|

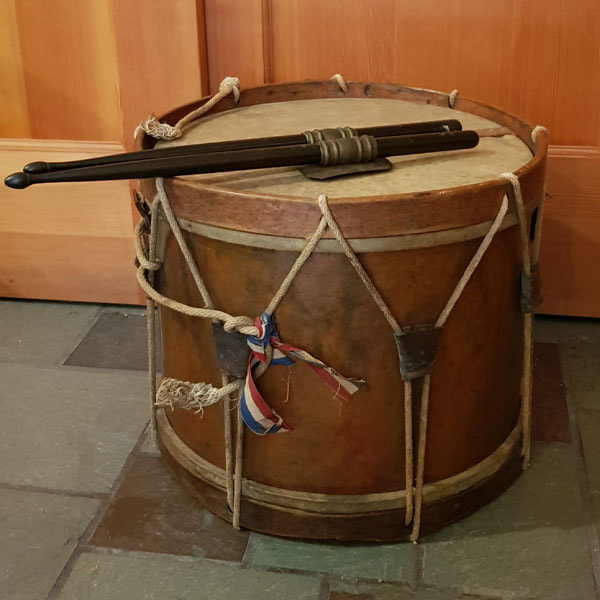

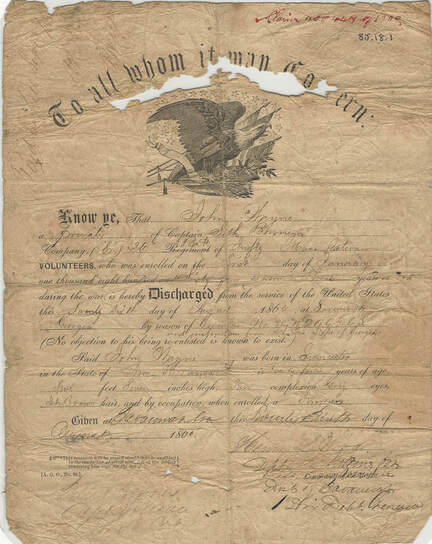

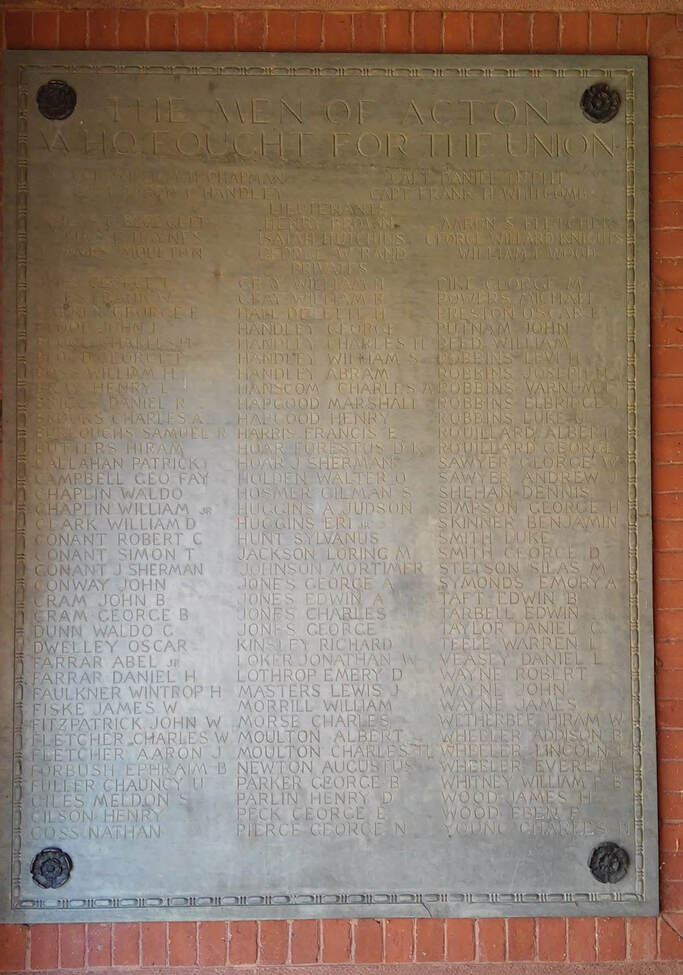

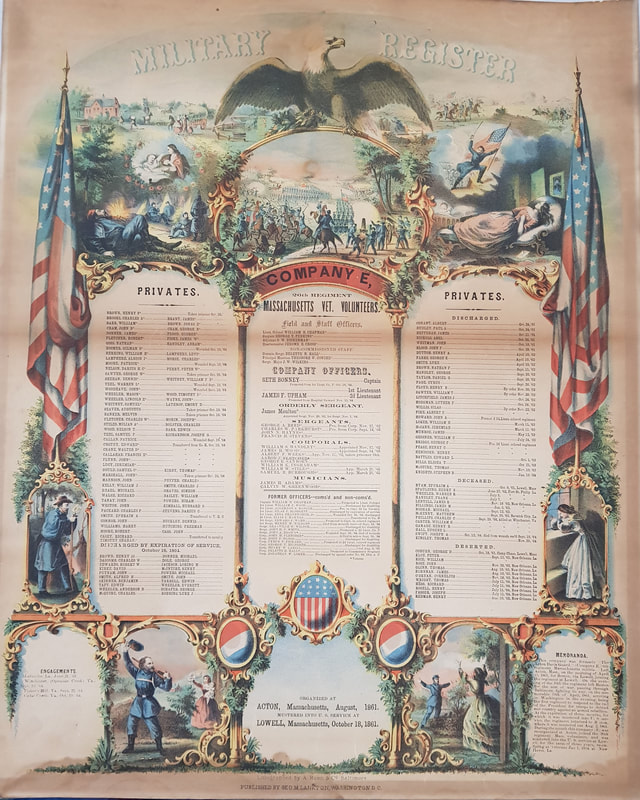

5/2/2022 The Good Idea That Split a Town Soldier suggested to be Samuel Burroughs, Co. E, 26th Reg. Soldier suggested to be Samuel Burroughs, Co. E, 26th Reg. In our previous blog post about the postmaster controversy in 1880s South Acton, we mentioned that one of the underlying factors was probably resentment and distrust related to an ongoing dispute over the payment of bounties to some of Acton’s Civil War veterans. Despite repeated attempts by Acton’s townspeople to pay them, the veterans had never received the money. In 1882, Massachusetts enacted a law (Act of 1882, Chapter 93) that would have authorized the town to make the payment, but a lawsuit by a few influential (and high-income) taxpayers had sought to block it. The course of the controversy was somewhat complicated, but in the long run, to many Actonians, the issue became about more than money. Resentment festered and found outlets in a number of other disputes in the 1880s. The Background Acton sent several companies to the Civil War. The first, Company E, 6th Regiment, went out immediately upon Lincoln’s call for three-month volunteers in April 1861. After the men returned from their service around Baltimore, a company with a three-year enlistment was formed. Company E of the 26th Massachusetts Regiment was organized at Acton in August 1861 and was mustered into service in Lowell on Oct. 18. They were sent first to Ship Island in the Gulf of Mexico and then to Louisiana. Another company went out in August 1862 -May 1863, serving in Virginia, and a 100-day company served July-Oct. 1864 around Washington and on prison-guard duty on an island in Delaware Bay. Both of the latter companies were known as Company E, 6th Regiment. As in previous wars, it was important to the town that it supply soldiers to the cause. Towns were expected to fill a quota based upon population. If they could not fill their quota, they were threatened with a draft. Early in the war, patriotism and idealism were enough to get men to enlist. As the years wore on and the toll of war became more obvious, towns, states, and the federal government started offering financial incentives to induce men to join up. Known as bounties, the payments differed from place to place and over time. Not surprisingly, these disparities caused trouble. A federal bounty of $100 had been offered since early in the war, but it was deferred until the soldier was discharged (honorably). The Militia Act of 1862 required the states to institute a draft if they could not meet their enlistment quotas. In March 1863, Congress passed the Enrollment Act, authorizing a draft system, specifying that all able-bodied male citizens and immigrants who were applying to be citizens from 20 to 45 years of age would, if called, have to serve. Married men 35-45 would be drafted later than the others, and there were a number of exemption categories, mostly on the basis of the needs of family members. Most controversially, people could pay for a substitute to go or, if a substitute was not available, pay $300 to the Secretary of War for one to be found. The Enrollment Act and the ensuing Draft Riots in New York City that summer had pointed to the urgency of getting and keeping men in the ranks. On October 17, 1863, Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 300,000 additional troops, to be raised by the states according to their quotas. Enlistments would be “deducted from the quotas established for the next draft” which, if a state did not make its quota, would begin on the 5th day of January, 1864. The Secretary of War upped the federal bounty, with a premium paid to reenlisting veterans. Meanwhile, Massachusetts was doing its best to fill its overall quota, and its towns were doing the same, offering bounties for enlistment or re-enlistment. Though originally the intention of the bounties was to support a town’s own soldiers, there was certainly an incentive to fill the town’s quota with any soldiers, wherever they could be found. There were some unintended consequences of the system, however. Unscrupulous recruits would sign up, claim a bounty, and never report to camp. These “bounty jumpers” might then sign up elsewhere, possibly under an assumed name, to get another bounty. Other frauds were to sign up and collect a bounty even though the recruit knew that he would eventually be rejected from serving (because of a disability or signing up underage, for example). A more basic problem with the system was that towns that could afford to pay large bounties were more likely to fill up their quotas than towns in greater financial difficulty. Disparities of bounties and the substitute exception yielded the impression that the rich were able to avoid the worst consequences of the war while the poor fought. Some of those who hired the substitutes, considering it a financial transaction, felt that they had the right to be reimbursed for their substitute payment. Some were of the opinion that those who went as substitutes, because they were paid to go in place of a drafted man, did not deserve the bounty for going to war. The divide between the poor, whom some judged for enlisting for the money offered, and the rich, who could afford to pay for a substitute, grew. There is no doubt that some bitterness that festered in Acton after the war was due to this economic divide. To try to introduce more equity into the system and to deal with some of the bounty-jumping problems, Massachusetts’ legislature passed a number of laws. In fairness to all parties in Acton’s bounty dispute, even with the benefit today of being able to read the digitized laws of the Commonwealth, the bounty laws make confusing reading. It must have been quite hard to keep up with them in the early 1860s, during a war, and especially in places with poor communication. Practice did not necessarily follow the intentions of the lawmakers. One of those intentions seems to have been that local bounties would stop, although towns seem to have interpreted the laws as limiting local bounties, not eliminating them (See Chapter 91, approved March 1863). A law passed in a special session in November 1863 (Chapter 254), set a uniform Massachusetts bounty at $325 for those who enlisted for three years. Though well-intentioned, the new law did not solve the problems. Rightly or wrongly, a number of towns’ representatives continued promising what they believed to be the maximum local bounty allowed at the time for the reenlistment of serving soldiers, $125. Acton’s Veterans Reenlist Acton’s bounty controversy centered on the soldiers of the 26th Regiment who had been sent to Louisiana in 1861 and served there through the beginning of 1864. During the company’s early service, the most harm came to the soldiers through disease. In June, 1863, the Regiment saw action at LaFourche Crossing and later made an attempt to take Sabine Pass. In the fall of 1863, it went to Opelousas and New Iberia, Louisiana. A November 27, 1863 letter from Delette Hall to his cousin Henry Hapgood (who had returned from the nine-month company sick) said: New Iberia is quite a villiage. About 50 miles from Breashear City on Bayou Teche River. This is quite a muddy place in wet weather We have to ditch the ground to keep from being drowned out Yesterday was Thanksgiving Day. but was not observed here except by issuing a ration of whiskey to the men. I thought of you all & if I was not there my mind was. I was on Picket & had a piece of salt pork & some hard tack for dinner. Well that was a little better than I had two years ago in Boston harbor. & next year I hope I shall be at home. We shall soon be nine months men our term expires the 18th Oct 186[4] which day we were mustered into the U. S. Service. It seems a long time to look ahead. I hope the rebs will get enough before the year is out. Clearly at that point, Delette Hall and his compatriots were not thinking of reenlisting. At the end of 1863, the Union army needed to keep seasoned men in its ranks. Experience showed that raw recruits were more likely to desert. The hope was that reenlisting soldiers would be inured to camp conditions, be willing to follow orders, and stay. Men who were acclimated to conditions in the South would have been considered an asset to the 26th Regiment. To understand what happened to spark the bounty dispute, we have to rely on testimony given much later. A two-sided supplement printed by the Acton Patriot laid out all that was said at a hearing before the Legislative Committee on Military Affairs, January 26, 1882 (in the Society’s collection and also transcribed by Brewster Conant). By the time one has read through the claims and counterclaims, one is hard-pressed to know what really happened. There were contradictions, inconsistencies over time, fading memories, and the influence of “circulars” and petitions on people’s interpretation of events (operating like the social media of the time). Also, by 1882, the needs of the war were long past, whereas the pinch of tax bills was a present problem. Though it is impossible to be completely sure of who knew what and when they knew it, most people in the post-war period seem to have agreed upon a few points. Acton’s Captain William H. Chapman, veteran of the 3-month original Acton Co. E, 6th Regiment and by late 1863 the Captain of Co. E, 26th Regiment, was also serving as the recruiting officer of the 26th Regiment. He was aware of the need for trained soldiers and of competition from other Massachusetts communities that he believed were offering local bounties to soldiers to re-enlist, with the quota credit going to those towns. Concerned that Acton would lose its soldiers to other towns offering financial incentives, Capt. Chapman told the men of the Acton company that Acton would “do as well by them as any other town” if they would reenlist to the credit of Acton. The going bounty rate at that point seems to have been $125. In later years, few disputed that the soldiers reenlisted in early 1864 in the 26th Regiment, for 3 years or the duration of the war, believing the promise that Acton would pay them a bounty of $125. Few disputed that Captain Chapman made the promise. The original dispute centered on whether or not he had been justified in making the promise and whether the town had the legal (or moral) obligation to keep it. Part of the problem with the later bounty dispute is that people were looking back many years and judging based upon subsequent events. At the time that Capt. Chapman was recruiting, the Regiment was in New Iberia, Louisiana. According to his later testimony, the mails were sporadic and it was not feasible to send messages to Acton by telegram. One can see how the captain might have felt that he needed to make decisions on the spot. Back home in Acton, however, there was a recruiting committee who felt that they should be the ones making decisions, particularly with respect to how the town’s money was spent. They also were more likely to have had a chance to read the laws passed by the legislature. The recruiting committee denied having authorized the bounties in advance and claims were made that no one knew about the bounty promise, but Luther Conant, longtime moderator, remembered that the issue was discussed at the 1864 town meeting. The war went on. After much of Company E reenlisted, the 26th Regiment was sent to Virginia where the company moved into action at Winchester (Opequon Creek) on Sept. 19, 1864, Fisher’s Hill on Sept. 22, and Cedar Creek on October 19. The company had lost a number of men to disease and also lost five men as a result of the fighting at Winchester, including Delette Hall's brother Eugene. Some were injured, including Captain Chapman, who managed to survive a gunshot wound to the head. The Company stayed around Winchester through May 1865. They spent a month in Washington, D. C., then were sent to Savannah. They were discharged in September 1865. Undoubtedly the men expected that when all was said and done, they would be paid their promised bounties. During the war, the town had paid some recruits bounties. The 38 members of the nine-month company recruited in the fall of 1862 received $100, with an additional $25 for the 23 recruits “called for from this town on the first quota” who signed up for three years. The town voted in December of that year that if it were required to supply more men, the recruiting committee was authorized to offer the same bounty to any who enlisted or were drafted. The 1862-1863 town report listed every man in service and whether or not he had received a bounty payment from the town. (The state seems to have retroactively reimbursed the $100 bounties paid to the 1862 recruits.) In November 1863, the town voted that the Selectmen plus three additional Recruiting Committee members would have discretionary powers regarding bounties. In November 1864, the town voted that their recruiting committee should investigate the claims of the town’s serving soldiers and those who had returned home and that the town should raise $5,500 to recruit men for the war. Given all of that, it does not sound unreasonable for Capt. Chapman to have thought that the town would back his claim that the town would do as well by its men as other towns were doing. However, the war ended, (most of) the veterans came home, and the claim had never been paid. The War’s Aftermath At the March 1866 town meeting, Acton debated paying those soldiers who enlisted in 1861 and reenlisted in 1864 the same bounty that had been paid to soldiers who enlisted later and served in the US service for less time. The town decided to postpone any action until the state and federal governments had taken action on bounties. According to Phalen’s history of Acton, “As things later developed this proved to be an unwise decision but at that time nobody could have foreseen that by this action the town planted the seeds for its most vicious and prolonged local battle.” (p. 197) Though this fact was not usually mentioned in the Acton fight, bounty claims took up a great deal of energy on the part of both state and national committees in the post-war years. The Massachusetts Legislature’s Committee on Military Affairs dealt with petitions of many towns, including petitions from Acton in three different sessions. Acton voted to pay soldiers’ back bounties in 1872 and petitioned to be able to pay it. In early 1881, the Committee heard petitions, not only from Acton, but also from Wilmington, Stoneham, East Bridgewater, Andover, and Natick, all rejected. Acton’s petition went nowhere until the third time it was presented in early 1882. In March 1882, the House passed a bill that would allow Acton to raise up to $4,000 to pay $125 to each of the veterans who had reenlisted in the 26th Regiment under the call of the president dated Oct. 17, 1863, were credited to Acton, and were never paid. The bounty could be paid to the soldier’s heirs if he had died. In response, at town meeting on April 3 1882, the town of Acton voted to pay the bounties, but the measure passed by only four votes (219 to 215). By this point, the controversy had split the town down the middle, apparently even at town meeting where Phalen wrote that “The glowering partisans congregated on either side of the center aisle.” (p. 231) Town meeting records mention that “it was voted to have the area in front and on each side of the Desk kept clear so that voters need not be obstructed in approaching the Polls.” Whether this was because of hostility or because it was Acton’s largest town meeting ever is not clear. After the vote, a cannon was shot off in South Acton in celebration (Acton Patriot, Apr. 6, 1882, p. 1) However, as often happened in Acton politics, a vote taken was not seen as final, but only as an opportunity to reconsider. Two town meetings followed. Both sides undoubtedly tried to sway opinions and get out the vote. The Acton Patriot’s Concord Junction reporter mentioned on Sept. 7, 1882 that “Thomas Clifford was earnestly sought for early Saturday morning by one of Acton’s heavy taxpayers. His object was to secure his vote against paying the soldiers’ bounty.” Probably the same heavy taxpayer “offered to bet $100 with any live men that the soldiers get beat.” (page 1) These efforts did not change the outcome, however. On August 21, an attempt to overturn the vote failed by 204 to 194, and on Sept. 2, the anti-bounty side lost again by 206 to 198. Phalen’s history of the town of Acton seems to indicate that the resolution of the bounty issue happened in 1882 with the Senate and House overriding the governor’s veto. “Thus ended the great bounty fight beside which all other Acton rows seem rather tame. The payments were made with reasonable promptness with one exception...” (p. 233). Searching Acton’s town reports did not yield a record of those payments; in fact, the bounty tax seems to have been assessed, held onto, and then without explanation refunded by the town. The reason was legal wrangling that went on much longer than is mentioned by Phalen. Not able to swing the vote in their favor, the opponents served an injunction on the town to prevent payment and hired Judge E. Rockwood Hoar as their counsel. According to newspapers of the time and legal synopses, the opposition’s case made its way through the legal system and was heard by the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts in early 1885. The case hinged on the constitutionality of the 1882 act of the Legislature (chapter 93) that authorized the town to raise taxes to pay the bounties. According to the Supreme Judicial Court’s ruling, the town of Acton never promised to pay a bounty, did not (directly) receive the men’s services as soldiers, and was not responsible for paying them compensation. Therefore, it had no debt to them. Any payment made so long after the fact would be akin to a gift of gratitude to private individuals rather than payment of a debt for a public purpose (as inducing enlistments would have been). Taxes must serve a public, not private, purpose, and therefore, the 1882 law allowing Acton to raise taxes to pay the veterans of the 26th Regiment was unconstitutional. The bounty opponents must have thought that the matter would end there, but the dispute had gone too far by that time. By March, 1887, the town of Acton was petitioning the state to pay the bounties, because Acton was barred from raising the money itself. (Boston Journal, March 11, 1887, p. 1) Both sides testified again. The Society owns a copy of the opposition’s testimony that started with the statement that they were aware that they were “opposing the claim of the men, who, in a critical time in our history, rendered with such distinguished services to the country that it seems almost like robbery, - unpatriotic at least, to withhold from them anything in the way of pensions or gratuities that they may demand.” The opponents followed up, however, by saying that the Commonwealth owed the men nothing because this was a town matter. (Of course, the town previously had been kept from paying the claim by this group’s lawsuit.) The testimony ended with “We would respectfully ask, therefore, that you, as guardians of the public treasury against unfounded claims” would find against the town of Acton. The Society also owns a copy of the proponents’ testimony. The testimony mostly reiterated points made before, although it does contain a paragraph of personal attack on the opponents; the sides were portrayed as humble veterans versus the rich. At any rate, the Senate Committee on Claims reported favorably on the town’s petition. (Boston Journal, April 15, 1887, p. 3) In May, the Committee on the Judiciary ruled that the Legislature has the right to appropriate and pay money to individuals, even if it could be portrayed as a gratuity, if there were “some equitable ground upon which such payment ought to be paid.” (Boston Journal, May 5, 1887, p. 2) The legislative debate on the measure was reported in June, 1887. Some cited fear of opening the floodgates to other, similar claims. However, the majority, including Mr. Conant of Acton, felt that the resolve was an “act of justice.” (Boston Journal, June 8, 1887) Finally, the joint Resolve of 1887, Chapter 106 ordered that $125 was to be paid by the Commonwealth to the 31 soldiers (or their legal heirs) of the 26th Regiment who had reenlisted and never received the bounty they were expecting. The governor had objected to the Resolve, but the Senate and House of Representatives passed it over the Governor’s objections on June 16, 1887. The fight was finally over. The veterans got their bounties and apparently it was the people of Massachusetts as a whole who made good on the promise, rather than the people of Acton who had voted repeatedly to pay it. It is clear that a dispute allowed to fester for over 20 years was extremely harmful for the town. Putting off dealing with the problem in the hope that it would conveniently disappear led to infinitely more trouble later. As the bounty dispute dragged on, campaigns for support, including assumptions, exaggerations, and character slurs, led to increasing polarization. Both sides’ attitudes seem to have hardened into a belief that they were fighting for the “right.” Newspapers elsewhere noted Acton’s contentiousness with comments such as “Acton folks are still squabbling...” (Springfield Republican, Aug. 19, 1882, p. 6) What becomes most apparent is that the bounty dispute reflected divisions in society. On the one hand were those trying to prevent payment. They portrayed the veterans asking for bounties as greedy opportunists who had not received a legitimate (or perhaps any) promise of payment before they reenlisted and who were trying to take hard-earned tax money from Acton’s struggling farmers and from families of veterans who had not received a bounty. Those supporting the bounties believed that the town should make good on the promise. They portrayed the men against the bounties not as struggling farmers, but as rich taxpayers who were too stingy to pay the money that had been promised to men who risked their lives in the war. Underneath the accusations were basic issues, especially about who has the right to run the town. Should it be the influential, well-to-do men who had served (and controlled) the town for many years, or less-wealthy men who perhaps moved about looking for opportunity? The committee at home during the war had been either elected or appointed and felt they had the right and the duty to act for the town and decide how to spend its money. Those who were far away in the field at the time felt justified in recruiting for the town. The fact that there was some justification for both sides’ viewpoints made the divisions much more entrenched. As is often the case, after all of the conflict that was reported in the newspapers of the day, the actual resolution and payment of the bounties was apparently done without much fanfare. Though it is likely that the participants remembered the vitriol involved in the dispute, life moved on. Three years later, Acton had a Memorial Library honoring its veterans’ service. Acton’s veterans of the 26th Regiment (and of the bounty fight) were proudly listed at the entrance of the new Library. References:

Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed