|

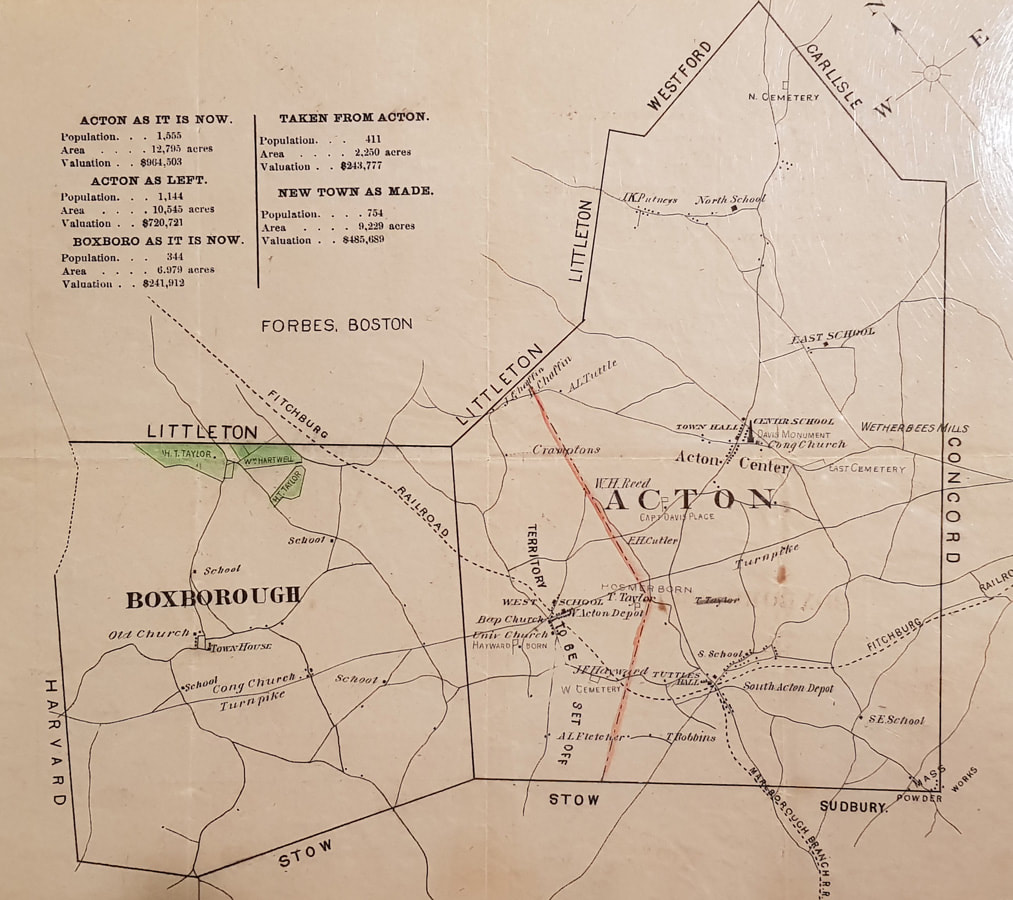

2/23/2021 West Acton Tried to SecedeIn our collection are two maps of Acton and Boxborough with a red outline around part of Acton, dating back to 1868-1869. At that time, residents of the western part of Acton were proposing to secede and join with Boxborough in creating a new town. Shown with the maps are the two towns’ relative populations, areas, and tax valuations, and how those would change if the proposal passed. The new town would take 26% of Acton’s population, 18% of its area, and 25% of its tax valuation. Previous local historians have puzzled over this village uprising (see references), but recently the Society was fortunate to be given access to a memoir from George C. Wright that discussed the West Acton secession proposal from the perspective of someone involved. Having access to digitized newspapers from the time added other details to the story. Decisions over the exact route of railroads and the location of depots led to changes in the relative fortunes of many towns and villages in the 1800s. Some boomed while others were passed by. To Boxborough residents in the 1860s, this was an issue of great importance. After failing to get a depot of their own, Boxborough residents generally went to West Acton to send their produce to market or to get to the city themselves. For most of Boxborough’s inhabitants, the nearest store was in West Acton. The central issue from Boxborough’s perspective was that the railroad had changed West Acton’s fortunes for the better. Boxborough residents were helping it to thrive, and they wanted some of the tax benefits. Underlying some of the agitation was probably the fact that businessmen with Boxborough roots had moved to West Acton, prospered, and contributed to the growth of their adopted village. George C. Wright wrote that about the time that the railroad came through in the 1840s, there was a small “boom” in West Acton, a place that had previously barely had enough economic activity to be called a village. (p.2) Though South Acton eclipsed it as a center of industry and mercantile activity, West Acton certainly grew as a result of the railroad. While presumably Boxborough’s farmers profited personally from having a railroad nearby to take their goods to wider markets, one can understand that they wanted the benefits for their town that they saw accruing to their neighbors each time they headed east on the turnpike. The actors in the secession drama seem to vary depending upon who was telling the story. The petition to the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives of Massachusetts, published by the town of Littleton, stated that the 57 signers were a mix of Boxborough and Acton citizens. However, after tracing each signer, we were able to find a Boxborough listing in the 1870 census or other evidence of Boxborough residence for 50 of them (plus another whose name was probably misspelled). Two signers had lived in both Boxborough and Acton, and four signers’ residence eluded us. Absent from the petition are the names of the quite well-known businessmen of West Acton with roots in Boxborough, among them West Acton Meads and Blanchards, and George C. Wright (who spent his teenage years in Boxborough). According to Phalen’s History of the Town of Acton, the petition’s supporters were the majority of the people of Boxborough and “the disgruntled minority” of Acton citizens who were trying to create a town “cut to their own pattern” that, by weight of numbers, they would be able to dominate. Phalen said, “The coterie in West Acton that started the scheme was motivated by no altruistic notions with respect to the established families of old Boxborough.... Very shortly the rural community would have found itself perpetually out-voted and more or less ignored except as an expansion area for its vigorous and ambitious new bedfellow.” (p. 203-204) Based on the published list of petitioners and Phalen’s history, we might have thought that the proposed new town was really a “Boxborough issue” with the support of a few West Acton outsiders. However, George C. Wright’s version of events contradicts that conclusion. George C. Wright and West Acton’s Boxborough natives were extremely generous to West Acton and did much for its development. (See our blog post on George C. Wright.) Over the long haul, they did not come across as the disgruntled “coterie” that Phalen described. Nonetheless, apparently George C. Wright not only approved, but was a leader of the secession effort. He wrote that the proposal was backed by “a large majority of the citizens of West Acton,” including native Boxborough businessmen, and that “I was heartily in favor of the project and was chairman of the committee to secure the necessary action by the legislature. I did everything I could to carry the measure through, sparing neither time or money...” (p. 6) Town meeting records from Acton show that the proposed secession of West Acton had been discussed at the November 3, 1868 town meeting. The citizens of Acton as a whole disapproved. The vote was 204 to 45 in favor of a resolution that included the following statements:

The town then chose a Committee of seven “to save the town from prospective trouble and ruin.” They were authorized to hire counsel at the expense of the town of Acton. The chosen committee members were Luther Conant, William W. Davis, John Fletcher Jr., George Gardner, Aaron C. Handley, William D. Tuttle, and Daniel Wetherbee. Apparently undeterred by opposition from the rest of the town of Acton, the proponents of the proposal moved forward. Both sides hired lawyers. On January 18, 1869, the petition to create a new town (officially known as the petition from “H. E. Felch and others” ) was referred from the Massachusetts House of Representatives and Senate to the (joint) Committee on Towns. (The Committee was surprisingly busy with other proposals as well; disagreements over territory were not unique to Boxborough and Acton. In fact, Boxborough and Littleton had their own disagreement before the Committee in 1868 and 1869, illustrated by the green-shaded properties on our maps.) The Acton committee against the proposal apparently got busy gathering signatures. Between January 27 and Feb. 2, “remonstrances” were presented by lawyers and referred to the Committee on Towns. The remonstrances were labelled with the name of the first signer “and others”, so we know that five anti-secession remonstrances were filed from Acton with the first signers being W. E. Faulkner, Daniel Wetherbee, Luther Conant, Lewis F. Ball, and George Gardner. (The latter was ”George Gardner and 18 others of West Acton” according to the Boston Herald, Feb. 3, p. 1.) On Feb. 2, there was also a remonstrance from Simeon Wetherbee and 22 others of Boxborough. According to the final report of the Committee on Towns (in our archives), the total number of remonstrants was 313. Those in favor of the petition also obtained more signatures. On Feb. 8, the Journal of the House shows that “Mr. Fay of Concord presented the petition of Wm. Reed and others of Acton and Boxborough, in aid of the petition of H. E. Felch and others.” (p. 103) Non-resident owners of real estate in Boxborough signed a petition in favor of the new town that was presented on Feb. 10 (“Henry Fowler and Others”). The total number in favor mentioned in the final report of the Committee on Towns was “about one hundred and forty or fifty petitioners.” (p. 2) The number is surprisingly vague, given the fact that the opposition signatures were counted exactly. Signing was obviously not considered enough; many supporters and opponents attended the hearings. The Springfield Republican reported that at some point during the proceedings, the Blue Room “was crowded almost to suffocation by Acton and Boxboro people.” (Feb.20, 1869, p. 2) In this midst of the petitioning and remonstrating, a call apparently went out for funding and naming the new town. A correspondent signing as “Maxwell” wrote to the Lowell Courier (Jan. 13, 1869, p. 2): When the petition is granted and the new town is born, it is reported, should some gentleman wish to have the town named for him, his wish can and will be granted should his name be acceptable to the people and his bequest or donation, to the town, be a million or some considerably less. We learn that a gentleman residing not far from Shirley and Groton Junction stands ready to give his hundreds, if not thousands, to have the town take his name. Clearly there were rumors about the possible naming of the new town. Local historians have tried to determine what the name might have been. Phalen stated that no records mentioned a new name, although he had heard a “legend” the name would have been Bromfield. (p. 203-4) Local historians in the 1990s-2010 era accessed the memory of a couple of descendants of long-time local families who thought that the name was to have been Blanchardville. Given later Blanchards’ generosity to both towns, this was a plausible name. However, with the advantage of access to digitized newspapers of the 1860s, we investigated what was said in the 1868-69 period. We did not find contemporary mentions of Blanchardville (except for a village of that name in Hampden County, MA), but we did find in the Boston Traveler of Feb. 13, 1869 (p. 4) a report on the Boxboro’ and West Acton case that mentioned “the proposed new town of Bromfield.” The Springfield Republican (Feb. 20, p. 2) confirmed that the name was “Bromfield.” The Lowell Courier of Feb. 26 (p. 3) reported on the “very lively and interesting” set of hearings held on the new town of “Bramfield.” It also stated that the petitioners from Boxborough suggested that “such annexation would increase the value of their real estate by giving them a local habitation and a name, particularly the latter.” The implication seems to be that there was money to be gained from the new name, but whether there was actually a Mr. Bromfield (or Bramfield) “ready to give his hundreds, if not thousands,” we have not discovered. Newspapers were also helpful in describing the progress of the proposal. The Boston Journal reported that the Committee on Towns took up the petition on Monday Feb. 1, 1869 and planned to visit the towns in question the following Friday. Boxborough was nearly unanimously in support of the proposal while 4/5 of West Acton supported it. (Feb. 2, p. 2) The Lowell Courier, seemingly with an opinion on the matter, reported that “Nearly all the people of both places are in favor of the union. Some opposition will be made by the town of Acton, which, however, will have left in case of division a territory larger than that of the new town, and nearly double the number of inhabitants.” (Feb. 3, 1869, p. 2) On Tuesday Feb. 9, the Committee on Towns held an early hearing on the matter. “Nearly all the legal voters of Boxboro were present, quite depopulating the town.” (Boston Herald, Feb. 9, p. 4) The arguments centered on the growth of West Acton since the building of the Fitchburg railroad and that “many of the people of Boxboro had removed thence to get the advantages of the railroad, and all of their business and other interests centered about that locality. The opposition to the project comes from the town of Acton, the people of West Acton and of Boxboro being united in favor of it.” (Boston Herald, Feb. 9, p. 4) On Feb. 10, the Boston Post (p. 3) reported that the hearing continued, but the Post’s only other comment was that “Several witnesses were called. Their testimony is not of general interest.” Fortunately, The Lowell Courier (Feb. 26, p. 3) filled in more of the arguments. In addition to Boxborough’s assertions, West Acton petitioners claimed that the new town would benefit them economically. (Their plan seems to have been that the town hall and business of the new town would be located in West Acton.) Notably, there was no claim that the town of Acton had treated them badly in the past. On the other side, the anti-petitioners from Boxborough wanted to leave their town as it was, quiet and peaceable. They feared that any benefits of the arrangement would go to West Acton, which would dominate them numerically. Acton’s opposition included “all but three of the legal voters outside of the territory proposed to be set off, with nineteen living on the territory”. Among their objections, the Courier noted that the section to be taken from Acton included some of the town’s best farming land. The result would be an awkwardly-shaped, narrow town with, they feared, decreased property values, increased taxes, and impairment to their schools. “Why, they ask, should they be impoverished that others may be enriched?” Other arguments listed in the final report of the Committee on Towns were the fact that Acton had just recently built “a large and commodious town hall,” that they had paid to build and repair roads that would now be part of another town, that having a smaller population would defer for even longer the hope of a high school in the town, and that this could set a precedent for South Acton that might seek its own alliance with the thriving village of Assabet. (p. 3) George C. Wright’s memoir added: [A] strong opposer was the late Dea. Silas Hosmer, one of our own citizens. Dea. Hosmer went before the Committee on towns with a carefully prepared paper opposing the proposed dismemberment of the town of Acton, and the point which seemed to carry the most weight with the committee was his statement that every patriot, whose bones are in the Davis monument, was born in the part of Acton which it was proposed to set off for a new town, and two of the three men went from homes in West Acton to die for their country on April 19, 1775, so that, if the proposed measure should be carried through, there would appear an anomalous state of things, namely, the situation of an imposing monument in one town in honor of men belonging to another town. (p.6) The legislators no doubt would have been reminded that much of the monument’s cost had been funded by the Commonwealth. George C. Wright also mentioned that “Among the influences which worked against us, one was found in George Parker, Esq., a member of the legislature, who was a native of Acton and a son-in-law of Rev. J. T. Woodbury. Mr. Parker’s opposition was very earnest and effective.” (p. 6) Rev. Woodbury had been the driving force behind getting the grant for the monument. (Research indicates that George Gedney Parker, born in Acton to Asa and Ann M. Parker, married Augusta Woodbury. In 1869, he was a lawyer in Milford, MA. He had not yet been elected to the legislature, but another of Rev. Woodbury’s Milford lawyer sons-in-law, Thomas G. Kent, was actually part of the Committee on Towns.) The closing arguments to the petition debate were made to the Committee on Towns on the morning of February 13. Lawyers for the opposition, Hon. David H. Mason of Newton and Samuel W. Butler, Esq. made the arguments, including an apparently eloquent recap of Silas Hosmer’s objections. Also mentioned was the “fact that the village of West Acton, by its numerical superiority, would control the proposed new town of Bromfield, and that not the slightest necessity was shown for the change, or for breaking across old town lines.” (Boston Traveler, Feb. 13, p. 4) Lawyers for the petitioners, George M. Brooks and George Heywood of Concord, spent 1-2 hours making their case that Boxborough needed help to stop its decline, that Boxborough and West Acton would benefit from the plan, and that the evidence for making a change “came from the best men in West Acton and in Boxboro’.” (Boston Traveler, Feb. 13, p. 4) The next week, the Committee on Towns held a private meeting. The result was its report of February 18, 1869 in which “with all but entire unanimity” the Committee found that though the town of Boxborough was indeed too small, if the petition were granted, both the new town and Acton would be too small. The committee was unconvinced that the new town would grow, having “no water power and no manufacturing interest well established.” (p. 4) They foresaw future political problems with a town “center” situated so far from the western boundary of the new town. Overall, the petitioners had not proved that the formation of a new town was best for the “public good.” In fact, they added: ...rather than cripple Acton in her enterprise or encroach upon her historic limits for the benefit of [Boxborough], as her inhabitants have no desire to retain their name and distinct organization, it will be an easy task to so apportion her territory to other towns as to benefit all and injure none; but with this matter the Committee are not asked and do not desire to interfere. (p. 4-5) Boxborough’s willingness to give up its identity ended up working against the proposal. It is very likely that many residents of Boxborough over the years have looked back on the decision as a fortuitous one for their town in the long run. Boxborough has maintained its identity and grown its own way. Proponent George C. Wright, looking back in his later years, had this to say from the perspective of his decades in West Acton: The result was we were defeated, and as time has passed, I have come to feel that it is just as well our measure failed to be a success. In these last years, the town of Acton has done everything for us as a village that we could reasonably ask to have done. References (in addition to newspaper articles cited in the text):

Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed