|

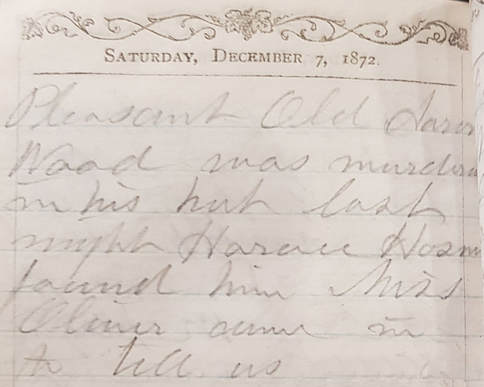

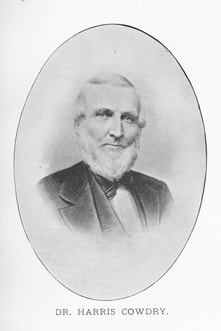

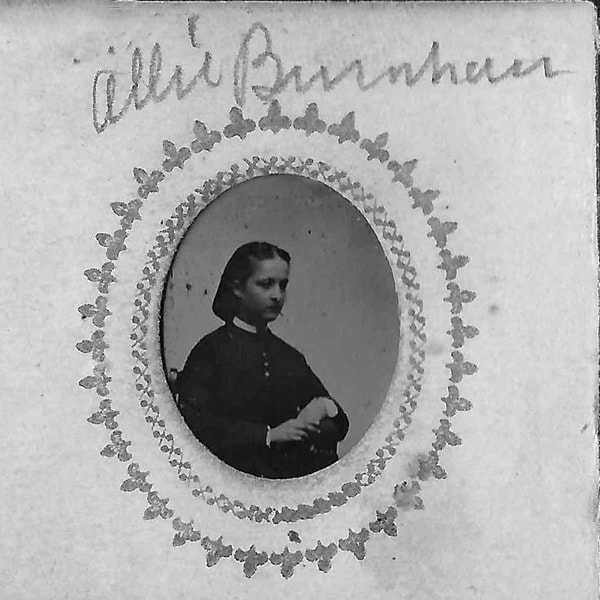

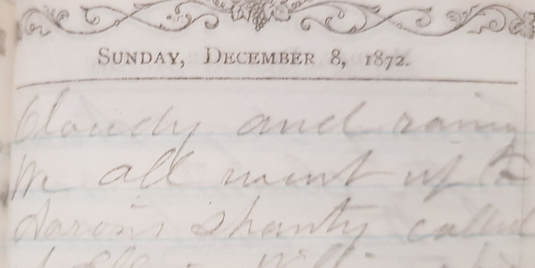

An unusual note appears in Acton’s 1872 death records, stating that on December 6 of that year, Aaron Wood (also known as Woods) was “murdered for his money.” We have not found any Acton newspapers from that period, but it was such a sensational event that we uncovered plenty of information about it and some misinformation as well. A recent donation of a box of old diaries showed us that the town’s news traveled fast even in those days. On December 7, Martha Ball of Acton wrote in her diary that “Old Aaron Wood was murdered in his hut last night Horace Hosmer found him Miss Oliver came in to tell us” The Boston Globe (Dec. 9, 1872, p. 6) reported that Aaron Wood had been killed the previous Friday evening. Tracks had been found leading south from the “house,” turning toward a pair of shanties in which railroad workers were living, then crossing the railroad, going through a field and some woods to the “highway” at Gallagher’s crossing, and then disappearing. The theory was that “some straggler who, being found by Mr. Wood searching for the money which the old man was popularly supposed to keep hidden in his house, knocked him down and stamped upon him.” The story was picked up by newspapers across the country, with different twists, (mis)interpretations, and some creative embellishments. Several papers reported that Aaron Wood was considered to be a wealthy old miser with money hidden in his home, while others reported that he was actually poor. Iowa’s Quad-City Times reported (incorrectly) that he had been shot by an unknown assassin. (Dec. 10, p. 3) Oregon’s State Rights Democrat placed the event in Acton, Pennsylvania, but mentioned that Aaron Woods was highly esteemed. (Dec. 27, p. 2). In Kansas, the Atchison Daily Patriot reported that he had lived for years in dirt and squalor. (Dec. 11, p1) The Springfield Republican (Dec. 9, p. 3 ) reported that Aaron Wood, a man of excellent qualities of heart, after having been “disappointed in a love affair, early in life” had lived in seclusion ever since, devoting himself to horticulture. A Memphis paper’s telegrapher or its reporter clearly missed some details; its Boston news section stated that “Aaron Wood, an actor, who, five years ago, lived alone in one part of the town, was found dead this morning in his dwelling. He probably had considerable money.” (Commercial Appeal, Dec. 8, p. 2) Researching the event nearly 150 years later, we were helped by finding so much written about an Acton story. However, we clearly have to be careful not to believe everything that we read. What Do We Know about Aaron Wood/Woods?Aaron Woods was born in Acton to Revolutionary War veteran Moses Woods and his second wife Hazadiah Spaulding. (His surname was spelled with an “s” in birth, baptism and some land records. It was often spelled without the “s” when townspeople were reporting on him, for example, in his death record, Martha Ball’s diary, and many newspaper reports. Both spellings could be considered correct.) Aaron grew up in his father’s house in what is now known as North Acton, on the west side of Main Street. His father Moses was a blacksmith and farmer who owned a fair amount of acreage in North Acton that included a shop and water rights on at least one brook. Though Aaron was living alone at the end of his life, he actually had fourteen siblings who were mentioned in town records. Aaron’s mother died in 1817. Aaron appears in Acton militia lists, serving under neighbor Uriah Foster during (at least) the 1817-1821 period. His brother Moses Jr. also served during part of that time. Moses Senior died in 1837. Late in his life, he had deeded his shop and water rights to Aaron. He willed his remaining real estate to two of his children, Aaron and Sally. Aaron never married, and almost all of Aaron’s siblings predeceased him. Presumably, he lived in his father Moses’ house with Sally until her death, but there is no record of Sally after her appearance in Moses’ probate record. At some point, Aaron allowed his shop to be used by Ebenezer Wood (no relation) who ran a “round saw” there as part of a pencil manufacturing business. In 1843, Aaron sold off Moses’ house, barn and 40 acres of land. It seems likely that Sally had died by that point; the deed does not mention her ownership rights. Aaron kept land on the east side of Main Street, including the shop. Aaron grew cash crops such as hay, apples, vegetables, and strawberries. He cut wood from his forested land, both for sale and for his own use. For many years, he lived in what had once been the shop, a structure without clapboards or plaster that must have been quite uncomfortable in the winter. To survive, he would have had his own farm products to eat and whatever animals and fish he hunted or caught on his land. Cold Spring Brook ran right by his abode. An 1873 Fitchburg Sentinel article mentioned that “its famous trout are known far and wide.” (July 14, p. 1) In later years, Aaron did not have a working stove and regularly bought bread and sometimes meat from a neighbor. It was a spartan, quiet existence until about 1870 when his life changed radically. The Framingham and Lowell Railroad was incorporated in 1870 to connect those two business centers via South Sudbury, Concord, Acton, Carlisle, Westford and Chelmsford. The railroad was built right through Aaron Woods’ land. He became “news” in the summer of 1871 when several papers reported variations of the story that “Aaron Woods who has lived a hermit life for seventy years in the eastern part of Acton, has never seen a train of cars. His cabin is on the line of the Lowell and Framingham Railroad, and he will soon see them if he don’t move.” (Boston Traveler, July 28, 1871, p. 2) The railroad began operation later that year. Aaron Woods’ compensation for the railroad’s “purchase” of a right of way was recorded on March 23, 1872. One has to wonder how Aaron felt about the “progress” in North Acton. The building of the railroad not only brought trains but also many workmen to the area in the early 1870s. Supposedly, Aaron Woods had issues with theft after they arrived. Theories about the murder quickly turned to these workers. The Inquest Immediately after the discovery of the crime, detectives from Boston were summoned to search for clues and interview witnesses. The selectmen of Acton offered a $500 reward for the arrest and conviction of the person(s) responsible for Aaron Woods’ murder. An inquest was held in the town hall. It was highly attended, because the citizens of Acton were “deeply interested in everything connected with this event, which to them is one of a lifetime.” (Boston Herald, Dec. 21, 1872, p. 1) Newspaper reports provided an amazing level of detail about the case. The jury of inquest included W.E. Faulkner (foreman), Henry M. Smith, Moses Taylor, James E. Billings, Charles Hanscom, T. G. F. Jones and E. G. Robbins. Witnesses were called. Dr. Harris Cowdrey presented his findings as the medical examiner, and Reverend Franklin P. Wood (no relation to Aaron) testified to having been at the shanty with the doctor while he did his work. Horace Hosmer, the neighbor who discovered the crime, testified that when Aaron had not shown up to pick up his bread as expected, Mr. Hosmer went to check on him and found the body. Former neighbor Hugh Cash mentioned that Aaron Woods had said many times that he expected to be murdered and that some years back “that scoundrel” had assaulted him. The “scoundrel” turned out to be a neighbor with whom Aaron had a land dispute. That neighbor was called to testify. He spoke about the land issue, but no one seems to have considered him a real suspect in the murder. According to news reports, the shanty was on a stretch of track without houses in sight, so there were no eyewitnesses of the crime. A couple of witnesses saw men in the vicinity around the supposed time of the murder. A man who was working on the railroad near sundown testified that he saw a young man, about 5’ 8” tall, coming from the direction of Aaron Woods’ shanty, looking backwards and acting suspiciously. Alice Burnham testified that she saw two men heading from a railroad crossing toward Mr. Woods’ place around 5:15 pm. The shanty had been ransacked, giving rise to the theory that the intention of the intruder had been robbery of Aaron Woods’ supposed wealth. The only real clue to the identity of the perpetrator was the trail of footprints. Luke Smith testified about finding tracks that had left blood on snow and on the sleepers (railroad ties). Apparently, the tracks had been made by size 8 boot that did not seem to have been worn much, as the prints were well-defined. Because railroad workers had been issued boots the previous week and the prints led past the railroad workers’ shanties, suspicion turned to them. There were 150 men working on the railroad at the time, and despite newspaper reports that two French Canadians were suspects, there was no direct evidence linking any particular worker to the crime. When reading newspaper reports of the inquest, we were quite surprised that investigators were able to find “bloody tracks for more than a mile.” (Boston Herald, Dec. 9, p. 1) Allowing for possible exaggeration, the story’s plausibility was bolstered by the diary of the weather-watching Mrs. Ball. Her decades of diary entries all start with a notation of the weather. Thanks to her, we know that Thursday, December 5, 1872 started out “pleasant,” but “a snow storm came on,” providing new snow on which tracks and blood evidence would have been obvious. The investigators had a day to measure and follow the footprints before they would have disappeared on Sunday, December 8, when Mrs. Ball tells us that rain arrived. Another complication for investigators was that the shanty immediately became a tourist attraction. On the 8th, Mrs. Ball mentioned that “We all went up to Aaron’s shanty,” presumably before the rain. Even without precipitation, it would have been impossible to preserve footprint evidence for long with the townspeople traipsing up to view the scene. Despite the intense interest in the case, the work of investigators, the witnesses, and the reward, at the end of the inquest, the jury’s verdict was that Aaron Wood died December 6, 1872, between four and seven o’clock in the evening from blows received from “some person or persons to the jury unknown.”

Two years later, a crime spree by a local man led townspeople to decide that he must have committed the murder as well. Acton made the newspapers again. The perpetrator went to jail for theft and breaking and entry. Apparently, there was no evidence to pin the murder on him, and he was never charged for it. The Aaron Woods case was never solved. Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed