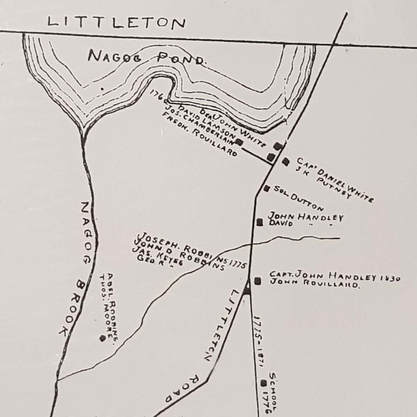

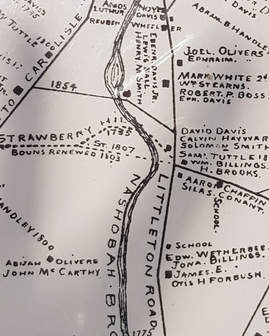

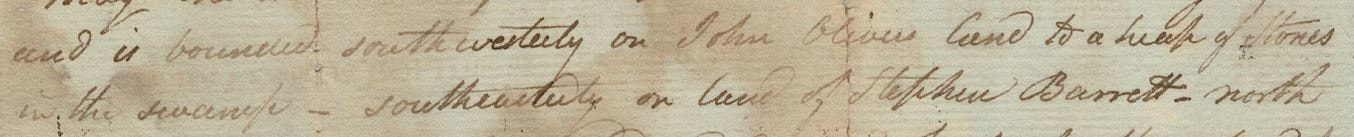

Family researchers sometimes find pre-1850 US federal censuses to be frustratingly sparse, but they can yield useful discoveries. Perusing the 1840 census, we discovered that it listed Acton’s pensioners from the Revolutionary War. Among them we found John Oliver, age 92. Curious about him, as his name was not as familiar as the minute men of April 19, 1775, we traced him through existing federal censuses, military documents, and Acton town records. In the 1790 census, John Oliver’s household was listed in the “free white” column, with one male aged 16 or over, one male under 16, and five females. In 1800 and 1810, John Oliver’s household of five was listed in the column for other persons (i.e., not considered white, not slaves, and not “Indians not taxed”). The ages and gender of household members were not specified. In 1820, the household consisted of a free white male and female, both age 45 or older, with one person engaged in agriculture. In 1830, John Oliver’s household members were all listed as “free colored persons”; three males (one each in the age categories 10-23, 24-35, and 36-54), and seven females (two under 10, two between 10-23, three between 24-35, and one each between 36-54 and 55-99). (Oddly, this does not seem to include a male as old as John Oliver himself; there is not enough information to sort out whether it was a simple error or something else.) Finally, in 1840, John Oliver was listed as a 92-year-old military pensioner in a household of five “free white persons,” one male in his nineties, one female in her forties, and three children under the age of ten, two boys and a girl. Though official records were inconsistent in classifying John Oliver’s race, they were remarkably consistent with respect to his Revolutionary War service. It is very well-documented, partly because he lived long enough to be eligible for a military pension and partly because he served in several companies for which written evidence exists. His 1832 pension application contains the record of John Oliver’s testimony in open court about his Revolutionary War service as well as corroborating statements from those who knew him. John Oliver started his Revolutionary War service at the North Bridge in Concord as a member of Acton's militia. (The Old Colony Memorial, May 15, 1824, p. 1, quoting the Concord Gazette, stated that he was a survivor of the Concord Battle.) John Oliver said nothing in his pension statement about serving on April 19, 1775. That was not an unusual omission in pension applications where emphasis was often put on later Continental Army service, according to George Quintal, Jr., author of Patriots of Color at Battle Road and Bunker Hill. John Oliver did state that at the end of April 1775 he enlisted at Acton, was stationed in Cambridge at “the colleges,” participated in Battle of Bunker Hill, and was moved to Winter Hill, serving for a total of eight months. (Locations are shown at the top left of a 1775 map.) His officers were Colonel John “Nickerson” (Framingham, actually Nixon), Lt. Colonel Thomas “Nickerson” (Framingham), Captain William Smith (Lincoln), 1st Lt. John Hale of Acton (actually Heald, probably the court clerk’s error), and 2nd Lt. John Hartwell (Lincoln). This shows up in Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War (MSSRW), a massive undertaking by the Secretary of the Commonwealth in the 1890s and early 1900s that pulled together extant written records to try to document military service. It corroborates John Oliver’s service in Captain William Smith’s Company, Col. John Nixon’s 5th regiment, with an enlistment date of April 24, 1775 (v. 11 p. 639). As he stated, he stayed after the original enlistment term of 3 months and 15 days had expired, as he showed up on a September 30, 1775 company roll. In John Oliver’s pension application, Solomon Smith of Acton, age 78, confirmed both John Oliver's membership in Capt. William Smith’s company and his eight months’ service. Smith mentioned officers Col. John “Nickson” of Framingham and 1st Lt. John Heald of Acton. Lt. Heald actually commanded the company at Bunker Hill, as Captain Smith was ill. John Oliver stated that he enlisted in February 1776 for two months and was stationed in Cambridge at “the colleges,” serving in the company of Captain Asa Wheeler (of Sudbury) in Col. “Roberson’s” Regiment. In the pension application, James Wright of Carlisle, age 78, confirmed Oliver’s Feb. 1776 service in that company. MSSRW (p.639) similarly shows that he served in Capt. Asahel Wheeler’s Company, Col. John Robinson’s regiment that marched Feb. 4 (year not given), service 1 month, 28 days. That service was precipitated by the need in early 1776 to strengthen the American position around the city. The culmination of that effort was the evacuation of the British from Boston on March 17, 1776. John Oliver next enlisted in Acton in September 1776, serving for two months and participating in the Battle of White Plains in Col. Eleazer Brooks’ Regiment, Capt. Simon Hunt’s company. Solomon Smith confirmed that 1776 service in his deposition, and MSSRW (p. 648) showed that John “Olliver” of Acton was with Captain Hunt at White Plains. It is clear that John Oliver was at the battle, but, not all sources agree on what Brooks’ regiment did at the battle. According to some, they were in the heavy fighting at Chatterton Hill in the White Plains battle on October 28, 1776. They had apparently been sent across the Bronx River to occupy the hill but did not have time to create more than the most quickly-formed defenses before the fighting began. Accounts vary, but it seems that the primary defensive structure for John Oliver’s unit was a stone wall and that the Americans did not have artillery support to match their opponents'. The fighting against both British and Hessian forces was brief but intense, and the Americans retreated. (Thomas Darby was also in Captain Hunt's company and was killed in the battle.) Town histories mentioned that the company fought bravely. John Oliver stated that around April 1778, he enlisted at Acton for three months, but “owing to circumstances he hired one [_ben?] Leighton to go as a substitute for him for the term of one month.” After the month, John Oliver went to Cambridge where Leighton was stationed and served until the expiration of the three-month term. His officers were Col. Jonathan Reed (Littleton), Capt. Harrington (Lexington) and 1st Lt. Elisha Jones (Lincoln). This was the only service for which John Oliver seems to have lacked corroboration in 1832. The pension application reported “the only evidence that he can obtain would be from one Ephraim Billings whose mind is very much broken he is unable to give his deposition upon that account.” (Ephraim Billings was the sergeant of that company.) MSSRW (v. 11, p.647) has an entry that John Olivers of Acton was on a list of men detached from Col. Brooks’ Regiment to relieve guards at Cambridge (“year not given probably 1778”) and was reported as belonging to a company commanded by Lt. Heald, Jr. of Acton. According to a muster roll dated May 9, 1778, Col. Jonathan Reed of Littleton was in command of a detachment in Cambridge. Capt. Daniel Harrington and 2nd Lt. Elisha Jones served under him there, so John Oliver may well have been transferred to their command in the spring of 1778. Finally, in 1780, John Oliver enlisted at Acton for six months’ service in and around West Point. He said that he served in Col. Brooks’ Regiment under Capt. White and Ensign Levi Parker (Westford). MSSRW (v. 11, p. 639) places him in Captain William Scott’s company, marching out July 22, 1780 and serving six months. Perhaps he was transferred; the Continental Army seems to have undergone various reorganizations over time. Several extant lists show John Oliver as a six-month volunteer in 1780. One list describes him as 23 years old, 5 feet, 6 inches tall, complexion dark, engaged for the town of Acton. He was present at Camp Totoway, Oct. 25, 1780. In the pension application, Charles Handly of Acton, age seventy, testified that Oliver enlisted into the continental service for six months in 1780 and first marched to West Point, from there to New Jersey, and then to West Point and then was discharged in Patterson’s Brigade. In May, 1782, the selectmen of Acton billed the Commonwealth of Massachusetts for wages paid to John “Olivers” for this service. (The town had neglected to include his wages on a previously-submitted pay roll.) In his pension record, John Oliver stated that he lived in Acton when he first enlisted and had lived in Acton since the war. Based on later records, he apparently had a young family during the war years, though their birth records are lacking. Acton’s records do show that in 1788, town meeting voted to abate his tax rates along with Peter Fletcher’s (no reason noted) and that in 1789, he was paid for working at Laws Bridge. In a less-than-appealing practice of earlier days, in 1790, the town of Acton “warned out” residents who had “lately” moved into town, a practice that was meant to assign responsibility for the poor to the towns from which they came. A fairly long list of people was warned out in 1790. Among those was John Oliver, “who is residing in Acton Labourer who has lately come into this town for the purpose of abiding therein not having obtained the Towns Consent" and therefore that he should "Depart the Limits thereof with his wife and their children.” Given his service in the Revolution, this seems to be an act of eye-opening ingratitude, but it was standard practice of the day. He was not the only veteran on the list or the only one who had been in town since before the Revolution. Duly warned about a lack of safety net, John Oliver continued to live in the Acton, apparently near the family of John Handley (who lived not far from Nagog Pond on the road to Littleton). In 1800, the selectmen laid out a “bridle way to accomidate John Oliver by said Olivers and John Handleys” that was accepted as a town “way” in May 1801. He was paid for “lowering a bridge with Stone near Mr. Jonathan Davis” in 1802. He showed up in town expenditures for 1813 - 1815 being compensated for supplying wood and taking care of people (apparently relatives) who were on the town’s needy list due to sickness or injury. Finally, in the 1830s, he was able to receive a pension for military service. He seems to have achieved old age in good health and outlived most of the Revolutionary War generation. John Oliver was reported to have been one of the survivors of the Concord battle who attended two celebratory dinners in 1835, the town of Acton's Centennial on July 21, 1835 and Concord's 200th anniversary celebration on September 12, 1835. (See the Columbian Centinel, August 12, 1835, page 1, the Norfolk Advertiser, August 15, 1835, page 1, and Fletcher's Acton in History, page 264, part of Hurd's History of Middlesex County.) John Oliver died in November, 1840. His probate record included a petition to the court that Francis Tuttle be made administrator of the estate. It was signed by “all the sons & daughters of Mr. John Oliver Late of Acton” and included three heirs: Abijah, Joel and Fatina [Fatima]. (Presumably there could have been other children who died earlier; Abigail Triator, daughter of John Oliver, died in Acton Oct. 13, 1819, for example. Without birth records or detailed census data, it is very difficult to put together the whole family.) John Oliver left behind a home farm with a house, barn and about 14 acres of land (appraised at $300), a cow, hay, lumber, corn, potatoes, pork, beef, beans, tools, some furniture, household goods, old books, a few pieces of furniture, and a note with interest. He also had debts to Ephraim and Joel Oliver (grandson and son, respectively) and Edward Tuttle. Abijah and Joel signed a petition to sell the real estate to pay off the debts because a partial sale of the land would “greatly injure” the farm. Both sons stayed in Acton, however, and can be found in later years’ federal and state censuses and local records. We would like to find out more about John Oliver’s life, both in Acton and before he arrived. The 1790 warning out notice does not mention where he originally came from, but his pension application says that he was born in Concord in 1759. We have not been able to corroborate that in Concord’s records. (A search only yielded a John Oliver born to Peter and Margaret in 1747. That date better matches his age of 83 given in his 1832 pension record, the age of 92 in the 1840 census, his marriage in 1768, and a supposed 1772 birth year for son Abijah. However, it obviously conflicts with the 1759 birth year given in the pension application and his age of 23 in the 1780 descriptive soldier list.) John Oliver’s wife Abigail died in 1813. Evidently, she was Abigail Richardson who married to John Oliver on September 21, 1768 at the “Stone Chapel” in Boston. Abigail was the daughter of Ezra Richardson and Love (Parke). Her identity was confirmed in her mother’s probate record. Her mother’s will left all of her goods to a young grand-niece (apparently Love’s namesake). Included in the probate file is a March 13, 1793 agreement between the executor of the estate and “John Oliver of Acton... husband to Abigail Oliver”, splitting the goods between the named heir and “the said Abigail Oliver Daughter of said Love Richardson.” (Middlesex County Probate #19042) John and Abigail’s children’s births were not recorded in Acton at the time. (Only Abijah appears in Acton births, but in a later volume and without parents’ names. That information seems to have been added to Acton's vital records in the 1800s when Abijah's children's births were recorded as a group.) John Oliver’s death is mentioned in the town’s vital records without details, though his probate file is an excellent source of information about his family and possessions as of 1840. The house on his farm presumably did not survive; his homestead was not marked on an 1890 map of Acton’s old houses and sites created by Horace Tuttle (although John’s sons’ homes were marked). John Oliver’s grave evidently was marked with a Sons of the Revolution marker in 1895. Unfortunately, its location is no longer remembered; no gravestone exists. It is likely that he was buried in Forest Cemetery as was his son Joel and his daughter-in-law Esther, but that is conjecture. History can easily be forgotten unless someone makes an effort to preserve it. From the mid-nineteenth century on, Acton’s local historians and native sons and daughters wanted to emphasize Acton’s importance in the Revolutionary struggle by remembering its “first at the bridge” role. One can’t blame them when reading Lemuel Shattuck’s 1835 History of the Town of Concord (and Acton) in which he made the dismissive statements about the town of Acton that its history before the Revolution “contains no features worthy of particular notice” and afterwards “is of little general interest.” In reaction to such attitudes, more historical attention has been given to people who fought on April 19, 1775, and less notice has been given to others’ later war service. Acton provided many soldiers to the Revolutionary cause. Some of their identities, unfortunately, will never be known with certainty. Some, however, can be discovered. John Oliver’s service was extensive and his life in Acton long. He should be remembered. Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed