprise newspaper that he worked for the Concord, Maynard and Hudson Street Railway in 1915 (March 24, p. 9). An obituary in the Beacon mentioned that at some time, he worked on the line from Maynard to West Acton that passed through South Acton (Nov. 23, 1972, p. 14). We also found that a monograph in our collection about the Street Railway features a picture “from the collection of Robert C. Swaney.” When Robert registered for the draft in Sept. 1918, he was living on Haynes St. in Maynard, working as a machinist at La Point Machine & Tool Company in Hudson. A note on the 1912 Maynard voter list reported that Robert C. Swaney moved away from town in Jan. 1920. Research did not turn up any more connections to Maynard. In the 1920 census, Robert Swaney was living with his wife at 1 Bennet St., Hudson, working as a foreman at a machine shop. They were still there in 1930. In 1940, they had moved to Stow, and Robert was working as a foreman at a brake lining factory. Wife Hepzibeth died in 1948. In Oct. 1949, Robert married Mildred A. Gallant who was born in Littleton and had lived in Acton for many years. The 1950 census seems to have Robert and Mildred Swaney living with Robert’s widowed mother Laura both in Stow (High Street) and Hudson (64 Wilkins Street). (In both cases, his age was significantly understated.) A Hudson 1951 directory showed Robert living there with wife Mildred and his widowed mother Laura. He was superintendent at Standco Brake Lining Company. Robert Swaney lived for many years in both Hudson and Stow, but he died at a nursing home in Sudbury on Nov. 18, 1972. His wife Mildred had died that June. Having learned much more than we had expected about the photographer of our picture, including the fact that he had Acton connections, we found no evidence that he worked regularly as a photographer, or for very long. Robert C. Swaney would only have had a mat made with a Maynard address from, at the earliest, late 1910 to 1920. We are not sure where our picture was taken. It would be logical to think that if the accident happened in South Acton, Swaney might have taken the picture during his time working for the street railway that made its way regularly through South Acton (about the 1910-1918 period). One of the boys has a “C” on his sweater, which could imply a Concord location. On the other hand, Acton at the time was sending its high school students to Concord for their education; they, too, could have been sporting a “C.” If anyone has any further information that can help us to identify this picture, please contact us. 1/16/2024 One Crowded ClassroomAs mentioned in a recent blog post on the history of the East Acton school district, during the first decades of the nineteenth century, a one-room schoolhouse at the corner of today’s Great and Davis Roads served students from both North and East Acton. The result, especially in the winter months when farm work was not expected of older students, would have been crowding and a teacher with very little time for individual grades, much less individual students’ needs. Residents of East Acton campaigned for years to split the school. We recently came across a March 6, 1828 listing of all the students in what was then called the “East” School District. On it were the names and ages of 87 students, 48 “Masters” and 39 “Misses.” At a time when censuses listed only heads of household, this is a particularly useful document. In some cases, this is the only record we have found that shows a student’s presence in Acton. Given the age provided in the March 1828 list, some of the students were easy to find in the town’s published birth records. Some, because of a common name or an age that does not quite match dates in the records, were not so clear and needed to be followed up in other records. Baptisms were sometimes done well after birth, so the provided age was less helpful in identifying individuals in those records. In some cases, we could not find the students in any other Acton records, so we had to search farther afield and try to work back to an Acton connection.

Below is an annotated list of the 87 scholars in the March 1828 East Acton School with the results of our research into their identity. Overall, we found 42 whose name and age seem to match a person in Acton’s birth records and another seven whose age was somewhat off but who probably matched an Acton birth record. For 14 students, we found no birth record in Acton or elsewhere, but we did find a church/baptismal record in Acton that is probably the right person. (Some were baptisms done several years after birth, and some of those were born elsewhere). Research revealed five students whose later records reported an Acton birth, but there is no record of it at the time. We were able to find parents and a likely out-of-town birthplace for eight of the other students. The remaining eleven remain elusive. 11/25/2023 Two Enterprising EbenezersAfter over two centuries of ownership by the Davis family, Acton’s Ebenezer Davis, Jr. farm was sold in 1968. In an outbuilding locally known as “the Bellows Shop,” an astounding collection of documents, photos, and artifacts was discovered. Some of these items have now been donated to the Society, while others have found their way to the Concord Museum. These donations led us to research economic activities and business relationships in the Davis’ corner of East Acton during the first half of the 19th century. A number of Actonians left during that period to pursue economic opportunities elsewhere. Some, however, put their imaginations and energies to work on ventures in their hometown. Two such enterprising individuals were Ebenezer Davis Sr. and Jr. There have been several Davis families who contributed to Acton’s history. The story of the Ebenezers’ Davis family in Acton began with the 1738 purchase by Gershom Davis (also known as Davies) of about 664 acres in the northern part of Acton, including a house, barn, grist mill, and saw mill that had belonged to Thomas Wheeler. Over time, the land was divided among descendants who proceeded to sell, buy, and mortgage various pieces of the property. It can be bewildering to try to trace each person’s holdings. What we do know, however, is that Gershom’s great-grandson Ebenezer Davis Sr. (1777-1851) lived and farmed at approximately today’s 42 Davis Road on a site that was later Griffin’s Bellows Stock Farm and then Dropkick Murphy’s Sanatorium. Though the house no longer stands, part of its large chimney remains on the property, as well as a former barn (probably later than Ebenezer’s day) that has been converted to other uses. Ebenezer Davis Sr. was apparently a busy man. Deeds refer to him as a wheelwright (from 1800 to 1810, 1815), a yeoman (farmer, 1815, 1819 and later) and a housewright (1807-1808, 1817-1818). The Concord Museum now owns and has digitized ledgers belonging to Ebenezer Davis Sr. and his son Ebenezer Jr. from 1815 through 1853 (unfortunately with certain years missing). Though not complete, the ledgers show the variety of enterprises that Ebenezer Sr. was involved in. As deed research indicated, an early business of Ebenezer Sr. was blacksmithing and wheelwrighting. His ledger makes for somewhat confusing reading, because his thrifty reuse of pages means that the top of a page may relate to his early business and the bottom may contain notations from a decade or more later. However, the ledger does show over thirty customers in the 1815-1816 period who paid for jobs such as

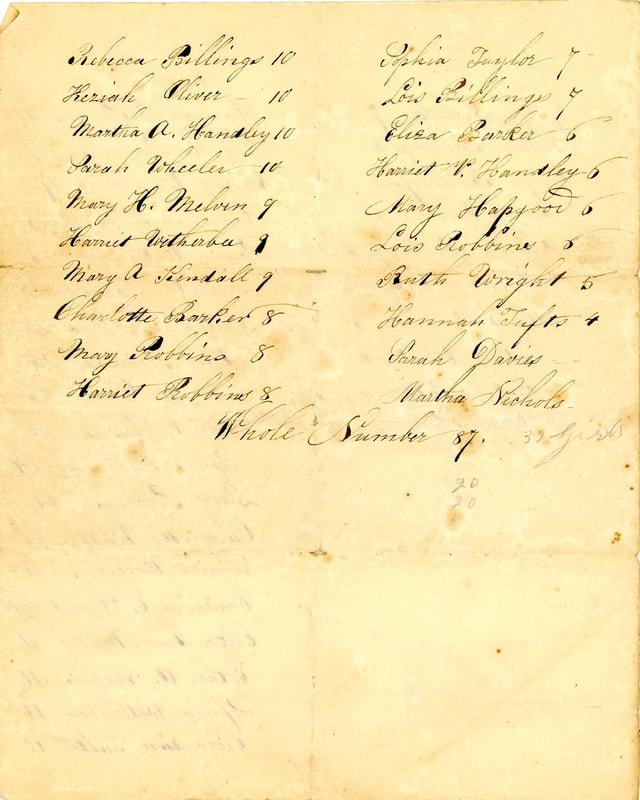

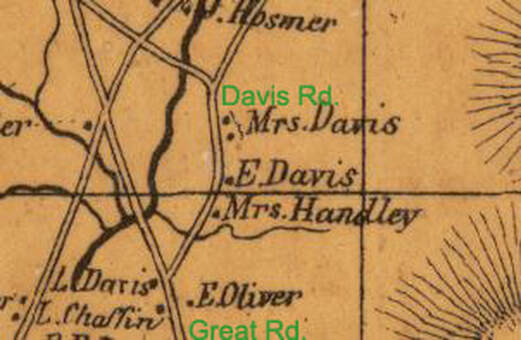

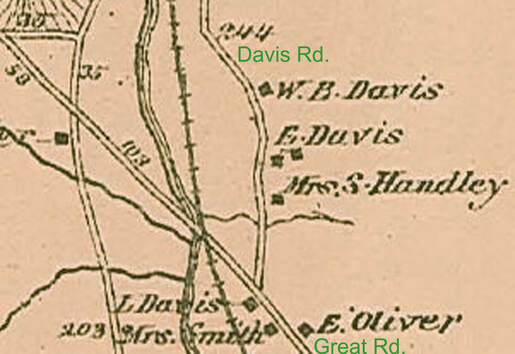

Neighbor Joel Oliver may have taken over the blacksmithing business after 1816. He was charged for coal, iron, and steel “for jumping axes” as well as leather aprons, the occasional tool, and food stuffs in the 1818-1826 period. (Jumping an axe was a term for replacing the bit/cutting edge.) Joel Oliver agreed to shoe Ebenezer’s pair of oxen and two horses for one year for $11 in January 1824. Ebenezer presumably continued with some work as a wheelwright, however, because he was paid for spokes and other work one would expect of a wheelwright later in the 1820s. The 1820 census shows that Ebenezer’s household included, in addition to 3 children, 3 males aged 16-26, 3 males 26-45, 1 female 16-26, and 1 female 26-45. Of these people, 5 were classified as being engaged in manufacturing and 1 in farming. The next household was Ammi Faulkner Adams with 3 people engaged in manufacturing. Unfortunately, the ledgers do not tell us what all of these people were creating. Many of Ebenezer Sr.’s ledger transactions in the 1820s and early 1830s seem to be related to his agricultural activities. He sold beef, pork, cheese, potatoes, corn, rye, cider and vinegar. He also sold hoop poles. In addition to his own farming, he pastured others’ cows and oxen, rented his horse and wagon or drove people himself, and took goods back and forth from Boston. Another set of transactions in the ledgers involved charges for a wide array of items beyond agricultural products. There were charges for cloth and for making articles of clothing such as a coat, pantaloons, shirts, vests and spencers (short-waisted coats). Boots and shoes were purchased or “specked” (a term for which we did not find a definition but guess it might mean repaired or resoled. One charge was for “leather to speck boots and heal”.) Other items were a silk handkerchief, shell combs, a “Parisol,” ribbon, a watch, a hat or bonnet, schoolbooks, a “Rithmatick,” and a great Bible. There were foodstuffs that would not have been produced on Ebenezer’s farm, such as sugar and molasses. On one page of the ledger, Abel Robbins owed Eben Davis for a large quantity of beef on Dec. 16, 1830 and a week later, Uriah Robbins was charged for broad cloth, buttons, skeins of silk, buckram, pasturing a heifer, a fine shirt, making a frock, and specking shoes and boots. These transactions raised a number of questions. Was Ebenezer Davis Sr. running some sort of store in his corner of East/North Acton? Was he personally creating clothing? Was he managing a clothing manufacturing business? None of these possibilities has been mentioned in town histories. Many of the accounts in the ledger were for people who were working for him, mostly close neighbors. In some instances, Ebenezer stated at the top of a page when an individual started working for him, and then listed charges. In other cases, he wrote a name and list of charges that were followed by an indication of the person’s employment, such as a list of sick days. In addition to charges for items such as clothing, the ledger shows that Ebenezer covered employees’ various needs for cash, such as at an election, at muster, at training, at Town meeting, for a mother or wife, “to pay the pedlar,” or “when you and Olive went to Concord,” and to settle bills, such as for Dr. Cowdry, "Luther Robbins for fish," or “your Taxes for 1827,” among many examples. At least two of the listed employees were noted to have lived in the Davis home for a period of time. Viewed in the light of an employment relationship, many of the ledger entries can be seen as Ebenezer Sr. making payments on behalf of employees and charging the payments against employees’ earnings. Unfortunately, the ledger is mostly silent about what Ebenezer’s employees actually did for him. It is possible that the making of shirts, spencers, vests and pantaloons was a Davis business, but it is also possible that Ebenezer was paying someone else on his employees’ behalf. Information about the Bellows Business, and More Questions The one business that later historians mentioned in connection with Ebenezer Davis Sr. and his son Ebenezer Jr. was the manufacturing of bellows. Unfortunately, information given in different sources about where and when the business operated is somewhat vague and not well-documented. The Davis ledgers and recent research paint a fuller picture than we had in the past and, inevitably, raise even more questions. Bellows would have been a common item in households and businesses in Ebenezer Sr.’s lifetime. They were used to direct a stream of air into a fire to increase the heat it produced. Bellows were manufactured by combining a wooden top and bottom with folding leather side pieces and attaching a nozzle through which air was forced as the handles were pushed together. When we started investigating the bellows business in Acton, information we had from previous historians was quite sparse. Online newspapers from the time make no mention of the Davis bellows business. Fletcher’s 1890 Acton in History said merely that “The manufacture of bellows was carried on extensively by Ebenezer Davis, senior and junior, for many years in the east part of the town.” (p. 266) Phalen’s History of the Town of Acton said that “At one time the aforementioned Ebenezer Davis manufactured bellows in a shop located on the William Davis place, later called the Bellows Stock Farm and later owned by Mr. and Mrs. Frank Griffin. The present occupant of the property is Mr. John Murphy. Eventually the shop was moved to the Eben Davis place where Dr. Wendell F. Davis now lives and where his father continued to make bellows.” (p. 156) There has been much confusion about this shop and the bellows business. The building in which the ledgers were found had come to be known as the “Bellows Shop,” but its exact history is not entirely clear. Given the fact that Ebenezer Jr.’s youngest son lived on the property and was probably the source of Phalen’s information about the building, it seems reasonable to assume that oral tradition in the family identified it as the bellows shop. In 1968, before the building was sold out of the Davis family and demolished, another discovery on the first floor was a crate, nailed shut, that contained hundreds of wooden bellows pieces, some already decorated, that were never assembled into finished products. Those pieces are now in the possession of the Concord Museum. By its architectural form, the “bellows shop” was clearly built as a dwelling house rather than a work shop. It is highly likely that this building was one of a surprisingly dense row of six houses shown on a c. 1831 map on what is now Davis Road. Deeds tell us that Ebenezer Sr. was involved in a number of real estate transactions, including purchasing a half share and then the remainder of the nearby “Ammi Wetherbee house” in 1808 and 1819. Though its exact location is hard to pinpoint from the deeds, Ebenezer’s ownership of that building raises the possibility that it was the one that eventually became associated with bellows production. By 1856, when Henry Walling mapped Acton, there were only four houses left on Davis Road, two owned by Ebenezer Sr.’s widow. An 1875 Beers Atlas map showed only one house was left on the former Ebenezer Sr. farm owned by William B. Davis, and Ebenezer Jr. had two houses, one behind the other. This seems to confirm Phalen’s assertion that Ebenezer Jr. moved the building from his father’s farm to his own. Tax valuations in 1872, 1875 and 1890 specify that Ebenezer Jr. owned a house and shop in addition to farm buildings. While many questions remain about the Ebenezers’ bellows business, the recent donation of Davis items to our Society, the information in the Ebenezer Davis ledgers, and research into deeds and other documents have given us some insights into their manufacturing activities. The first mention that we found of Davis bellows was in Ebenezer Sr.’s ledger. It involved Abraham B. Handley who had bought a new house on a small piece of Ebenezer Davis's land in 1826. On May 15, 1827, Abraham B. Handley was charged by Ebenezer $0.75 for three thousand Bellows Nails. On August 16, 1827, he was charged $0.50 to pay Ebenezer for carrying bellows to Boston. These entries imply that Handley may have been in the bellows manufacturing business first. However, another undated entry shows that Abraham Handley paid Ebenezer for 2 dozen 9-inch bellows and 3 dozen 5-inch pipes. (Given Ebenezer’s reuse of pages in his ledger, it is impossible be certain of the date, but another entry on the page is for Dec. 1831.) Could Handley and Ebenezer Davis Sr. both have been producing bellows? Was Abraham (eighteen years younger than Ebenezer Sr.) actually working for Ebenezer, or did they have a cooperative enterprise? The ledger also tells us that in Feb. 1827, Abraham’s 22-year-old sister Charlotte Handley began work for Ebenezer Sr. We do not know whether Charlotte was working in manufacturing or helping in the household. (We do know that she became Ebenezer’s second wife in 1839.) The only other early ledger entry mentioning bellows was in 1831 when Jonas Wood (another employee) purchased two pairs of swell-top bellows. Unfortunately, it seems as if pages from Ebenezer Sr.’s ledger either were removed or fell out. Ebenezer Sr.’s ledger has a decade-long gap starting about 1834 that ends with a partial transaction involving bellows, and then there are many other bellows transactions starting in 1844. Though a number of Ebenezer Sr.’s activities during the 1834-1844 period are missing, Ebenezer Jr.’s ledger, starting at the end of 1839, fills in some of the gaps. In early 1840, Ebenezer Jr. recorded buying Sheepskins, Morocco skins, scrap leather, 2 ounces of “bronze”, varnish, a varnish brush, and dozens of brass pipes. All of these were likely for bellows production. In March 1840, Ebenezer Jr. paid neighbor Ephraim Oliver for “swelling” 30 dozen boards, presumably part of the process of creating swell-top bellows. Starting in April, Ebenezer Jr. recorded sales of dozens of bellows of various sizes (flat, flat fancy, common, swell top, brass-nailed, and, later, oval and “custom”). He noted traveling to Boston, Salem, Lexington and Woburn, apparently to sell his products. Research in newspapers showed that his customers were mostly hardware merchants. The two Ebenezers seem to have made bellows separately but cooperatively. Starting In Feb. 1841, Ebenezer Jr. noted that he was delivering and selling his father’s bellows as well as his own. In March 1841, he noted that “George” had worked for “father” for seven days. Ebenezer Jr. also noted others who worked for him at times (without noting what they did) including Amos Handley, E Oliver, Kinsley, and A. Robbins. Ebenezer Jr.’s bellows sales were listed in his ledger consecutively until early 1844, after which there are only a few, sporadic entries in his ledger. Ebenezer Sr.’s ledger picks up again in 1844 with a partial entry (undated), followed by a Sept. 12, 1844 sale of 13 dozen bellows to Proctor and Butter. Ebenezer Sr.’s bellows sales continued, including some sales to his son. The last entry was on Nov. 8, 1849. Perhaps Ebenezer Sr. had run out of pages in the ledger, but there are no more entries after 1849. One point of confusion among local historians is how long the Davis bellows business actually lasted. Ebenezer Jr.’s ledger had some blank pages and some that were used for mounting newspaper clippings, so there was room to record more bellows transactions if there had been any. He did record several pages of charges to the account of Silas Conant from July 5, 1849 to Dec. 1853, none involving bellows. Those entries were mostly for agricultural products and loans of money. Toward the end of Ebenezer Jr.’s ledger is a listing of notes (loans) from 1845 (including some involving his brothers-in-law) and a few other transactions. There is one random mention of bellows without a date or a customer at the back of the book, but there is no evidence from either Ebenezer’s ledger that the business continued beyond 1850. Ebenezer Sr. died in 1851. His probate inventory listed bellows and bellows stock worth $150, the highest-value item in the listing aside from real estate and bank stock. Ebenezer Sr. also had many items and products related to his farm, including animals and swarms of bees. There were “shop tools,” “wood in shop,” “lumber in shop,” and “old lumber in old house,” but we have no other information about what those buildings were used for. It could reasonably be conjectured that since the “old house” contained “old lumber,” perhaps it could have functioned as a workshop for fabricating the bellows. Bedrooms on the second floor may have been used to house workers on the farm. Phalen indicated that Ebenezer Jr. moved the “bellows shop” building onto his own farm and used it to continue bellows production. An 1855 manufacturing census listing tells us that Ebenezer Jr. did carry on making bellows at least that long; he was listed as selling $300 of bellows that year and employing 2 hands for 3 months. We have not found evidence of his bellows business after that. Ebenezer Jr.'s Other Businesses Ebenezer Jr. certainly did not stop moving. Searches in online newspapers for mentions of Davis bellows yielded instead the insight that Ebenezer Jr. was a proud promoter of his agricultural products. The Boston Cultivator reported on Oct. 7, 1843 that Ebenezer Davis of Acton was in the nursery businesses, “bringing forward a good number of trees, though none are yet fit for sale.” In November 1845, Ebenezer Jr. advertised in the Cultivator that he had about 25, 000 New England-adapted apple trees, from one to two years growth from the bud that had been “budded by my own hands on seedling stocks, and grown on dry light sandy soil.” He offered a number of varieties including Baldwin, Greenings, Russetts, Hubbardston, Nonsuch, Lyscom, Porter, Fall Pippin, Danvers Winter, a number of “Sweet” varieties (Orange, Russett, Newbury, Andover), and more. Potential customers were invited to his Acton nursery to inspect his stock. An ad that ran in Spring 1847 was similar except that he was offering 30,000 trees with one to three years growth from bud. He also mentioned that growing them in dry, light, sandy soil ensured “a good supply of excellent roots.” (Massachusetts Ploughman, April 17, 1847). Apparently, farmers sometimes sent produce to newspapers for review. Ebenezer Davis sent the Cultivator several varieties of apples along with detailed comments on the different varieties written by his brother-in-law Harris Cowdry that were published on Nov. 13, 1847. On January 27, 1849, the Massachusetts Ploughman reported that the Middlesex Society of Husbandmen and Manufacturers had appointed a committee “to examine Farms, Reclaimed Meadows, Compost Manure and Fruit and Forest Trees.“ Twenty-eight farmers, including Ebenezer Davis, Jr., had applied for prizes for the best farm. The committee visited the farms and awarded second place to Ebenezer Davis, Jr. Helpfully, the newspaper used Ebenezer’s application to describe his 140-acre farm. Sixty acres were woodland, thirty were pasture, and fifty were under cultivation. His soil was light and sandy. In 1847, he raised corn (producing over 400 bushels) on ten acres, among which he also grew beans and pumpkins. He had recently broken ten acres on which he raised 154 bushels of rye, and he raised 200 bushels of oats on six acres. He raised 500 bushels of potatoes, but half of the crop was diseased. He cut thirty tons of hay, kept cows that produced milk and butter in excess of the needs of his family, and raised hogs in the winter. He also had at least a horse and a pair of oxen and wintered others. He had devoted two and a half acres to his Nursery business. Ebenezer stated that he had hired help equal to three men for eight months (at $15 per month) and one man at $10 per month for the rest of the year. In the months after his application, Ebenezer Jr. had raised his barn 18 inches and put a cellar under it (half for manure storage and half for root crop and fruit storage), set out 200 apple trees, and built 30 rods of stone wall. When the Committee visited his farm in September 1848, he had sixteen acres of corn, two of potatoes, and two of rutabaga, having also raised four acres of oats and cut forty tons of “English Hay” and four of “Meadow Hay.” “About fifty acres of his farm, being chiefly worn out and stony pasture, Mr. Davis purchased in 1845. Of this portion, he had ploughed and brought into a tolerably productive condition, sixteen acres.” Ebenezer Davis Jr. farm pictures taken by Robert I. Davis c. 1890 As if Ebenezer Jr. did not have enough going on in the 1840s, he had bought the home farm of the late William Stearns down Great Road in 1845. The land had once belonged to Mark White Jr. Ebenezer Jr.’s description indicated that the land was worn out, but it included a section of Nashoba Brook (downstream from the Davis farms and the original mill site purchased by Gershom Davis). According to an 1848 deed obtaining water-flowing rights from Luther Conant who owned the land immediately upstream, Ebenezer Jr. built a dam across the brook in 1845. Ebenezer built a large mill that would utilize the water power in 1847. According to a 1969 article by Brewster Conant, Ebenezer kept another ledger or journal that documented the purchasing of materials for the mill, the digging of the cellar hole in July 1847 and construction into September of that year. Apparently, on October 1, 1847 William Schouler moved in to operate a print (flannel) works, and Benjamin Davis later operated a sash and blind business at the site. The Conant article is the only source we have found about this additional ledger. Ebenezer Jr.’s ledger (owned by the Concord Museum) has a list of his debts in Spring 1845, presumably because of the purchase of the Stearns property. Building the mill was probably expensive. Ebenezer Jr. mortgaged 100 acres of his farm to his brother-in-law Harris Cowdry for $1,000 in 1849 (with an outstanding mortgage to Keziah Stearns dated June 16, 1845.) In 1850, Ebenezer Jr. sold most of the Stearns land on Great Road to Robert Boss of Charlestown. (See blog post about Captain Robert Boss). Ebenezer Jr. kept two acres for the mill and at least part of the mill pond. Ebenezer reserved the right to cross Boss’s land to the Davis mill and factory and the right “to flow his pond over the said land to the height and in the manner said Davis and his lessees have hitherto flowed the same.” (Managing the flow of water would be critical to the successful operation of the mill.) In the 1850 valuation, Ebenezer Davis Jr. was one of the larger taxpayers in town, owning valuable buildings and tied for having the second-most acres of improved land. Despite the fact that he clearly had water rights for his mill, he was not taxed for a “water privilege,” which, along with the deed to Robert Boss, suggests that he had leased the mill usage to someone else (probably William Schouler, a non-resident whose assessment included a water privilege). Though some have suggested that Ebenezer Jr. built his mill for his bellows business, we have found no evidence that that is true, and town histories do not raise that possibility. In 1852, Ebenezer started petitioning the town to lay out a road past his mill so that he would not have to cross Robert Boss’s land. It took several attempts to get the town to fund it, but in 1854 today’s Brook Street was laid out between Great Road and Main Street, passing right by Ebenezer Jr.’s mill site. The 1860 tax valuation assessed Ebenezer’s “Mills, water power, &c.” at $2,000. Ebenezer Jr. held onto the mill until 1865 when he sold the site to Martha Ball. The deed of sale did not specifically mention a residence, only “buildings thereon,” and a mill in particular. However, two of the town’s warrant items dealing with Ebenezer’s petitions specified that the road would pass by Ebenezer’s “house and mill” or “house and Factory,” so it seems that the house on the site dates from 1852 at the latest. Presumably he rented it out, as there is no evidence that he ever lived in it. Back on the Farm Whatever Ebenezer Davis Jr.’s other activities were, he kept innovating on his farm. The Worcester Palladium of Sept. 23, 1857 reported that sugar cane was being grown in Acton by Eben Davis who had two acres’ worth and planned to extract the juice for sugar. Ebenezer Jr. continued displaying his farm produce at agricultural fairs. His tempting clusters of Sweet Water grapes at the Middlesex Agricultural Society’s exhibition were mentioned in the New England Farmer on Sept. 28, 1861. The Lowell Daily Courier of June 22, 1869 mentioned Ebenezer Davis had sent luscious strawberries from Acton. “Mr. Davis is well known as a successful horticulturist, and he has for many years been a large contributor to our agricultural exhibitions.” On Sept. 6, 1871, Eben Davis of Acton was noted in the Daily Evening Traveller for displaying a fine basket of fruit at the New England Agricultural Society’s annual fair. Never one to miss an opportunity, after the railroad came through East Acton, Eben Davis advertised in Boston’s July 13, 1872 Daily Evening Transcript “Summer Board in Acton,” offering accommodations for up to four people at a pleasant location near a depot. We did not find much mention of Ebenezer Davis Jr. in later newspapers. One might have assumed that the busy Ebenezer had finally slowed down. However, perhaps he had more to think about close to home. On Oct. 11, 1873, 62-year-old Ebenezer Davis Jr. married 23-year-old Mattie/Minnie Snow. She was born either in Germany or Massachusetts, apparently to W. and Sophie Snow. So far, genealogical research has turned up no clues about Minnie’s ancestry and where exactly she came from (and when). The couple settled on Ebenezer Jr.’s farm and had son Wendell F. Davis on Dec. 25, 1876. Wendell F. Davis was the last of the family to live at the Ebenezer Davis Jr. farm. Ebenezer Davis Jr. died July 20, 1890 in Acton. Fortunately, his grandson Robert I. Davis visited Acton and took pictures of the farm that have been donated to our Society. He also took pictures of people, presumably family members, whom we are trying to identify. More Davis Information Needed We know that as late as the 1960s, other documents existed that might shed more light on the lives and businesses of Ebenezer Davis Sr. and Jr. In addition to the Ebenezer Jr. ledger/journal that mentioned the building of the factory in 1847, there was also a journal kept by Eben H. Davis, son of Ebenezer Jr. We have only a partial transcription of that journal. It would be very helpful to have access to those documents to learn more. In addition, we have a number of photos from Eben H. Davis’s son Robert for which we do not have identification. Family photos probably exist elsewhere that could help us to identify people in the pictures. If you know more about this family or have items that could be shared, we would be grateful to hear from you. Please contact us. Some Sources Consulted

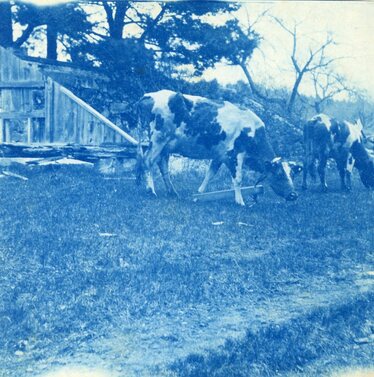

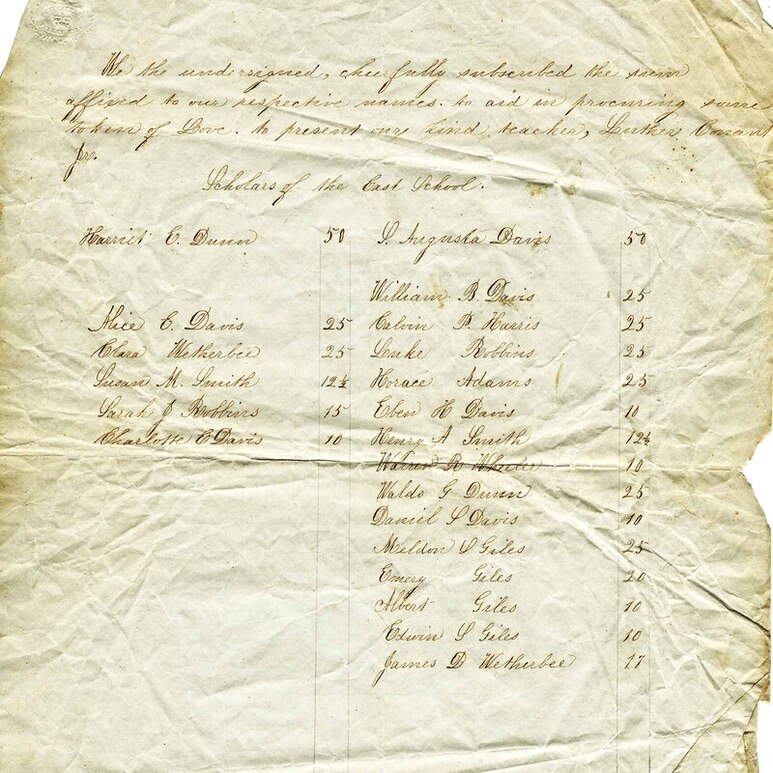

10/23/2023 East Acton’s Wandering SchoolhousesPreparing for the Society’s latest exhibit on the history of Acton’s schools has led to a flurry of research into some of the lesser-documented schoolhouses in town. East Acton’s schools have been surprisingly challenging to pin down. East Acton was not consistently treated as a distinct school district. Its schoolhouses were used for a relatively short time and then sold off for other purposes, sometimes to be moved down the street or even out of town. In addition, some of our most helpful sources on school history were written by people from other parts of the town; East Acton school information has proved harder to verify. In Acton’s earliest years as a town, individuals were paid to keep a school, presumably in their own house or sometimes in a privately-built schoolhouse. During the 1740s-1760s, the town was divided into a varying number of school districts - first three, then six, then five, then six again. In 1771, the town decided to build (or buy) schoolhouses. One of the existing schoolhouses was on today’s Strawberry Hill Road, perhaps at about today’s #13. (Though that location has been suggested on a historical map from about 1890, so far, no early deed or map has been found to pinpoint the exact location. We only know that it was “near Solomon Burgess” who lived on the north side of Strawberry Hill Road past its intersection with today’s Esterbrook Road.) A vote in May 1795 affirmed (briefly) that this school was going to stay in service, although town meetings’ frequent reconsidering of school locations complicates the job of understanding school history. In the late 1790s, there was also a schoolhouse standing somewhere near the corner of Main Street and Harris St. that would have served North Acton. In November 1800, the town voted to pay Daniel Davis for building a new school at the corner of Great Road and what is now Davis Road. Unlike many reconsidered decisions, this vote apparently led to actual building, because in December 1800 the town debated how they would use the newly built schoolhouse. The issue was whether they would send students from the East and North districts to the new school on Great Road or keep the students in separate districts. They voted to combine the North and East school districts into the new schoolhouse and sell off the old schoolhouse on Strawberry Hill Road and the one around today’s Harris St. The schoolhouses were both sold to David Barnard in Dec. 1800; their eventual fate is unknown. According to an 1849 school report, the 1800 combined schoolhouse was square, four-roofed and one-storied, similar to one that had been built in the town center, also by Captain Daniel Davis. The schoolhouses were painted red with white window trim and Spanish brown roofs in about 1803 (but not before a reconsidering vote on the roof color). The combined school district was not universally favored. The idea of splitting it up again was debated and dismissed in 1803 and 1818. In 1820, John White Jr. and others offered to raise the money independently to pay for a schoolhouse in their part of the district. Evidently that did not pan out, because in 1824, the town again was asked to split the district and elected a committee to look into the matter. In May 1826, the town voted to to purchase land and build two new brick school houses in the “east part of Acton.” Shortly thereafter, they reconsidered their decision. Bricks had been bought already and were given to the Selectmen to dispose of. (This required discussion at two additional town meetings and a second vote in 1827.) The debates continued. In 1832, John White and others tried to opt out of the combined district; that option was also dismissed. So many reconsiderations happened that it is tricky to understand exactly when the issue was finally resolved. In May 1839, the town agreed to make North and East Acton separate districts and to furnish them with brick schoolhouses. The old schoolhouse was to be sold. The North School seems to have been built promptly. Perhaps with too much optimism, it was decided that the East school would be built after agreement was reached on where to site it. There has been quite a bit of confusion among local historians about this school, certainly understandable given the town’s voting record. Some seem to have decided that the brick schoolhouse was never built in East Acton (including Phalen, author of a town history), but that idea is refuted by later records. In April 1841, the task of finding land for the East Schoolhouse was delegated to the selectmen. Although the warrant for the May 1841 meeting asked the town to reconsider that vote, the “decision” at that meeting was to postpone the reconsidering discussion indefinitely. The selectmen seem to have gotten on with the job, because on Sept 20, 1841, William Billings sold the town a piece of land for the new schoolhouse, about 3.5 square rods of land on the north side of the “town road from Acton meeting house to Nathan Brooks” (Strawberry Hill Road) for twenty-five dollars. The site of the brick schoolhouse was shown on four different maps that were drawn up during the school’s period of service. All the maps place the brick schoolhouse on the north side of Strawberry Hill Road, roughly opposite today’s #13. The April 1849 school report describes the new school: In the place of the old house on the great road are built two substantial and convenient brick houses, capable of accommodating fifty scholars each. They have good woodrooms and clothes rooms, and are furnished with black boards and Mitchell’s large map of the world; these last were purchased by subscriptions of the friends of progress in the district. These houses were built at a cost of $525 each, exclusive of the land and its preparation. Sadly, so far, no photograph has been uncovered of the brick East School building. The wooden 1800 schoolhouse eventually migrated up today’s Davis Road and became the second story of an outbuilding on the Ebenezer Davis Jr. farm. A photograph taken by a Davis descendant in the 1890s shows the square schoolhouse installed above a structure with wide doors apparently used for storage. A 1968 picture shows the old schoolhouse above what by then was Wendell Davis’s garage. It is still there today. Acton School Committee reports are available back to the late 1840s. One can learn about the progress and failures of each school and its teachers. They can make enlightening reading. It was customary to hire a female teacher for the spring and summer terms but to hire a male teacher, often a college student trying to supplement his income, during the winter term. The 1860-1861 report informs us that as an experiment, Susan Augusta Davis, who had been a student in the East Acton brick school herself a few years earlier, taught there the entire year. The result: The Winter School was an experiment. It proved a very successful one. The committee believed this school sufficiently civilized and humanized to be well managed by an intelligent female teacher.... We think the work of this teacher day by day, equal to any other in this grade of school ... If we can find such female teachers as Miss D. – and there are many of them – we can have at least one-third more school for the same money heretofore expended for male teachers, some of whom, doubtless, came here mainly to recruit their worn bodies, or fill their empty purses. (School Committee Report 1860-1861, page 21.) It was nice of Miss Davis to teach more hours in the East Acton schoolroom and save the town money.  April 1897 Petition April 1897 Petition New Becomes Old Unfortunately, one generation’s “substantial and convenient” building can turn into a later generation’s “smaller” and “inconvenient.” The brick schoolhouse got hard use. As early as 1862, some were advocating for new school buildings in town, but resources were extremely strained by “this grievous war.” No building was done at that time, but the school committee mentioned that “if a change of house is really needed in any district, it is in the East. Their house is more worn, smaller and more inconvenient in proportion to the number of scholars than any other in town.” (1861-1862 School report, page 20) It was not until the 1870-1871 report that a “nice and commodious" schoolhouse had been built. It was a wooden building at about today’s 209 Great Road (around the corner from the Strawberry Hill Road location). The next few years saw wooden schoolhouses also built in the South, West, Center and North districts. The c. 1841 brick schoolhouse was sold in 1870 to Henry Brooks who owned the abutting land. From 1875 and 1889 maps, it appears that he used the building as a paint shop. Ida (Hapgood) Harris, a teacher in the East Acton school in the 1890s, wrote a brief history of the Acton schools. She stated that the East Acton brick schoolhouse had stood on the left side of the road as one was heading away from Great Road, but by the time she was writing in 1937, it was no longer standing. The 1870 wooden schoolhouse was used through Spring 1897. By that time, views of education were changing. Classrooms in which one teacher taught up to eight grades were no longer in favor with educational experts. Apparently, not everyone agreed. It took several years of persuasion by the School Committee and others to make a change. Part of the problem was transportation. Residents from East Acton in June 1896 petitioned to use the funds being spent on the East School to pay for transportation of its students to the Center School. The town refused. This may explain why, in advance of the April 5, 1897 town meeting, a number of East Acton residents signed a protest petition against closing the East Acton school. Whether or not the petition had its intended effect, the Town finally voted to pay to transport the East Acton scholars. The East School was closed and its students were transported to the Center school starting in Fall 1897. (The North school followed in 1899.) The East schoolhouse was sold off. It went to Isaac R. Beharrell, a carpenter and contractor who moved it to West Concord and apparently used it as an office for his business there. We have not yet found out what eventually happened to that East School house. Does it still exist somewhere in West Concord? Was it later torn down? Does anyone have a picture of it during its time in Concord or while it was in East Acton? Please contact us if you can help. Vestiges of East Acton's Schools The Society owns some items related to the East Acton school district in addition to the 1897 petition pictured above. A listing of all students in the "East" district is discussed in a separate blog post. Another document was produced by early-1850s East Acton students, tallying up contributions toward a gift for their teacher Luther Conant, Jr. The Society also owns two large keys, both of which were said by the donors to have unlocked an East Acton schoolhouse. Both had connections to the Henry M. Smith family of Brook Street. A large iron key was donated by the wife of Henry M. Smith’s son Charles; she said that it unlocked an East Acton schoolhouse. A brass key engraved with “Wm. B. Davis” had a tag on it (in Henry’s daughter Martha’s handwriting) stating that “This locked the door of the old brick school house in East Acton.” The brass key was found in Martha Smith’s house at 260 Great Road (torn down decades ago to make way for a shopping center). The tag would seem to be a definitive identification for the brass key, except that consultation with an architect knowledgeable in local history and building practices indicated that the brass key was more consistent with an 1870s door lock, while the larger iron key would be a more logical fit with an 1840s lock. Note that William B. Davis was the school committee member responsible for the East School at the time of transition from the brick to the wooden schoolhouse. He probably had a key to both schools. Both keys seem to have ended up in the Smith family. As mentioned, we have no photographs of the brick East Acton schoolhouse. The Society does own photos that we believe, for numerous reasons, are of the 1870 East Acton schoolhouse. It is in keeping with all of our adventures in the East District that the identification was not simple. The best-identified photo included schoolchildren. The back of the photos says (probably written at least in part by a Society volunteer):

Fall 1889 East Acton School Harris St. Danny Wilson age 9 Effie Wilson Age 6 Gift to the Library by Mrs. Bertha Wilson Joslin, 3 Bow St. Concord, Mass. We are very grateful to Bertha Wilson Joslin for her donation. We believe that it solves our photo identification problems, despite the fact that someone gave the wrong address for the East Acton School. (Harris Street was for some years the site of the North Acton School, never the one in East Acton.) To confirm that the photograph was, in fact, East Acton’s school, we researched the family of Danny, Effie, and Bertha Wilson. They were all children of John Dwight Wilson and Agnes Maria Andrews who came down from Maine (where Danny and Effie were born). John took a job as a prison guard at the Concord Reformatory in 1887. At first, our research made us think that we might never prove where they lived in Acton and where their children would have gone to school. Our late 1880s maps seem to focus on owners, not renters, and we did not find the Wilsons. There is no 1890 census to help. The 1890 town valuation shows that John Wilson was not a property owner; his name was on a list of people who only paid poll tax. Luckily for us, however, another record exists. On August 2, 1889, Agnes Bertha Wilson was born to parents John and Agnes. Unusually, the town clerk that year listed in birth records the section of Acton in which the parents lived, instead of simply writing “Acton.” The Wilsons in August 1889 were indeed living in East Acton, meaning that their children would have attended the East Acton school on Great Road, and we had an identification for the schoolhouse. Finally identifying East School pictures because of Bertha Joslin's donation is a reminder that our ability to answer questions about Acton’s people and history is often dependent upon whether or not someone happens to have donated an item that gives us the clues we need. If other photos of the East Acton school (and other Acton scenes) still exist, having copies in our archives would be a big help to future researchers. Sources Consulted

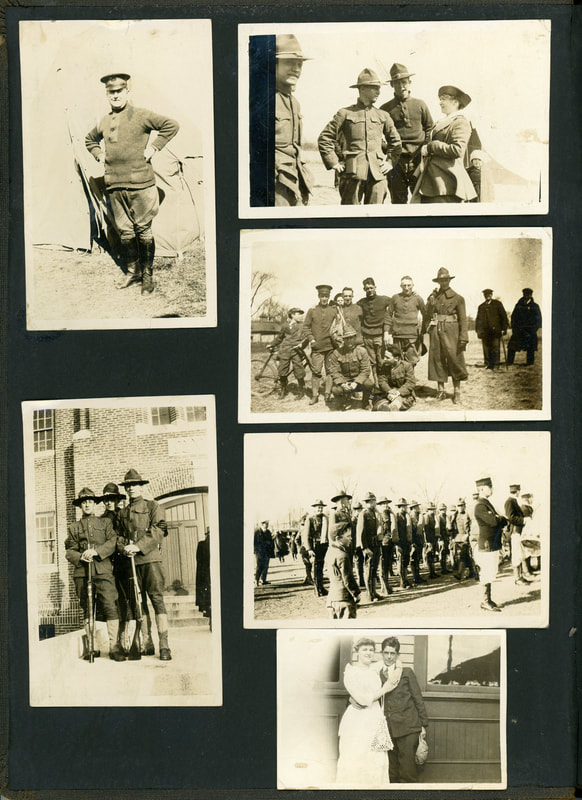

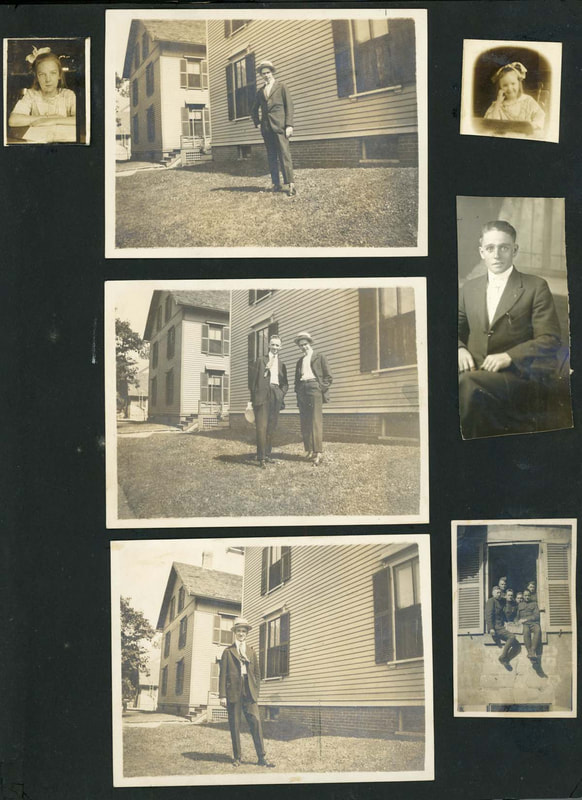

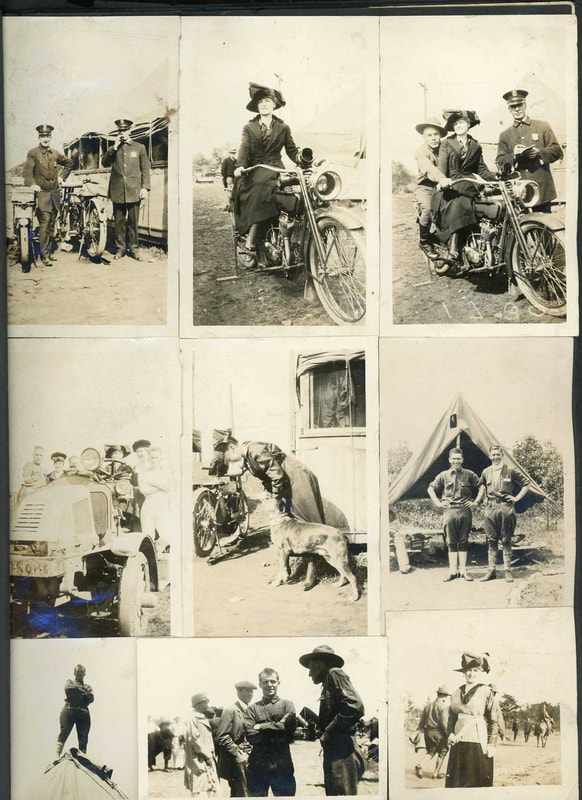

8/8/2023 WW1-Era Photo Album DonatedA donor just brought to Jenks Library a World-War 1 ere photo album that had been in the possession of a member of the Fullonton family of South Acton. No photos in this album are labelled, unfortunately. It is not yet known whose album this was originally, but we were able to put together some clues to help narrow it down. There are many pictures of soldiers in uniform as well as of others, undoubtedly family and friends. Some of the pictures may have been taken earlier. There are only a few clues about where the photos were taken or of whom:

To see more pages, see the full scanned album, available in our Unidentified Photos Section:

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed