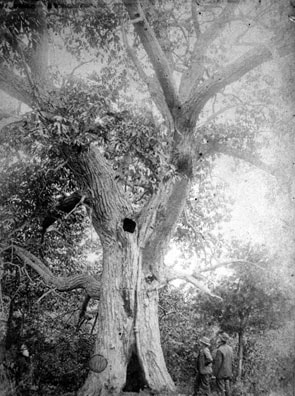

Original picture was found in a South Acton attic, current location unknown. AHS has photograph of original. Original picture was found in a South Acton attic, current location unknown. AHS has photograph of original. The Society’s collection includes a copy of a picture of two men and a woman looking up at an ancient tree that is believed to have been located on the Hapgood property in East Acton. All traces of the tree are long-gone. In former days, however, the tree was quite well-known. James Fletcher’s Acton in History (pages 279-280) described it as “one of the original settlers of the town,” thriving when Captain Isaac Davis and Acton’s company of minutemen passed by on their way to Concord’s North Bridge in April, 1775. Thoreau, who had a great appreciation for old trees, apparently was well-acquainted with the Hapgood chestnut. We have yet to find a mention of it in Thoreau’s writings, but Emerson wrote in his journal on 6 August 1849 that he and Thoreau had walked to Acton the day before and had visited a big chestnut tree on Strawberry Hill. That jaunt was apparently not Thoreau’s only visit. According to local historians, townspeople referred to the tree as “Thoreau’s Chestnut” because of his habit of stopping there. Thoreau was definitely back on the Hapgood land to do surveying in 1853; his woodlot survey is held at Concord Public Library. Fletcher’s History tells us that Thoreau visited the old chestnut tree with his sister and measured the trunk at twenty-two feet in circumference. The Thoreau siblings’ visit must have been before May, 1862 when Thoreau died. The tree continued to grow and, no doubt, attracted more visitors. In his 1890 History, Fletcher wrote: “The interior of the tree is hollow. The cavity is circular, sixty inches in diameter and twenty-five feet in height, through which one may look and see the sky beyond. An opening has recently been cut at the bottom and entrance can be easily made. There are worse places for a night’s lodging. A good crop of chestnuts is yearly produced by its living branches. The town should get possession of this luscious tablet of the bygones and see that no ruthless axe take it too soon from the eyes of the present generation.” Our photograph matches Fletcher’s description of a large tree, hollow inside, with an opening at the bottom and a hole up high, through which one could presumably see the sky. The fact that Fletcher wrote that an opening had been cut at the bottom “recently” might indicate that the picture was taken in the late 1880s-1890, but it is possible that a gap had existed previously and simply had been enlarged. Our picture shows three people observing the tree; we have not been able to prove their identities. Despite the tree’s local fame, its end seems to have been unrecorded in town reports and the local newspaper. The chestnut may have succumbed to a “ruthless axe” or to the devasting effect of the chestnut blight in the early twentieth century. The chestnut blight, a fungus that destroys the trees above ground and makes it impossible for young trees to mature, was discovered in New York in 1904. Believed to have been imported on nursery stock, it started spreading, reaching Massachusetts some years later. We searched the Concord Enterprise for news of local chestnuts. At first, the few mentions of chestnuts involved “normal” activity and concerns. For example, in 1907, West Acton lumber dealer Arthur Blanchard sent his portable sawmill operation to South Sudbury to harvest two lots of chestnut that he had purchased. (Jan. 2, 1907, p. 1) That fall, Arthur M. Whitcomb was making barrels with chestnut staves in the old overall shop in West Acton. (Sept. 18, 1907, p.5) In October 1911, Maynard landowners were complaining that young trespassers, senselessly shooting at small birds, were damaging chestnut trees; “the terrible abuse which the trees are subjected to are simply ruining them and very soon there will be few decent chestnut trees about here if a stop is not put to this practice.” (Oct. 25, 1911, p. 3) The landowners were, possibly accidentally, quite prescient; spores of the blight-causing fungus found entry through wounds in chestnut trees’ bark. The Boston Herald (Jan. 21, 1912, Sunday Magazine, p. 1) reported on the spread of the chestnut fungus and the experience of other states. At that point, the blight had started to show up in Massachusetts, particularly on the Connecticut border. Historically, the chestnut had been admired by and useful to the people in its range, providing wood products, abundant nuts in the fall, and shade. By the time the blight was discovered, chestnut trees, naturally rot-resistant, were the primary local source of telephone poles and railroad ties. They were also used by furniture makers, carpenters, and tanneries (an important Massachusetts industry). Ecologically, the loss of the chestnut was even worse, as it was also a major source of food for wildlife. (For more information about the blight, see a Report by the Forest Service.) Despite the ecological and economic damage caused by the fungus, there was little mention of it in Acton sources as the blight spread. The town’s annual Tree Warden reports made no mention of the loss of chestnuts or of the blight during the whole 1904-1940 period. This could be because farmers, fruit growers, and landowners were coping with the arrival of brown-tailed and gypsy moths, San Jose Scale, and the elm leaf beetle. It could also be that most of Acton’s American chestnuts had already been cut down. Turning back to the Concord Enterprise for news of local chestnuts, we learned that they did not all go at once. In November, 1916, children headed out from the West Acton Baptist church “chestnutting” in the towns of Boxboro, Harvard and Stow. The report was that they were not very successful in their hunt, but they had a good time playing hide and seek. (Nov. 1, 1916, p. 10) In December of that year, the Enterprise started mentioning the blight in general terms. (Dec. 20, 1916, p.2) Two months later, it was noted that people were “cutting down the forests at a fearful rate” and that disease and insect pests, including the chestnut blight, were causing great harm. (Feb. 21, 1917, p. 2) In April, 1917, the paper discussed the white pine blister rust that appeared set to destroy the pine forests, an extremely alarming prospect for Massachusetts, though it was believed that the rust could be stopped much more easily than chestnut blight. (April 18, 1917, p. 7) In 1919, the local paper reported that farther west in Massachusetts, a town was so hard-hit that townspeople believed that all the “old spread” chestnuts would be gone within three years. (March 19, 1919, p. 4) On Oct. 22, 1919, the Enterprise finally commented directly on the fate of local chestnuts, saying that the blight seemed to be destroying them and that there was no known way to combat it. (p. 2) As the destruction of chestnut trees began to seem inevitable, experts urged landowners to cut down the trees before they were too far deteriorated to be of economic use. We do not know if that was the fate of Thoreau’s Chestnut or not. We do know that its owner Benjamin Hapgood died in 1920, and his farm was auctioned off in 1923. An ad for the auction advertised, among many other items, a “lot of Chestnut 2x4 and 2x6.” Where the lumber came from, we have no way of knowing. (Enterprise, Nov. 14, 1923, p. 1) Whatever happened to Thoreau’s Chestnut, it is clear that only a few recorded memories are left. If you have pictures or stories about it, or if you can help us to confirm the identity of the people and the tree in our picture, we would love to hear from you. Please contact us. Comments are closed.

|

Acton Historical Society

Discoveries, stories, and a few mysteries from our society's archives. CategoriesAll Acton Town History Arts Business & Industry Family History Items In Collection Military & Veteran Photographs Recreation & Clubs Schools |

Quick Links

|

Open Hours

Jenks Library:

Please contact us for an appointment or to ask your research questions. Hosmer House Museum: Open for special events. |

Contact

|

Copyright © 2024 Acton Historical Society, All Rights Reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed