|

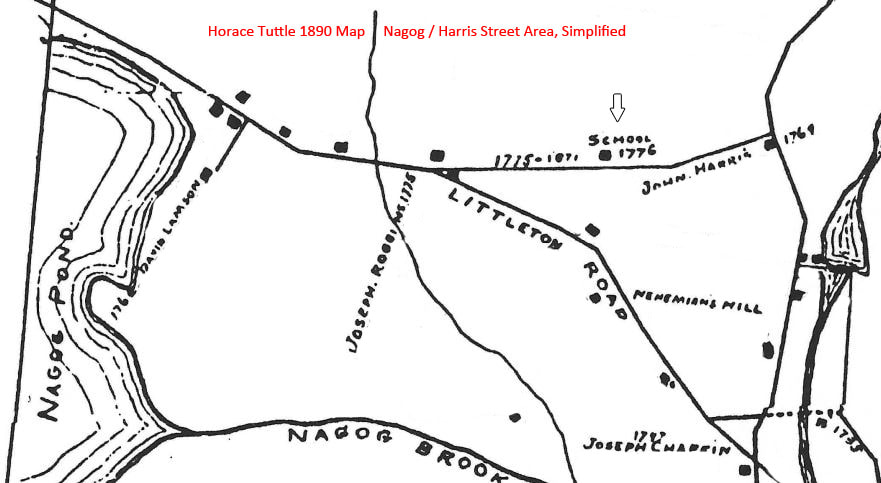

5/16/2018 Acton's Disappearing Schoolhouses Acton has utilized many school buildings throughout its history, most of which are long-gone or unrecognizable. The most recent to disappear was the red brick schoolhouse on Harris Street that was torn down earlier this spring. We thought it an appropriate time to review the history of Acton’s school buildings. The Society has documents and maps that have tried to pinpoint the location of Acton’s early schools, the result of much work by local historians including James Fletcher, Horace Tuttle, Ida Hapgood Harris, Harold Phalen, Florence Merriam, Elizabeth Conant and others. In addition, Acton Memorial Library has made early town meeting records easily accessible online. But even with those resources, it is still a very confusing subject. Early schools were temporary and seasonal. Historical documents refer to people, structures, and areas that are unfamiliar today. (Where were “Deacon Brookses Squadron” and “Capt Haywards Corner”?) Seemingly logical labels (“north”, “southwest, “east”) referred to various divisions of town at different times. We have some payment records from early years, but it is not clear whether the payments to individuals “for schools” were for their own teaching and whether a school was actually kept on their own property. As time went on, schoolhouses were built, used for a time and then abandoned, moved or creatively reused. Town meeting records give us clues, but one has to be careful about making assumptions based on a favorable vote at a town meeting. Acton had a habit of voting on an issue and later voting to reconsider the same issue, sometimes multiple times. On school matters, there was a high probability that a vote would be overturned within the next few months or years. Stepping bravely (or foolishly) into the quagmire, we begin our survey of Acton’s schools. After a vote on March 3, 1739/40 not to “erect” schools, apparently the town voted to have a “reading, riteing and moveing Scool” in March 1740/41 (its funding was not clear). Acton’s public education was more definitely organized by a vote in December 1743 to divide the town into three parts, holding a school in each section. In the earliest years of Acton’s history, classes were held on private property by individuals who were willing to teach. Exactly how the students were accommodated was not specified in town reports. The individuals who kept the schools generally farmed, so presumably classes were held at times of the year when teachers and students were not needed for agricultural labor. As time went on, expenditures for a “schoolmaster” began to appear in town reports. Very early, the issue of equity arose; there had to be enough schools in town that all families had access to education for their children within a reasonable distance. The number of school districts, (sometimes known as societies or squadrons), was a recurring issue at town meetings. After the initial three districts in 1743, the number of divisions varied from four to seven. The first mention of town-owned school buildings appeared in town meeting records in 1771. On May 27, the town voted that Acton should have seven school houses in the center of each division of the town. Four had already been built privately and were to be purchased and repaired by the town. Three new Schoolhouses were to be built, “Eighteen feet in Length and Sixteen feet wide” but the districts could, at their own expense, upgrade them to twenty by eighteen feet. They apparently were to have four windows, plaster ceilings and at least partial plaster walls. Locating North Acton's Schools Starting our survey of Acton’s schools with the schoolhouse(s) in the vicinity of Harris street, we find that the 1771 list of proposed school locations did not include that area. There was already a schoolhouse near the Healds’ residence on present-day Carlisle Road and apparently another near Josiah Piper's on “Procter’s” Road (now Nagog Hill Road) that could have served families in the northern part of Acton. After some deliberation, on March 2, 1772, it was decided to leave the schoolhouse where it stood near Josiah Piper's. After the schoolhouse vote, complaints started and a series of re-votes followed. In particular, “Samuel Fitch and a Number of His Neighbours” thought themselves injured by being "to[o] Remote from Any School.” (March 1774). The town's response was that Mr. Fitch and his neighbors could have their school tax money to be used for alternative schooling. Existing town maps do not show the location of Samuel Fitch’s house in Acton, but we know from the Tuttle/Scarlett maps that at least some of the neighbors mentioned, (David Lamson and the widow Temple), lived in the Nagog Pond/North Acton area. (It was the same area that included John Oliver’s farm, the subject of another blog post.) On January 4, 1775, the town voted to build a schoolhouse “to accomidate Samuel Fitch and others.” One might think that was the end of the story, but on May 14, 1776, the town again voted that the Selectmen should build a School House in “Samuel Fitchs Society.” Probably based on that vote, Horace Tuttle’s 1890 map dated the first Harris Street North Acton schoolhouse at 1776. That may have been optimistic. On January 31, 1780, the town was again asked to vote on building the same schoolhouse and postponed the vote. In May, 1780, the town “voted that the Committe that was Imployed to Build a School House in mr Samuel Fitchs Society Do hire money in Behalf of the Town to Pay Said mr Samuel Fitch for what he has Don.” Clearly, Mr. Fitch had taken matters into his own hands. Unfortunately, the exact location and whether a schoolhouse was fully built at that point is not clear from the town meeting records. Around that time, the redistricting of families that were set off to the District of Carlisle necessitated another vote on the location of a schoolhouse, combining the families in the Fitch area with those who had been in Lieut. John Heald’s district (the “northest part of this town”, November 20, 1780). Money was voted toward building the schoolhouse at that time. The next period in which school buildings were discussed was the 1790s. On November 2, 1792, the town voted to reduce its school districts from seven to four. That was a short-lived plan. After proposals and counterproposals, on May 6, 1795, the town settled on five school districts and decided that “every Person Shall have the Liberty to Join the District to which he Chuses to belong and his Scholl [school] Rate Shall be expended in the School”. (Acton’s policy of school choice started early. It was also subject to many later votes.) Five schoolhouses were to be built including one “where the School House Stands near John Harris’.” This is the first direct mention that there had been a school near the location of the (later) brick school house. That was a welcome moment of clarity for us. It was temporary. In the 1796-1797 period, there were numerous town meetings in which the town was asked to reconsider, repeatedly, previous votes on school districts and schoolhouses. The warrant for the May 1796 meeting asked the town to “Reconsider all the votes that have been passed in the town meetings Respecting the Districting the town for Schools and building School houses for Seven years past” and in January 1797, the town was asked to reconsider all of their former votes on the issue. On May 1, 1797, the town voted not to fund the building of the five schools. Clearly, the decision-making process was not going well. In October 1797, a committee was formed to “fix a place for a School house north District”. Based on the voting chaos, it seems unlikely that a new school was actually built before the town’s school districts were consolidated around 1800. Town records discussed selling old school house(s) in the “east” part of town, and the Schoolhouse “near John Harris” was sold to David Barnard for $31.25 (Dec. 3, 1800). The neighboring residents were clearly not happy, because the town was asked to vote on building a schoolhouse in the Northwest part of town in December 1801. The town voted it down. According to town histories, for a period of about thirty years, the north and east districts were combined. There is no mention of a “North” school district in the records of those years and the sale of the schoolhouse indicates that the Harris Street site was not in use at the time. Instead, a schoolhouse was built approximately at the current intersection of Davis and Great Road. An 1830-1831 survey map shows a school at that location (and not at Harris Street). According to Ida Hapgood Harris’s 1937 school history, “Old residents relate that 80 pupils were there at one time. This was probably built around 1796.” (The document is at Jenks Library.) Leaving out occasional indecision during the early decades of the nineteenth century, on May 13, 1839, the town voted to split the “east” district again and build a brick schoolhouse in its "northern part" by November 1, 1840. Given the uncertainty of any vote being realized, we were dubious about claiming that the schoolhouse actually was built at that time. However, it must have been built then or soon thereafter, because in April 1844, the town voted that the North Acton district could put seats into their schoolhouse, as long as the town did not incur the expense. The residents must have refused to pay for the seating, because in April, 1845, the town provided $12 to “put seats into the North School house in the place of stools which are now broken”. (The students must have had an uncomfortable year.) By 1847, the town started printing the school committee’s annual reports, so we have a much more complete (and colorful) picture of what was going on with the schools after that time. From the 1849 report, we find that by then, the whole town had new schoolhouses. The school committee took a look back at the schoolhouses they replaced: “...now entirely vanished from our view – the old, square, four-roofed, one-storied, red school-houses.... with their little porticoes made to store wood and to trample clothes in... the strange and uncouth carvings, etchings and engravings which enriched them within and without. We remember too, the broken floors, the rickety and disfigured seats and benches, the blackened and dilapidated walls, and above all the ventilating apparatus, called windows. Yet they were cheerful places... But they have passed away, and other houses of a very different model stand in their stead.” Confirming that the brick school house had indeed been built, the committee wrote: “In the place of the old house on the great road are built two substantial and convenient brick houses, capable of accommodating fifty scholars each. They have good woodrooms and clothes rooms, and are furnished with black boards and Mitchell’s large map of the world; these last were purchased by subscriptions of the friends of progress in the district. These houses were built at a cost of $525 each, exclusive of the land and its preparation.” Despite the optimistic tone of the 1849 school committee, reading later town reports, one has to think that upkeep of the schoolhouses was a constant struggle. By 1851, the school committee was admonishing all of the school districts to attend to repairs so that “there is nothing to excite the evil propensities of the young destructives.” Vandalism seems to have been a perpetual problem. The 1858-1859 School Committee reported about the winter term: “Of this term for obvious reasons we shall say but little. (Sadly, that story is lost to history.) If the advancement in this, and preceding winter terms has fallen below the expectations of the parents, they should remember that such a miserable, dilapidated, cold, cheerless, uncomfortable and lonely old school house is not the place to look for anything remarkable. The pupils one day the past winter, found a large supply of shavings, in consequence of one of their number falling through a defective part of the floor. Occasionally the boys, out of school hours, amuse themselves by jumping from the floor and touching the ceiling, a feat that most of them can easily accomplish.... The location of the stove is such that [heat] is very unequally distributed.... Indeed the house may be comprehensively described as almost a perfect model of what a school house ought not to be." By the 1863-1864 report, we read: ”...we wish to speak of our school-houses; and in no very flattering term either. We know there are a plenty ready to say, they are good enough; what would be the use to build better ones, for the scholars to tear in pieces.... Why, they exclaim, “some of our school-houses have not been built comparatively but a short time, and just look at them.” That is what we say, LOOK at them, and carefully too; and we think you will come to the sage conclusion, that they are ill planned, poorly built, shammy things.... We do not believe the children and youth in this town are so much worse than they are in others; and we know they have large, convenient, and even ornamental school-houses in other towns, and they are kept well too. We believe if this town would build some good school-houses, convenient and well finished, that our scholars would take pride in keeping them so. We do not think it a good way to cultivate feelings of respect for public property, by having constantly before the eyes of our children defaced benches, dingy walls, and plastering hanging from the ceiling here and there, in a manner to tempt even those not inclined to mischief, to hit it a poke and tumble it down.... We think all should be as willing to be taxed to raise money to build good school-houses for their children to attend school in, as they would be to raise money to build a good town house to attend town meeting in, and we think if the town is able to have a town house worth some eight thousand dollars, it is able to have school-houses worth as much.” Ten years later, the town agreed that the brick building on Harris Street had reached the end of its useful life as a school. Charles I. Miller’s reminiscences of North Acton (at Jenks Library) stated that a wooden replacement was built during the fall and winter of 1873 while school was still being held in the old brick schoolhouse nearby. It was a time of change; the North Acton railroad depot had just been built at the end of Harris Street. At that time, only one house and barn were visible from the station, but the area soon grew. After the brick schoolhouse was taken out of service, it became a private dwelling. The wooden schoolhouse served for 26 years. The conflict between those who wanted schoolhouses close to home and those who wanted to achieve the efficiency of having larger, “graded” schools went on for decades. By the 1890s, small, ungraded schoolhouses were falling out of favor. It had become inefficient for one teacher to try to teach a broad range of subjects in one classroom that held up to seven grades’ students. The East district was merged into the Center school, but the North Acton district held out longer. Clearly frustrated, the Superintendent wrote in his 1897-1898 report that students in “out-lying districts” had:

a tendency to insubordination, which seemed to have its foundation in the idea that parental influence was paramount in all school matters pertaining to their district.... it prevails in out-lying districts generally, and is quite well developed at North Acton.” [page 59-60] Eventually, even the North Acton school was closed. In September 1899, its former students were transported to the Center school which then was divided into primary, intermediate and grammar “schools,” each with three grades apiece. The former North Acton teacher, the long-serving Ella Miller, came with them. The wooden school house at 52 Harris Street was sold off and became a dwelling. That piece of Acton school history still stands. Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed