|

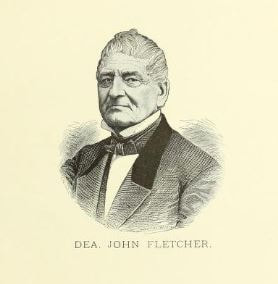

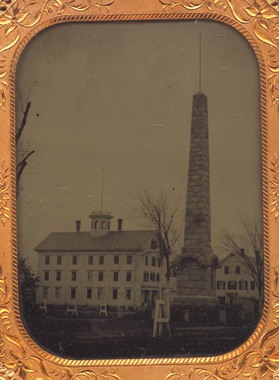

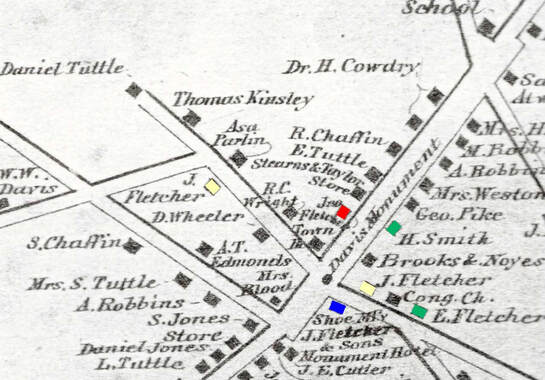

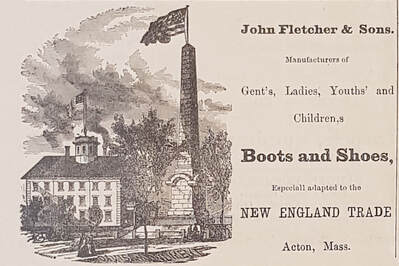

6/15/2019 John Fletcher, Not Just About Shoes John Fletcher & Sons Boots John Fletcher & Sons Boots Recently, the Society received the generous donation of a remarkably well-preserved pair of boots from the factory of John Fletcher and Sons. John Fletcher’s name was very well-known in Acton in the 1800s, and his “Boot and Shoe Manufactory” was a town-center landmark that employed a significant number of townspeople. He left many traces in the written records of the era, some of which gave contradictory impressions of who he was as a person. We set out to learn more about him. Early Life John Fletcher was born in Acton to James (a young Revolutionary War soldier) and Lydia (White) Fletcher on July 21, 1790. In Acton’s vital records, we found siblings Betsy (b.1786), James (b. 1788), Daniel (1797-1799), Lydia (b. 1800), and several who died young and whose names were not recorded. James (the father) was involved in the business of Acton and donated a piece of his land in 1806 to be part of the Town Common. The family first lived on what is now Hammond Street but then moved to a farm near the first meeting house (off of Nagog Hill Road near what was then the Brooks Tavern). John’s son, (Rev. James), later wrote about their home site, “Here stood for many years, from 1794 on, the Fletcher homestead, where James Fletcher, the father of Deacon John Fletcher, and his brother James and Betsey, the sister, lived during childhood up to the years of maturity. A few feet from this ancient cellar hole to the west is the site of the first Fletcher russet apple-tree. Childhood’s memories easily recall the ancient unpainted cottage, the quaint old chimney with the brick-oven on the side, and the fire-place large enough for the burning of logs of size and length, and in front to the southeast a vegetable garden unmatched at the time for its culture and richness, and a large chestnut-tree to the south, planted by Deacon John, in early life.” (Acton in History, p. 247) Though records of John Fletcher’s youth are hard to come by, we do have a physical description (from much later military pension records) that he had fair skin, black hair, and brown eyes. He no doubt attended the school nearby and would have helped on his father’s farm. As he got older, records show that he and his brother James Jr. served in the local militia. In April, 1808, John was already serving as a corporal in Capt. Simon Hosmer’s Company that became known as the Davis Blues. In 1810, John was chosen to be sergeant, and in 1813, he became the company clerk. By that time the country was at war. When the governor of Massachusetts called for troops to defend Boston in the fall of 1814, John Fletcher served as sergeant and clerk of what was by then Capt. Silas Jones’ Company. Brother James Fletcher was a corporal. According to Fletcher’s History, (p. 277-278) the company was first to report to headquarters and met with an enthusiastic reception as it marched through the streets of Boston. The British never attacked, however, and the company saw no action. The War of 1812 concluded soon thereafter. John continued to serve in the militia and eventually was made captain. Town meeting records refer to him as Captain John Fletcher in the years 1821 and 1822. In June 1812, John’s brother James was initiated into the Masonic Lodge in Concord, and John followed in June 1813. Both men were proposed for membership by Simon Hosmer. In 1814, father James and James Jr. bought a farm from neighbor Paul Brooks, including a house, barn and cooper shop. Presumably, the intention was to expand the father’s farming operation and/or to establish James on a farm of his own. Unfortunately, James Sr. died on Dec. 9, 1815 by the falling of a tree (according to his tombstone and Fletcher’s History, p. 246), an event that must have shocked and greatly changed life for the family. By 1814, we know that John Fletcher was already in the shoe business, as he listed his occupation as shoemaker when called up to serve in the War. In 1815, the town of Acton paid him $4.67 for providing shoes for the poor. We have not yet discovered details of the early years of his shoe enterprise, such as how he learned the trade, his sources of materials, and when he started hiring outside labor. In March 1819, James Fletcher Jr. sold to his brother John for $250 a half of his share of the land he held, including his father’s two farms, a woodlot, and “all other lots of every kind which I am now in posion [possession] of”. The records of the brothers’ buying, borrowing, and selling of property are voluminous and hard to pin down completely, but the impression one gets is that John managed to pay off his debts but James may have had more trouble and needed cash infusions at times. John and his brother James established a store together. Its exact beginnings are a little unclear from the records, but it was definitely operating before 1822 and probably by 1820 when James Fletcher’s census listing included two household members engaged in commerce. According to John’s son Rev. James Fletcher’s History (p. 272), the brothers’ first store was on the site of the present-day Memorial Library. We found from a deed dated Sept. 28, 1820 that James and John Fletcher, traders, bought a store near the meetinghouse from Francis Tuttle for $325. It was apparently quitclaimed by Widow Dorothy Jones on Dec. 7, 1821. (Land Records, Vol. 308, p. 232 & 233) In January 1822, Worcester’s Massachusetts Spy ran an ad offering a reward to be paid by James and John Fletcher to help track down the criminal(s) who, on the morning of January 22, burned their store “after having been robbed (as is supposed) of its contents.” The brothers would pay $100 for “the detection of the Incendiary or Incendiaries, and the recovery of the Property -- or $50 for either.” (Jan. 30, 1822, p. 4) Surette’s History of Corinthian Lodge noted that on Feb. 4, 1822, “Bros. John & James Fletcher, of Acton, having met with a severe loss by fire, requested assistance from the Lodge, and a subscription paper was opened and signed by the members present.” (p. 128) Fletcher’s History says specifically that the store was on the library site when it “was burnt.”(p. 267) At some point, perhaps after the fire, the brothers’ retail operation apparently was relocated to the southern end of the Common. (Fletcher’s History, p. 272, Horace Tuttle’s 1890 map of Acton, Caleb Butler’s 1838 Plan of the Common in Acton). John had bought from Theodore and Hannah Reed a piece of land and store south of the meetinghouse in late November 1817 that was probably the brothers’ store’s second location. The type of items sold can be glimpsed from James’ 1831 probate’s inventory that showed “Store Goods” including fabric and sewing supplies, quills, paper and “inkpowder,” school books and slates, hardware and tools, pairs of bellows, whips, combs for people and horses, household items such as lamps, dishes, pots and pans, pails, brooms, clothespins, window glass, and tin reflectors, food items such as spices, tea, molasses, and a “Lot of Mackerell,” and cigars, snuff, tobacco, corkscrews, taps, and alcohol (more on that later). After an engagement of six years, on April 25, 1822, John Fletcher married Clarissa Jones, daughter of Aaron Jones and Abigail Billings. (Clarissa’s brother Silas was Captain of John’s militia company during his War of 1812 service, and her sister Dorothy had quitclaimed the store a few months earlier.) The pair had waited to get married while Clarissa took care of her father’s household and boarding house in place of her incapacitated mother. (Acton Patriot, Feb. 13, 1875, p. 1) John and Clarissa’s children were James (b. 1823), Clarissa Jones (1825-1826), John Jr. (b. 1827), Edwin (b. 1829), Clarissa Jones (1831-1845), Abigail Billings (b. 1834), and Quincy Addison (b. 1846). John’s brother James Fletcher had married Louisa Robbins in 1819 and their only child Sarah Louise was born in March 1825. Louisa died in 1827, and James married Hannah Reed the following year. We do not know where the brothers’ widowed mother Lydia lived during the 1820s. She died on Dec. 29, 1828. According to Acton in History (p. 292), in 1828, John and his brother James built “the homestead” overlooking the Common on the site that later became the home of the Memorial Library. (Sixty years later, the house and barn were moved to Nagog Hill Road to make room for the library.) Apparently, the brothers and their families lived together. John Fletcher was moving up in social stature. By 1822, he was already referred to in land records as a “gentleman,” as opposed to a “yeoman,” a label given to his brother James as well as his father in earlier days. John and James both held town offices during the 1820s. John served in roles such as Sealer of Weights and Measures, Surveyor of Wood, and occasionally in other roles such as Highway Surveyor, Constable, or member of the School Committee. James spent several years on the School Committee, kept the town pound (at the northern end of the Common near the family farm), and served occasionally in other positions such as Hog Reeve. In addition to, and probably in conjunction with, their business ventures, the brothers were very busy in land dealings mostly around Acton center in the 1820s. They both borrowed and lent money. Money-lending seems to have been a much more neighborly affair in those days. Not everyone paid them back; one wonders what neighborhood relationships were like after the lender went to court to recoup his investment. Change, and a Nasty Rumor The early 1800s were a time of great change in which the old patterns of social cohesiveness were giving way. Increasingly, societal ills were blamed on alcohol consumption. John and James Fletcher were in the middle of that transition. Their business sold liquor. Rum, brandy, and wine were listed in James’ 1831 probate inventory, and John wrote in 1873 that he had formerly kept a “grogshop like other Rum sellers under licence.” Town records mention that in 1827 the highway taxes of the “Fletcher Tavern” could be partially paid off through work instead of cash. Unfortunately, the easy access to alcohol affected the brothers’ lives. According to a published letter by Horace Hosmer, both John and his brother James were excessively heavy drinkers. (Remembrances of Concord and the Thoreaus, Letters of Horace Hosmer to S. A. Jones, p. 54) The timing and the circumstances are not clear from the records, but at some point, John turned his life around. He gave up drinking, joined the temperance movement, and started speaking out at temperance meetings, sometimes in front of a large crowd. He was frank about his experiences. John was appointed to a nominating committee of the Middlesex County Temperance Society in 1839. (Christian Freeman and Family Visiter [sic] June 14, 1839, p. 3) Temperance views were not popular with everyone, and John Fletcher apparently rubbed some people the wrong way. People found ways to get even. Rumors flew that after his brother James died in 1831, John took James’ money and left his widow poor. Since that rumor found its way into the published book of Horace Hosmer’s letters (p. 54), we checked into whether there was any basis to it. James Fletcher’s probate file (Middlesex County file #7859) showed that the administrator of his estate was Francis Tuttle, Justice of the Peace, a prominent man in Acton who held many roles of trust. It is very unlikely that he would have been complicit in cheating a widow. John Fletcher did help to take the estate inventory along with Silas Jones and Joseph W. Tuttle. The inventory was extensive and meticulous, including household goods, store inventory, and items that were probably used in the business, such as a showcase. (The document did not mention a partnership. Unless James by that point was running the store on his own, presumably the store’s inventory was halved in the listing.) From land records, we know that James had bought, sold and borrowed against properties quite a bit. However, at the time of James’ death, despite his years of land dealings, his only real estate holdings were from a purchase that he made from John in 1829. Unfortunately, his debts exceeded his assets. In such cases, the laws of the time were not generous to widows. James’ widow Hannah was granted an allowance of $150 and her dower right of a third of real estate, but the creditors had to be paid. James Fletcher’s belongings were auctioned off. The probate record shows in detail who bought items and for how much. John Fletcher was only owed a small amount and bought a few items from the estate. However, he did buy James Fletcher’s share of their “homestead.” The deed, dated Dec. 22, 1832, was for an eighth of an acre of land east of and near the Meetinghouse with about two thirds of a dwelling house, a barn and a woodhouse, excluding the portion that had been "set off to the widow Hannah Fletcher as her dower or third in said Estate.” (Land Records, Middlesex County, v. 320, p. 32) The “set off” in James’ probate record shows that Hannah had been granted the “East part of the homestead.” Hannah’s share of the land started at the Common, went only 5.5 feet to the house and then went through the house to a stake and stones in the back garden, extended east 31.5 feet to property of the next-door neighbor, and then back to the Common. Hannah’s portion of the house included the “East room Bed room East chamber,” the east half of the cellar, and the east half of the garret. She also had privileges, such as going up the front stairs to her chamber, going to the well and to the woodhouse, entering and exiting the cellar via the bulkhead, and using the back kitchen, the oven, the “back house,” and the northeast corner of the wood house, eleven feet four inches by four feet nine and a half inches. The court valued her share at $425. John and James Fletcher seem to have been exceptionally close, living and working together. It seems highly unlikely that John would have deliberately impoverished his brother’s wife. (According to probate records, James’ daughter Sarah Louise went to live with her grandparents John and Sarah Robbins, so she was well-provided for.) Land records show that Hannah did not actually end up destitute; in addition to cash received from the estate, she had title to Acton pasture land that she sold in 1835. We found nothing to indicate that the rumor mentioned in Horace Hosmer’s letter was true. It seems much more likely that the accusation was the work of townspeople either jealous of John’s success or resentful of his temperance work, or both. In addition, we found other items that shed light on the relationship between John Fletcher and his widowed sister-in-law. Hannah remarried on April 11, 1844 to Almon Wright. According to Acton’s town records, the place of marriage was “at John Fletchers.” In fact, the census of 1865 showed that Almon and Hannah, by that time in their sixties, were living in the Fletcher homestead with John Fletcher’s family. Hannah presumably kept her dower rights to the homestead, but the arrangement hardly sounds as if the in-laws were estranged.  Real Contention In the 1830s to the 1850s, the temperance movement gained momentum and support. In Acton, there are references in town meeting proceedings to various attempts to make or enforce liquor laws. The agitation against alcohol was not appreciated by all. John Fletcher seems to have been in the fray and caught the backlash. In 1843 someone girdled a large number of his apple trees, an act that would kill them. The act was attributed to the fact that John was a “prominent Temperance man.” (Newburyport Herald, Oct. 26, 1843, p. 2) At the town meeting held on November 13, 1843, Acton townspeople voted to offer a reward of $50 for the conviction of the person(s) responsible. John Fletcher offered an additional $50 reward. We have found no indication that the rewards were ever paid. Temperance agitation continued. For example, in April 1844, the town debated choosing “a Committee to Complain of each & every person who violates the licence laws in this Town” and considered regulating “the sale of spiritous Liqours.” (The town voted to dismiss those proposals.) At the state level, Massachusetts passed a “prohibitory law” in 1852. John Fletcher was one of those chosen to be on a Vigilance Committee to enforce it. Neither the law nor the committee seems to have been popular. John Fletcher wrote to the Christian Watchman, “The Vigilance Committee for the town of Acton have made an effort to enforce the anti-liquor law, and a part of the result is, that I had a valuable orchard girdled last Monday night, and there were six bottles of vitrol [probably vitriol, diluted sulfuric acid] thrown through the window into Frank Snow’s parlor who is an active member of said committee.” (Aug. 18, 1853, p. 3) The Boston Herald reported on the same incidents but heartlessly added, “The attempt to enforce an unpalatable law is usually attended by unpleasant consequences.” (Aug. 10, 1853, p.4) John Fletcher also supported the movement to end slavery, at least as far back as late 1838, when he was a member of an anti-slavery convention in Concord. (Liberator, Dec. 28, 1838, p. “206”) That was just before the Middlesex County Anti-Slavery Society split over the issue of the right of women to vote on Society matters. A number of men walked out of an Acton meeting in July 1839 to form their own group. John Fletcher followed his minister Rev. James T. Woodbury out of the meeting. (See our blog post to learn more about that schism.) John, by that time, was an active member of the Evangelical Society that had broken away from the first parish church in town. He and his wife joined the new church in 1833, and John was named a Deacon of the church in 1838, a sign of standing in the community. (Later town records often refer to him as “Deacon Fletcher” to distinguish him from his son John Jr.) His wife Clarissa sang in the choir, for 25 years as the leading treble singer, and taught Sunday School classes. (Acton Patriot, Feb. 13, 1875, p.1) John also supported the church financially. According to the Boston Recorder of July 30, 1846, when the new meetinghouse was being erected for the growing congregation, one of the donations was “gratuitous blasting and clearing away a very bad ledge of rocks... by a company of young gentlemen from Dea. John Fletcher’s boot and shoe establishment.” (p. “122”) John remained a deacon and one of the church’s principal supporters for the rest of his life. In 1840, John Fletcher was appointed to a committee to plant trees on the Common. Apparently, it was the year of a bad drought, and it was through his efforts and those of Francis Tuttle that the young elms and other new trees survived. Those shade trees were a beloved feature of the Common for many years. (Fletcher’s History, p. 292) During the politically tumultuous 1840s and 1850s, John Fletcher was affiliated with political parties dedicated to ending slavery (among them, the Free Soil and Liberty parties). He ran for offices several times and was selected as a Middlesex County Special Commissioner for several years. As a Free Soiler, John Fletcher was chosen to serve as postmaster, a political appointment, in 1853. He served until 1855 when an anonymous letter to the Boston Herald mentioned that the post office was moving from a “shoe shop” to the public room of a small country hotel where the postmaster was a “true Democrat.” (July 25, 1855, p. 2) Back to Business Meanwhile, the shoe manufacturing business seems to have thrived. Fletcher’s factory was at the south end of the Common that stood in front of the location of today’s fire station, (7 Concord Road, but it was at least in part where the road is today). It was near a store, tailor shop, and hotel. We have not yet found an exact date for that building, even in his son James’ writeup of the business: “Finding a ready sale for his goods, he continued to enlarge his manufacturing facilities until his boots and shoes were well and creditably known far and wide.... He was conscientious in his dealings with his patrons, stamped his name upon his work, and made it good, if at any time there was a failure.” (Fletcher’s History, p. 268, 292). The 1850 manufacturing census shows that John Fletcher’s boot and shoe business was the major employer in town. Some of the employment was undoubtedly piece-work done at home; monthly wages were $1,000 for 35 men and $50 for 20 women. The annual output was 5,525 pairs of boots (worth $12,000) and 15,000 pairs of shoes (worth $15,000). According to memoirs and John Jr.’s obituary in our archives, the firm became John Fletcher & Sons during the early- to mid-1850s when John Jr. and Edwin were brought into the business. John Sr. continued to supervise the operation. John Jr. apparently visited general stores in the area to promote their products. (The contacts he made in his travels were useful in other ways; he was later elected to the state legislature and the state senate.) Edwin supervised the cutting part of the operation and served as general foreman. Much-younger brother Quincy at some point served the business as a handyman. In 1860, Fletcher & Sons employed forty men, producing around $40,000 of boots and men’s shoes. The footwear was still made individually (as opposed to by mass production). Most stitching was apparently done by hand, but the business had acquired three sewing machines at that point. Business slowed with the beginning of the Civil War. A letter in the Society’s collection from John Fletcher Jr. to Captain Daniel Tuttle mentioned the that business failures were common at that time and that John Fletcher & Sons was feeling the effects: “Most of our hands are laying off,” and “we are not doing much of anything and should rather stop entirely.” (May 26, 1861) Fortunately, the business survived. In 1862, a fire in the center of Acton changed its look permanently. It was evidently believed to have been an act of arson. (Fletcher’s History, p. 269) According to a letter in the Society’s collection, (John Hapgood, Oct. 26, 1862, original spellings retained): “On Friday evening last one of the most distructive fires broke out that ever hapened in Acton Cause as yet unknown. It origenated in the stable in the rear of Capt John Fletchers shoe Manufacturory burning that and the store adjoining and the Tavern or boarding house and communicated to the Town-house all in a short time lay in ruins. The wind at the time was vary high and things all vary dry there was but vary little water in the wells. some of them none... I went as soon as I knew of it after 8 O,clok but they were all on fire before I could get there Some of them consumed. The Enjines came up from Concord but did not arrive untill 10 O,clock to late to do much good.” It was a devastating fire, destroying the factory, barn, hotel and, via a wind-driven shingle, the “town house,” as the town’s 1806 meeting house was by then known. One can only imagine the impact of that night on the Fletcher family, watching the factory burn and fearing that the fire might spread to their own houses, including John’s home next to the town house. According to his son’s History, John Fletcher’s response, though he was over seventy at that point, was to rebuild his factory and to encourage the town to rebuild its town hall. (p. 292) The new Fletcher factory had three floors and was built in the Italianate style similar to the new town hall, with a porch, cupola, and flagpole at the top. By rebuilding, John Fletcher not only continued the family firm and spearheaded the rebuilding of the village, but also maintained employment for many of his neighbors. The 1865 state census listed occupations of nearby residents, including “shoemaker,” “bootmaker,” “shoe binder,” “boot stitcher” and “machine stitcher.” (The shoe and boot makers were all men, the “stitcher” titles were given to women.) According to a memoir by O. D. Wood in the Society’s collection, most of the farm houses in Acton Centre had “tenements” (apartments) that were rented out to shoe makers’ families. Shopkeepers and others would also have been affected if the village’s main employer had shut down. The 1872 Acton town valuation shows that John Fletcher & Sons were taxed for “stock in trade” worth $6,000 and one horse. John Fletcher himself was assessed for $2,000 “money” plus the shoe manufactory ($3,750), houses (at least 4, worth $2,500), two barns ($550), a shoe shop ($50), a Hill orchard ($200), and various pieces of land ($745). O. D. Wood’s memoir talks about John Fletcher & Sons’ business around that time: “They made several kinds of boots, one kind of rugged boot called ‘cow hides’ and if well greased would shed water quite well. These were worn by farmers for such work as ploughing. The other kind were of finer leather and more of a dress boot. A farmer who had the two kinds called the best ones the handsome pair. Nearly all men in those days wore boots of some kind. They also made some ladies shoes.” Looking Backward and Looking Forward

Age does not seem to have slowed John Fletcher down much. As far as we know, he continued to supervise his business. He stayed firm in his temperance beliefs. In July, 1869, he was one of the leaders of a temperance organization whose celebration attracted thousands to Walden Pond. (American Traveller, July 10, 1869, p. 2) He was still writing letters in support of temperance in 1874, mentioning that “in the early days of Acton even the minister considered 20 gallons of rum highly acceptable in lieu of a portion of his salary,” an era referred to as “semi-barbarous days.” (Springfield Republican, Feb. 3, 1874, p. 3) Deacon Fletcher was not one to mince words. John Fletcher’s life changed, however, in February, 1875. His wife Clarissa died after a two-week bout of pneumonia. She and John had been married more than fifty years. John told the Acton Patriot that “In our active life we had so much to do that we never found time to quarrel,” and that if he’d had any success in business, it was because of his wife’s “earnest co-operation.” In addition to being the mother of seven children, “for twenty-five years, with the help of a girl, she enabled her husband to give all his workmen a home in his own family, at the low price of eight shillings per week for their board.” She was remembered as a “woman of large heart.” (Feb. 13, 1875, p1) John Fletcher died July 16, 1879, just short of his 89th birthday. The business was shut down soon thereafter. He had been the oldest citizen in town and had an undeniable impact on Acton’s history. He possessed unusual business acumen and drive, had strong convictions and the determination to act on them, and did not shy away from a confrontation. He made enemies. But he also cared about the important social issues of his day and was willing to change his mind, to admit his own weaknesses and mistakes, and to take unpopular stands. Toward the end of his life, he felt compelled to write a remarkable letter to William Lloyd Garrison. In the 1873 letter, John Fletcher acknowledged that when the anti-slavery advocates in Acton split over the question of women’s rights, he had chosen to join Reverend Woodbury’s camp. In retrospect, however, he regretted that decision. He wrote, “you was right on that question and I was wrong. and our Ballot Box has become so corrupted that it seems that we do more than ever need the female vote to save the nation from destruction.” Even in his ninth decade, John Fletcher was still pondering important issues, growing, and speaking out for what he believed to be right. Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed