|

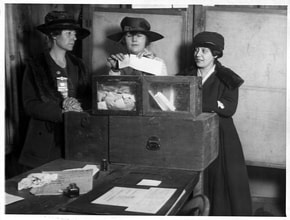

8/26/2020 Finally, Acton Women Could VoteIn August 1920, the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote in the United States. Looking back from today’s perspective, one would expect the event to have been celebrated in the local paper, the Concord Enterprise, with a front page announcement and large headlines.* In fact, the reporting was subtle enough that it was not clear from the paper when the key event actually took place. The September 1 Enterprise did present a table on page six that broke down the states’ votes, classifying them by political party. Among the twenty-eight “Republican” states that had ratified the amendment were Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. The “Democratic” ratifying states were Arkansas, Arizona, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah, and finally Tennessee. Connecticut, Vermont, Florida and North Carolina had not yet made a decision, and seven states had rejected the amendment. (The Enterprise missed Oregon in its listing, so the totals did not actually add up to the necessary 36 states for ratification.)  Courtesy Library of Congress Courtesy Library of Congress It had been a long, difficult slog to get the vote. Women had to overcome a widespread belief that they were incapable of understanding important issues and of thinking for themselves. They also had to deal with opposition to the idea of women venturing out of their allotted “sphere.” Two examples from previous years’ Enterprise columns illustrate what women were up against. During the 1895 Massachusetts campaign to allow women to vote in local elections, a letter appeared in opposition that stated that “... women, by the very nature of their being, their social and domestic duties, do not and cannot have a practical knowledge of the wants or needs of a large town or city. ... their political action will be governed by their prejudices...” (Oct. 24, 1895, p. 4) This opinion elicited a rebuttal that said in part “It is surprising that in this age of advancement and higher education of women, a man of average intelligence can be found bold enough to affix his signature to an article so foreign to reason and justice.” (Oct. 31, 1895, p. 4) The South Acton writer of the rebuttal clearly overestimated the open-mindedness of the time. Twenty years later, the Enterprise said in a supposedly fair-minded editorial: “There are a great many deep thinking, intelligent men who honestly oppose suffrage for they believe the success of the movement in this state would project women into a sphere for the activities of which they are totally unfitted. They believe that the ideal balance maintained in the home would be destroyed and that no great good could be obtained through doubling the voting strength of the state.” (Oct. 27, 1915, p. 2) World War 1 changed some attitudes. Among the many ways in which women contributed during the war, women (including Acton’s Lillian Frost) went overseas to work as nurses, ambulance drivers, telephone operators, and in other support roles. The June 18, 1919 Enterprise mentioned that at least 184 nurses had died as a result. (p. 6) One week later, Massachusetts became the eighth state to ratify the nineteenth amendment. No large headlines celebrated that event. However, on July 2, 1919, the Enterprise editorialized that “with the advent of equal suffrage there will be a betterment of living conditions, greater equality, and protection of the rising generations. There will be a cleaning-up of many filthy places, and a wiping out of the sore-spots that have disgraced the nation.” (p. 2) Clearly, when the women were finally able to vote in 1920, they had many expectations to deal with, some negative and others dauntingly optimistic. Once women’s suffrage looked poised to win, the Enterprise reported on efforts to ensure the success of women’s voting. A critical piece was getting women to register to vote. Because women could already vote for their school committee in Massachusetts, they could be enrolled as voters in advance of ratification. (For more information about female school committee voting, see our blog post.) When aspiring voters met with the board of registrars in their voting district, they had to show that they were citizens, at least 21, and able to read and write English and that they had lived at least one year in Massachusetts and six months in their voting district. They were also expected to answer questions about parentage and nationality and to prove naturalization if necessary. (Aug. 18, p. 4) The first election in which they could fully participate was a primary in September 1920. As pointed out in the Maynard column of the August 11 Enterprise, “With no district contests among the Democrats there is very little interest shown.” The Maynard Republican Women’s committee, on the other hand, announced a number of reasons for registering, including participating in a great historical event, honoring the 70 years in which “some of the ablest women of America gave their lives to the winning of this right for women”, and helping to “elect men who will look out for the children’s welfare” and “secure good working conditions for you.” (Electing women was obviously an issue for another day.) If those weren’t good enough reasons, women should register because they didn’t “want it said that the women of Massachusetts were behind the women of other States in meeting the responsibilities of citizenship.” (Aug. 11, p. 1) In Acton, registration was a success. On Sept. 8, the Enterprise reported that in South Acton, forty-nine women (and nine men) registered (p. 1), while in West Acton, “At the meeting of the board of registrars Thursday night, the number broke all records, when 80 women were recorded and 14 men were added to the list.” (p. 5) Acton Centre reported “quite a number” had registered for the primary and more were expected for the November election. (Sept. 22, p. 5) Though fanfare about the first election was fairly minimal in the paper, the West Acton reporter noted on September 15, “The women of Precinct 3 are to be congratulated on their good work at the primaries last week, when they cast their first votes. Mrs. Albert R. Beach cast the first ladies’ vote here.” (p. 6) Getting women onto the voter rolls was not enough. Women had to overcome people’s lack of faith in their abilities, judgment, and knowledge. One way to combat low expectations was through education. In Maynard, the Women’s Club sponsored a series of ten classes on government and the duties of citizenship. (Sept.8, p. 4) In Acton, there was so much concern about women’s ability to handle the physical act of voting that lectures were held to help: “A citizens’ meeting will be held in the vestry of the Universalist church on Thursday evening, Oct. 21, at 7:30 o’clock under the auspices of the Republican town committee. Miss Grace Carruth of Boston has been engaged speaker and will address the meeting upon the subject ‘How to Mark the Ballot’ and will be prepared to answer any other questions of present political interest. Similar meetings will be held during the afternoon of the same day at Acton and West Acton. All persons interested are invited to attend.” (Oct. 20, 1920, p. 1) The Acton Woman’s Club, a little behind, scheduled a speaker on Nov. 22 to help its members “in the study of simple non-partisan citizenship.” (Nov. 10, p. 8) Election day came on November 2. The first women voters in South Acton that day were Grace and Lyde Fletcher who had come back from Watertown the previous evening to be able to cast their ballots. (Nov. 11, p. 8) Another female voter in South Acton was Mary H. Lothrop who, with her husband Frank on the way to Florida, “took advantage of the privilege of absent voters and sent their depositions by mail.” (Nov. 10, p. 1) The vote was especially memorable for South Acton’s Carrie Franklin. Of obvious importance, she was able to participate in a historic moment, voting with her husband William in a national election. The surprise was that during the 45 minutes it took to cast their ballots and return, their home was burgled. Money and Mrs. Franklin’s jewelry were stolen. The perpetrators had apparently watched them leave the house. It turned out to be three boys from Maynard, later found by the railroad tracks with Mrs. Franklin’s watch. Overall, when the Enterprise reported on the election of 1920, it had to note that the women of Acton had managed to vote without disaster. In South Acton, “Out of a total of 313 registered votes, 278 votes were cast, or about 89 per cent, which is probably the largest proportionate votes ever cast here. The counting was completed and returns complete at 6:30 p. m. The women manifested great interest and marked their ballots with ease and rapidity.” (Nov. 3, p. 4) In West Acton, the report was, “No Ballots Thrown Out – With 347 voters in Precinct 3 there were 322 votes cast on election day. Not one ballot was marked wrong which is a fine showing with so many new voters and a great credit to the ladies.” (Nov. 10, 1920, p. 2) The landslide victory of Harding and Coolidge over Democrats Cox and Roosevelt rated huge front-page headlines from the Enterprise on November 3, 1920. In the following weeks, the paper mentioned more civics lectures sponsored by women’s clubs and organizational details about the League of Women Voters and the Women’s Auxiliary of the Foreign Legion. In Maynard, there was talk of running a woman for the school board and forming a Parent-Teachers’ association. There was obviously plenty of work needed to achieve the goals of improving living conditions, fostering equality, and protecting children; they would not happen magically because women could vote. When the Nineteenth Amendment officially became law on August 26, 1920, it was a milestone that was achieved after decades of struggle. Its importance should not be underestimated. At the same time, it has to be recognized that suffrage was not universal, given restrictions on who was considered a citizen and who was allowed to be registered to vote. The work did not end that day. --------------------------------- *All newspaper references here are to issues of the Concord Enterprise that at the time covered Concord, Concord Junction, the four Acton villages, Maynard, Sudbury and sometimes Bedford and Marlborough. Sometimes a seemingly identical paper was published as the Acton Enterprise. Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed