|

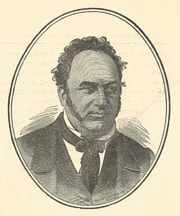

2/3/2018 Abolition and Reverend Woodbury Rev. Woodbury Rev. Woodbury A question about possible Underground Railroad sites in Acton led us to investigate, more generally, anti-slavery sentiments and activity in Acton. Because our local newspaper access starts after the Civil War, we doubted that we would find out much. Fortunately, William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper The Liberator is available for research and gave us a surprising amount of information about what was (and perhaps was not) happening for the cause of abolition in Acton in the 1830s – 1850s. Most of the material related to James Trask Woodbury, minister of Acton’s Evangelical Society starting in 1832. The earliest Liberator references to Reverend Woodbury were quite complimentary. When the Middlesex County Anti-Slavery Society was formed, he was chosen as one of its counsellors (Oct. 11, 1834, p. 3). He became Secretary the next year (Oct. 17, 1835, p. 3). He spoke against slavery at various gatherings, including a convention in Groton, meetings of Sudbury’s female anti-slavery supporters, and the New-England Anti-Slavery Convention in Boston in May, 1835 (May 30, p. 3). He hosted Anti-Slavery Society meetings and speakers at his church, including “Mr. Thompson” (Jan. 31, 1835, p. 3) and Charles C. Burleigh who described him as “the excellent minister, our true-hearted abolitionist brother, Mr. Woodbury.” (March 28, 1835, p. 2) He was later called "one of the early movers in the anti-slavery agitation”. (March 4, 1853, p. 3) At the New England Anti-Slavery Convention in July, 1836, Rev. Woodbury spoke impassionedly about the moral duty of the church to stand against slave-holding as a sin and a crime (July 23, 1836, p. 1). In July 1837, Rev. Woodbury was asked to speak at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s July 4 celebration, though he declined the opportunity. (July 7, 1837, p. 3) He was quite obviously held in high esteem by William Lloyd Garrison and his compatriots. However, that was about to change. Hindsight and a very different worldview make it difficult for us today to relate to the mindset of ministers of the 1830s, but to understand what came next, we have to recall that it was a time of religious upheaval. Preachers of many viewpoints had been upending the status quo. More orthodox ministers were trying to hold onto their “flocks” and guard them against what they saw as spiritually disastrous errors. Some Massachusetts clergymen had grown increasingly disturbed by some of William Lloyd Garrison’s non-conformist religious views and his criticisms of established societal and political structures (including churches). Apparently, the tipping point was Garrison’s support of the Grimke sisters, whose anti-slavery lectures were attracting mixed-gender audiences and generating disagreements about the role of women in society. The Congregational General Association of Massachusetts issued a letter in June 1837 to be read in Congregational churches, affirming the minister as people’s spiritual guide and leader, discouraging speakers from presenting “their subjects within the parochial limits of settled pastors without their consent”, and urging women to be unostentatious and modest, rather than assuming “the place and tone of man as a public reformer.” (Aug. 11, 1837, p.1) This Pastoral Letter, coupled with an “Appeal of Clerical Abolitionists” criticizing The Liberator for its treatment of the clergy (Aug. 11, 1837, p. 2-3) elicited a barrage of letters in various newspapers, many printed or reprinted in the pages of The Liberator. Into the fray stepped Acton’s Reverend Woodbury. He wrote a long letter in support of the Clerical Appeal that was published in the New England Spectator and reprinted on the front page of The Liberator (Sept. 1, 1837), including: “I am an abolitionist... but I never swallowed Wm. Lloyd Garrison ... I became alarmed some months since, for the cause of abolition in such hands ... he is determined to carry forward and propagate and enforce his peculiar theology. He is not satisfied to teach his readers and hearers the truth as he holds it in reference to slavery and its abolition, but he must indoctrinate them, too, on human governments and family government and the Christian ministry and the Christian Sabbath, and the Christian ordinances. Slavery is not merely to be abolished, but nearly everything else. ... Desert the cause of abolition? No—never. But desert Mr. Garrison, I would, if I ever followed him. But I never did. I once tried to like his paper – took it one year and paid for it, and stopped it ... What there was of pure abolition in it I liked. Like the veal in a French soup, I liked it – the whole of it – but I could not swallow the onions, and the garlics, and the spice, and the pepper. ... P.S. No doubt, if you break with Garrison, some will say, ‘you are no abolitionists,’ – for with some, Garrison is the god of their idolatry. He embodies abolition. He is abolition personified and incarnate.” There were many other letters, but Rev. Woodbury’s made quite a stir. Probably because of Garrison’s extensive answer in The Liberator, Woodbury’s name came to be associated with the ministers who wrote the Appeal. From the tone and depth of the response, it is clear that Garrison felt betrayed by someone he thought was a brother in the cause. Leaving aside much in the rejoinder, we can learn from it how Rev. Woodbury’s thinking about abolition evolved. Garrison remembered that Woodbury had dated his own conversion to abolitionism to a time when he stood by Washington’s tomb, but unfortunately the details of the story were not mentioned. According to Garrison, Rev. Woodbury had followed Garrison in his thinking “from the colonization to the abolition ranks; from gradual to immediate emancipation; from associating with slaveholders as Christians to repudiating them as thieves and robbers, and ‘sinners of the first rank.’... I heard nothing of you in this cause till it had found a multitude of supporters.” (Sept 1, 1837, p. 3) Some in the national American Anti-Slavery Society felt that the disagreement between the clerics and Garrison was a local and unfortunately personal dispute. They did not take a side, probably hoping that the anger would die down and that the anti-slavery cause would not be split. Unfortunately, that was not the case. In the October 27, 1837 Liberator (p. 3), some “personal interrogatories” were published questioning the motives of some of the ministers involved in the controversy. Rev. Woodbury appeared prominently: “Is it, or is it not true, that Rev. J. T. Woodbury, of Acton, is brother of Hon. Levi Woodbury, Secretary of the Treasury? Is it, or is it not true, that the Hon. Secretary is fishing for the Vice-Presidency? And is it, or is it not true, that the active abolitionism of his brother at Acton, has been deprecated as tending to injure the political prospects of the Secretary?” The Liberator noted that such interrogatories were annoying some readers and should be used carefully. But given the possibility of people all over the country being influenced by “certain suggestions from Boston, and Acton, and Andover,” it was a public service to answer such questions. Under the circumstances, the reporting might not have been objective. However, we did learn that Rev. Woodbury’s brother was indeed Levi Woodbury, who at various points was New Hampshire governor, senator, Secretary of the Navy, Secretary of the Treasury, and later, Supreme Court Justice and presidential hopeful. (As it turns out, Rev. Woodbury had actually studied law with his brother Levi after graduating from Harvard in 1823. He was admitted to the bar and practiced in New Hampshire before he decided to become a minister.) The article related that Rev. Woodbury had told “an influential abolition friend – ‘I am not going to be so conspicuous in the anti-slavery cause as I have been. My brother’s family complain that I am injuring his political prospects, and I have no idea of being in the way, by acting so prominent a part in this case’ !” The writer seems not to have discovered the Woodburys’ brother who lived in Mississippi. That would certainly have been mentioned in the interrogatories; another minister’s Southern connection was noted. The article did report the discovery that Rev. Woodbury had spoken warmly about The Liberator from the pulpit in the past, so he must have “swallowed” Garrison. One might have hoped that over time, some of the bitterness would have died down. Rev. Woodbury continued to be involved in abolitionist activities, authoring a letter about a meeting in Concord that was published in The Liberator (Dec. 21, 1838, p. 3). He was still involved in the Middlesex County Anti-Slavery Society in 1839; it met in his meetinghouse in Acton in July that year. Unfortunately, on that occasion, the schism came directly to Acton. There was dissension about whether or not men should be required to vote in political elections and, even more divisively, about the right of the women present at the meeting to vote on matters affecting the Society. Eventually, the Society’s Secretary (Rev. J. W. Cross of Boxborough) resigned, and a walk-out followed by certain members, including Rev. Woodbury. Evidently, they “withdrew for the purpose of forming a new Society.” (July 26, 1839, p. 3) Rev. Woodbury did not turn away from the cause of abolition. His was the first name on an 1840 Acton petition for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade in the District of Columbia. Evidently, he became an active supporter of a new abolition society that proposed to “abolish this great wrong at the ballot-box,” and he did “earnest work for the success of the party he professed to believe to be right.” (March 4, 1853, p. 3) However, his apparently outspoken opposition to “Garrisonism” (as it was understood at the time) continued to draw ire from The Liberator. On July 27, 1841, Mr. Garrison and others met with the Middlesex County Anti-Slavery Society in “Chapel Hall, Acton”. (Aug. 6, 1841, p. 3) At the meeting, four resolutions were adopted unanimously. Along with important items (calling for the end of slavery in the District of Columbia and of laws preventing interracial marriage), a resolution passed that: “James T. Woodbury, of Acton, a professed abolitionist, and formerly among the foremost in rebuking those clergymen who refused to give any countenance to the anti-slavery movement, in refusing to read from his pulpit a notice of the quarterly meeting of this Society, has manifested toward our organization as bitter and hostile a spirit as has ever been shown by the pro-slavery clergy of the land, and identified himself, in this particular, with the feelings and wishes of southern taskmasters.” This was surprisingly strong wording. One can only imagine that perhaps Rev. Woodbury had been employing his considerable oratorical skills in a similar manner from the pulpit. In 1852, The Liberator reported that the “warlike minister” had for years held up Mr. Garrison as “an infidel and a madman.” (June 11, p.3) Reading The Liberator was fascinating, because it yielded so much unexpected information about how the debates over abolition and other societal changes played out in Acton. However, the reporting seems unlikely to have given us a full (or perhaps fair) picture of a minister who served in Acton for twenty years and whose departure to Milford in 1852 was at his own request, not his congregation’s. Fletcher’s portrayal in Acton in History (pages 290-292) reveals James T. Woodbury as more of a “character” than one would expect from stories in The Liberator. His preaching was effective despite (or perhaps because of) a lack of notes and learned references. “Few have carried into the pulpit preparations so apparently meagre... He simply had the lawyer’s brief, a small bit of paper, which none but himself could decipher, and he with difficulty at times.” He was a large, broad-shouldered man with a commanding presence who could modulate his voice very effectively and tap into listeners’ emotions. He had a way with words and stories and was frank in expressing his convictions, unconcerned with whether others agreed or not. “People gave him credit for meaning what he said, even if they did not agree with him.” Fletcher collected anecdotes about Rev. Woodbury that are worth mentioning to round out impressions of the man. It was said that he liked to live outside of Acton village so that “he could shout as loud as he pleased without disturbing his neighbors.” He wore clothes considered unusual at the time and “drove his oxen through the village in a farmer’s frock, with pants in his boots. Because he had a mind to.” He liked the choir in his church because it was large and included women (his wife among them). “He got tired of this all gander music when in college.” These stories hardly fit the image of the dour cleric that one envisioned from The Liberator. Reverend Woodbury was elected to the Massachusetts Legislature in the 1850-1851 period, evidently with the aim of obtaining financial aid to erect a monument to the memory of Acton’s minutemen who died April 19, 1775. Evidently, his legislative colleagues were at first unenthusiastic, but a two-hour speech by Rev. Woodbury managed to tap into their patriotic emotions and secure the funding. When the monument was dedicated on October 29, 1851, Rev. J. T. Woodbury was given the honor of being president of the day. Having left his mark on Acton in many ways, Rev. Woodbury left for Milford, Massachusetts where he was installed as Congregational minister on July 15, 1852. He was mentioned in The Liberator as having given a speech at a large anti-slavery meeting in Hopedale (Aug. 11, 1854, p.3) that was also attended by Sojourner Truth and Garrison allies Charles C. Burleigh and Henry C. Wright. Rev. Woodbury served the Milford church until his death in 1861 at age 58. As had been his wish, he was buried with his son in Woodlawn Cemetery, Acton.

From a distance of almost two centuries, the dispute between James T. Woodbury and William Lloyd Garrison seems quite unfortunate. Though both were committed to the anti-slavery cause, other issues and personal animosities came between them. A letter to The Liberator (signed “Saxon”) described Rev. Woodbury as “one of those strong, ruling natures, which take the lead of affairs, and mould others to their own purposes.” (March 4, 1853, p. 3) Regardless of what one thought of Rev. Woodbury's stances on certain issues, his conviction and his ability to influence were undeniable. One has to think that despite their differences, William Lloyd Garrison and James T. Woodbury had that in common. Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed