|

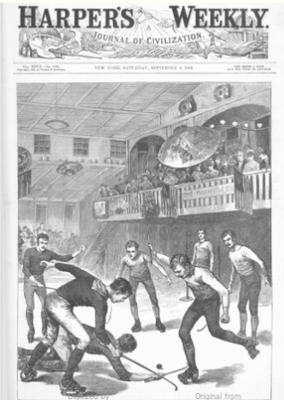

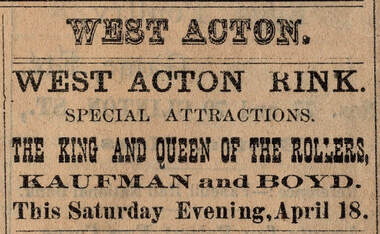

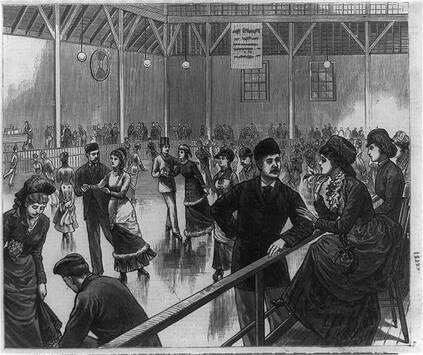

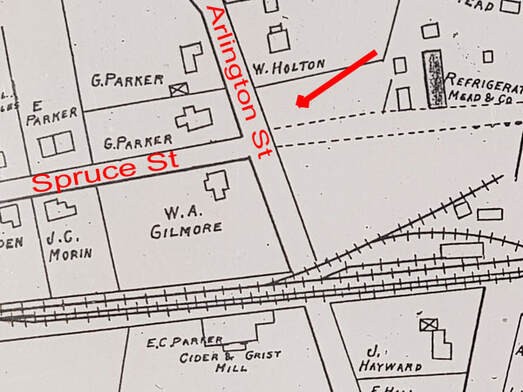

Some time ago, we came across a reference in an old newspaper to polo in Acton. Envisioning polo ponies charging through a local field, we filed that information away for another day. As it turns out, the team was actually playing a different game at a long-vanished West Acton business, a roller skating rink. In our archives, we found a description of the rink by Percy Wood. According to him, the West Acton rink was situated approximately at the southeast corner of today’s Spruce and Arlington Streets, a large rectangular building resting on posts several feet above the ground. Mr. Wood did not know the exact dates of or people involved with the rink, but he heard stories about it from Carrie (Gilmore) Durkee who lived diagonally across from it, at the site of the present-day West Acton Post Office. Because the rink was a short walk from the West Acton Depot, it was a popular spot for both out-of-town and local patrons. Conveniently, Carrie’s mother ran a boarding house and was able to provide meals and assistance to skaters, including helping female skaters into their heavy skating costumes. Wanting to verify and expand on Mr. Wood’s stories, we consulted standard Acton records. Neither the rink nor the Gilmore boarding house showed up in them. No nineteenth-century map in our collection shows a building at the rink’s location, and we did not find a mention of the rink in town reports, available directories, or tax valuations. Our access to the Concord Enterprise starts in 1888, but an online search of that paper yielded nothing. It happens, however, that our Society owns scattered issues of earlier newspapers, and luckily, the rink was mentioned in some of them, including an ad in the April 18, 1885 Middlesex Recorder [1, newspaper references at end]:  From The Champion Skate Book, 1884 From The Champion Skate Book, 1884 Clearly, the rink was operating in the mid-1880s, but we had to broaden our search to learn more. Acton’s rink was part of a much larger roller-skating phenomenon that swept the United States. Massachusetts native James L. Plimpton is credited with innovations that made roller skating a popular pastime. In 1863, he patented the quad-style roller skate (with two sets of wooden wheels that could be controlled by a skater’s shifting foot angle while all four wheels were still square on the ground, enabling easier turns and “fancy” moves than previous skates had). Plimpton then promoted the art of skating and started a franchise operation, leasing his skates to others. He also took his promotion, very successfully, to England and other countries. Over time, he improved on his own skate design, as did others; according to the Boston Globe, during the next two decades, over 300 roller skate improvement patents were filed, mostly in England and America. [2]. In Massachusetts, the Boston Globe announced in early 1876 that roller skating was gaining in popularity locally, emphasizing that participants included the “best elements of Boston society.” [3] Plimpton’s original patent ran out in 1880 and other innovations followed. Roller skating popularity exploded. Boston and Worcester had rinks, and as the craze spread, more and more local rinks were opened. The Fitchburg Sentinel reported that Clinton had a rink by 1880 and that Fitchburg’s rink would open in January 1882. [4] The Globe mentioned new rinks at South Framingham, Hudson, Leominster (two at the same time), and Ayer. [5] Unfortunately, we found nothing reported about building (or converting) a rink in West Acton or the exact date it opened for business. Photographs and illustrations of roller skating during its first phases of popularity are rare; the best we could find was this 1880 drawing of skating at a rink in Washington, DC, no doubt more fashionable than Acton’s. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)  Courtesy Hathi Trust / University of Michigan Courtesy Hathi Trust / University of Michigan Keeping a rink going meant getting patrons. Managers tried various strategies to attract crowds. They hired musicians to play during open skating hours, recruiting orchestras, bands, piano players, and even fife and drum corps. The big, open spaces could also host rallies and other large gatherings. The most commonly advertised special events at rinks were exhibitions by novelty acts, usually featuring talented, daring, unique, or very young skaters. In fact, the profit from performing apparently led some youngsters away from education, prompting New York state to pass regulations in 1885. [6] It was not long before competition was used to draw in skaters and spectators. Roller skating races were held, and large rinks could even hold bicycle races. [7] Games on roller skates were promoted, from “rink ball,” a game introduced in Brooklyn, New York and played with hands [8], to “polo on roller skates” played with a hard ball and sticks similar to those used in field hockey, but thinner. This polo played between stick-wielding skaters was new, and the game’s structure, equipment, and rules were still being worked out during the West Acton rink’s existence. Early play seems to have favored “rushing” with the ball toward the other team’s side. When a player rushed with the ball, the opposing team had time to line up in front of their “cage” and wait for the rusher to arrive. Passing, an innovation mentioned in a November 1885 Globe article, might catch the defense off guard. An attempt to make face-offs fairer had the referee throwing the ball against the side of the rink. [9] Other attempted innovations involved painting a stripe on the ball, using alternate materials for skate rollers such as cork, and installing netting to protect spectators. [10] Rival leagues had varying requirements. A Herald article described some of the rules set down by the New England Polo Association for its teams in October 1885. The game was to be played with six players on a side, competing for three goals out of five. There were referees who could impose fines for actions such as wearing extra padding, rough play, spitting on the floor, interfering in a dispute, tampering with skates or using profane language. (Fines went to the rink manager.) The referees could also expel players if necessary. [11] Rules seem to have been needed. The Globe reported that New Hampshire rink managers were disbanding their clubs for doing too much brawling. [12] Spectators occasionally were “disgraceful” as well. At one Waltham game, the crowd was calling out for bodily harm to be perpetrated not only on the opposing team but also on the referee. In addition, local fans were apparently helping out by punching an opposing player when he got to the corners of the rink. [13] Fortunately for our research, intense interest in roller skating and polo in the mid-1880s led Boston newspapers to report on action in outlying areas. From them we were able to learn something of what went on at the West Acton rink. The first mention that we found was the Boston Globe report on June 22, 1884 that Jessie Lafone (a teenager well-known for graceful and skillful skating) had performed an exhibition there the previous evening. [14] The first game of “polo on skates” played at the West Acton Rink was between the West Actons and the South Actons on August 16, 1884. West Acton’s “home team,” in their new uniforms, won the game with three straight goals in three minutes. (The object of the game was to reach three goals out of five.) Such a short show being bad for business, the proprietor asked the captains for a rematch. The second game was better contested, taking 15 minutes to end with a score of West Acton’s three goals to South Acton’s two. Player George E. Holton was singled out as an excellent rusher with “astonishing” accuracy in hitting the ball into the goal. [15] During the fall of 1884, the West Actons’ matches appeared in the news. The West Actons and South Actons met again on September 27. [16] Other matches reported in various papers were against the Websters of Boston, the Hudsons, the Leominsters, the Wekepekes (Clinton), the Alphas (South Framingham), and the Fairmounts (Marlborough). [17] The team joined the newly formed Union Polo League in November with Marlborough, Leominster, Clinton, South Framingham and Hudson. [18] The Globe mentioned the West Acton team having a game in the week of Dec. 21 1884. [19] Then without explanation, on Dec. 28, 1884, the Globe announced, “Owing to the disbanding of the West Actons and their withdrawal, the Hudsons lose two games, and the Wekepekes and Naticks lose one each.” [20] We have not found out the story of what happened to the West Acton team. Perhaps they were not performing well at that point, as the Globe had reported on the 16th that “The game at West Acton last Saturday evening, between the Wekepekes and West Actons, was won by the former in the remarkably short time of 2 minutes 5 seconds.” [21] The team also lost to the Naticks by allowing three straight goals on December 18th. [22] Perhaps West Acton had lost some players to other teams or to other pursuits. Competition between rinks was increasing; the Herald announced on December 14 that “Rinks are being opened at the rate of almost two a day.” [23] Close to home, Maynard’s new rink was about open. [24] Author Percy Wood did not know who owned or managed the rink, but our newspaper searches revealed that the manager was Thomas O’Brien. [25] He seems to have been quite enterprising. For example, West Acton’s innovative thinking was singled out in the Globe on Oct. 26, 1884 when the rink held a “Campaign race” in which all the presidential candidates were impersonated. To win, the impersonator had to reach the rink’s “presidential chair” first. The People’s Party was the winner. The Globe mentioned that “The Belva of the occasion was gorgeously gotten up,” a reference to suffragette Belva Ann Lockwood of the newly-formed Equal Rights Party. [26] Our own newspaper collection showed that Thomas O’Brien was busy finding ways to keep the rink excitement going in West Acton, even without a “home team” to cheer for. On February 27,1885, the Littleton Courant reported on a party on Feb. 14 at which all patrons received a valentine, an exhibition of the Milo Brothers’ “fancy skating and other feats,” and a “popular orange race,” (in which contestants would alternate grabbing an orange from a crate at the center of the rink and doing laps without dropping the oranges retrieved already). [27] A stained and torn Acton Patriot (April 24) in our collection tells us that J. F. Kaufman and Maud Boyd’s waltzing and fancy skating were “a marvel of grace and beauty, showing long and careful practice.” They called themselves “The King and Queen of the Rollers,” a title apparently claimed by many. The same Patriot reported that “Next Saturday at the rink there will be a gold medal race between E. E. Handley and George E. Holton. An interesting contest expected.” [28] Twice during 1885, the West Acton rink hosted games involving the Niagara female polo team, who seem to have been a good draw. [29] Thomas O’Brien had not given up on local polo teams at that point, because the April 24, 1885 Patriot also announced that “Rink Manager O’Brien has some gold medals he proposes to put up for competition between clubs formed in Acton, West Acton and South Acton and possibly Maynard. This is an interesting, exciting and scientific game. The medals will be of substantial style and worth playing for. Boys, get your sticks and uniforms ready.” [30] Sadly, we have no more local papers of the period to tell us what happened. When the Union Polo League planned their organizational meeting for the fall season on October 19, the West Acton rink manager was included. The Herald reported that the South Actons would be one of the teams, but when the League’s membership was announced the next week, it only included clubs from Arlington, South Framingham, Clinton, Hudson, Marlboro and Maynard. [31] We were not able to find any mention of a South Acton team’s games. The rink had other problems besides lack of local polo teams. Harmless as roller skating seems to us today, the pastime encountered strong objections from some members of the clergy including the minister of West Acton’s Baptist church Rev. C. L. Rhodes. According to Percy Wood, Rev. Rhodes “strongly warned the young people of [his] church to stay away from what he evidently regarded as a den of iniquity.” Presumably, some of his flock listened to his warnings and did indeed stay away. Others seem to have ignored him. One young man who later became a pillar of the community obeyed his preacher by avoiding the West Acton rink and skating elsewhere instead. Rev. Rhodes was not alone in his condemnation. The Lowell Sun reported that “The game of polo originated in the modern den of depravity known as the skating rink, and it has proved itself worthy of its low and demoralizing source.” [32] Morality was not the only concern. The Globe quoted a doctor, who, in trying to understand the cause of a large increase in pneumonia deaths, blamed roller skating. Acknowledging that he was just speculating and that people died of pneumonia without roller skating, he went on to say, “But I can say with certainty that such exposure as the roller skating mania produces is likely to produce pneumonia. Here are, say 20,000 young people going every night to skating rinks or balls. They indulge in violent exercise in heated rooms and then go out into the chill air, possibly thinly clad, and the result is fatal inflammation of the lungs.” A young woman who danced vigorously and then went outside in her ballgown would be considered “very indiscreet,” yet skaters, finding the cool air pleasant, apparently made a habit of walking “through the chilly streets while yet perspiring from their violent exercise.” [33] It is hard to say what effect such opinions had on the West Acton rink. Though it survived 1885, we have found no mention of it after that. The roller skating craze had probably peaked by then, and increased competition undoubtedly caused a shakeout in the market. Ads started appearing for rink sales. In July, 1885, an ad for a rink mentioned “good reasons for selling.” [34] In November 1885, a “first-class skating rink” an hour from Boston was looking for an infusion of capital, and in December the Globe advertised a skating rink with fixtures “in large town for 1/3 value; good chance to make money; no competition.” [35] Even more dramatically, the Globe reported that a skating rink built for $17,000 the previous year with a white marble “underpinning,” and $4,000 of skates had been offered for sale at $800. [36] After the West Acton rink closed, it evidently stood empty. Percy Wood reported that the rink building “had one narrow escape from destruction from fire on a Fourth of July during which many of the citizens were out of town. A fire broke out in the storage shed located between the railroad tracks and the present Spruce Street. Fortunately, the fire was confined to the area in which it started, despite the lack of manpower and only the most primitive fighting equipment. The rink was, however, seriously threatened and was saved largely by the efforts of a man who was nearly exhausted by his exertions but was revived by a bowl of ginger tea supplied by a kindly neighbor.” Newspaper searches, unfortunately, did not turn up information about that fire, so we were unable to confirm the date. Percy Wood continued, “Instead of being left to stand as an eyesore, the building was taken down by Mr. John Hoar, the well known contractor and builder, and was used to construct a house on Central Street in West Concord. But on the original site Arlington St. in West Acton, there is not a trace of what was once a popular amusement center.” Whenever the West Acton rink disappeared, we know that sport and exercise in Acton continued. The Concord Enterprise reported that the Acton Cycle Club polo team went to Concord and defeated the home team’s “gentlemanly fellows” in February 1895. [37] That game may have been played on ice, as “ice polo” teams were forming in the 1890s. Toward the end of that decade, West Acton had another chance at indoor roller skating. The ever-enterprising Hanson A. Littlefield announced in the January 6, 1898 Concord Enterprise that Littlefield’s Hall had been fitted for roller skating. Open skating would cost ten cents, and the facility could be rented by private parties. [38] We do not know how long that lasted, but the Hall itself burned down in 1904. The West Acton roller skating rink might have completely escaped our notice if it had not been for Percy Wood’s documenting Acton memories. Thanks are also due to organizations that are digitizing and sharing old newspapers. If anyone has pictures or mementos of West Acton’s roller skating rink or Acton’s polo teams that they would be willing to share, donate or scan, we would be very grateful to add them to our archives. Sources Newspaper References: [1] Middlesex Recorder, Apr. 18, 1885, page 3 (Jenks Library) [2] Boston Globe, March 23, 1885, p.4 [3] Boston Globe, Jan. 27, 1876, p. 5 [4] Fitchburg Sentinel, April 7, 1880, p. 3; Dec. 16, 1881, p. 3 [5] Boston Globe, Nov. 18, 1883, p. 6; Jan. 20, 1884, p. 2; March 23, 1884, p. 6 [6] Boston Globe, Apr. 16, 1885, p. 8 [7] Boston Globe, Nov. 27, 1885, p3; Mar. 24, 1887, p. 5 [8] Boston Globe, Jan. 14, 1878, p. 2 [9] Boston Globe, Nov. 19, 1885, p. 3 [10] Boston Globe, Jan. 20, 1884, p. 2; Mar. 23, 1884, p. 6 [11] Boston Herald, October 14, 1885, p. 2 [12] Boston Globe, Jan. 31, 1885, p. 4 [13] Boston Herald, Nov. 25, 1885, p. 3 [14] Boston Globe, June 22, 1884, p. 6 [15] Boston Herald, Aug. 17, 1884, p. 2; Boston Journal, August 19, 1884, p. 3 [16] Boston Journal, Sept. 30, 1884, p. 4 [17] Boston Herald, Aug. 31, 1884, p. 2; Boston Globe, Oct. 24, 1884, p. 2; Boston Herald, Dec. 7, 1884, p. 7; Worcester Daily Spy, Dec. 8, 1884, p. 3; Boston Herald, Dec. 14, 1884, p.4; Boston Globe, Dec. 19, 1884, p. 2 Boston Globe, Dec. 21, 1884, p. 10 [18] Boston Journal, Nov. 24, 1884, p. 3; Boston Globe, Nov. 23, 1884, p. 15 [19] Boston Globe, Dec. 21, 1884, p. 10 [20] Boston Globe, Dec. 28, 1884, p. 10 [21] Boston Globe, Dec. 16, 1884, p. 6 [22] Boston Globe, Dec. 19, 1884, p. 2 [23] Boston Herald, Dec. 14, 1884, p. 4 [24] Boston Globe, Dec. 21, 1884, p. 10 [25] Boston Globe, Nov. 23, 1884, p. 15; Nov. 30, 1884, p. 10 [26] Boston Globe Oct. 26, 1884, p. 14 [27] Littleton Courant, Feb. 27, 1885, p. 1 (Jenks Library) [28] Acton Patriot, April 24, 1885, p. 4 (Jenks Library) [29] Boston Globe May 24, 1885, p. 6; Boston Herald, Oct. 11, 1885, p. 15 [20] Acton Patriot, April 24, 1885, p. 4 (Jenks Library) [31] Boston Herald, Oct. 18, 1885, p. 7; Boston Globe, Oct. 24, 1885, p. 2 [32] Lowell Sun, March 28, 1885, p. 4 [33] Boston Globe, Mar. 19, 1885, p. 6 [34] Boston Globe Jul. 20, 1885, p. 3 [35] Boston Globe, Nov. 17, 1885, p. 7; Dec. 30, 1885, p. 7 [36] Boston Globe Sept. 25, 1885, p. 6 [37] Concord Enterprise, Feb. 7, 1895, p. 4 [38] Concord Enterprise, Jan. 6, 1898, p. 8 Other Sources: Though these references do not mention Acton, they give great detail about the history and state of roller skating and roller polo at the height of the 1880s boom:

Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed