|

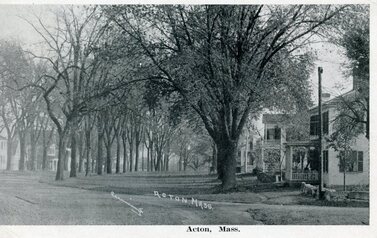

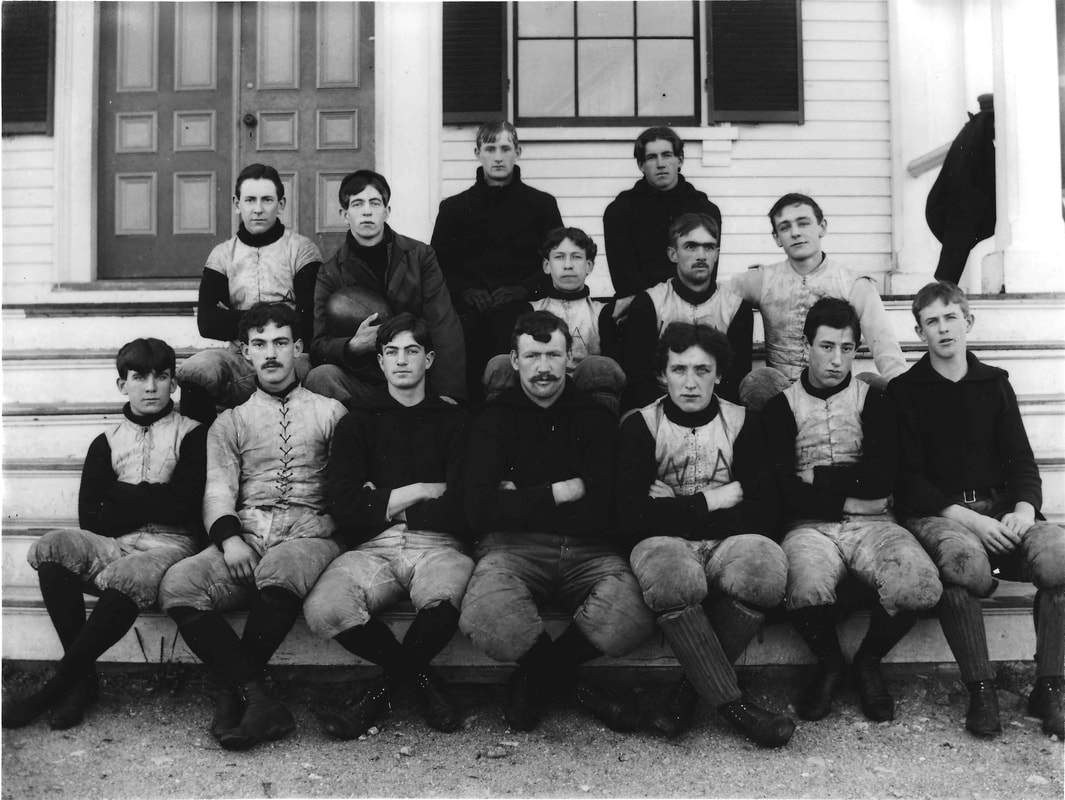

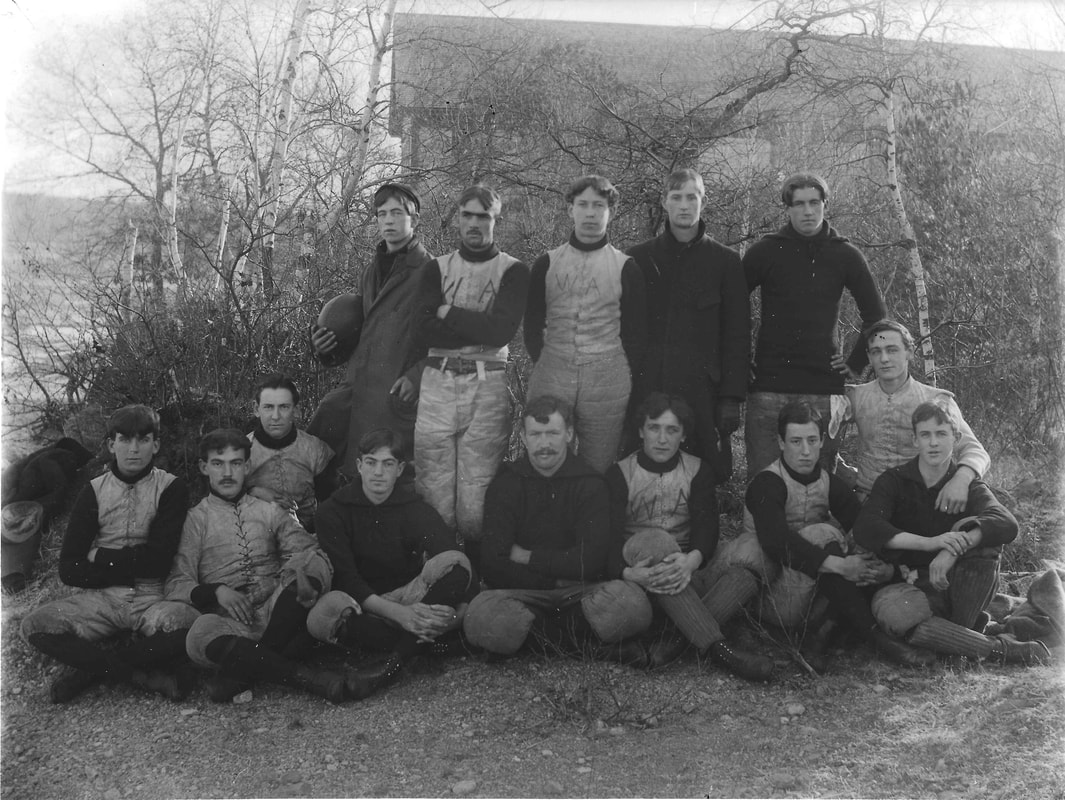

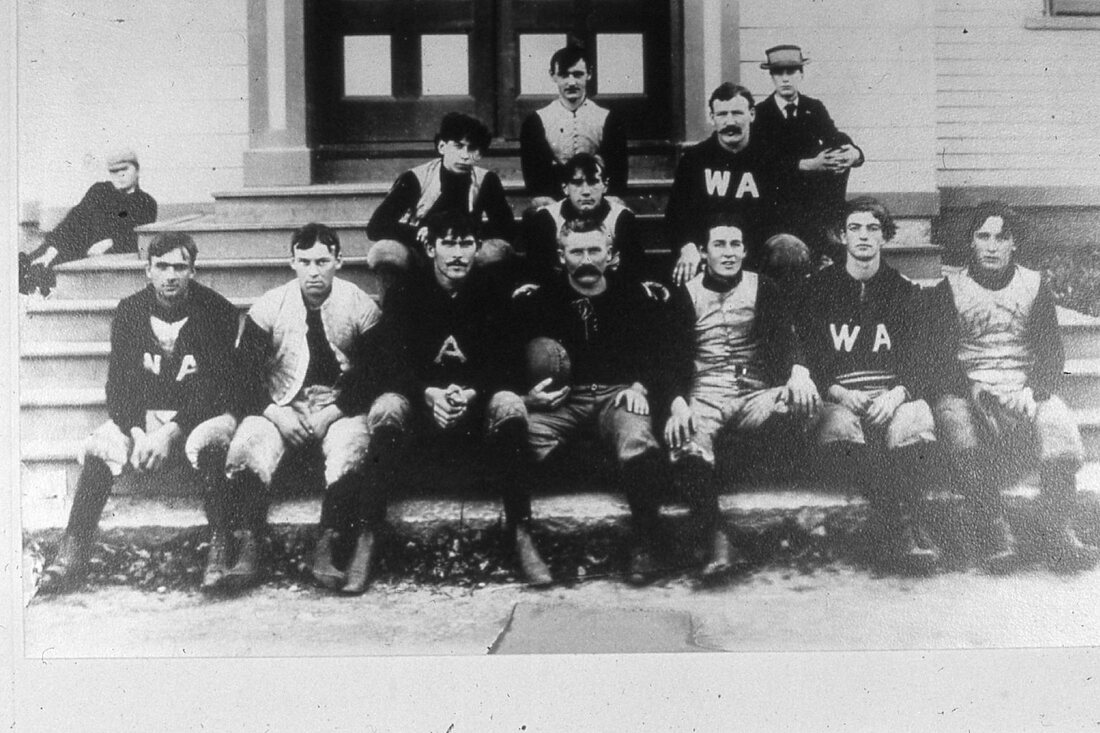

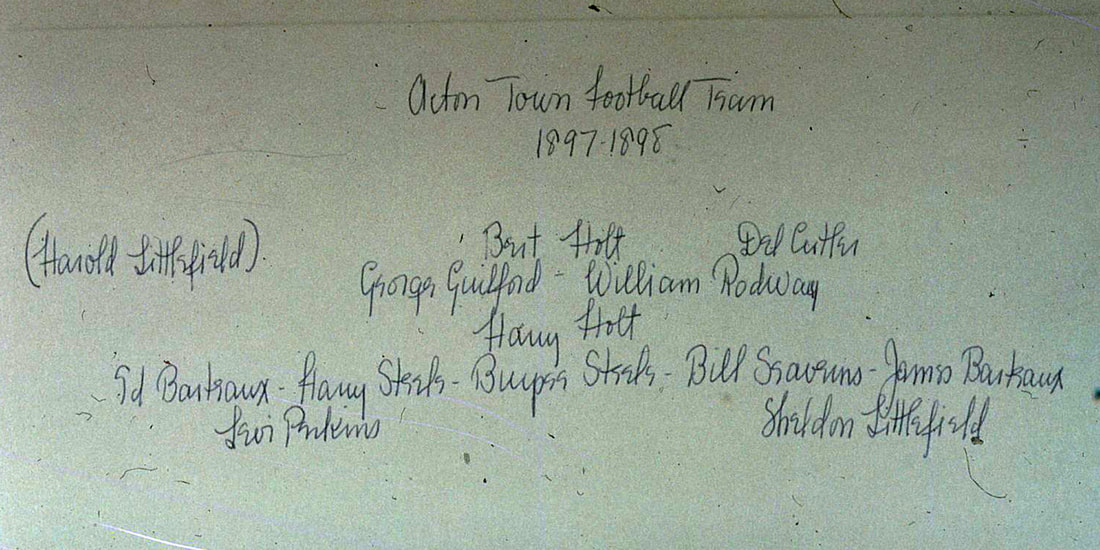

7/14/2021 Fun Times in the Summer 100 Years AgoA local newspaper article about South Acton a hundred years ago made us start thinking about what life was like for Acton residents that summer. The article mentioned that a new staircase and walk were being added to the west side of the old Post Office building, giving access to the newly-formed Young Men’s Athletic club rooms. “The walk in the rear will be six feet in width thereby [a]ffording the comforts of a piazza, where the members can sit, enjoy the beauties of nature in Theron park, watch the passing aeroplanes which of late has been of frequent occurrence, and wonder when the road sign is to be placed on the fountain.” (Concord Enterprise, August 31, 1921, p. 1) Curious about long how young athletes would be content to sit contemplating a road sign, we started investigating what people did for recreation in the summer of 1921. Reading the local newspaper, it would be easy to assume that summer vacations in 1921 were not so different from our own. The Enterprise reported on residents’ comings and goings as they had guests and visited friends and relatives. People vacationed at destinations similar to many visited by Acton residents today. They often headed to the beaches and mountains of New England, but some set out for places farther afield. Though not noted in the newspaper, much travel would have been done by train.  Hupmobile, c. 1921, Library of Congress Hupmobile, c. 1921, Library of Congress Automobiles were by now a more common part of life than they had been at the turn of the century, but residents’ car purchases were still reported in the paper. On August 31, for example, it was reported on the front page that Dr. Mayell was driving a Buick touring car, selectman Kingsley had a Ford, and Wesley Flagg and John Mekkelson had sport cars. Residents’ road trips by auto were highlighted in the paper all summer. It is easy to forget how different those trips would have been from our own experiences of the road, but occasionally an item in the newspaper reminds us of how driving has changed. The June 29 Enterprise reported on John Pederson’s trip to St. Albans in northern Vermont. (p.2, “Some Trip”) He drove continuously except to stop for meals, water, gas and oil. That sounds unexceptional, but it took him 23.5 hours to get there. The article did mention that Vermont’s roads were rough and mountainous in places. (The return trip in his truck loaded with furniture took even longer; hopefully he stopped somewhere for sleep.) John Pederson’s experience puts light on the ambition of Joseph Oliver who was reported in the August 10 paper to be leaving for California in his auto with his camping gear. (p. 1) It was probably helpful that he had previously been working in West Acton as an auto mechanic. By the early 1920s, autos were evolving. In 1915, Massachusetts had become the first state to mandate lights on automobiles, and federal standards for headlights were introduced in 1921. That summer, the local paper reported on the need for car owners to get their headlamps adjusted by authorized mechanics. (July 27, p. 7) Garages had sprung up in Acton and elsewhere to meet growing demand for service. John McNiff had closed up his blacksmith shop after 30 years of labor; he was reported to be contemplating opening a garage. (May 26, 1920, p. 7) There would have been competition. In the summer of 1921, ads ran in the Enterprise for the South Acton Garage, Fitzgerald’s Garage in West Acton, and the recently opened East Acton repair garage of Benjamin A. Kimball and Orville J. Fuller, the latter having already worked in automobile construction and repair for fifteen years. (June 29, p. 8) John Coughlin advertised that he would provide service “at your own garage”. (July 13, p. 4) Having a number of repair shops in town was quite useful. Despite improvements in automobiles, the downside of increased driving was dangerous interactions. The August 17 Enterprise reported on two serious accidents at Kelley’s corner the previous Saturday. (p. 1) In the late afternoon, a seven passenger touring car from Missouri struck broadside a Ford coming from Acton “with such force as to hurl it up against the building which stands at the northeast corner.” Fortunately, the occupants survived. Later Saturday evening as Mary McCarthy, Clara Binks, Bertha Gould and Frank Hayward were driving home from Lowell, they were struck by a “big car from Maryland.” Luckily, the damage was more serious to the cars than to the people. The paper called for improvement to the approaches to the busy intersection and for caution on the part of drivers. As one sits in traffic at that intersection of Main Street and Massachusetts Avenue, it is worth remembering to be grateful for stoplights. Finding Things to Do Despite the fact that roads had not yet caught up with the needs of automobiles, people in the summer of 1921 were on the go. Lawn parties were very popular, particularly as fundraisers. On the evening of July 21, the Acton Grange held its annual lawn party and dance. As announced on July 13, “The Maynard brass band will furnish a concert in the evening and the Highland Ladies’ orchestra of Somerville will play for the dance. There will be the usual attractions which make these lawn parties popular events of the summer.” (p. 5) The party was indeed a success. With convenient means of traveling, visitors came from Acton’s villages and elsewhere, including quite a few from Maynard. “It is said, that over two hundred automobiles were parked on the sides of Monument square.” (July 27, p. 4) Another popular diversion was “moving pictures,” regularly advertised in the Enterprise. There were often movies in the Concord State Armory to benefit the Red Cross and at a theater in Maynard, admission 25 cents for adults. Occasionally, a moving picture was shown in West Acton at Odd Fellows Hall. Acton residents also attended special out-of-town events. In June, several townspeople ventured to Lowell to see the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus that offered “the greatest congress of attractions in history” with hundreds of performers and a huge “wild beast” display. “Not only will you see the artists who occupy the three rings, five stages, the great hippodrome track and the aerial rigging in the tent top, but four spacious steel arenas filled with wild beasts as well.” (June 8, p. 7 and June 29, p. 2) In mid-August, various people from Acton attended the Pilgrim Pageant at Plymouth. The paper proclaimed that “Although pageants have been greatly in vogue for the last 10 years or more, this one entitled 'The Pilgrim Spirit’ and written by Prof. George P. Baker of Harvard university in commemoration of the 300th anniversary of the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth has been pronounced by an eminent professor of pageantry as the greatest performance since the pageants of the ancients.” (Aug. 24, p. 1)  Postcard of Acton Center sent July 1921 Postcard of Acton Center sent July 1921 Despite the reporting of some residents’ comings and goings in the newspaper, there were undoubtedly many Acton residents who found their amusement in town. The first challenge for them would have been to beat the heat. Shade was appreciated; Acton benefited from earlier residents’ foresight in lining streets with trees. Ads for electric fans at MacRae’s in Concord appeared in the Enterprise for those whose homes and businesses had been wired for electricity. (Getting electricity was also newsworthy in 1921.) Piazzas seem to have been quite popular. Presumably they offered the chance of catching whatever breeze there may have been and, for those on the more traveled thoroughfares, a chance to see the world go by. With summer came insects, of course, and the newspaper reported that Edward Conant, Harry Tuttle, George Dusseault and the West Acton Baptist parsonage were all adding screening to their piazzas. (July 13, 1921, p. 5; July 20, p. 4) Some of those out on their piazzas would have been able to watch the President’s cavalry escort from the Plymouth Pageant as they traveled to an overnight campsite in Maynard. Fifty-seven men came through with sixty-seven horses and eighteen mules. (Aug. 10, 1921 p. 1 and 5) While references to the military in the Enterprise were fewer than they had been in previous years, war’s aftermath occasionally was mentioned. In August, Charlotte Conant and Gertrude Daniels organized a clambake and corn roast at the Conant place for twenty ex-servicemen from the Groton hospital. It was followed by an informal dance in the afternoon at the town hall. (Aug. 24, p. 4) For those actively inclined, summer meant sports. The Acton villages had baseball teams, as in the past. The West Acton team was briefly dubbed the Pirates, but the name does not seem to have stuck. (Aug. 24, p. 8) The newly organized (or perhaps re-organized) Campfire Girls and the Young Men’s Club had a track meet reported June 15. Reverend R. J. May coached the young men, and Mrs. May led the Camp-Fire girls. The paper noted, “It will be unique in having both boys and girls as participants although not competing against each other.” (p. 5) In July, the groups were putting on plays at the Congregational Church. The young men were trying to pay for baseball equipment. The “Nashoba” Camp Fire Girls, meanwhile, “were completing their beaded head-bands and hope to earn their costumes by their entertainment.” (July 13, p. 6) Golf was taking off as an activity. During the summer of 1921, the Calvin Whitney farm in Maynard was being turned into the Maynard Country Club. By August, its charter members included a number of Acton residents, although applications from some who already had been on the waiting lists of the Framingham and Concord clubs were being held back to give Maynard residents priority. (Aug. 24, p. 1 and Aug. 31, 1921, p. 1) When it was time to cool off, a popular spot was a swimming hole on Martin Street (near present-day Jones Field) where there were often twenty people swimming at a time. (July 27, p. 4) Apparently, however, there were a few problems with the place as a recreation spot. On August 3, the paper reported: “CITIZENS IMPROVING BEACH – In response to the call for workers issued last week, a number of citizens met at the swimming pool at the Martin street bridge and proceeded to do what they could to improve the general appearance of the place, both in and out of the water. This spot has long been utilized as a dumping place for all kinds of rubbish, such as tin cans, bottles, lamp shades, bicycle frames in quantity and variety sufficient to stock an old curiosity shop and a generous amount was dragged out of the water and put where it can no longer be a menace to the bathers. ... This bathing place has been a source of much pleasure to many people this season, even though those who lived at some distance from the pool were obliged to return home wearing their wet bathing suits, under raincoats. With the place once put in good condition and a suitable bath house built there, it would be a great public benefit.” (p. 8) Summertime Wasn’t Always Drowsy There are always those who push the boundaries to create a little excitement. On July 6, the Acton Center reporter mentioned that “The Fourth was very quietly celebrated except for the ringing of the town hall and church bells from midnight to daybreak, which act of over-celebration should never be permitted in the future. Someone who stopped at the drinking fountain on the common as an act of rowdyism, broke the two water pipes.” (p. 7) Another item of interest for many would have been hearing amplification for the first time. The August 17 paper reported that the meeting of the Acton Agricultural association (attended by 150 members) was followed by a social hour, “one feature of which was the exhibition of a ‘magno box’ attachment to a victrola, by Robert W. Carter, a member of the association, the effect of which caused the music to be heard with wonderful distinctness in homes over a quarter of a mile away.” (p. 1) The paper did not mention what music Mr. Carter shared with Acton Center, but records advertised for 85 cents in the Enterprise that August were variations of the Fox Trot and songs with catchy titles such as “Anna in Indiana” and “Molly on a Trolley By Golly With You.” (Aug. 24, p. 8) A different kind of noisy excitement was reported from South Acton on Aug. 17. The milk train was coming toward Martin Street on the Boston and Maine tracks at about 8:40 on a Sunday morning. The engineer, as usual, blew the whistle in warning. However, the valve that controlled the whistle could not turn off the steam, so the train stopped at South Acton with the whistle “shrieking at a terrific rate.” The engine with the disabled valve was backed into a rear yard, still shrieking, and another engine took the milk train to Boston. “During the time of making the shift and for fifty minutes after the fire had been dumped from the engine, the whistle kept up a continuous shriek causing consternation throughout the town. Many persons rushed to the station supposing it to be an alarm of fire or that some serious accident had taken place.” (p. 7) The most exciting event of the summer, however, seems to have happened in Maynard. On the first page of the August 10 issue of the Enterprise was an article entitled “Knickers Invade Maynard – What Will the Women Spring on Us Next?” Apparently, a woman had the audacity to walk down Main Street dressed in “knickers, just plain pants they looked like, golf stockings, high brown tennis shoes, shirt waist, topped with a bit of rouge on the cheek and hair bobbed.” The result was commotion, men “pop eyed with astonishment,” and all of Main Street agog at the woman who was (supposedly) “as indifferent to the stare of the world as the sunburned one pieced bathing suit extremist. Business was suspended as clerks and staid proprietors made for a glimpse ... At first stunned, curiosity soon let loose a chatter and exchange of opinion as to the new styles.” In 1921, it was apparently a sight worth sitting on one’s piazza waiting for. 11/25/2020 Early Acton Football Revisited For those who are missing Thanksgiving high school football games in this strange 2020 holiday season, we offer some glimpses of football in Acton’s past. A favorite item in our collection is an 1890s leather football helmet. We are grateful to relatives of Ernest R. Teele who donated it. There are ventilation holes around the top, and it offered a bit of padding, but it was a long way from today’s headgear. Previously, we had written a blog post about the West Acton football team after seeing a team picture that only identified Ernest Teele (front row, second from left). In the time since, we have discovered other copies of that and a similar photograph of the team, both taken by Eugene Hall. (A number of his glass plate images were donated to our Society). However, we have not made any more progress on identifying the players. Some of our best discoveries at Jenks Library happen when we are searching for something completely different. We recently came across a reference to a 1960s slide copy of an old Acton football team photograph. Expecting that it would be a duplicate of the Eugene Hall pictures that we had already seen, we scanned the slide and discovered a different image. It had some familiar faces from our other pictures, but most importantly, names had been listed on the back. Trying to interpret the name list, we believe that the pictured men are as follows (corrections welcome!):

Among the players was William Rodway. This was a familiar name; as discussed in a blog post, he served in the Spanish American War a few months after this picture was taken. He made it back to a hospital in New York but died of disease there on October 18, 1898. He was known as “a young man of fine personal appearance and splendid physique” (Concord Enterprise, Oct. 27, 1898, page 8), so his succumbing to disease must have been a shock to his teammates and the community. For reasons that are unclear, when Acton’s monument to its Spanish American War veterans was put up, his name was left off of it. Now, at least, we have an identified picture of him. (As it turns out, he was front and center in the Hall pictures, as well, which jibes with our knowledge that he was team captain in 1896-7.) Another discovery that we have made since our original blog post on early football in Acton was that the West Acton team existed longer than we had thought. The 1900 team played Maynard High School on its baseball grounds on Thanksgiving. (Concord Enterprise, Nov. 29, 1900, p. 4) The following year, there was a Thanksgiving game between South Acton and West Acton football players. The rosters:

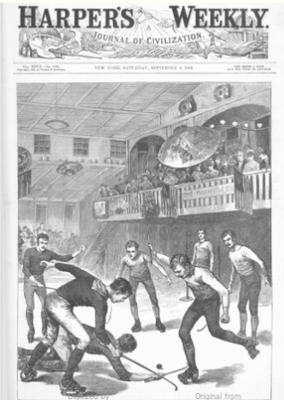

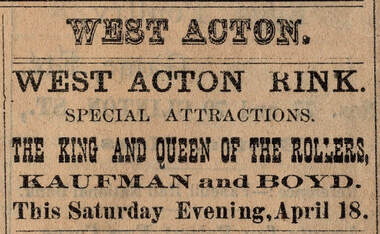

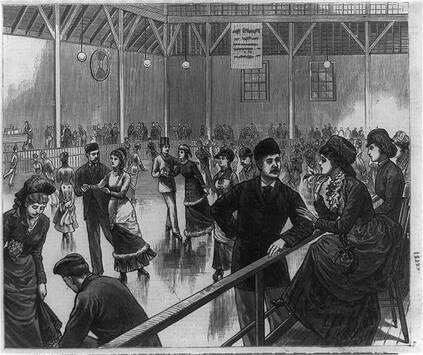

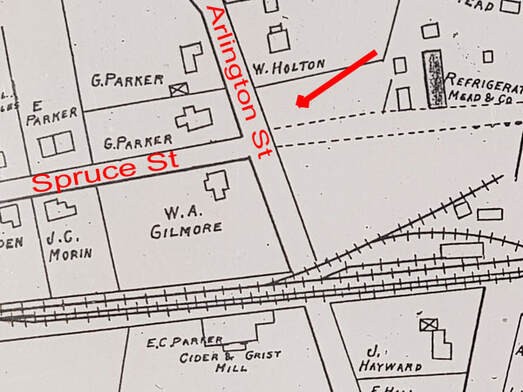

The Concord Enterprise’s South Acton correspondent described the game as “one-sided,” leaving the “West Acton linesman nothing to be thankful for,” while the “half-frozen spectators” looked on. The final score was 21-0. (Dec. 4, 1901, page 8) Here’s hoping that by next year, we will have the privilege, if we so choose, of braving Thanksgiving weather to attend our own favorite events. Cheering on friends and family in person sounds pretty good this year, cold or not. Some time ago, we came across a reference in an old newspaper to polo in Acton. Envisioning polo ponies charging through a local field, we filed that information away for another day. As it turns out, the team was actually playing a different game at a long-vanished West Acton business, a roller skating rink. In our archives, we found a description of the rink by Percy Wood. According to him, the West Acton rink was situated approximately at the southeast corner of today’s Spruce and Arlington Streets, a large rectangular building resting on posts several feet above the ground. Mr. Wood did not know the exact dates of or people involved with the rink, but he heard stories about it from Carrie (Gilmore) Durkee who lived diagonally across from it, at the site of the present-day West Acton Post Office. Because the rink was a short walk from the West Acton Depot, it was a popular spot for both out-of-town and local patrons. Conveniently, Carrie’s mother ran a boarding house and was able to provide meals and assistance to skaters, including helping female skaters into their heavy skating costumes. Wanting to verify and expand on Mr. Wood’s stories, we consulted standard Acton records. Neither the rink nor the Gilmore boarding house showed up in them. No nineteenth-century map in our collection shows a building at the rink’s location, and we did not find a mention of the rink in town reports, available directories, or tax valuations. Our access to the Concord Enterprise starts in 1888, but an online search of that paper yielded nothing. It happens, however, that our Society owns scattered issues of earlier newspapers, and luckily, the rink was mentioned in some of them, including an ad in the April 18, 1885 Middlesex Recorder [1, newspaper references at end]:  From The Champion Skate Book, 1884 From The Champion Skate Book, 1884 Clearly, the rink was operating in the mid-1880s, but we had to broaden our search to learn more. Acton’s rink was part of a much larger roller-skating phenomenon that swept the United States. Massachusetts native James L. Plimpton is credited with innovations that made roller skating a popular pastime. In 1863, he patented the quad-style roller skate (with two sets of wooden wheels that could be controlled by a skater’s shifting foot angle while all four wheels were still square on the ground, enabling easier turns and “fancy” moves than previous skates had). Plimpton then promoted the art of skating and started a franchise operation, leasing his skates to others. He also took his promotion, very successfully, to England and other countries. Over time, he improved on his own skate design, as did others; according to the Boston Globe, during the next two decades, over 300 roller skate improvement patents were filed, mostly in England and America. [2]. In Massachusetts, the Boston Globe announced in early 1876 that roller skating was gaining in popularity locally, emphasizing that participants included the “best elements of Boston society.” [3] Plimpton’s original patent ran out in 1880 and other innovations followed. Roller skating popularity exploded. Boston and Worcester had rinks, and as the craze spread, more and more local rinks were opened. The Fitchburg Sentinel reported that Clinton had a rink by 1880 and that Fitchburg’s rink would open in January 1882. [4] The Globe mentioned new rinks at South Framingham, Hudson, Leominster (two at the same time), and Ayer. [5] Unfortunately, we found nothing reported about building (or converting) a rink in West Acton or the exact date it opened for business. Photographs and illustrations of roller skating during its first phases of popularity are rare; the best we could find was this 1880 drawing of skating at a rink in Washington, DC, no doubt more fashionable than Acton’s. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)  Courtesy Hathi Trust / University of Michigan Courtesy Hathi Trust / University of Michigan Keeping a rink going meant getting patrons. Managers tried various strategies to attract crowds. They hired musicians to play during open skating hours, recruiting orchestras, bands, piano players, and even fife and drum corps. The big, open spaces could also host rallies and other large gatherings. The most commonly advertised special events at rinks were exhibitions by novelty acts, usually featuring talented, daring, unique, or very young skaters. In fact, the profit from performing apparently led some youngsters away from education, prompting New York state to pass regulations in 1885. [6] It was not long before competition was used to draw in skaters and spectators. Roller skating races were held, and large rinks could even hold bicycle races. [7] Games on roller skates were promoted, from “rink ball,” a game introduced in Brooklyn, New York and played with hands [8], to “polo on roller skates” played with a hard ball and sticks similar to those used in field hockey, but thinner. This polo played between stick-wielding skaters was new, and the game’s structure, equipment, and rules were still being worked out during the West Acton rink’s existence. Early play seems to have favored “rushing” with the ball toward the other team’s side. When a player rushed with the ball, the opposing team had time to line up in front of their “cage” and wait for the rusher to arrive. Passing, an innovation mentioned in a November 1885 Globe article, might catch the defense off guard. An attempt to make face-offs fairer had the referee throwing the ball against the side of the rink. [9] Other attempted innovations involved painting a stripe on the ball, using alternate materials for skate rollers such as cork, and installing netting to protect spectators. [10] Rival leagues had varying requirements. A Herald article described some of the rules set down by the New England Polo Association for its teams in October 1885. The game was to be played with six players on a side, competing for three goals out of five. There were referees who could impose fines for actions such as wearing extra padding, rough play, spitting on the floor, interfering in a dispute, tampering with skates or using profane language. (Fines went to the rink manager.) The referees could also expel players if necessary. [11] Rules seem to have been needed. The Globe reported that New Hampshire rink managers were disbanding their clubs for doing too much brawling. [12] Spectators occasionally were “disgraceful” as well. At one Waltham game, the crowd was calling out for bodily harm to be perpetrated not only on the opposing team but also on the referee. In addition, local fans were apparently helping out by punching an opposing player when he got to the corners of the rink. [13] Fortunately for our research, intense interest in roller skating and polo in the mid-1880s led Boston newspapers to report on action in outlying areas. From them we were able to learn something of what went on at the West Acton rink. The first mention that we found was the Boston Globe report on June 22, 1884 that Jessie Lafone (a teenager well-known for graceful and skillful skating) had performed an exhibition there the previous evening. [14] The first game of “polo on skates” played at the West Acton Rink was between the West Actons and the South Actons on August 16, 1884. West Acton’s “home team,” in their new uniforms, won the game with three straight goals in three minutes. (The object of the game was to reach three goals out of five.) Such a short show being bad for business, the proprietor asked the captains for a rematch. The second game was better contested, taking 15 minutes to end with a score of West Acton’s three goals to South Acton’s two. Player George E. Holton was singled out as an excellent rusher with “astonishing” accuracy in hitting the ball into the goal. [15] During the fall of 1884, the West Actons’ matches appeared in the news. The West Actons and South Actons met again on September 27. [16] Other matches reported in various papers were against the Websters of Boston, the Hudsons, the Leominsters, the Wekepekes (Clinton), the Alphas (South Framingham), and the Fairmounts (Marlborough). [17] The team joined the newly formed Union Polo League in November with Marlborough, Leominster, Clinton, South Framingham and Hudson. [18] The Globe mentioned the West Acton team having a game in the week of Dec. 21 1884. [19] Then without explanation, on Dec. 28, 1884, the Globe announced, “Owing to the disbanding of the West Actons and their withdrawal, the Hudsons lose two games, and the Wekepekes and Naticks lose one each.” [20] We have not found out the story of what happened to the West Acton team. Perhaps they were not performing well at that point, as the Globe had reported on the 16th that “The game at West Acton last Saturday evening, between the Wekepekes and West Actons, was won by the former in the remarkably short time of 2 minutes 5 seconds.” [21] The team also lost to the Naticks by allowing three straight goals on December 18th. [22] Perhaps West Acton had lost some players to other teams or to other pursuits. Competition between rinks was increasing; the Herald announced on December 14 that “Rinks are being opened at the rate of almost two a day.” [23] Close to home, Maynard’s new rink was about open. [24] Author Percy Wood did not know who owned or managed the rink, but our newspaper searches revealed that the manager was Thomas O’Brien. [25] He seems to have been quite enterprising. For example, West Acton’s innovative thinking was singled out in the Globe on Oct. 26, 1884 when the rink held a “Campaign race” in which all the presidential candidates were impersonated. To win, the impersonator had to reach the rink’s “presidential chair” first. The People’s Party was the winner. The Globe mentioned that “The Belva of the occasion was gorgeously gotten up,” a reference to suffragette Belva Ann Lockwood of the newly-formed Equal Rights Party. [26] Our own newspaper collection showed that Thomas O’Brien was busy finding ways to keep the rink excitement going in West Acton, even without a “home team” to cheer for. On February 27,1885, the Littleton Courant reported on a party on Feb. 14 at which all patrons received a valentine, an exhibition of the Milo Brothers’ “fancy skating and other feats,” and a “popular orange race,” (in which contestants would alternate grabbing an orange from a crate at the center of the rink and doing laps without dropping the oranges retrieved already). [27] A stained and torn Acton Patriot (April 24) in our collection tells us that J. F. Kaufman and Maud Boyd’s waltzing and fancy skating were “a marvel of grace and beauty, showing long and careful practice.” They called themselves “The King and Queen of the Rollers,” a title apparently claimed by many. The same Patriot reported that “Next Saturday at the rink there will be a gold medal race between E. E. Handley and George E. Holton. An interesting contest expected.” [28] Twice during 1885, the West Acton rink hosted games involving the Niagara female polo team, who seem to have been a good draw. [29] Thomas O’Brien had not given up on local polo teams at that point, because the April 24, 1885 Patriot also announced that “Rink Manager O’Brien has some gold medals he proposes to put up for competition between clubs formed in Acton, West Acton and South Acton and possibly Maynard. This is an interesting, exciting and scientific game. The medals will be of substantial style and worth playing for. Boys, get your sticks and uniforms ready.” [30] Sadly, we have no more local papers of the period to tell us what happened. When the Union Polo League planned their organizational meeting for the fall season on October 19, the West Acton rink manager was included. The Herald reported that the South Actons would be one of the teams, but when the League’s membership was announced the next week, it only included clubs from Arlington, South Framingham, Clinton, Hudson, Marlboro and Maynard. [31] We were not able to find any mention of a South Acton team’s games. The rink had other problems besides lack of local polo teams. Harmless as roller skating seems to us today, the pastime encountered strong objections from some members of the clergy including the minister of West Acton’s Baptist church Rev. C. L. Rhodes. According to Percy Wood, Rev. Rhodes “strongly warned the young people of [his] church to stay away from what he evidently regarded as a den of iniquity.” Presumably, some of his flock listened to his warnings and did indeed stay away. Others seem to have ignored him. One young man who later became a pillar of the community obeyed his preacher by avoiding the West Acton rink and skating elsewhere instead. Rev. Rhodes was not alone in his condemnation. The Lowell Sun reported that “The game of polo originated in the modern den of depravity known as the skating rink, and it has proved itself worthy of its low and demoralizing source.” [32] Morality was not the only concern. The Globe quoted a doctor, who, in trying to understand the cause of a large increase in pneumonia deaths, blamed roller skating. Acknowledging that he was just speculating and that people died of pneumonia without roller skating, he went on to say, “But I can say with certainty that such exposure as the roller skating mania produces is likely to produce pneumonia. Here are, say 20,000 young people going every night to skating rinks or balls. They indulge in violent exercise in heated rooms and then go out into the chill air, possibly thinly clad, and the result is fatal inflammation of the lungs.” A young woman who danced vigorously and then went outside in her ballgown would be considered “very indiscreet,” yet skaters, finding the cool air pleasant, apparently made a habit of walking “through the chilly streets while yet perspiring from their violent exercise.” [33] It is hard to say what effect such opinions had on the West Acton rink. Though it survived 1885, we have found no mention of it after that. The roller skating craze had probably peaked by then, and increased competition undoubtedly caused a shakeout in the market. Ads started appearing for rink sales. In July, 1885, an ad for a rink mentioned “good reasons for selling.” [34] In November 1885, a “first-class skating rink” an hour from Boston was looking for an infusion of capital, and in December the Globe advertised a skating rink with fixtures “in large town for 1/3 value; good chance to make money; no competition.” [35] Even more dramatically, the Globe reported that a skating rink built for $17,000 the previous year with a white marble “underpinning,” and $4,000 of skates had been offered for sale at $800. [36] After the West Acton rink closed, it evidently stood empty. Percy Wood reported that the rink building “had one narrow escape from destruction from fire on a Fourth of July during which many of the citizens were out of town. A fire broke out in the storage shed located between the railroad tracks and the present Spruce Street. Fortunately, the fire was confined to the area in which it started, despite the lack of manpower and only the most primitive fighting equipment. The rink was, however, seriously threatened and was saved largely by the efforts of a man who was nearly exhausted by his exertions but was revived by a bowl of ginger tea supplied by a kindly neighbor.” Newspaper searches, unfortunately, did not turn up information about that fire, so we were unable to confirm the date. Percy Wood continued, “Instead of being left to stand as an eyesore, the building was taken down by Mr. John Hoar, the well known contractor and builder, and was used to construct a house on Central Street in West Concord. But on the original site Arlington St. in West Acton, there is not a trace of what was once a popular amusement center.” Whenever the West Acton rink disappeared, we know that sport and exercise in Acton continued. The Concord Enterprise reported that the Acton Cycle Club polo team went to Concord and defeated the home team’s “gentlemanly fellows” in February 1895. [37] That game may have been played on ice, as “ice polo” teams were forming in the 1890s. Toward the end of that decade, West Acton had another chance at indoor roller skating. The ever-enterprising Hanson A. Littlefield announced in the January 6, 1898 Concord Enterprise that Littlefield’s Hall had been fitted for roller skating. Open skating would cost ten cents, and the facility could be rented by private parties. [38] We do not know how long that lasted, but the Hall itself burned down in 1904. The West Acton roller skating rink might have completely escaped our notice if it had not been for Percy Wood’s documenting Acton memories. Thanks are also due to organizations that are digitizing and sharing old newspapers. If anyone has pictures or mementos of West Acton’s roller skating rink or Acton’s polo teams that they would be willing to share, donate or scan, we would be very grateful to add them to our archives. Sources Newspaper References: [1] Middlesex Recorder, Apr. 18, 1885, page 3 (Jenks Library) [2] Boston Globe, March 23, 1885, p.4 [3] Boston Globe, Jan. 27, 1876, p. 5 [4] Fitchburg Sentinel, April 7, 1880, p. 3; Dec. 16, 1881, p. 3 [5] Boston Globe, Nov. 18, 1883, p. 6; Jan. 20, 1884, p. 2; March 23, 1884, p. 6 [6] Boston Globe, Apr. 16, 1885, p. 8 [7] Boston Globe, Nov. 27, 1885, p3; Mar. 24, 1887, p. 5 [8] Boston Globe, Jan. 14, 1878, p. 2 [9] Boston Globe, Nov. 19, 1885, p. 3 [10] Boston Globe, Jan. 20, 1884, p. 2; Mar. 23, 1884, p. 6 [11] Boston Herald, October 14, 1885, p. 2 [12] Boston Globe, Jan. 31, 1885, p. 4 [13] Boston Herald, Nov. 25, 1885, p. 3 [14] Boston Globe, June 22, 1884, p. 6 [15] Boston Herald, Aug. 17, 1884, p. 2; Boston Journal, August 19, 1884, p. 3 [16] Boston Journal, Sept. 30, 1884, p. 4 [17] Boston Herald, Aug. 31, 1884, p. 2; Boston Globe, Oct. 24, 1884, p. 2; Boston Herald, Dec. 7, 1884, p. 7; Worcester Daily Spy, Dec. 8, 1884, p. 3; Boston Herald, Dec. 14, 1884, p.4; Boston Globe, Dec. 19, 1884, p. 2 Boston Globe, Dec. 21, 1884, p. 10 [18] Boston Journal, Nov. 24, 1884, p. 3; Boston Globe, Nov. 23, 1884, p. 15 [19] Boston Globe, Dec. 21, 1884, p. 10 [20] Boston Globe, Dec. 28, 1884, p. 10 [21] Boston Globe, Dec. 16, 1884, p. 6 [22] Boston Globe, Dec. 19, 1884, p. 2 [23] Boston Herald, Dec. 14, 1884, p. 4 [24] Boston Globe, Dec. 21, 1884, p. 10 [25] Boston Globe, Nov. 23, 1884, p. 15; Nov. 30, 1884, p. 10 [26] Boston Globe Oct. 26, 1884, p. 14 [27] Littleton Courant, Feb. 27, 1885, p. 1 (Jenks Library) [28] Acton Patriot, April 24, 1885, p. 4 (Jenks Library) [29] Boston Globe May 24, 1885, p. 6; Boston Herald, Oct. 11, 1885, p. 15 [20] Acton Patriot, April 24, 1885, p. 4 (Jenks Library) [31] Boston Herald, Oct. 18, 1885, p. 7; Boston Globe, Oct. 24, 1885, p. 2 [32] Lowell Sun, March 28, 1885, p. 4 [33] Boston Globe, Mar. 19, 1885, p. 6 [34] Boston Globe Jul. 20, 1885, p. 3 [35] Boston Globe, Nov. 17, 1885, p. 7; Dec. 30, 1885, p. 7 [36] Boston Globe Sept. 25, 1885, p. 6 [37] Concord Enterprise, Feb. 7, 1895, p. 4 [38] Concord Enterprise, Jan. 6, 1898, p. 8 Other Sources: Though these references do not mention Acton, they give great detail about the history and state of roller skating and roller polo at the height of the 1880s boom:

8/6/2019 Yachting in Acton Camping at Lake Nagog, Aug. 1890 Camping at Lake Nagog, Aug. 1890 Researching Acton’s July 4th celebrations, we discovered the surprising fact that Acton once had a yacht club. It is hard for us to imagine, for yacht clubs bring to mind ocean sailing and large vessels owned by wealthy individuals such as Acton descendant Francis Skinner. However, at the turn of the twentieth century, local enthusiasts brought their sailing excitement to Acton. By the late 1800s, Lake Nagog had become a destination for summer recreation. Though Acton residents traveled to the ocean and the mountains for vacations, they also spent time at camps on the shores of their local pond. It is not surprising that they would want to spend time on the water, and races would have provided entertainment for their friends and relatives. The West Acton Yacht Club first shows up in the local paper on August 17, 1899 as the sponsor of a race between the yachts of brothers Frank and Octavus Knowlton, the Evadne and the Wawanda, respectively. (Concord Enterprise, Aug. 17, p. 8) According to the Sept. 14 Enterprise (p. 8), the West Acton Yacht Club was officially organized on August 24, with officers Delette H. Hall (Commodore), Charles J. Holton (Vice-Commodore), and E. C. Stevens (Treasurer and Secretary). On the Regatta Committee were Frank R. Knowlton, Frank A. Patch, and Edgar H. Hall. The Enterprise helpfully listed the other members of the club, many of whom were West Acton businessmen: D. Adelbert Cutler, Sidney Durkee, Fred W. Green, James A. Grimes, Henry L. Haynes, Octavus A. and Roscoe Knowlton, Hanson A. Littlefield, Charles H. Mead, Richard Nichols, E. Wellington Rich, J. Linwood Richardson, Frank H. Stevens, and Arthur, Frank H. and Waldo E. Whitcomb. The yacht club’s first big event seems to have been a race between three boats, Evadne, Alice and Madcap. The prize was a silk pennant (and bragging rights), won by the Frank R. Knowlton’s Evadne. After the race, a clambake was held “on the grounds of F. R. Knowlton and Hall Bros.” The menu consisted of “baked clams, baked stuffed cod, green corn, sweet and Irish potatoes, melons, coffee, lemonade, bread and cake; a bountiful spread, cooked and served a la sea shore.” (Enterprise, Sept. 14, 1899, p. 8) The Society owns a print of a collage made from a series of glass plate photographs taken by Eugene L. Hall. It includes scenes from Lake Nagog, including “Know-Hall Grove” where the clambake must have been held. A boat was moored nearby. There are a couple of pictures of boats with sails up, but they were tucked under other images in the collage. Only a partial picture of the Madcap survives, and the other boat picture was only labelled “Wharf Lake Nagog.” Because the images are very small and come from a photograph of printed photographs, their quality is not ideal. If anyone has prints of the full images (or the original glass plates), we would be very grateful for copies or scans. The summer of 1900 saw a series of Acton yacht races. More boats participated; one race reportedly had six entrants, O. A. Knowlton’s, F. R. Knowlton’s, D. H. Hall's, E. C. Stevens’, Jas. Grimes’ and S. T. Blood’s (Enterprise, Aug. 16, 1900, p.8 ) However, sailing on Lake Nagog seems not to have been as simple as one might expect. The July 4th race saw various mishaps, and only the Hall boat reached the finish line. (Enterprise, July 12, 1900 p. 8) In September, a good race was held in which the two Knowltons’ boats and others survived, but the Hall brothers’ boat had to withdraw, completely disabled. (Enterprise, Sept. 6, 1900 p. 8) In the only 1901 mention of local yachting that we could find, on September 4, the Enterprise reported “The yacht race at Nagog Monday was not a success, the wind not being favorable. But the dinner was all that could be desired. Steamed clams, corn and all the accessories ... About one hundred enjoyed this feature.” (p. 8)

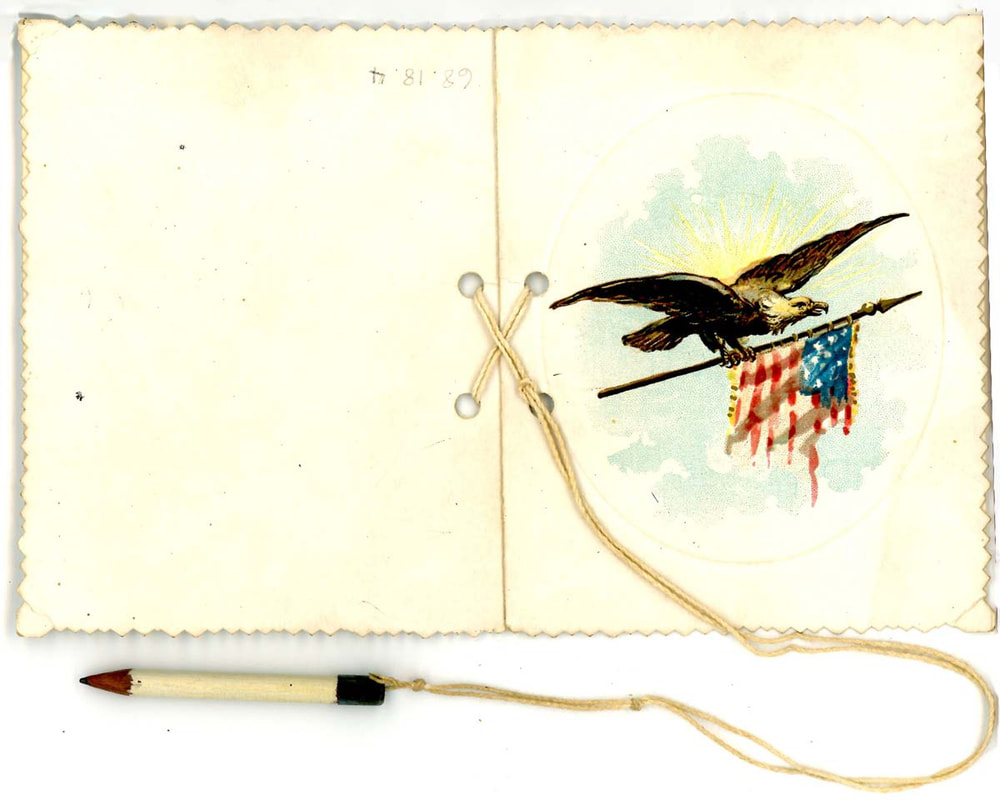

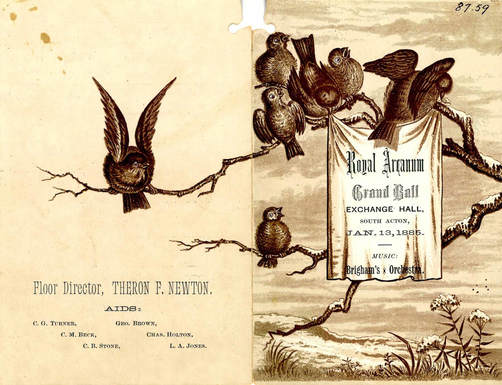

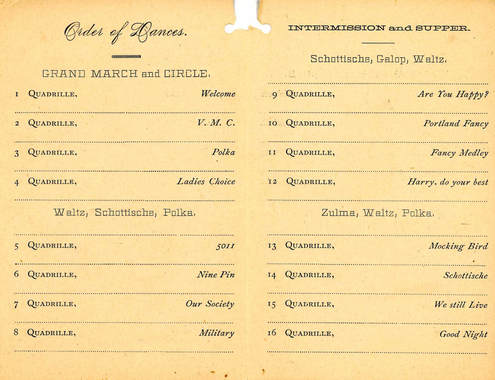

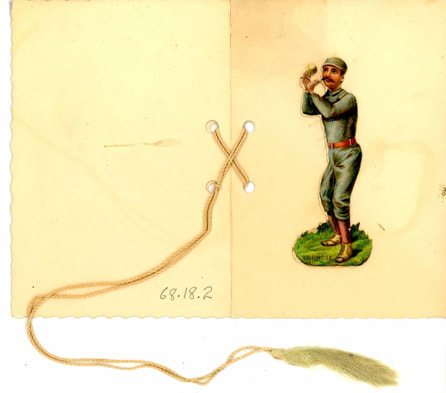

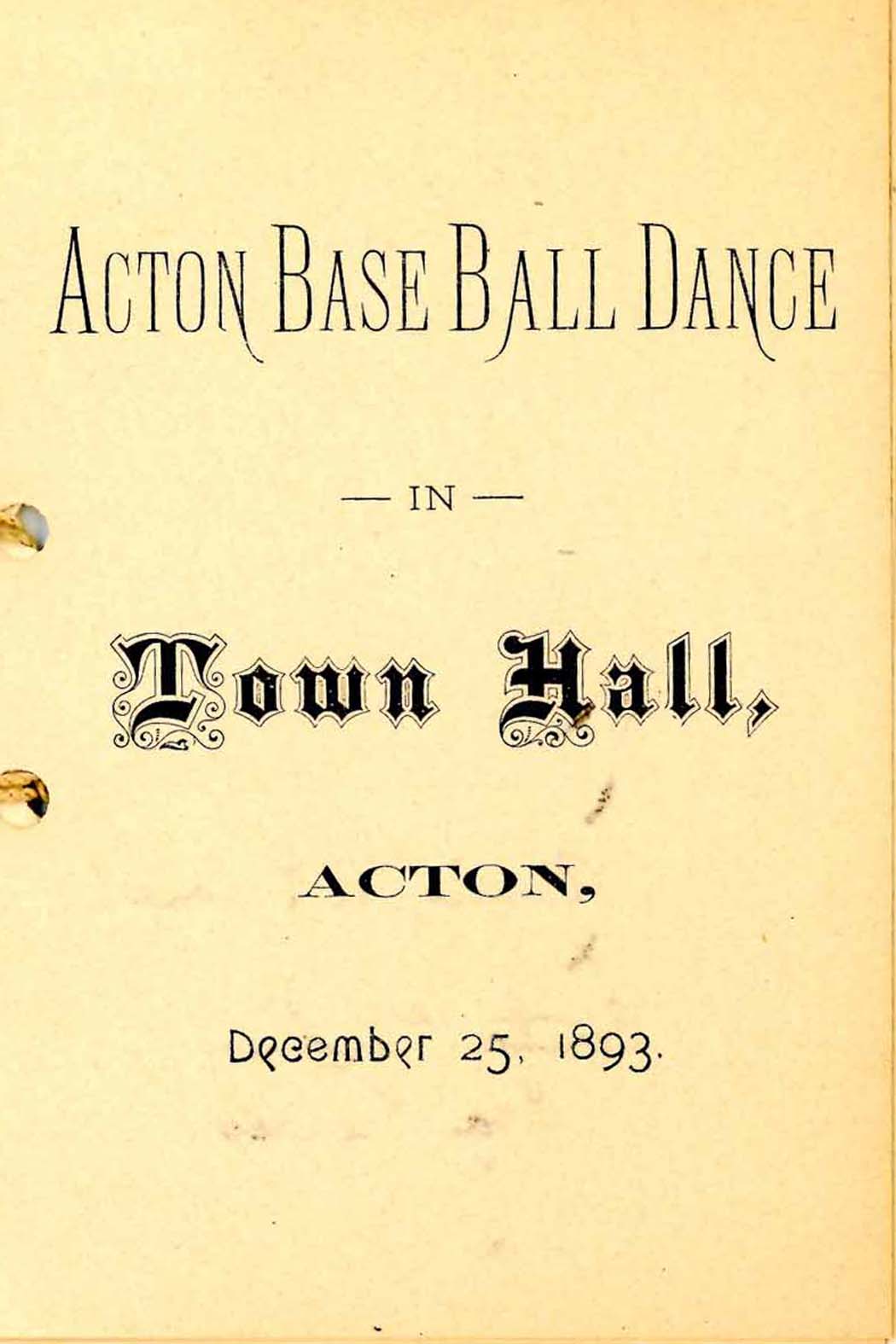

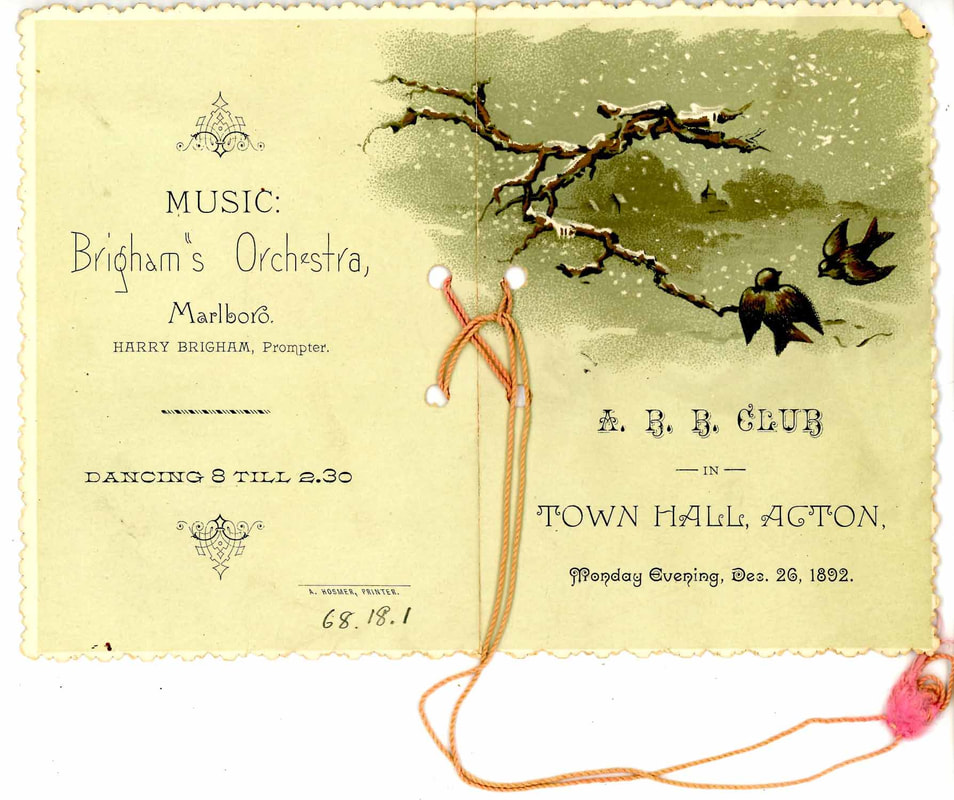

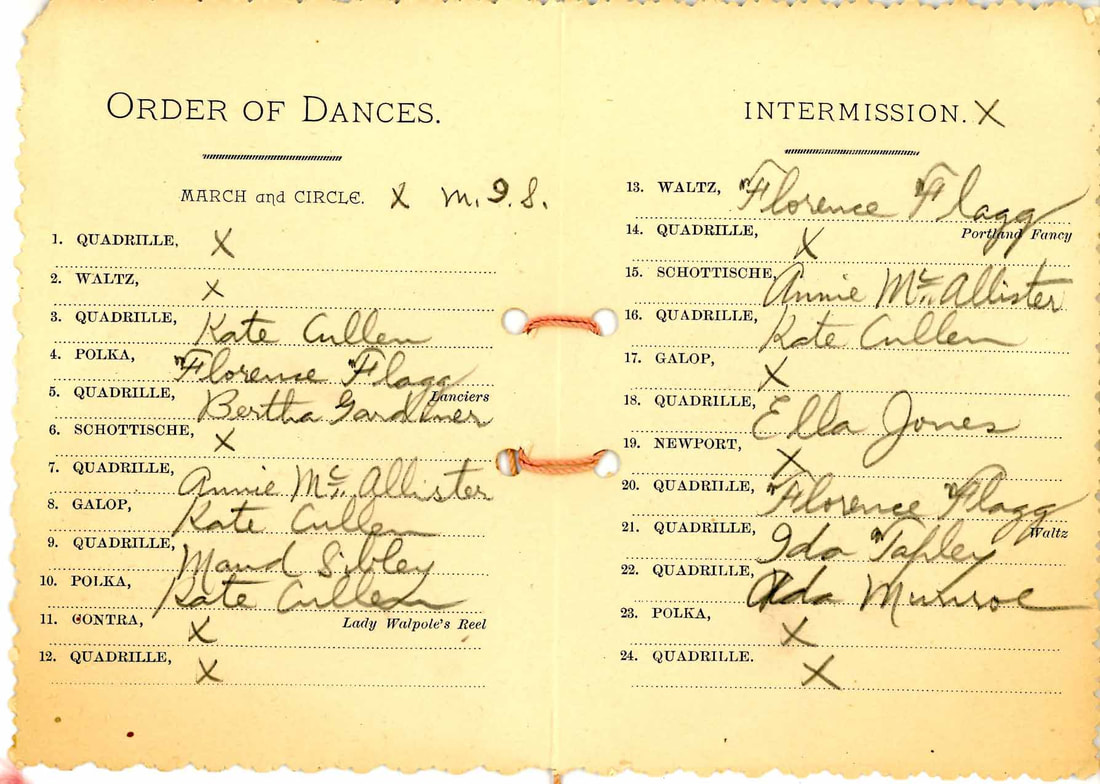

We found no reports of the West Acton Yacht Club after 1901. Perhaps the dispiriting winds of that Labor Day race cooled enthusiasm for the venture. Sailors presumably found other sites for their boats. A few years later, Nagog water would be piped to Concord, and recreational use of the pond would eventually cease. 12/1/2018 Dancing the Night Away in ActonThe Society is lucky to have a collection of dance cards that were obviously kept as mementos. They give us a glimpse of Acton's community life in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Despite the fact that people lacked today's conveniences, they clearly were able to enjoy social occasions. As far back as we have newspaper records, we find that dances were held in town. Venues included the Town Hall in Acton “Centre,” Exchange Hall in South Acton (both built in the 1860s), and Littlefield’s Hall in West Acton (built about 1893 and burned down in 1904; see our blog post for further information). Our earliest dance card was created for the "Eighth Annual Bal Masque" held at Exchange Hall on January 21, 1875, confirming that dances were being held as far back as the 1860s. Holidays were favorite occasions for formal balls, but dances seem to have been held quite often. Some were fundraisers for local groups, some were either public or private celebrations, and others may have been private profit-making ventures. Dance cards were printed in advance with the details of the event, usually including the committee in charge and the group who would provide the music. The inside of the card listed the dances that would be performed. Blank lines were provided for filling in the name of the partner to whom each dance was promised. The card would have a decorative cover, making it an attractive souvenir of the evening. Held together by a string or ribbon, the card sometimes had a pencil attached for convenience. One of our earliest dance cards was created for the Royal Arcanum Grand Ball held in Exchange Hall on January 13, 1885. The dances and musical selections were specified, mostly quadrilles, (danced in squares of four couples), with a few partner dances interspersed. In the middle of the Ball, there was an intermission and a supper. According to newspaper reports, the local baseball club held fundraising dances as far back as 1884. Several of our dance cards made it very clear that patrons were supporting the team. Researching the use of dance cards, we found that many sources indicate that dance cards were filled in only by men seeking to reserve dance partners. Our collection shows that women sometimes filled in dance cards, too. In keeping with the customs of the time, the owner of this 1892 card danced with more than one partner, but the with “M.I.S.” was carefully blocked out, including the Grand March and the first and final dances. We also note that a wide variety of dances were offered, with a mix of group dances such as the Quadrille and the Contra and partner dances such as the Waltz, Polka, Schottische, Galop and the relatively uncommon Newport.

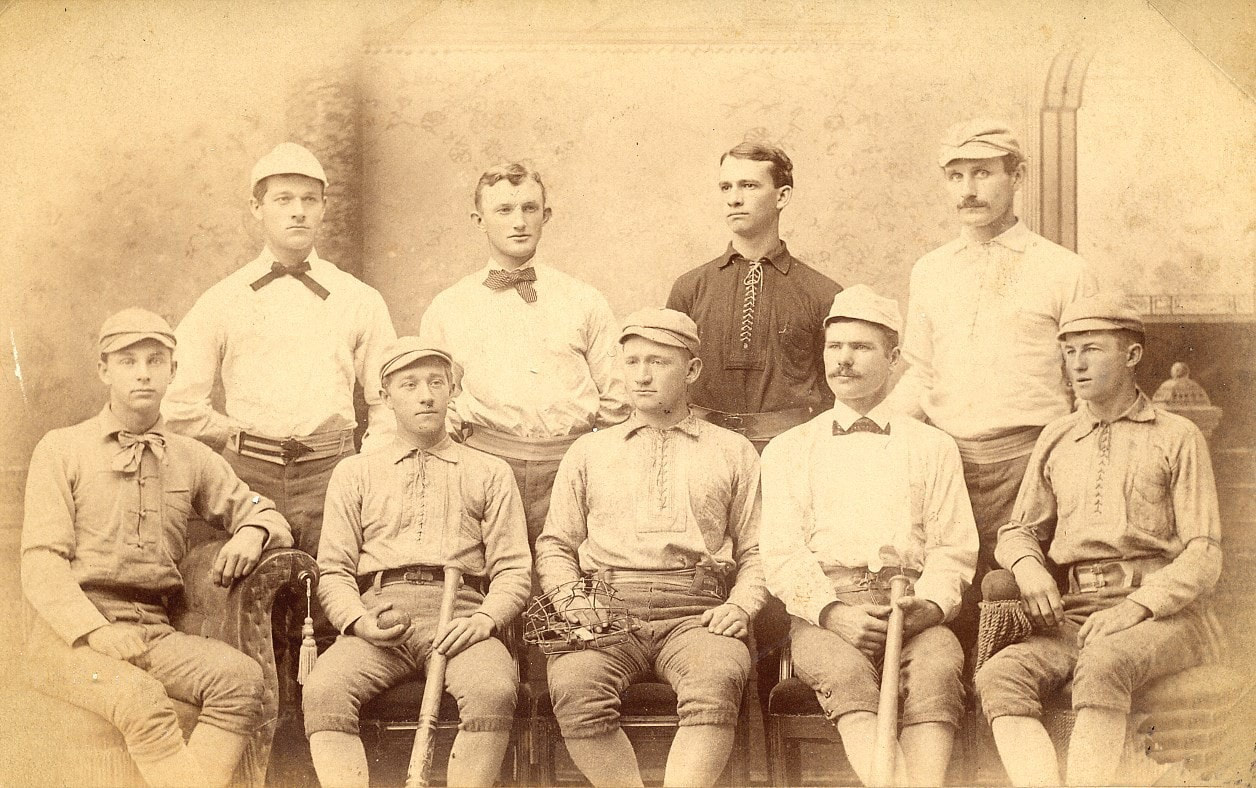

Attendees were not all dancers. According to newspaper reports, spectators could buy tickets for the platform or the gallery. The Society has an invitation to a 1904 South Acton dance which cost $1 for a “subscription” and only 25 cents for an orchestra or balcony chair. In the Town Hall, in 1896, non-dancers at the Christmas dance were given an adjoining room at which to play whist (Concord Enterprise, Dec. 24, page 8). The events, at least for the more formal occasions, would include a meal. An advertisement in the November 23, 1899 Concord Enterprise (page 8) told dancers what they could expect at the Thanksgiving Ball at Littlefield’s Hall; a “hostler” to take care of horses at the door of the Hall, a coat check and convenient toilet rooms, an excellent dance floor, good music, and a supper for 35 cents consisting of various oyster dishes, pickles, olives, ice creams, cakes, fruit, and coffee. The ad made the claim that “No where in this vicinity is offered so many advantages for comfort and facilities for enjoyment at a ball, as at West Acton.” The competition for dancers evidently was becoming fierce. Organizers of a Concord Junction dance advertised in the South Acton and West Acton locals on November 16. South Acton’s Thanksgiving Ball organizers offered anyone who bought Ball tickets free admission to a dance the week before. A report on the complimentary dance mentioned that “best of all there was no dust in the hall." (Nov. 30, 1899, page 8). The December 7 issue of the Enterprise (page 8) reported that the South Acton Thanksgiving Ball was “great success” with 80 couples who had “tripped the light fantastic toe” and every spectator seat filled. In contrast, the West Acton news included a letter from H. A. Littlefield denouncing “as false the malicious story started Thanksgiving day or the day before that my family was sick with diphtheria and that I was not allowed to be out” so that “it would be imprudent to attend the ball in Littlefield’s hall. The story had its effect; there was no time to refute it and it spread with a rapidity that leads to the conclusion that it was pre-arranged.” Stories, true or not, spread quickly in a small town. One other item of note struck us as we looked at the old dance cards; the affairs could be long. Starting around 8 pm and including a dinner, they went as late as 2:30 am. Getting home, for those who lived beyond easy walking distance, would have involved using and then caring for horses after a long night. One has to be a bit awed by former Actonians’ energy. 9/22/2018 A Baseball Team to IdentifyA reader of our blog post on Acton's early baseball kindly sent us a studio picture of another local baseball team. One of the players is identified; the man seated at the far right is Jim O’Neil, born in Acton in 1878. The picture was estimated to have been taken sometime around 1898. It is possible that the photograph may have been an East Acton baseball team. We found a July, 1897 article that listed the team at that time:

M. Hayes, catcher F. O’Neil, pitcher S. D. Taylor, shortstop H. Holt, 2nd base S. Guilford, Left field C. Smith, 1st base J. O’Neal, centerfield F. Davis, right field T. Hayes, 3rd base Players moved around, so it is also possible that Jim O'Neil played for another team. Trying to research the 1897 East Acton team's players, we found players M. Hayes and T. Hayes on a Concord Junction team in 1902. Can anyone help us to identify this team or any of its players? Please contact us. 7/16/2018 Acton Baseball's Early Days The Society has in its collection a picture of an Acton baseball team. Unlabeled, its only clues are the team uniforms, most of which say Acton, and a sweater with a date that indicates that the picture was taken in the first decade of the twentieth century. Trying to find out more about the history of Acton baseball in the Society’s archives, we were surprised to find that our collections do not have a lot of detail about the sport or early players in town. Perhaps baseball was so commonplace that most people did not think to record its history or to save souvenirs. There is disagreement about when “base ball” actually started, but we know that the game goes back to 1840 or before. The earliest mention that we found of the sport in Acton was a comment in the School Committee report of 1861-1862 that in the school yard, the “bat and ball and every other boyish play” had been replaced by military exercises deemed better physical training in the Civil War years. (page 11) We do not know exactly when adult teams were organized in Acton. Newspapers covering Acton news before the late 1880s are hard to locate. The earliest local team that we could find was mentioned in the Boston Journal, August 23, 1875 (page 4), playing the Edens of Charlestown. The Boston Daily Globe (Jan. 15 1917, page 15) reported that a reunion was being planned of the New England players of 1873-1875 who played against the Bartlett Club of Lowell. Among them were the Actons. We also found an entertaining report on West Acton’s 11-inning outing against Fitchburg in 1876. The article detailed the exploits and occasional errors of Acton’s players Campbell, Conant, Driscoll, Gardner, Marshall, Mead, Taylor, A. Tuttle and J. Tuttle. (Fitchburg Sentinel, July 31, 1876, page 3) Phalen’s 1954 History of the town of Acton mentions “Mr. Hoar’s” recollection of “Acton’s first knights of the diamond,” which probably overlaps with the Fitchburg game list, (though he dated the first team at 1877): James B. Tuttle, Frank Marshall, George Reed, Edward F. Conant, Charles Day, Arthur Tuttle, Simon Taylor, John Hoar, William Puffer, Lyman Taylor, and Dennis Sullivan. (page 225) One would assume that in the earliest days, local teams were organized with local players. A manager handled arranging games and finances; he would have had to find equipment and (eventually) uniforms for the team, locations at which to play, and a way to travel to games. By the time we find Acton teams in local newspapers, team composition was not necessarily all native. Small towns might not have had adequate “talent” to cover all positions. In May of 1888, the Concord Enterprise reported that the Acton team had procured a baseman named Baker who previously had been captain of the Marlboro team; “He is just the man Actons want, and we are glad the managers were able to secure his services for the coming season.” (May 12, page 2) In turn, Acton’s previous second baseman transferred to the Nashua team. Concord apparently managed to field its own team that year. A very pleased reporter from Concord reported on a June 1888 victory over Acton. Piling on insults, he turned around the often-repeated assertion that it was Acton men who had done the fighting at Concord in April 1775 and then made sure to mention that Concord’s baseball team was made up of Concord residents: “They came, they saw, but alas! They were conquered..... How true it is that history oft repeats itself. It is only a little over one hundred and thirteen years ago that Concord furnished the field for Acton corpses, and Saturday afternoon she repeated the operation... There seems to be some doubt, however, as to the entire remains belonging to the town of Acton, it having been whispered that certain other towns contributed their quota to aid Acton in its endeavor. If this rumor be true, then all the more glory for the boys of old Concord.” (Enterprise, June 30, 1888, page 3) The author also had opinions on the behavior of some of the 200 people at the game: “A large delegation from Maynard, Acton and Westvale came down to see the fun and cheer the Actons to victory. They were anxious to bet, even as high as 2 to 1 on their favorite nine, but fortunately for them they struck a town where such a use of money is not countenanced.” The author made some suggestions to the public, urging them to support the team and “above all things don’t guy [ridicule], or give advice to the players; it is neither witty or wise, and is very annoying to both the public and the players.” Despite the Concord reporter’s gloating over the victory of a purely “Concord” team, it was clear from news reports that teams paid to get good players, either for a season or on a temporary basis to fill holes in the roster. On May 31, 1889, the Concord Enterprise explicitly reported that the West Acton club would need to pass the hat around “owing to the large salaries paid to new players.” (page 2) The Boxboro base ball club in 1892 “intent upon defeating their ever victorious rivals... procured, at considerable expense” players from Boston to help them defeat the strong West Acton team. The result was a classic game of neighborly rivalry. Boxboro led 6-0 after eight innings, to the elation of “the large delegation among the spectators of Boxboro farmers who had left the hay field and taken their families to the game...” Unfortunately for the Boxboro crowd, in the ninth inning, West Acton managed to score three runs. With two outs, Conant, a noted member of the “old Actons,” hit a grand slam into the woods, clinching the game for West Acton. (Enterprise, July 29, 1892, page 4) One can only imagine the reaction from fans on both sides of the contest. Venues varied. In the early days, the town did not provide athletic fields; teams had to find owners of land who would allow them to play. (We did not find any mention of rental fees paid until much later, so we do not know whether it was a business decision or pure generosity on the part of the owners.) The August 18, 1888 Enterprise (page 2) mentioned that “The Actons can boast of one of the finest ball grounds in the state, and all through the kindness of Mr. Barker who gives them the use of the ground and also keeps it in first-class shape. But it must be distinctly understood that his apples are not free, and the acts of last Saturday must not be repeated.” Presumably, the generous field owner whose orchard was raided was Henry Barker; he owned the South Acton cider mill. In South Acton, we also found mentions of games played at the Prospect Street and School Street grounds, Fletcher Corner, and at the back of Warren Jones’ place. West Acton teams played at various times at the cemetery (Mount Hope) grounds as well as fields described as Hapgood’s, Blanchard’s, and “opposite the Aldrich farm.” The teams played near-by rivals most often, of course, allowing for cheaper travel and easy attendance by friends and family. They also played teams from farther afield, including, among other places, Pepperell, Clinton, East Cambridge, and Boston’s Custom House. In the particularly ambitious season of 1897, the Acton team did a tour that included Hinsdale, NH and Rutland, VT. (Fitchburg Sentinel, September 2, 1897, page 2 and September 7, page 6) Inevitably, umpires were the source of complaints. (“Mr Hoar’s” recollections in Phalen’s History indicated that originally, there were no called strikes or ground rules and that hits were common. However, players and fans still found things to complain about.) In 1876, the Fitchburg Sentinel reported that despite inadequate umpiring, all of the players kept quiet except for Acton’s second baseman, “who, to say the least, was at times a little ‘emphatic.’” (July 31, 1876, page 3) In August of 1888, the Concord Enterprise reported that in a home game against Chelmsford, the umpiring was so bad that the Acton team forfeited the game in the sixth inning, walking off the field in protest. (August 25, 1888 page 2) More baseball drama occurred the next year; the Acton team disbanded in July, 1889. As reported in the Concord Enterprise, “The game at Lexington was the ‘straw that broke the camel’s back.’ Some of the ex-members we are informed will seek consolation in another enterprise where there is less danger from flies and foul tips.” The Maynard reporter helpfully added, “We hear the Actons have disbanded. We reckoned they would after their remarkable record at Lexington.” (July 26, 1889, page 2) Investigation showed that Lexington had won the game 29 to 1, stealing 17 bases in the process. (Enterprise, July 19, 1889, page 2) Tempers cooled eventually, and the team was back in business in the 1890s. Funding was an issue for all teams. Evidently, admission fees were charged in Boston. Fitchburg tried that, but the local newspaper complained that people were finding holes in the fence and other means to avoid paying the small price of admission. (Fitchburg Sentinel, July 31, 1876, page 3) The alternative, as in Acton, was to pass a hat at games for voluntary donations. Newspapers encouraged townsfolk to attend the games and to be generous when the hat came around. The teams also did fundraising in the off-season. Dances seem to have been a good source of revenue. For example, in December, 1888, the Enterprise noted that the Acton Base Ball Club’s fundraising ball had brought in 100 couples. One reporter called it a grand affair. (January 4, 1889, page 2) Another noted that “All had a good time, barring the dust.” (December 28, 1888, page 2). Branching out, in the winter of 1904, a benefit production of the Lothrop dramatic company was staged to aid the Acton baseball team (Boston Daily Globe, March 26, 1904, different editions pages 2 and 5). The crowd was described as “One of the largest audiences on record,” presumably meaning at South Acton’s Exchange Hall. Aside from teams that represented “Acton” or its villages, there were games between other groups. There was, for example, the very popular tradition of the Married versus Singles game. (Concord Enterprise, August 2, 1900, page 8) In June, 1911, the Enterprise announced: “This is the time of the year when the old men feel young again and the young men feel their importance. So to give expression to these pent up feelings they are arranging to crush the exuberance of each other and on the morning of July 4th they will meet in a game of baseball, the great event of the season – Married vs. Single Men – on the School st. grounds.” (June 28, 1911 page 8) Sometimes teams were created for workplace rivalries, for example pitting “the morocco shop” against “the piano stool shop players.” (Enterprise, August 2, 1900, page 8) The Acton team played a game against the Boston & Maine/ Boston YMCA team in 1907. (Concord Enterprise, July 10, 1907, page 8) By that era, there was even enough organization to have an inter-grammar school competition between the schools at Acton Centre and South Acton. (Concord Enterprise, May 15, 1906, page 8). For a while, Acton had a high school that was able to produce a team. In 1892, the Acton High School team, formerly having been known as the West Acton Stars, was looking for opponents. The manager C. B. Clark advertised that the average age of the players was 17. (Concord Enterprise, June 10, 1892, page 5) Presumably, during the period in which Acton exported its high school students to Concord, there was no longer an Acton High School team. A news item from 1911 mentioned the Acton Centre team was mostly made up of Concord High School players. (Enterprise, June 28, page 8) It is likely that the majority of them actually lived in Acton. After the new high school was built, according to Phalen, an athletic field was cleared of ledges and boulders, and a school team was again in operation in 1929. (page 336) Phalen also mentioned pictures of early teams. One, once in the possession of James B. Tuttle, showed Acton’s team wearing white caps with a blue A and wool shirts with a shield featuring buttons and a navy blue “old English A.” The Society has no photograph of that team or uniform. Another photograph that Phalen mentioned, at the time owned by Mrs. Charles Smith, was of the high school team of 1903 in navy uniforms with striped socks. (It included Harold Norris, George Stillman, Carl Hoar, Edward Bixby, Ralph Piper, William Edward, Richard Kinsley, Clayton Beach and Harold Littlefield who became a professional baseball player.) Though our baseball photograph seems to be of the same era, it must not have been of the same team. (Our picture features people of the mixed ages and different uniforms.) If anyone can help us to identify our picture, give us more information about Acton baseball, or find us copies of pictures of early Acton teams, we would love to hear from you. Please contact us. 7/3/2017 The Glorious Fourth in ActonIn honor of Independence Day, we looked back at how the people of Acton celebrated the Fourth in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The Concord Enterprise, a local newspaper, regularly reported on the celebration. It was a day for gathering with family and friends. Many businesses were closed, and most people were able to enjoy a day of leisure. The morning might start with a “horribles” parade with outlandish or comic costumes. Picnics were popular; people liked to gather at Lake Nagog, and some took the opportunity to fish there. Other people would head to Concord to picnic at Lake Walden. Some might host family reunions. None was likely to top the 1896 gala hosted by Adelbert and O.W. Mead who had a railroad car added to the local train to bring in 55 members of their family from Fitchburg to join the 60 who gathered at the Meads’ homes in West Acton.

Those craving a little more action had plenty of choices. Some entered their horses in races at Ayer or elsewhere; friends and neighbors would go to cheer them on. Baseball was a popular activity, either to play or to watch. The Acton team would often play neighboring towns on the 4th. In 1896, for example, the team played a double-header against Marlborough that drew five hundred spectators to the afternoon game. As bicycles became popular in the mid-1890s, road races were held either in Acton or neighboring towns. Unlikely though it may seem today, in 1900, there was a local yacht club that arranged a July 4th race on Lake Nagog. The newspaper reported, “The yacht race seems to have been more of a failure than a success as the boats broke down or met with some mishap near the start, D. H. Hall’s being the only one making a successful run.” On the evening of the Fourth, private citizens would often provide a fireworks display. For several years in the 1890s, South Acton was treated to fireworks by the Lothrop family. Cyrus Dole provided fireworks for a large crowd on the common in 1897 followed by cold drinks and an open house at his newly renovated summer home across from the library. Another place to view fireworks during the 1890s was Wright's Hill in West Acton. An article from 1892 mentioned people on Wright's Hill watching a hot air balloon going up and down miles away and, in the evening, seeing fireworks being set off all around the horizon. Acton’s former residents' activities on the day of the Fourth do not sound radically different from today’s. However, most people’s experiences of the night before the 4th were quite different. Year after year, “Young America” or “the small boy” would, in the name of “patriotism,” make noise throughout the evening of the July 3rd and create a ruckus at midnight. Tin horns were blown, and fireworks were set off. (“Crackers,” “cannons” and “torpedoes” were common.) As described in 1890, “pandemonium reigned supreme on the street until after midnight.” At midnight, the “boys” would often ring church bells, usually without permission. In 1897, a report in Acton Center said, “The selectmen had no special police on duty this year and the irrepressible youth took the gladsome opportunity of ringing the bells at midnight unmolested.” In 1895, the boys’ entertainment was repeatedly ringing the bell of the South Acton church and disappearing before the constable could catch them. In West Acton in 1900, the whistle at Hall Brothers’ pail factory was added to the din. It was such a long-standing custom that most people were resigned to the noise up until midnight. As one writer put it in 1892, “Well, we were all boys once, consequently were in full sympathy with the occasion.” (The writer was quite unconcerned about the sleep of the half of the population who were never boys and would not have been nostalgically remembering their days in the noisy throng.) Unfortunately, Young America was not always content to stop the noise at midnight. Writers mentioned them “making night hideous and sleep impossible” (1890) and ringing the bell “at intervals in an almost vain attempt we suppose to make the sun rise” (1891). In Acton Center, for at least two years, an impromptu “fife and drum corps” decided to stage a concert of patriotic songs after midnight. A few people spoke out about the rights of nonparticipants. One writer called the carousals disgraceful (1898), while another (1894) pointed out that “there are rights for all in this land of ours, and one may not encroach upon the other, though there be but one day in the year that calls forth such uproarious demonstration and general jubilee by the boys or the exercise of authority by law-abiding citizens. Let each respect the others’ privileges, and remember, boys, that though all gentlemen are not Americans the true American citizen is a gentleman under all circumstances.” Judging from the newspapers, gentlemanliness was not everyone's top priority on the night before the 4th. The townspeople were much more united in opposition to destruction of property. The expectation was that if the “boys” caused damage, they would fix it. In 1889, the South Acton correspondent reported “no serious damage excepting that the waves of sound created by the cannon were too much for the window glass in some residences, but the boys enjoyed the fun and no doubt everything will be made satisfactory.” In 1895, a group of young men egged Ed Banks’ house in South Acton. Mr. Banks informed them that they needed to clean it up. “It was a rather hard job, but a coat of paint will finish the work.” 1895 seems to have been a busy year; gates and other items were disarranged and an effigy was hung from the telegraph wire multiple times. In 1897, “the natives found a great display in the square in the morning, the most conspicuous object being South Acton’s ancient fire engine.... A number of wagons, single wheels and outhouses were also on exhibition.” The young men also cut the rope used to ring the bell at Tuttles, Jones & Wetherbee’s store. South Acton’s hook and ladder truck was taken in 1898, eliciting a threat from a Selectman that if the known leaders did not return it, they would suffer. (It was returned.) Even less acceptable was trouble from other towns, prompting the comment in 1893 that “when a party of men from another town come here and go to pulling down flags and demolishing chimneys, they should be severely dealt with.” A feature of old Acton’s celebrations was the prevalence of fireworks. In 1894, an enterprising South Acton postmaster decided to sell fireworks, which elicited an objection from the newspaper correspondent: “Fireworks in our post office? It would do well for the postmaster of this village to read up the law on this subject. The selectmen of a town have no right to license them to be sold in a post office. Please read what Uncle Sam says about it.” With many incendiaries going off, fire was a real concern. In 1895, a “suspicious” fire occurred on the Fourth in South Acton. This would have brought back memories of the previous July 4th when Hudson experienced a devastating fire started by boys with firecrackers. The fire wiped out 40 buildings over at least five acres in the heart of Hudson, including factories, shops, stables, five large halls, Y.M.C.A. rooms, a well-known photographic studio, the telephone station, and the post office. No one would have wanted a similar occurrence in Acton. The other major issue with fireworks was the possibility of injury. In 1889, Acton news reported that Herbert Clark, age 9, had mixed powder with dirt in a tin can and set it off; it exploded in his face. In 1895, Robert Randall lost his left hand firing a ”cannon.” An 1898 article mentioned that the year’s revelries had resulted in a few lost eyebrows. In 1899, Sheldon Littlefield was quite severely burned on his hand and face by the explosion of powder in a can. These injuries were not unique to Acton. In 1893, the local paper published a listing of the numerous “Patriotic Patients Treated at the Emergency Hospital” in Boston that year, most from careless handling of fireworks that included burns to hands and faces, lacerations, several missing fingers, and possible permanent loss of sight. In 1915, Acton celebrated differently. A South Acton committee planned a large-scale, organized 24 hours of events. Because the 4th fell on a Sunday, the celebration took place the next day. On the night of July 4th, a large bonfire of railroad ties that had been dragged to the top of a hill burned for nearly two hours. There was also a well-attended but orderly dance at the Exchange Hall. (A couple of individuals who drank or used obscene language found themselves in the lockup.) Though firecrackers seem to have been accepted in the evening (“the sound of exploding crackers made it appear like a miniature battle”), the "pandemonium" of former years was discouraged. In the early morning hours on Sunday, there was “the discharge of a few isolated fire crackers. As that was not as the plans had been arranged, the newly uniformed policeman called the patriotic spirited boys’ attention to the fact.” A big parade in the morning drew hundreds of spectators from neighboring towns. Of special note in the paper were the floats by Acton businesses; A. Merriam Co. (piano stools) showing the history of their products, Finney & Hoit (merchants) displaying a summer kitchen, and South Acton Woolen Company, showing off a large float with sections, one for live sheep, then wool, then rags, then shoddy, and finally cloth with a sign “Made from Shoddy,” a South Acton product. Grocer J. S. Moore displayed live animals and a sausage machine. A number of businesses were represented by their delivery wagons. Acton’s Road Commissioner and firemen displayed town vehicles. Other participants were the Boy Scouts, the “famous old Acton band,” and a twelve-member drum corps. A school float carried many of the young schoolchildren. A large number of Camp Fire Girls appeared with a tepee on an auto. There was a Peace Float with about 20 young ladies in white dresses. According to the paper, the suffrage auto carried several young women displaying sentiments of "Down with liquor. Don’t be a pinhead. Give woman a vote. Give women the vote and they will clean the town.” (Women apparently had finally found a way to make themselves heard on the Fourth.) Later, games and track-and-field competitions were held, and fireworks completed the day. If one stopped reading in 1915, one might think that Acton’s celebration had become completely sedate. However, the South Acton Enterprise correspondent in 1920 reported on “cannon" that were "fired off in several places in the village causing much damage by breaking glass. At the home of George Ames, School st., two windows were blown out and one at the house on the opposite side of the street. The glass in several windows at George Worster’s was cracked. It seems a great wonder that the beautiful windows of the Congregational church nearby did not suffer damage. Several windows at Acton Centre were also broken in the same way. The newly appointed policeman was right on his job and it is due to him and assistants that things were not much worse and the night made hideous.” Old habits die hard. 8/13/2016 West Acton's Football TeamWhen this photograph was donated to the Society, no one was sure that the picture was of an Acton team. The only person identified was Ernest R. Teele (front row, second from the left). He was born in 1877, so the picture was probably taken in the mid-1890s to early 1900s.

Scanning and enlarging the picture showed that some of the light uniforms are marked “W A.” Guessing that they might have been from West Acton, we searched for mention of a village team in Acton newspapers available in online archives. Available West Acton news items yielded nothing. However, newspapers of the time tended to publish “locals” from nearby towns. It turned out that for the period in question, searching the archives of the Concord Enterprise was much more productive for us. The earliest confirmation of the existence of a West Acton village football team was in the December 5, 1895 issue that reported that West Acton had played Maynard on Thanksgiving. (An October 25, 1894 issue mentioned a practice game between Maynard and “Acton.”) The September 24, 1896 issue stated that “the West Acton football eleven, Captain Wm. G. Rodway” was about to play its first game of the season against the Concord High School team. Other games were announced in the October 10, 1896 Boston Post (with Burdett College) and in the November 5, 1896 issue of the Concord Enterprise (with Maynard). The Concord Enterprise of November 12, 1896 even yielded the team’s roster at the time: Rodway (captain, back), Steele (center), Smiley (guard), Perkins (tackle), Barteaux (end), Losaw (guard), Littlefield (tackle), King (end), Holt (quarterback), Allen (fullback), and Guilford (halfback). Apparently, a Boston Daily Globe article (Sept. 27, 1896) had reported on the Concord game, listing the team as the “Actons;” the roster had seven identical players (Bateaux, Rodway, Smiley, Holt, Littlefield, Gilford and King) and four others; Blood (end), Beach (tackle), Sawyer (halfback), and Souther (fullback). The Boston Daily Globe, November 21, 1896 stated that the West Acton eleven were looking for a Thanksgiving afternoon opponent and would pay half of the expenses for 14 men, inquiries to be addressed to B. S. Holt. Maynard's news items had a different perspective. In the November 5, 1896 Concord Enterprise, West Acton's victory over Maynard was reported, along with a statement that the referee had favored the West Acton team in every decision. We found only one mention of the team after 1896, a Maynard news item in the Acton Concord Enterprise of December 2, 1897: “The football game scheduled for Thanksgiving morning between the Maynards and West Actons did not take place, as the visitors failed to show up.” Thanks to the Concord paper and an aggrieved Maynard reporter, we now know that West Acton did indeed have a football team in at least the late 1895-1897 period. There were also, at various points in time, a baseball team that played in the summers and a basketball team that seems to have played indoors at Littlefield's Hall according to a February 17, 1904 Enterprise article. We would love to know more about Acton's early teams; if you have more information or pictures from that era, please contact us. More discoveries about early Acton football can be seen here. |

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed