C. L Heywood [43] C. L Heywood [43] Ann F. Heywood, subject of our last blog post on Acton’s first female voters, was married to Charles L. Heywood, owner of a South Acton mill. We had very little information about them to start, but our research revealed that they were celebrities by the standards of South Acton in the 1870s. Charles, as it turns out, was unusual by any standard. Ann evidently was herself worthy of note, but, as is frustratingly typical, she was much less documented in written records. The Early Years We do not know much about Charles and Ann's early lives. Records of that time are sparse, and neither Charles nor Ann grew up in Acton. We do know that Charles Lincoln Heywood was born to Lincoln Heywood and Rebecca Priest in Lunenburg, MA on April 17, 1828. The eighth child in the family, he grew up in Lunenburg and was educated in its local schools. His father was Deacon of the Unitarian Church. About the time that the Fitchburg Railroad came through Lunenburg (approximately 1845), Charles went to work for the line as a crossing tender. Charles was obviously a young man of ability; he moved up steadily in the railroad's ranks. By 1850, 22-year-old Charles was living in Fitchburg with the Israel Goodrich family and working as a Wood Agent for the railroad. In the 1855 Massachusetts census, he still had that title and was living in a "hotel" in Fitchburg. Within the next year or two, Charles was promoted to Roadmaster, a managerial position responsible for track conditions and safe operations. He continued to serve as Wood Agent as well, at least at first. Charles soon moved to Concord, MA, where he joined the Corinthian Lodge of Masons. He was a resident of Concord when he married Ann Tyler. [1] Ann Frances Tyler was born June 18, 1825 in Attleboro, MA, the fourth child of Samuel Tyler and Betsey Samson. Ann was only three when her mother died. According to a Tyler genealogy, her father was "an enterprising, influential man in Attleboro, and a pious church-member. His will mentions him as 'a depraved worm of the dust.'" It appears that Ann and Charles both grew up in homes in which religion was important, but beyond that, we do not know any more about their upbringing or how they managed to meet. They were married on November 25, 1857 either in Attleboro or in Providence, RI where Ann was living at the time. [2] A Busy Life The couple moved at some point to Belmont, MA where Charles was living when he registered for the draft in 1863 and where he became a charter member of the local Masonic lodge. In September 1864, after many years of service, Charles was promoted to the position of Superintendent of the Fitchburg Railroad. He would serve in that role for about fourteen years. [3] Charles seems to have possessed an unusually active mind and the energy to turn his thoughts into reality. Apparently, it was his idea to create the amusement park at Walden Pond in Concord that opened in 1866. Though Charles grew up in Lunenburg, his family roots went way back in Concord. His relatives seem to have owned a significant portion of the shoreline of Walden Pond, and the Fitchburg Railroad conveniently went right by. The railroad bought up land bordering the pond and cleared some of the woods to create an entertainment area with a large hall for use as a dancing pavilion or a gathering place for large meetings. Tables and seats were provided for picnicking, and for the more actively inclined, there were trails, swings, “teeters,” bathhouses for swimmers, and rowboats. People were delivered by train right to the park that was usually called some variant of “Lake Walden” or “Walden Pond Grove.” [4] Though to many today, Walden Pond should be kept as pristine as Thoreau saw it, at the time, many would have considered the park a societal benefit that allowed city dwellers a respite in fresh air and a beautiful spot. It was enormously successful. A Waltham Sentinel reporter, having recently enjoyed “a fine boat ride with several of the Fitchburg railroad officials, accompanied by their ladies; among the party Mr. Heywood, the Superintendent,” wrote that the park was “rapidly becoming quite popular.”[5] J. C. Moulton, “a well known Artist from Fitchburg” was there that day with his “machine” for making stereopticon views for sale, which would have been good to promote the park. The first season of the venture was summed up in the Nov. 30, 1866 Waltham Sentinel; the Fitchburg Railroad had brought out thirty different groups to the grounds, about 10,000 persons, without mishap. [6] The venture grew from there. By June 1869, large boats with side wheels and docks to accommodate them were added. During its first five years, newspapers reported that Walden hosted gatherings of veterans, temperance advocates, Masons, Good Templars, Sunday Schools, Spiritualists, and students and alumni of the New England Conservatory. In July 1869, the "Grand Temperance Celebration" featured speakers, music, dancing, boating, swinging, ball playing and a Velocipede rink. The special excursion admission and train fare from Acton was 50 cents. The third annual Musicians’ Picnic in 1870 drew more than 3,000 people to hear at least seven bands including Acton’s 19-piece band led by G. Wild. On July 4, 1870, the estimated crowds were 8,000-10000; the railroad used every serviceable car to accommodate them. In the early years of the 1870s, trains started bringing “the children of the poor” out from Boston to enjoy a day at the amusement park. [7] Walden was only one of Charles L. Heywood’s brainstorms. As Superintendent of the Fitchburg Railroad, he conceived numerous special excursions to provide people with recreation, edification, or simply a change. In addition to promoting events at Walden and closer to the city, the railroad carried people to West Townsend and environs to gather greenery, trailing arbutus, checkerberries and mosses with which to celebrate May Day. Excursions were arranged for people to see the engineering wonder of the Hoosac Tunnel. Superintendent Heywood invited the famous Rev. Henry Ward Beecher to preach at Lake Pleasant, a Spiritualist campground in Sept. 1875. Montague depot was nearby. [8]  Bridge Guard Bridge Guard Charles’ mind was also busy thinking of ways to make the railroads safer. In 1866-67, he was granted patents for a railroad snow plow and a “bridge guard” to keep brakemen from being knocked off the top of railroad cars as they worked. Charles’ plow, apparently “ingenious,” efficiently and thoroughly cleared the tracks. Adjustable “wings” could clear five feet on either side of the tracks and would retract if they hit an obstacle. His plow was used, at the least, by railroads in Massachusetts, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin. Charles’ “bridge guard” was “a light movable crane” that would give brakemen working on top of railroad cars warning before they were hit by the bridge.[9] It apparently was widely adopted, as it “proved a great protection against accidents.”[10] Charles may have traveled to promote his inventions. In addition to exhibiting at the 1865 Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association in Boston, he was also one of the exhibitors at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia.[11] Charles became known as a strong advocate for railway safety: “Even the ordinary signs at crossings he did not consider sufficient, and the reading on many of them he had so amended as to direct travelers to ‘look both ways’ before attempting to cross the tracks. There was no device brought to his attention that promised to reduce the chances of accidents which he did not forthwith adopt.” [12] Charles and Ann seem to have moved around. They may have stayed in residential hotels at times and may have had multiple properties at others, but they were always near the railroad. In May 1866, Charles bought a house on Main Street, near the corner of Auburn Street, in Charlestown, MA. He and Ann joined Harvard Church there in early 1868, and in May 1869, an ad appeared in the Boston Traveler “For Sale or To Be Let on a Long Lease – A good House, Stable, and 17,000 feet of land, well stocked with fruit and shade trees, near Waverly Station, Belmont, Mass. Inquire of C. L. Heywood, at Fitchburg Railroad, Superintendent’s Office.”[13] Charles transferred his Masonic membership to Charlestown in November, 1871. For some reason, we were not able to find Charles and Ann listed in the 1870 census; perhaps they were traveling at that time or staying at a summer location, possibly in South Acton. As far as we can tell, Ann and Charles had no children of their own. Around 1870, Ann’s niece, Eunice Tyler (Read) Crawford, daughter of Ann’s sister Eunice and wife of George Crawford, passed away. She left a child, Herbert Lincoln Crawford, who had been born in Pawtucket, RI in September 1868. Charles and Ann took him in. Whether or not the arrangement was meant to be temporary, it became permanent, and in 1878, while living in Belmont, the couple adopted the boy. His name was changed to Lincoln Crawford Heywood. Abundant Charity While still working for the railroad, Charles gave of his prodigious energy and his money to charities. He took special interest in the welfare of the inmates of the Charlestown state prison and taught Sunday school there. The Boston Daily Advertiser noted in January 1870 that he had given his students a book of their choice as a Christmas gift. He was also involved in the Massachusetts Society for Aiding Discharged Convicts. His belief in rehabilitation was obviously deeply held, because his kindness to prison inmates extended to the man who had killed Charles’ brother George. According to Cunningham’s History of Lunenburg, Charles met the prisoner responsible for his brother’s death, forgave him, and actually helped to get him pardoned. We were able to confirm the pardon but not Charles’ role in it. Cunningham was well acquainted with Charles’ father and apparently knew Charles, so presumably he heard the story from someone who knew what happened. [14] Prisoners were not the only beneficiaries of Charles’ generosity. Charles served on the Executive Committee and as director of the Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals for years and took an active part in the Massachusetts Total Abstinence Society from its beginning. He was involved in creating excursions for poor city children, including to Walden. In 1874, to kickstart a fundraising campaign for the debt-ridden Appleton Temporary Home for Inebriates, he offered to pay down one-tenth of its debt and to donate $10 yearly for the rest of his life. In 1875, he supplied every school district in his native town of Lunenburg with a cabinet organ and a full set of songbooks and donated money to the Lunenburg farmers’ club to encourage them to plant forest trees. Later, he donated globes and microscopes to the Lunenburg schools. Charles was also one of the founders of the Boston Union Industrial Association whose purpose was to find employment for and give assistance to the poor. [15] Ann (Tyler) Heywood showed up in newspapers in the 1870s, sometimes attending an event with her husband, but sometimes on her own. Ann was a donor to the North End Mission nursery. She served food (as did men) during at least one of the Poor Children’s Excursions to Walden, and in 1875 she and Charles were both appointed to the Committee in charge of Poor Children’s Excursions from the city. Ann served on the committee on her own for several years. In 1876, Mrs. & Mrs. C. L. Heywood were given a seven-piece silver tea service “as a token of appreciation of their generous gift of the reading room to the village of Waverley.” [16] Acton Connection In the 1870s, the Heywoods came to South Acton. As far as we can tell, their involvement started with a business opportunity. In 1869, William Schouler, owner of a South Acton mill, decided to sell out. An ad said “WATER POWER FOR SALE – Consisting of two privileges, within 30 rods of each other, one of 16 and the other of 9 feet tall, on an excellent stream, with a reserve of two ponds of 400 acres, altogether independent of the stream, with good factory buildings and dwelling houses, several acres of land with orchard and large grapery, situated on the Fitchburg Railroad, near the depot at South Acton, about 1 hour’s ride from Boston.” [17] Charles Heywood purchased the property on April 27, 1870 with a mortgage. In November, the old Schouler Mill burned, with damage estimated at $3,000. Fortunately, Charles had it insured. [18] Charles started a soapstone mill at the South Acton site. We were unable to find any details about the soapstone mill, unfortunately. There were soapstone quarries elsewhere in Massachusetts and in Vermont; Charles presumably was able to ship raw materials to Acton easily by rail. We were able to discover some details about Charles’ property from Acton’s 1872 tax valuation: Heywood, C. L., Belmont --

Charles owned water rights and the mill at approximately today’s 115-141 River Street and a house at approximately 140 River Street (no longer standing). The house, probably vacant for much of the year, received the wrong kind of attention in October 1875: “Some malicious person or persons have been throwing rocks through the windows of the house and barn near the soapstone mill, belonging to Supt. Heywood. A reward of $25 is offered for the arrest and conviction of the depredators.” [19] After Charles had paid off his mortgage, he started a new venture that was advertised in the Acton Patriot on September 26, 1878: [20] A NEW Grain & Grist Mill Has been fitted up with Corn Cracker and two sets of Stones at the Soap Stone Mill, on the Wm Schouler place about A half mile east of the South Acton Station, where Corn, Meal, Oats and Shorts will be offered at wholesale and retail at the lowest market price. Corn, Oats and Rye will be purchased in small lots of the farmer if offered. Mr. JOHN D. MOULTON, the well known miller of South Acton, has been employed to take charge. Orders left in order box at T. J. & W.’s Grocery Store will receive prompt attention. C. L. HEYWOOD. South Acton, Sept. 25, 1878 1878 seems to have been a time of change for the Heywoods, and it is likely not a coincidence that they started showing up more and more in Acton during that time. Charles “contributed liberally” to the building of the South Acton Universalist Church that was dedicated on Feb. 21, 1878, and he taught in its Sunday School. In June, he invited the children of the Sunday School there to make small floral bouquets with an accompanying letter that he would take to prisoners in Concord. [21] On August 27 of that year, there was a farewell celebration on the South Acton “grounds of Superintendent C. L. Heywood” for the fifty city children that he had hosted “at his summer home ever since July 1. The people of the vicinity turned out generally to the evening entertainment, which consisted of speaking, illuminations, bonfire, music by the Acton band, fireworks, and a general jollification.” [22] Ann’s role as hostess of fifty children was not mentioned. In 1878, Charles Heywood resigned from the Fitchburg Railroad after a career that lasted about 35 years, including fourteen as Superintendent. He acted in an advisory capacity for the railroad for three more months, but he had many things to do. He was working on new inventions. At the end of the year, he filed five more applications that were primarily aimed at making railroads safer for employees and passengers, including improvements in signal lights, steps for rail cars, and cabooses for brakemen. [23]  Track Clearing Car Track Clearing Car Charles’ gristmill continued. He added a horse shed at the grist mill for his customers’ convenience and ran ads in the Acton Patriot. [24] The Patriot reported on June 26, 1879 that: “Mr. C. L. Heywood and wife are to start Friday evening on an European journey, returning home in September.” [25] That fall, Ann F. Heywood was one of the first six women in Acton to register to vote in local school committee elections. That same fall, Charles was chosen by Acton as one of its delegates to the Republican Convention. During that period, the couple evidently considered South Acton “home”. [26] The 1880 Boston Directory, probably from information given in 1879, shows Charles L. Heywood as president of the Mercantile and Collection Agency of 8 Exchange Place, with a house at South Acton. [27] We have no other information about Charles’ involvement in what seems to have been a precursor to credit rating agencies. Because our collection of newspapers before 1888 is sporadic, we were not able to find any other mention of the Heywoods in Acton. However, the Heywoods showed up elsewhere. After Acton The 1880 census listed Charles and Ann living on Revere Street in Revere with Lincoln (age 11) and a few boarders. Ann continued to help with Poor Children’s Excursions and was elected to the executive committee in 1880. [28] Charles moved on to several new ventures that included contracting to fill what today we could call “wetlands,” but at the time were considered public health “nuisances.” Charles served as a director and then president of the Maverick Land Company that was filling the flats in East Boston that were expected in early 1881 to “be much required for railroad purposes during the coming year, and can be sold to advantage.” [29] Charles was involved with filling land at Fresh Pond in Cambridge and also apparently got involved in the project to fill Prison Point in Charlestown for the Eastern Railroad that seems to have been a quagmire for all parties. That scheme supposedly brought financial reverses to Charles, although we were not able to confirm that story. In addition to filling projects, he was involved with the Hoosac Tunnel Dock and Elevator Company and the Union Electric Signal Company. [30] Charles received a patent for an improved Track Clearing Car on April 11, 1882. Presumably, he continued to promote his inventions and in early 1883 took an extended trip to the West and Southwest and went to the National Exposition of Railway Appliances in Chicago where he was exhibiting his inventions. [31] Charles continued to support causes that he believed in. He served for eight years as treasurer of the Massachusetts Total Abstinence Society and lent his public support to the cause when needed. He continued working to help poor children and discharged convicts. Somehow, Charles found the time in November 1882 to present a travelogue to the Farmers’ Club in his native town. [32] In 1883, Charles went to work managing the construction of quarantine grounds in Waltham along the Fitchburg railroad. The quarantine grounds were to keep cattle, imported for breeding purposes, safely away from native stock. According to the Globe, the project was part of an effort by the federal government to systematically create an efficient quarantine system. [33] On June 23, 1883, Charles had been in Waltham, attending to his duties at the quarantine station. At about 4 o’clock in the afternoon, apparently trying to get to the station that would take him home to Waverly (Belmont), he was walking on one of the tracks. Reports vary; he may have been distracted by trying to warn another man that a passenger train was coming, or he may have been unaware that a freight train was running in a different direction from usual. Whatever the details, Charles, whose career and inventions had been aimed at improving railroad safety, was struck by a freight train. He was rushed to the main Waltham depot, attended by local doctors, and then taken by special train to Massachusetts General Hospital. Unfortunately, he died almost immediately after arriving at the hospital. [34] Charles’ death was a shock to many and was widely reported in the news. He was something of a celebrity and was widely admired for his success and generosity. Most reports, typically, either did not mention Ann at all or simply stated that he had left “a widow.” However, a couple of reports mentioned Ann as a person: “His wife was an estimable lady, and by her kindly encouragement has done much to make him what he was,” [35] and, probably from the same source, “Accompanying all the talk about the sad affair and the inquiries for particulars relating thereto were a general expression of regret and sympathy for his widow, who is a lady held in the highest estimation, and to whose efforts, it is said, has been due the greater part of her husband’s success.” [36] Ann Heywood’s life obviously would have been severely upended by her husband’s death. She had a teenaged son to care for and, most likely, a complicated set of financial entanglements left by her husband’s unexpected demise. Charles left an unusually long will dated June 20, 1878. In addition to providing for Ann, he created a trust for the benefit of his newly adopted son Lincoln and any wife, widow, or children Lincoln might have in the future. Given Charles’ ability to plan ahead, it is not surprising that there were many contingencies and potential recipients of money, including relatives and charities. Charles, who only had the benefit of education in the local schoolhouse, added, “I wish my said son to have the opportunity of obtaining, if he desires it, a liberal education, and, while I do not restrict his selection of a college or university, yet I would request that he should, before deciding, carefully consider the advantages afforded by the Massachusetts Agricultural College at Amherst.” He also left an additional special $2,000 trust, the income of which would be paid to Lincoln until the age of 25, at which time he would get the principal. The will directed that the income and the principal of that trust should be given by Lincoln “to Charitable objects, suggesting to him as worthy of special attention that class of the poor who bear in silence the burden of poverty, sometimes styled the silent poor.” Charles clearly hoped to train Lincoln in charitable giving. [37] In 1884, Ann and son Lincoln moved to Pawtucket, RI where Lincoln attended high school. Lincoln graduated with the class of 1886 and then attended Brown University for two years as a member of the class of 1890. In 1889, he entered the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and graduated in 1891 as a civil engineer. His senior thesis, completed with another student, was “A Plan for Widening a Stone Highway Bridge at Pawtucket, R. I.” After graduation, Lincoln again lived with his mother and worked for the Interstate Street Railway Company as an engineer. He married Edith Clapp on December 15, 1892. In July 1893, he became engineer of the town of Lincoln, RI and started working on designing and constructing a sewer system for part of the town and on creating a complete and coordinated system for the whole town. He and Edith had a baby daughter Hortense. Tragically, Lincoln died on Jan. 12, 1895. After what happened to his adoptive father, safety-minded railroad executive Charles, it was striking to read that Lincoln died of a disease that he was working to protect others from. “Mr. Heywood was taken ill the last of December with that dread disease, typhoid fever, which he, in common with many other engineers, through the agency of pure water supplies and proper sewerage systems, had been striving to render less dangerous to the community and less likely to become epidemic in thickly settled districts.” [38] He was 26 years old. One can only imagine the blow to his mother Ann, as well as to his wife. Joint owners of their home at Brook and Grove streets, Ann and Edith Heywood sold the property in early 1896. The 1896 Pawtucket Directory listed Mrs. Ann F. Heywood as having “removed to Providence.” [39] The 1900 census showed Ann F. Haywood (a widow born in Massachusetts in June 1825) as a boarder in the household of Anna Burrill in Concord, MA. She may have simply been staying for the summer, because the 1901 Providence, RI Directory shows Ann living at 733 Cranston Street. [40] We are not sure where she lived for the next few years, but Ann was in Pawtucket, RI when she died on November 14, 1904 of a cerebral hemorrhage. She was buried with Charles at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, MA. We found a death notice for Ann, but no full obituary. [41] On the other hand, we found that Charles was still notable enough in 1904 that a newspaper profile of a former Lunenburg teacher mentioned that he had taught “Charles L. Heywood, afterwards superintendent of the Fitchburg railroad.” [42] Sadly, that fame is long gone. In South Acton, though the railroad tracks remain and water still runs through the site, passersby would probably have no idea that mills were once there and that across the street, a generous couple once hosted dozens of city children in the summertime. References: [1] Boston Sunday Herald, June 24, 1883, p. 2; Fitchburg Railroad. Report of Committee of Investigation. Boston: Henry W. Dutton & Son, 1857, p. 6 [2] Brigham, Willard. The Tyler Genealogy; The Descendants of Job Tyler, of Andover, Massachusetts, 1619-1700. Privately published by Cornelius and Rollin Tyler, 1912, page 223 [3] Boston Evening Transcript, Sept. 17, 1864, p. 5 [4] For an overview of the Walden park, see Thorson, Robert M. The Guide to Walden Pond. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018, p. 167-168 and Springfield Republican, July 14, 1866, p. 1. For names, see among others: Boston Globe, July 3, 1874, p. 2; Lowell Daily Citizen & News, June 15, 1867, p. 2; Boston Journal, Aug. 24, 1866, p. 2. [5] Waltham Sentinel, Sept. 14, 1866, p. 2 [6] Waltham Sentinel, Nov. 30, 1866, p. 2 [7] Among many other reports of the park: Waltham Sentinel, June 4, 1869, p. 2; Boston Traveler, July 3, 1869, p. 2; Boston Journal, Sept. 1, 1870, p.4; Lowell Daily Citizen and News, July 14, 1870, p.1; Boston Daily Advertiser, Aug. 19, 1873, p. 1 [8] Boston Globe, May 8, 1875, p. 5; Boston Post, July 10, 1874, p. 4; National Aegis, Sept. 4, 1875, p. 3 [9] Patents #51,829 and 62,197; Railroad Gazette, Chicago, Vol. 2, No. 1, Oct. 1, 1870, p. 8 and Vol. 9, Jan. 26, 1877, p. xii; Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association. Exhibition Catalogue, September, 1865. Boston: Wright & Potter, 1865, p. 12 [10] Report of the Railroad Commissioners of the State of Maine, for the Year 1871. Augusta, Maine: Sprague, Owen & Nash, 1872, p. 46 [11] Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association. Exhibition Catalogue, September, 1865. Boston: Wright & Potter, 1865, p. 12; United States Centennial Commission. International Exhibition 1876 Official Catalogue. John R. Nagle and Company, 1876. In the Machinery Department, Charles’ Bridge Guard was #939c, but he seems to have had at least one other invention exhibited, #778c. [12] Boston Herald, June 25, 1883, p. 2 [13] Boston Traveler, May 11, 1869, p. 4 [14] Waltham Sentinel, Nov. 4, 1870, p.2; Boston Daily Advertiser, Jan. 7, 1870, p. 1; Boston Globe, May 25, 1875, p. 1; Boston Herald, May 30, 1883, p. 4; Cunningham, George A. History of the Town of Lunenburg. Vol. II, no publisher, p. 393; Waltham Sentinel, Dec. 22, 1865, p. 2 [15] Among others: Boston Journal, Nov. 14, 1871, p. 2; Boston Globe, March 26, 1873, p. 8, Boston Journal, March 25, 1879, p. 3; Boston Globe, Feb. 6, 1873, p. 8; Lowell Daily Citizen and News, Feb. 5, 1874, p. 2; Boston Journal, Sept. 12, 1883, p. 1; Boston Globe, July 3, 1874, p.5; Boston Daily Advertiser, Sept. 2, 1874, p. 4; Boston Globe, Feb. 10, 1875, p. 7; Boston Daily Advertiser, Sept. 14, 1875, p. 4; Fitchburg Sentinel, June 28, 1883, p.2; Boston Post, March 18, 1875, p.3; [16] Boston Traveler, Feb. 23, 1876, p. 4; Boston Journal, March 2, 1877, p. 2; Boston Daily Advertiser, Aug. 19, 1873, p. 1; Boston Globe, May 5, 1875, p. 4; Boston Daily Advertiser, March 15, 1878, p. 4 [17] Boston Journal, Dec. 17, 1869, p. 3 [18] Middlesex County Deeds, Vol. 1119, page 230-235 shows the purchase and the mortgage in April 1870. Vol. 1421, p. 280 records the discharge of the mortgage in January, 1877.; Lowell Daily Citizen and News, Nov. 19, 1870, p. 2 [19] Acton Patriot, Oct. 9, 1875, unpaginated [20] Acton Patriot, Sept. 26, 1878, unpaginated [21] Undated clipping in scrapbook at Jenks Library; Boston Sunday Herald, June 24, 1883, p. 2; Acton Patriot, June 13, 1878, p. 1 [22] Boston Daily Advertiser, August 28, 1878, p. 4 [23] Patents #216,403 - 216,307, all filed Dec. 24, 1878 [24] Acton Patriot, Dec. 5, 1878, p. 1; April 17, 1879, p.8; Feb. 19. 1880, unpaginated [25] Acton Patriot, June 26, 1879, p. 1 [26] Acton Patriot, October 2, 1879, p. 8; Boston Journal, Sept. 15, 1879, p.2 [27] The Boston Directory. No. LXXVI. Boston: Sampson, Davenport and Company, 1880, p. 471 [28] Boston Post, June 5, 1880, p. 3 [29] Boston Journal, Feb. 28, 1881, p. 1; The Boston Directory. No. LXXIX. Boston: Sampson, Davenport, and Company, 1883, p. 522 [30] Boston Sunday Herald, June 24, 1883, p. 2; Boston Sunday Herold, June 24, 1883, p. 2 [31] Patent #256,140; National exposition of railway appliances, Chicago, 1883. Guide to the National Exposition of Railway Appliances, Chicago (May 24-June 23, 1883). Chicago: Rand, McNally & Co., 1883, p. 93; Boston Sunday Herold, June 24, 1883, p. 2 [32] Boston Journal, Sept. 12, 1883, p. 1 and Dec. 12, 1881, p. 2; Boston Globe, Aug. 31, 1883, p. 2; Boston Herald, May 30, 1883, p. 4; Fitchburg Sentinel, Nov. 16, 1882, p. 2 [33] Boston Globe, April 18, 1883, p. 2 [34] Boston Globe, June 24, 1883, p. 1; Boston Sunday Herold, June 24, 1883, p. 2; Fitchburg Sentinel, June 26, 1883, p. 3 [35] Boston Globe, June 24, 1883, p. 1 [36] Boston Sunday Herold, June 24, 1883, p. 2 [37] Middlesex County Probate, #15,946 [38] George A. Carpenter and Morris Knowles. Lincoln C. Heywood A Memoir. Journal of the Association of Engineering Societies, Volume 14, p.56-57. Read to the Boston Society of Civil Engineers, March 20, 1895. See also The Tech, Vol. XIV, No. 17, Feb. 17, 1895, p. 170 and 172; Evening Times, (Pawtucket, RI), Jan. 12, 1895, p. 1 [39] Evening Times, (Pawtucket, RI), Jan. 25, 1896, p. 6; The Pawtucket City and Central Falls City Directory. No. XXVIII. Providence: Sampson, Murdock & Co, 1896, p. 236 [40] The Providence Directory. No. LXI. Providence, RI: Sampson, Murdock, & Co., p. 440. [41] Evening Times, (Pawtucket, RI), Nov. 15, 1904, p. 4 [42] Boston Sunday Post, Dec. 4, 1904, p. 6 [43] A correspondent granted us permission to use this photograph, which we gratefully acknowledge. Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

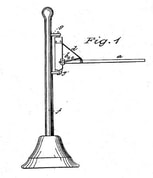

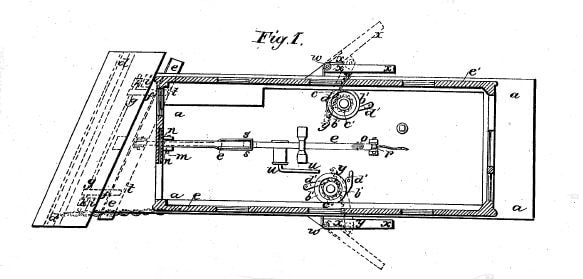

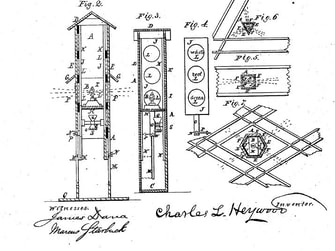

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

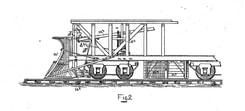

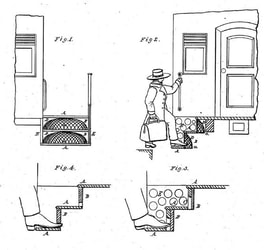

RSS Feed