|

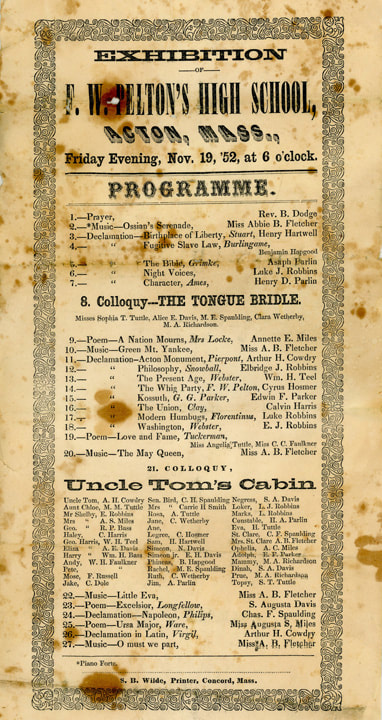

In the years before Acton had a high school of its own, students wanting to further their education needed to take opportunities where they could be found. In Acton’s early days, young men were usually the ones to seek education beyond the schoolhouse; they might be given advanced training or prepared for college by a learned individual, often the town’s minister. In the 1800s, more opportunities arose for young men and young women; some might board at private academies or, as time went on, commute to a nearby high school. In the early 1850s, Acton’s advanced students had the option of studying for short periods at a privately-run advanced school. Our Society’s collection includes a program for an exhibition of F. W. Pelton’s High School in the center district of Acton, starting at 6 p.m. on November 19, 1852. It must have been a long evening; there were twenty-seven items on the agenda, including two dramatic pieces. The Exhibition As evidence of what was going on in the minds of young Actonians in 1852, the “programme” is a revealing document. Even in a small town, there was obvious interest in the issues affecting the country as a whole. Abolition was the foremost theme of the evening. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, though now criticized because of its racial stereotypes, was hugely influential in raising awareness of the evils of slavery. It had been serialized starting in June 1851 but had only been out in book form since March 1852. An early performance in Acton, featuring over 30 performers, would have been a notable event. The song “Little Eva” that followed the performance was based on the book and had recently been published in Boston. Other items on the program that involved the issue of slavery were “declamations” on Anson Burlingame’s opposition to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, Grimke’s “Bible”, presumably Angelina Grimke’s “Appeal to the Christian Women of the South” (1836), and Henry Clay’s attempts to save “The Union” without war. Other declamations had as their subjects Daniel Webster’s writings on Washington and on “The Present Age,” Lajos Kossuth, a Hungarian leader whose words had managed to catch the popular imagination in the United States, Napoleon, and the Whig Party (written by the schoolmaster himself). We were not able to identify all of the items performed. Ames’ “Character” may have referred to one of Fisher Ames’ writings, but there is not enough information to be sure. Stuart’s “Birthplace of Liberty” and Snowball’s philosophy were similarly hard to pin down. In online searching, some of the titles are now overshadowed by later writings and events. A search for Snowball’s “Philosophy” led to many references to George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Searching for “A Nation Mourns” brought up references to Lincoln’s assassination, and “Modern Humbugs” yielded P. T. Barnum’s book The Humbugs of the World, both dating from the 1860s. (“Modern Humbugs” by Florentinus may have been a tongue-in-cheek piece written by the schoolmaster; see the section on him below.) Drama, songs, and poetry were easier to find. “The Tongue Bridle” was a dramatic piece for “four older girls” published in Boston in 1851. Thanks to the Library of Congress’ Music Division, we were able to find the 1849 Ossian’s Serenade, the 1851 Oh, Must We Part to Meet No More?, and The Green Mt. Yankee, a Temperance Medley, published in Boston in 1852. Once we had navigated past references to Led Zepplin songs, we were able to find an 1848 song by I. B. Woodbury that set Tennyson’s poem "The May Queen" to music. Henry Theodore Tuckerman’s “Love and Fame,” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1841 “Excelsior,” and Henry Ware, Jr.’s “To the Ursa Major” can all be found in online poetry collections. The only item with a strictly Acton theme was Pierpont’s poem “Acton Monument.” One wonders if the entire poem describing the events of April 18-19, 1775 was recited; even at its debut, the audience became impatient with its length. Rev. John Pierpont of Medford presented the poem at the celebration of the completion of Acton’s Monument in 1851. The reverend had the misfortune that day of being slated to recite after an hour-long address by Governor George S. Boutwell and just before the meal was served. Hungry attendees started eating during his recital of the poem, and the clatter of utensils clashed with the sound of the reverend’s voice. Apparently, he got quite upset. Acton’s Rev. Woodbury, who could have tried to quiet the crowd, instead said a quick grace and let the dinner officially begin. Boutwell’s Reminiscences quote Woodbury as telling the poet, “They listened very well, ‘till you got to Greece. They didn’t care anything about Greece.” (page 130) By that point in the day’s speeches, the audience might have been losing enthusiasm for Acton as well. Later, obviously having calmed down, Rev. Pierpont commented on the situation that “Poets at dinners must learn to be brief, Or their tongues will be beaten by cold tongue of beef.” [Boston Evening Transcript, Oct. 30, 1851, p.1) The audience at Pelton’s High School Exhibition had to have been tired by the end of the evening. After speeches, songs, poetry, and drama, Arthur Cowdrey capped off the event with a declamation in Latin from Virgil. Presumably this was to wow the audience. (Clearly, Mr. Pelton was able to teach his students a range of subjects.) Miss A. B. Fletcher performed her fourth musical number, and the evening was finished. Acton’s Private High Schools We had thought that perhaps F. W. Pelton’s high school was unique to him. However, a speech by one of his former students explained that Acton’s private high school, at least for a time, was an annual occurrence taken on by a college student during a break from his studies. It allowed a college student to earn funds and benefited the townspeople by supplementing their publicly-funded education. Eben H. Davis told Acton’s high school graduates in 1895 that: “When I was a boy, the only high school in the town was a private enterprise, held but a few weeks in the fall, in the centre of the town, and kept by some college student to eke out his college expenses. There was no orderly course of studies, but each student selected such branches as his fancy dictated or friends advised, for which he paid his own tuition. In this way it was possible to obtain a smattering of Latin or Greek, an introduction to the elements of science, and some knowledge of mathematics. But, in order to fit for college, I had to attend an academy, one hundred and fifty miles from home. ... I would by no means speak lightly of the schools of my boyhood days... Nor were those brief terms of high school studies without influence. They opened up to us new lines of thought, and the personality of the teachers, fresh from college and imbued with zeal for a higher education, made a strong impress. It was through contact with such influences that I was inspired with an ambition to go to college.” (Town Report 1896, p. 83-84) Contrary to what we had expected, this high school was not simply for older students who had progressed beyond the curriculum of Acton’s schoolhouses. Some of the students were fairly young. From reading school committee reports of the time, we discovered that the public schools in the early 1850s had a summer term and a winter term; the private school in autumn obviously filled a gap, not just of higher learning, but in a time of the year when scholars would not have been able to continue their studies. We have not yet found all of the college students who led a private autumn high school in Acton, but we did find mention of a Mr. Cutler who seems to have run a popular private school in the fall of 1848. The school committee report of 1848-1849 alludes to the difficulties of a Winter Term teacher, Dartmouth College graduate Mr. Whittier, who had come with great recommendations. “Mr. Whittier, in assuming the duties of his school, was somewhat in the position of the poor king who followed the people’s favorite, when nature’s poet said, ‘As when a well graced actor leaves the stage, All eyes are idly bent on him that enters next.’ Mr. Cutler in his select school had won all hearts, both of parents and children, and they thought his like would never appear again. This feeling among the leading scholars was a great injury to the school, which ought to have been one of the best.” We will set aside research into Mr. Cutler’s identity for another day. If anyone knows more about him or other Acton private school teachers, please let us know. The 1852 Schoolmaster, F. W. Pelton We know very little about F. W. Pelton’s brief time in Acton. We were able to identify him because the 1853 school committee report mentioned hiring F. W. Pelton “of Union College” to teach the Centre School in the winter term 1853 after he had run a private school in Acton Center in the fall of 1852. The mention of Union College allowed us to confirm that he was Florentine Whitfield Pelton, born in Somers, CT on April 23,1828 to Asa and Lois Pelton. According to Jeremiah M. Pelton’s Genealogy of the Pelton Family in America (page 477-478), Florentine Pelton left home at a young age, supposedly taught in New Jersey, and furthered his studies at Wesleyan Academy in Wilbraham, MA and Union College. The year in which F. W. Pelton taught in Acton was an unusual one. At town meeting the previous April, Acton had elected a School Committee of three clergymen. All three had left town by the end of the year. (One was Rev. J. T. Woodbury, discussed in a previous blog post.) Ebenezer Davis and Herman H. Bowers wrote the subsequent School Committee report. Two of Ebenezer Davis’ children had attended Pelton’s fall High School. F. W. Pelton’s winter term at the public school seems to have been much less successful than his private school experience. (School committees in the nineteenth century could be merciless in their reports, and teachers had no ability to present their viewpoint.) It is likely that having 52 students of varying ages, with an average attendance of 44, was a contributing factor, as well as the fact that the curriculum would not have been driven by students’ interests as it was in the private school. Pelton may already have been in career transition during his Acton period. He soon made the law his career, studying with C. R. Train and at Harvard Law. He was admitted to the Middlesex County bar in 1855, and practiced first in Marlborough and then in Boston. He married twice, first to Laura M. Buck, a graduate of the State Normal School at Framingham, MA, on Dec. 18, 1855. The couple had two children before Laura died from complications of childbirth in 1860 in Newton where they were living at the time. Pelton married Mary Reed Whitney in Waltham, MA on Nov. 20, 1862, and the couple had eight more children. In addition to practicing law, Pelton dealt in real estate and was responsible for the construction of a number of houses in Dorchester, MA. Toward the end of his life, he retired from the law, focusing on various business ventures. He settled in Dedham, MA where he died of “chronic peritonitis,” probably a complication of his diabetes, on June 25, 1885 in Dedham. We found no reference to Florentine W. Pelton’s time in Acton in newspapers, family histories, or obituaries. However, his experience there may have led to this thought from the report of the Newton Grammar School Sub-Committee, of which F. W. Pelton was a member in the 1860s: ”If the varied, difficult and exhausting work of the school-room could be understood at home, there would be more sympathy and less fault-finding with the teacher.” (Annual Report, Mass. Board of Education, Vol. 27, 1864, p. 92) Indeed. The Exhibition Participants There are many names on Pelton’s 1852 Programme, but there were only a few that we could not track down. Perhaps those students were not residents of Acton; the school committee report of 1853 mentioned that some private school scholars in the past had come from out of town. (p. 5) In the rest of the cases, we found individuals who would have been between twelve and eighteen in the fall of 1852. Among the sources we used were school committee reports; it is not surprising to find that young scholars who were enrolled in an extra school in the fall of 1852 were also commended for excellent attendance at the public schools. As best we can reconstruct it, the following is our list of Pelton’s high school exhibition participants:

We would like to acknowledge Elizabeth Conant (1929 - 2013) whose years of work at Jenks Library are still yielding insights for us and whose helpful notes on Pelton’s Programme got us started on this project. Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed