|

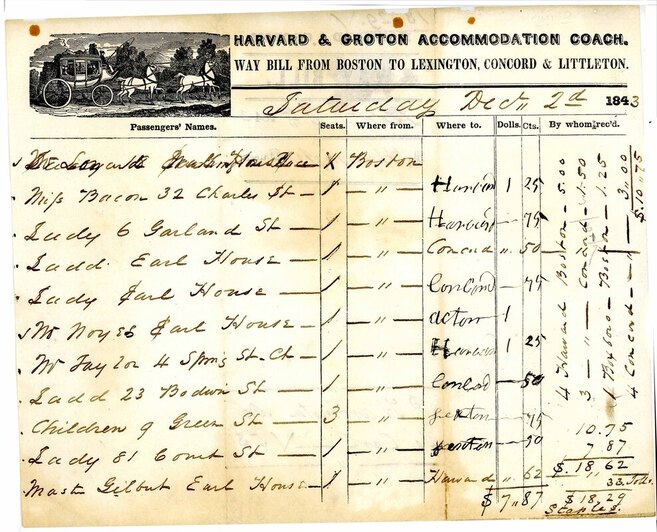

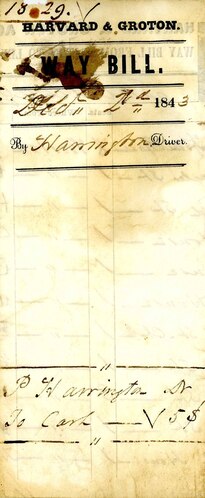

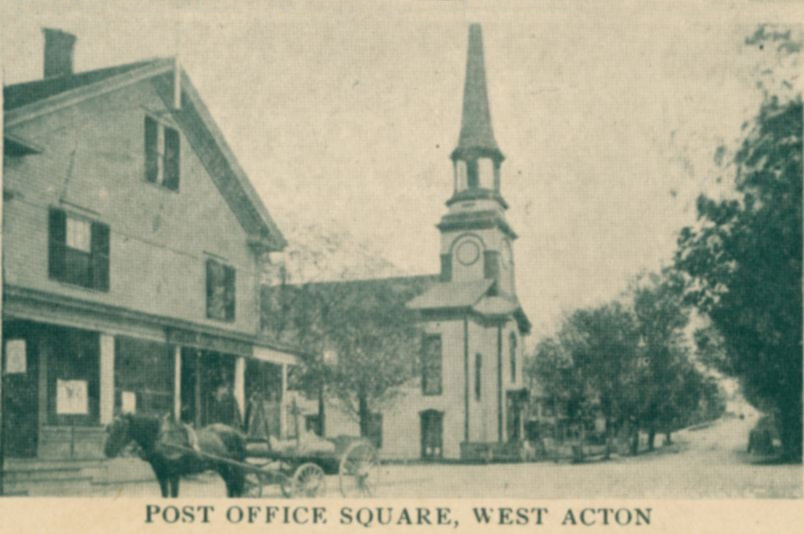

4/24/2023 Stagecoaches Through ActonOur document collection contains a way bill listing passengers who rode a stagecoach from Boston on Saturday, Dec. 2, 1843. Among the passengers was Mr. Noyes who caught the coach at “Earl House” and headed to Acton. The document is a souvenir of travel just before Acton’s transportation choices changed dramatically. Prior to the arrival of the Fitchburg Railroad in 1844, as Fletcher’s Acton in History tells us, travel to and from Boston “was slow and difficult. The country trader’s merchandise had to be hauled by means of ox or horse-teams from the city. Lines of stage-coaches indeed radiated in all directions from the city for the conveyance of passengers, but so much time was consumed in going and returning by this conveyance that a stop over night was absolutely necessary if any business was to be done. ... a visit to Boston before the era of the railroad was something to be planned as a matter of serious concern. All the internal commerce between city and country necessitated stage-coaches and teams of every description, and on all the main lines of road might be seen long lines of four and eight-horse teams conveying merchandise to and from the city. As a matter of necessity, taverns and hostelries were numerous and generally well patronized.” (p. 268) Coaches required fresh teams of horses at intervals, so stops were usually made every 8-12 miles. Acton had taverns before the stage routes (for example Mark White’s at 274 Great Road and Jones Tavern in South Acton), but as stage travel became more prevalent, taverns and inns multiplied as well. Shattuck’s History of Concord says that the first public stagecoaches came from Boston “into the country through Concord, in 1791, by Messrs. John Vose & Co.” (p. 205) Ads for stages between Boston “and the country north-west thereof” were being advertised in the Columbian Centinel in 1793, leaving from Charlestown and passing through Concord and Groton. Acton was not mentioned specifically, but presumably stages traveled via today’s Great Road, coming from Concord, through East Acton, by Nagog Pond, and on into Littleton. That route was noted as “Littleton Road” on a map drawn by Jabez Brown in 1794 and was also in early days referred to as the Groton Road. Like later decisions about railroad routes, decisions made elsewhere about stage and mail routes would have significant effects on businesses in outlying towns. The Columbian Centinel ran a series of proposals in 1794 that indicated that the mail route from Boston to Keene and other points in New Hampshire had not yet been settled. It would either go through Concord and Lancaster or Concord and Groton. Later, there seem to have been disputes among “interested persons” such as innkeepers about whether there was a significant difference in distance between the Groton-to-Lexington routes via Carlisle or Concord. (Green’s Historical Sketch, p. 193) By June 1810, the Boston Patriot was running ads for competing stage lines that explicitly mentioned Acton. Luther Carlton advertised the Concord, Harvard & Winchendon Stage that left Boston on Wednesdays & Saturdays at 7 a.m., passing through West Cambridge, Lexington, Concord, Acton, Boxborough, Harvard, Shirley, Lunenburg, and Fitchburg. (On Saturdays, it continued on to Ashburnham and Winchendon.) Return trips were on Mondays and Fridays. (June 23, p. 4) Meanwhile, a “new Arrangement of the old Concord and Leominster MAIL STAGE” was leaving Boston on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays at 5 a.m. going through Cambridge, West Cambridge, Lexington, North Lincoln, Concord, South Acton, Stow, Bolton, Lancaster, Leominster, South Fitchburg, Westminster, Gardner, Templeton, Gerry and Athol. The return stage left Athol at 4 a.m. on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, arriving in Boston in the evening. The latter ad noted that the meal stop was at the Hotel in Concord. (June 2, p. 4) On March 16, 1827, the Boston Traveler advertised that the Boston and Keene Union Stage Company ran a daily stage line leaving Boston at 5 a. m., passing through Lexington, Concord, Acton, Groton, Townsend, Ashby, Rindge (NH), Fitzwilliam (NH), Troy (NH), and Keene (NH), arriving at 5 p.m. in Charlestown (NH). Connections from Keene and Charlestown allowed travelers to continue on to points in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Saratoga Springs. “The Company have been to great expense in purchasing the best of horses and carriages and employing the most careful and obliging drivers, and have spared no pains in establishing the line that it shall not be exceeded by any other from Boston for dispatch and convenience of passengers. They have fourteen changes of teams between Boston and Charlestown, giving only about eight miles for each set of horses.” (p. 3) Stage coach stops such as those advertised by the Union Stage Company encouraged the growth of taverns and inns. Fletcher tells us that “in the east part of Acton, on the road leading from Boston to Keene, there were no less than four or five houses of public entertainment.” (p. 268) An 1831 map shows “Weatherbee’s” (65 Great Road), “Hatgood’s” (really Hapgood’s at 162 Great Road) and White’s (514 Great Road) taverns along Groton Road. The earlier White’s Tavern had been opened in 1755 and operated for a number of years, but it was not in operation in 1831. Fletcher’s History also notes that additional demand for taverns was from drovers who would accompany livestock to their summering pastures in New Hampshire. Wetherbee’s Tavern was well-known to drovers and drivers of baggage-wagons all the way to Canada. (Fletcher, p. 294)  Hosmer Tavern, 471 Mass. Ave., c. 1930s-1940s Hosmer Tavern, 471 Mass. Ave., c. 1930s-1940s Another stage route through Acton followed the Union Turnpike, although as originally surveyed, it had some steep grades farther west that were not popular with stage coach drivers. During the cash-strapped post-Revolutionary War years, the expansion of long-distance roads was often accomplished by for-profit ventures that would involve building a road and then collecting tolls, often at bridges. The Union Turnpike was approved by the Massachusetts Legislature in March 1804 and started operating in 1809. Joel Hosmer of Acton, seeing a business opportunity, enlarged his father’s house at 471 Massachusetts Avenue along the Union Turnpike route to serve as a tavern. (Joel Hosmer appears as one of the names attached to the Union Turnpike Corporation in the legislative act that established it.) The History of Harvard tells us that once Harvard got its own post office around 1811, the Harvard, Lunenburg and Winchendon stage would come with mail and passengers from Concord over the Union Turnpike. Those coaches would stop at a tavern in Harvard (the half-way point) for meals. Hosmer’s Tavern, like the Turnpike itself, was not a profitable venture. The Union Turnpike’s competitor route, the Lancaster and Bolton Turnpike, had easier grades. After the Union Turnpike’s bridge in Harvard was swept away by flooding in 1818, it was not rebuilt. The overly-steep grades were eventually abandoned and what was left of the turnpike in Middlesex County became a public road in 1830. Today, Acton’s Massachusetts Avenue (Route 111) follows the route of the old turnpike. During the 1830s, changes in transportation were happening elsewhere, but coaches kept running through Acton. The Daily Evening Transcript on Sept. 2, 1833 advertised the Lunenburg & Boston Mail Stage, leaving Boston on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays at 8 a. m., arriving in Lunenburg at 4 p.m., passing through Cambridge, Concord, Acton, Harvard, Still River Village, Shirley Village, and Shirley. One could buy tickets at Brigham’s, 42 Hanover Street, from proprietor William Shepherd. The Bay State Democrat ran an ad on June 3, 1840 for a new line of post coaches to Harvard, MA that would go from 9 Court Street, Boston, via Cambridge, West Cambridge, Lexington, Bedford, Concord, Acton and Boxboro on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. The Worcester Palladium advertised on March 31, 1841 proposed (presumably mail) routes, for two-horse coaches. The first was from Concord to Shirley by way of Acton, Boxboro and Harvard, 18 miles in four hours (Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, to leave at 2 p.m.). The return trip was to leave Shirley on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 7 a.m. The second route was from Worcester to Lowell, going through Boylston, Berlin, Feltonville, Stow, Acton and Chelmsford. We found no further information on the latter route. In terms of time and place, the ad most relevant to our way bill was found in the March 24, 1843 Boston Traveler. U.S. Mail Coaches would start out from Boston at 10 A. M., leaving from the office at 9 Court Street and 36 Hanover Street on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays for Lexington, Concord, Acton, Boxboro, Harvard, Shirley Village and Leominster Village. The return trip was from Harvard at 9 A. M. Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Our way bill was a Saturday run with 12 passengers (including some children). Mr. Noyes left for Acton from Earl House, listed in the 1842 Boston Almanac as Earl’s Coffee House, operating at 36 Hanover Street. The driver, P. Harrington, may have been Phineas Harrington who, according to Samuel A. Green’s Groton history, had a long career as a stage coach driver in the area. By the time Mr. Noyes took his trip to Acton in Dec. 1843, transportation patterns were changing. Railroads were already providing an alternative to stagecoaches elsewhere. The Fitchburg Railroad was completed to West Acton in the autumn of 1844, and Fletcher says, “that village became a distributing point for the delivery of goods destined for more remote points.” (p. 268) An ad from the Boston Courier on Oct. 28, 1844 tells us that “down trains” to Charlestown would leave West Acton at 7:36 and 10:51 am and around 5 p.m. Trains from Charlestown would leave at 8 a.m. and 1 and 4:30 p.m. After the 8 a.m. train arrived in Acton, stages would leave from there every day except Sunday for “Littleton, Groton, Townsend, Lunenburg, Fitchburg, Ashburnham, Winchendon, Westminster, South Gardner, Templeton, Phillipston, Athol, Mass.; Fitzwilliam, Troy, Swansey, Keene, Walpole, Charlestown, N. H.; Chester, Windsor, Woodstock, Rutland, Middlebury, Royalton, Montpelier, and Burlington, Vt.” There were other stages that only traveled three days per week for points in western Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, as well as Albany, NY. After the first train arrived in Acton just after 11 a.m., stages would leave for “Stow, Boxboro’, Bolton, Harvard, Lancaster, Leominster and Fitchburg” on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, and for Littleton and Groton on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. As the railroad was extended and lines proliferated, transportation patterns changed rapidly. Both South and West Acton kept growing thanks to the railroad, but Acton was only a stage hub for so many other destinations for a short time. Eventually, stagecoaches became a thing of the past. We are lucky to have in our archives a tangible reminder of those earlier days. Sources:

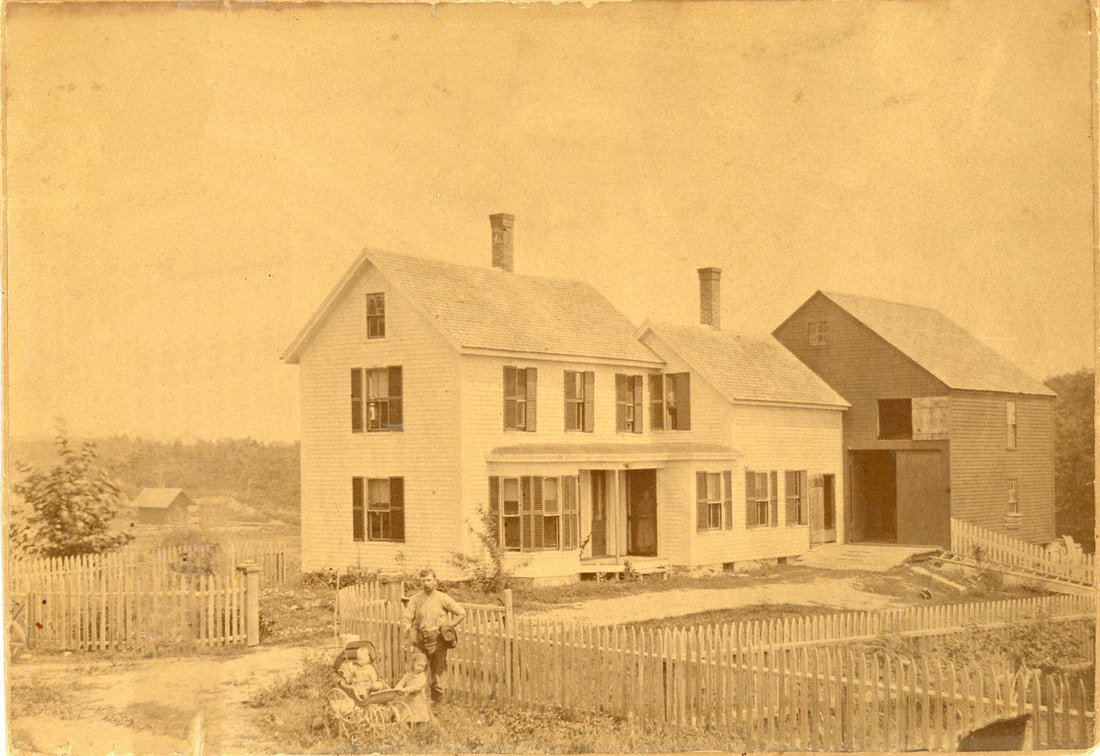

We are also grateful to the following websites for sharing information and sources on stage routes in other towns (all accessed April 23, 2023): Ella Miller’s five-year diaries at our Society give us an idea of what life was like for a career Acton schoolteacher at the beginning of the twentieth century. An issue that Ella mentioned often was the complications she faced in getting to and from work. As mentioned in our previous blog post, Ella’s earliest teaching job would have presented few commuting problems. After graduation from Framingham Normal School in the spring of 1896, she started teaching that fall in the same schoolhouse that she had attended in North Acton around the corner from her home. Ella’s time teaching in North Acton was the end of an era. One-room schoolhouses were being consolidated into larger schools. In the fall of 1899, Ella and the students from North Acton were sent to the “Centre” school on Meetinghouse Hill, following the East Acton school that had been closed in 1897. Southeastern Acton students were sent to the South Acton school the year before that. The idea behind the consolidations was that they would improve students’ educational experience by reducing the number of grades a teacher needed to handle. Ella became teacher of the Center school’s intermediate students, with grades 4-6 in her classroom. The move to the Center School, while it may have reduced Ella’s in-classroom complications, added complexity to her travels to and from her North Acton home. The distance was a little less than two miles, by today’s standards a miraculously short commute. In Ella’s day, those miles could be a challenge. Though she lived near train tracks, the trains, even if they came through at the right time, did not go to Acton center. Ella, who would at the diaries’ beginning have been dressed in a long skirt and wearing a corset, found various ways to get to her job. There were days in all seasons when she would walk, either because of nice weather or lack of other options. On some days, she bicycled, and on others, her father gave her a ride in a horse-drawn vehicle. Without weather forecasts, there would have been plenty of room for error. On some days, she optimistically took her “wheel” to school, only to be faced with rain in the afternoon. Even if her father hitched up a horse and took her to work, there were factors to consider. Was there mud, ice, or snow to deal with? Occasionally Ella would mention that the conditions were “so slippery and horse smooth” that the going was extremely difficult; the horse’s shoes had to match road conditions. There was also an important decision to make about whether to take a wheeled vehicle or use “runners” for going over snow. Once choices were made, occasional mishaps were inevitable. In Jan. 1909, she reported that she had gone to school in the sleigh, but the going was rough. On one memorable day in Feb. 1911, a man who sometimes worked on the Miller farm took Ella in the sleigh. En route, “a runner broke & lowered my side to the ground. Came back and went in the wagon.” The following day, the sleigh went to the blacksmith’s shop. The Millers put their “democrat” wagon on runners, and after that it was “fine sleighing.” As snow receded, road conditions were variable and a real challenge. She walked home on Feb. 26 and 27, 1914 and said “Rather hard walking because snow is getting soft & makes it slumpy.” Then came mud season. On March 8, 1912, Ella wrote “Getting muddy but snow lingers in patches, slippery in shady places on the road.” On March 31, 1918, she wrote “A bad mud spot for autos just north of the house. Pa had to help Mr. Park of Chelmsford out with the horse & warned others.” The following March, Ella noted that there was “an auto stuck in the mud for 2 hours out here toward dusk.” Sometimes, other people made the roads even worse. In December 1914, Ella noted that “The trucks carrying Halls’ logs are making bad work of the roads, especially down beyond Hollowells”. When, finally, the roads dried up, Ella could ride her bicycle to school. Ella would note in her diary when she took her first spring ride. Not surprisingly, she would occasionally have issues with her bicycle. The second day of school in September 1908, her pedal came off, and there were inevitable problems with wheels and tires. Her neighbor Elmer Cheney often helped her with repairs, putting in a new valve or adding “Neverleak” to a tire. Sometimes if it rained after school, she would ride home anyway. She was a hardy person, but even she mentioned at the end of October 1914 that she’d gotten chilled coming home on her bicycle. (There was a little snow that morning, and it reached 33 degrees at night). She must have been particularly determined (or desperate) on Dec. 2, 1918 when she rode her bicycle at 16 degrees. The one option that Ella had for public transportation was to take the “barge” that the town provided for students from outlying areas to get to school. The barge was horse-drawn and provided (some) protection from the weather. Ella seems to have made a practice of taking the barge only when it was particularly needed. She mentioned conditions that induced her to take the barge; muddy roads, rain, thunder and high wind, sub-zero temperatures, a major snowstorm, and her family horse being lame. On May 11, 1917 she wrote that she “came home in barge every night, partly because of ironing, cooking, weather & Aunt Eliza being here.” Riding the barge was not a perfect commuting solution. The barge drivers had the same issues with deciding between wheels and runners as did the Millers. Some days were tough going. Children’s absences were often blamed on late barges, but Ella couldn’t afford to be late. On March 6, 1923, Ella reported that the “East Acton school barge tipped over yesterday morning on the way to school and several children had slight bruises.” There were also occasional behavioral incidents during the trips. On Feb. 8, 1912, Superintendent Hill came to school at Ella’s request to talk with a student “about his immoral language in the barge.” On December 15, 1921, Ella reported “Trouble in the North Acton barge going home last night – Boys pounding Kathleen so she didn’t come to school.” That incident led to another superintendent’s visit. By the 1910s, some people in Ella’s acquaintance had bought automobiles. Superintendents in early days covered multiple towns. In 1910, superintendent Frank Hill supervised Acton, Littleton and Westford. The 1911 reorganization of the district to include Carlisle seems to have become too much, and Mr. Hill started making his trek by auto. In April 1915, Ella’s co-teacher and friend Martha Smith got an automobile. In the later 1910s, Ella would sometimes get rides get rides from Miss Smith and others. Over the years of Ella’s diaries, it is interesting to note that while some, like the Smiths, started traveling by auto, the horse remained the means of transportation for many. As late as January 1926, Ella noted that it was icy for autos that morning, so “Pa got horse sharpened.” Even though cars would have solved many commuting problems, they added their own as well. In 1917, Ella mentioned that “Miss Smith wrenched her back cranking auto last night. Feeling mean but came to school.” (Mean was Ella’s term for sick or sore.) On two other occasions, Ella mentioned men breaking an arm while cranking their automobiles. Other teachers had their own commuting issues. Those who were living in other towns might rely on trains. Ella noted in Dec. 1917 that Miss Barrett had not gotten to school until 9 o’clock because her train was late and she missed the barge at East Acton. Ella’s father picked her up with horse power. Miss Durkee, an hour late in March 1920, had resorted to snowshoes to get to school. Whatever the mode of transportation, the condition of the roads mattered. Ella occasionally mentioned men working on the road, macadamizing (putting down gravel) or tarring. Snow clearing was a perpetual problem. In Feb. 1920, a storm dropped so much snow that men including Ella’s father shoveled the road by hand to make it wide enough for an auto. Later that week, Ella mentioned her father shoveling the North Acton driveway where drifts were four feet deep. A particularly memorable road issue was caused by the Freeman family in 1914. On Sept. 6, Ella reported that Mr. Freeman had bought a little house and was going to move it onto Ruth Robbins’ North Acton land. At various times in October, Ella would mention which part of the road was affected that day. On Oct. 8, Ella mentioned that it was right across the road that evening. A week later, it was half way to the brook. On the 19th, “Freeman’s house is at the brook, so we go by through the brook.” The next day, “Freeman’s house was almost at the corner so we could go around the triangle.” On Sunday the 25th, “The autos have been very thick by here today & yesterday afternoon because Freeman’s house still blocks the state road.” Presumably the house reached its destination soon thereafter, because the traffic reports stopped.  Miller Home, 32 Concord Road Miller Home, 32 Concord Road A New Commute, Twice In 1919, Ella’s mother passed away. It was time for a change. Ella bought a house just outside the center at 32 Concord Road. For a while, the family went “down home” to the farm periodically. There was a time when the property was rented, but eventually a buyer was found. The move to Concord Road would have made Ella’s commuting to the Center School considerably easier. Snowy days were still a problem, of course. In January 1923, Ella tried skiing and liked it enough to buy skis of her own. She used them occasionally to get to work on days such as Jan. 15, 1923 when it was snowing hard and the barges had difficulty getting through. She learned later that winter that skis might not be so useful for getting home if the snow had softened up. The horse-drawn school barges were replaced by school busses in the fall of 1923. In the winter of 1924 and 1925, Ella mentioned that the busses had trouble getting through snow-filled roads and brought the children over an hour late. In Jan. 1925, a bus got stuck on “Pope’s Road” and didn’t deliver the last children home until 6:30 pm. Ella never mentioned missing the old sleighs in the winter, but it might have occurred to her. Ironically, after moving closer to her work, Ella’s commute became longer again in 1926. After years of contention (see blog post), Acton finally had managed to agree to build a high school that opened up at Kelley’s corner on January 11, 1926. On March 1, 1926, the 7th grade went to that building with Ella as their teacher. Ella’s father borrowed the Smiths’ horse and took her to school that day. On the 10th and the 15th, Ella mentioned that the roads were slippery for the horse to cope with. On the 18th, a neighbor gave Pa some “never-slip” shoes for the horse that were put on by the blacksmith. Ella’s sister Loraine gave her a ride to and from work on the 16th, and that may have convinced Ella to buy her own car on the 20th, a Ford coupe (known to us as a Model T). Driving lessons followed from friends and her sister. Ella mentioned learning to back up and turn around in the field below the cemetery and practicing turning around “up on edge of Boxboro, at Mr. Tenney’s, Miss Conant’s, Taylor’s store & schoolyard.” Her father continued taking her by horsepower, but as the new school year began, on Sept. 7, 1926, Ella wrote that she began going back and forth in her own car. The freedom must have been welcome, although later entries showed that Ella started having familiar-sounding problems. As cold weather arrived, her car wouldn’t start. She got chains for her tires and needed repeated charges for her battery. Water, alcohol and glycerin were put into the radiator and taken out again. On one ride, she noticed her steering wheel wobbling badly. At other times, her foot pedals needed adjusting, and there were issues with her generator. At the beginning of the next school year she reported, “Had a new experience with the car – couldn’t start it without pushing because something locked.” That was soon followed by “Had the brakes + lights on my car tested by Harold Coughlin. One headlight was not working – a surprise to me.” In October, after a teachers’ meeting, Ella had to ask the superintendent to crank her car, not an ideal work situation. We are missing Ella’s 1928-1932 diary, so we don’t know many of the details from those years. Driving must not have been a perfect solution for Ella. We learned from the Superintendent’s annual report that Ella moved back to the Center school, “nearer her home” in the fall of 1931. A relative newcomer, the superintendent reported that “at Acton Centre all teachers are new to the building,” which must have amused Ella after her many years there. She became principal of the Center school, and Marion Towne took over the seventh grade in the high school building. By the time Ella was writing in her final diary, 1933-1935, she made a practice of not registering her car until April. She would find other ways to get to school in the winter months. (She did mention that the weather would have allowed her to take the car to school every day in January 1933 if it had been registered.) By March 1933, signs of her failing health were beginning to show. Ella, who had amazing energy in her younger days, mentioned that she was getting winded walking to and from school. Mr. Fobes started transporting her, for which she was grateful. Ella continued to drive in better weather. Two of Ella’s final diary entries related to her car. On May 16, 1935, she got an oil change and the next day she wrote “All in tonight. Managed to take car to W. Acton by appointment & left to be tested and brakes relined & for them to bring home.” Sadly, that seems to have been her last excursion. By then, her heart was apparently giving out. Her diary entries stopped on May 25, and, as her sister Loraine noted in the diary later, “Ella’s work ended” on June 4. The Centre Grammar School was closed during part of the next day so that her pupils could attend her funeral. At age 57, she had been the oldest and the longest-serving teacher in Acton. 1/20/2023 Ella Lizzie Miller, Acton DiaristAs mentioned in our previous blog post, diaries can be a wonderful source of information about Acton in former days. At the Society’s Jenks Library, we are lucky to have a set of five-year diaries starting in 1908 kept by Ella Lizzie Miller, an Acton native who spent her nearly 39-year career teaching in Acton’s schools. Miller descendants have been very generous over the years, supplying our Society not only with Ella’s diaries, but with pictures, postcards, letters, memoirs, autograph books, and other items from the Miller family’s years in town. Before delving into the diaries, it seemed worthwhile to do some background research on Ella’s early life and her family. Ella Lizzie Miller was the eldest child of Charles Isaac Miller and Lucy Elizabeth Keyes. Charles was born on Aug. 24, 1850 in Sudbury, Vermont. His father Samuel Cooley Miller died in 1852 of sepsis from a cut on his finger. The 1860 census shows Charles living with his mother, his Miller grandmother, and two siblings in Sudbury, VT. In April 1871, Charles was (supposedly temporarily) working as a brakeman for the Northern Railroad, coupling railroad cars of a freight train at Canaan, NH. His right arm got caught, and his arm had to be amputated above the elbow. Newspapers reported details of the accident but also that employees of the railroad presented him with a gift of $91.50. Charles came to North Acton in 1873, around the time that the Nashua & Acton Railroad connected to the very sparsely-populated North Acton, branching off from the Framingham and Lowell that had arrived in 1871. Charles became the North Acton depot master, also serving as telegraph operator, switchman, and signal tender. According to Phalen’s history of Acton he “was so adept at handling freight and express with (his) attached hook that he was ever a marvel to the youngsters of the town.” (page 216) In January 1876, Charles bought from Daniel Harris ten acres between the Framingham and Lowell Railroad and the main road. That July, he bought an additional thirteen acres that went from the “Road to Lowell” (approximately #737 on today’s Main Street) to the “Mill Brook” (Nashoba Brook). The Framingham and Lowell Railroad ran through the land. The thirteen acres had once belonged to Aaron Woods and had been sold at auction the year before. (Aaron Woods' unsought fame was the subject of a previous blog post.) Ella Miller’s mother was Lucy Elizabeth (“Lizzie”) Keyes, born March 22, 1856 in Westford, MA. Her father Edward Keyes had died in South Carolina in August 1865, having served in the Union army for four years. For a while, Lizzie and her mother Lucy Ann (Robinson) lived in Groton with Lizzie’s grandmother. On May 23, 1872, Lizzie’s mother married Acton’s Isaac Train Flagg. Lizzie’s half-sister Edith Flagg was born March 11, 1875, and though Edith became Ella’s aunt, she really was her contemporary. According to family records, Charles Miller married Lucy “Lizzie” Keyes on Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 30, 1876 in North Acton. Four children followed: Ella Lizzie born Sept. 26, 1877, Alice Emma born March 10, 1879, Samuel Elmore born Nov. 25, 1881, and Loraine Esther born Nov. 6, 1884. Ella and her siblings grew up on the farm with the railroad running through their land behind the house, the depot just below, and the North Acton schoolhouse around the corner. The road in front led from Acton Center to Lowell. If Ella kept diaries as a young woman, unfortunately they did not find their way to our Society. We have had to use other sources to put together her early life. She attended the white schoolhouse on what is now Harris Street. A picture from between 1888 and 1890 shows her and Blanche Varney as the oldest of the students taught in the building by Miss Jessie Jones. The Concord Enterprise gives us glimpses of Ella’s later academic career. In 1890, she was one of 22 students (only 2 from North Acton) who were admitted to the relatively new High School program. She became the managing (and inaugural) editor of the school literary magazine "The Actonian." Ella was one of five students who graduated in June 1894. At the ceremony, she was selected to give an address entitled “Oars and Sails.” Town reports show that Ella L. Miller, while a member of the high school’s senior class, served as an assistant teacher in the South Primary School in Spring 1894. The School Committee’s annual report noted that “during the spring we were obliged, by the large number of pupils in attendance, to employ an assistant teacher and this assistant was compelled to take her classes into a corner of the schoolroom or to the cloak room, or the hallway, as the weather permitted.” (page 56) The hallways presumably would not have been heated. It was certainly an introduction to teaching with constrained resources. Ella and fellow graduate Blanche Varney passed the entrance examination for Framingham Normal School, a teachers’ training college. This was particularly important because as late as the 1897-1898 school year, the Superintendent’s report noted that Acton’s high school was not approved by the State Board of Education. The 1890s were a time when the state and the towns were struggling with what constituted a legitimate high school, with issues such as the minimum number of teachers, years of study, and curriculum. Ella’s autograph book, in possession of the Society, shows that she was originally a member of the Class of 1893, but in 1893, the high school course was changed to four years, and apparently Ella was one of the few who continued on. Ella graduated from Framingham Normal School in 1896. Ella was paid for teaching the North Acton school in the fall and winter of the 1896-1897 school year, taking over after the resignation of Lillian Richardson. Ella taught there for the next two years at a salary of $10 per week. In the Fall of 1899, the North Acton school was merged into the Center school, and Ella started teaching in the new “intermediate” division there (grades 4-6). Probably as a result of her change of school, a typo in the 1900 report said that Ella was “appointed,” starting her service in Acton schools, in 1899. The error was repeated in town reports for decades. On March 17, 1897 (according to Ella’s later diaries), the family moved to Hudson where Charles bought farmland at about 181 Central Street. Charles still owned the North Acton farm, but he was trying to sell it. An ad attached to the back of a photograph owned by the Society reads: “FOR SALE - Thirteen-acre farm: fine vegetable garden: nice lot of sweet corn: asparagus and strawberry beds: good shade trees: excellent drinking water: house six rooms: barn: two henhouses: near railroad station and post office: half mile off State road from Boston to Ayer: two miles to center of town. Desirable for summer home or good location for poultry or small fruit farm. Price $3500. C. I. MILLER, North Acton." Someone wrote on the back of the picture that Charles did not find a buyer. He may have found someone else work the land in the meantime, however. Ella was teaching in North Acton, so we don’t know how she managed logistics. She might have stayed in the house or boarded with a family. Commuting that distance would not have been easy in those days, whether by horse or train. An Acton Center newspaper item in April 1903 mentioned that “Miss Loraine Miller of Hudson spent Monday with her sister, Miss Ella Miller,” giving the impression that Ella was staying in town at least some of the time. Ella’s brother Sam started working for the Boston & Maine Railroad as a telegraph operator and ticket taker in 1899 and moved to Beverly. Ella’s sister Alice married Hudson neighbor Halden L. Coolidge in May 1904 and settled down at 205 Central Street, Hudson. Neither Sam nor Alice lived in Acton after that. We do not know what precipitated Charles’ move to Hudson. His mother, who had remarried and spent many years in Wisconsin, came back to Vermont and passed away in 1895. We had hypothesized that she left him some money. However, Charles entered into various mortgage transactions in the 1900-1904 period, so he may have been feeling financially stretched. The mortgages were paid off. In October 1904, Charles transferred the thirteen-acre North Acton farm to Ella for the price of one dollar. In 1905, a buyer for the Hudson farm materialized, so Ella’s family returned to their North Acton farm late in the year. Ella taught in Acton for eleven years before our diaries begin. Unfortunately, we only have brief snippets from newspapers to show what she was doing aside from teaching during that time. The Enterprise mentioned that Ella taught a Young People’s Society of Christian Endeavor class in early 1896. In January, 1902, she hosted the Shakespeare Club. In August 1907, Ella, Martha Smith, and Sarah and Helen Wood took a vacation at York Beach, Maine (Aug. 14, 1907, p.8) Ella’s parents became involved in the Grange in Hudson. When they were moving back to Acton in late 1905, about one hundred Grange members and neighbors showed up at a sendoff at Alice’s house. Ella and her parents became involved in the formation of the Acton Grange in March 1906. In 1907, Charles and Ella were both elected to Grange positions and Ella’s mother Lizzie was sent to the state Grange meeting as Acton’s delegate. The Grange would continue to be an important part of their lives in later years. Ella’s diaries begin on January 1, 1908. Over the next few months, we plan to use them to learn more about her life and also about what Acton was like in the early years of the twentieth century. The Miller Siblings: Some references used:

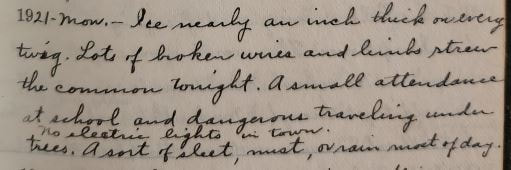

12/12/2022 Ice Storm Pictures Dated With Diary EntriesWhile we have all heard that “a picture is worth a thousand words,” those of us who deal regularly with unlabeled photographs often wish for just a few words to help us. The Society’s collections include some pictures of an ice storm that hit Acton in November a century ago. Our photographs had different years written on the backs (1921 and 1922), and we were unsure which was correct. Fortunately, diaries can be invaluable for giving first-hand information about events. In this case, Ella Miller’s diary provided the information we needed. She often wrote about the weather and mentioned no ice storm in November 1922. November 1921, however, was a different story. On November 10, 1921, Ella wrote, “Thurs. – Everything covered with ice this morning. Several wires broken in the Centre and limbs broken from trees.” One might have assumed that the November 10 ice storm was the storm in the pictures until one read more from Ella’s 1921 diary: Nov. 28: “Mon. – Ice nearly an inch thick on every twig. Lots of broken wires and limbs strew the common tonight. A small attendance at school and dangerous traveling under trees. A sort of sleet, mist, or rain most of day. No electric lights in town.” Ella's 1921 diary continues: Nov. 29: “Tues. – Still raining and freezing on & trees breaking down. The worst storm of its kind in years. No school. Mr. Edwards came to tell me he couldn’t get through & Mr. Smith turned around here with only five [students]. Pa took Aunt Emma & me down street to see the ruins.” Nov. 30: “Wed. – Sun shining and ice beginning to melt & drop off. More children at school than on Monday. Webster’s weighed one leaf covered with ice – 1 ½ lb. Have begun cleaning up the common.” Dec. 1: “Thurs. - ... Ice nearly off trees. No electric lights since Sun. night – gloomy.” We are very grateful to have photographs of Acton scenes and events at Jenks Library and, sometimes, words to explain them.

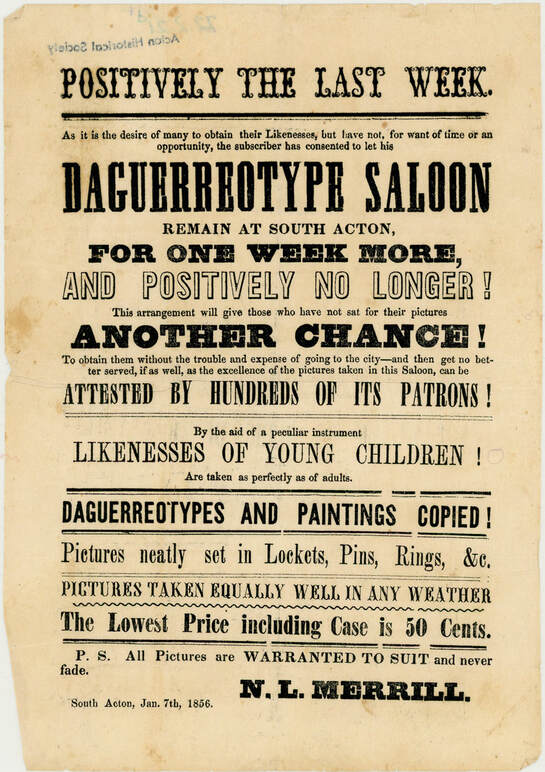

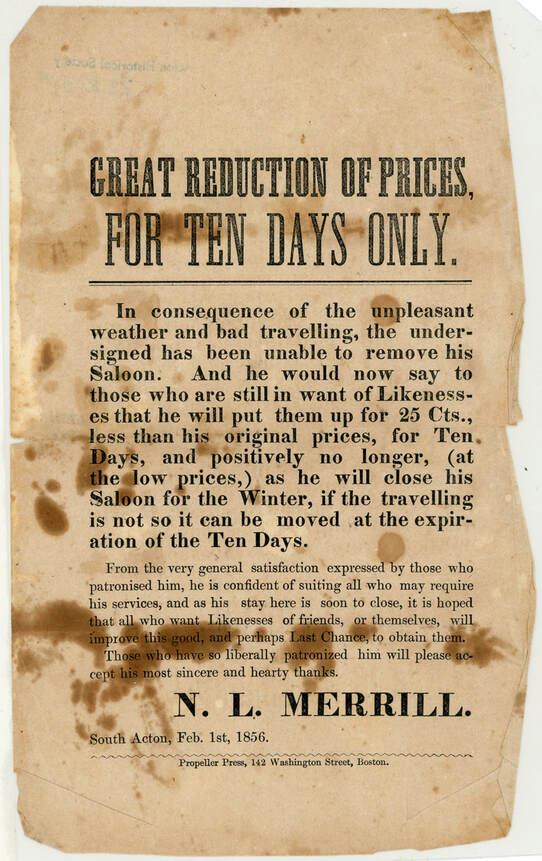

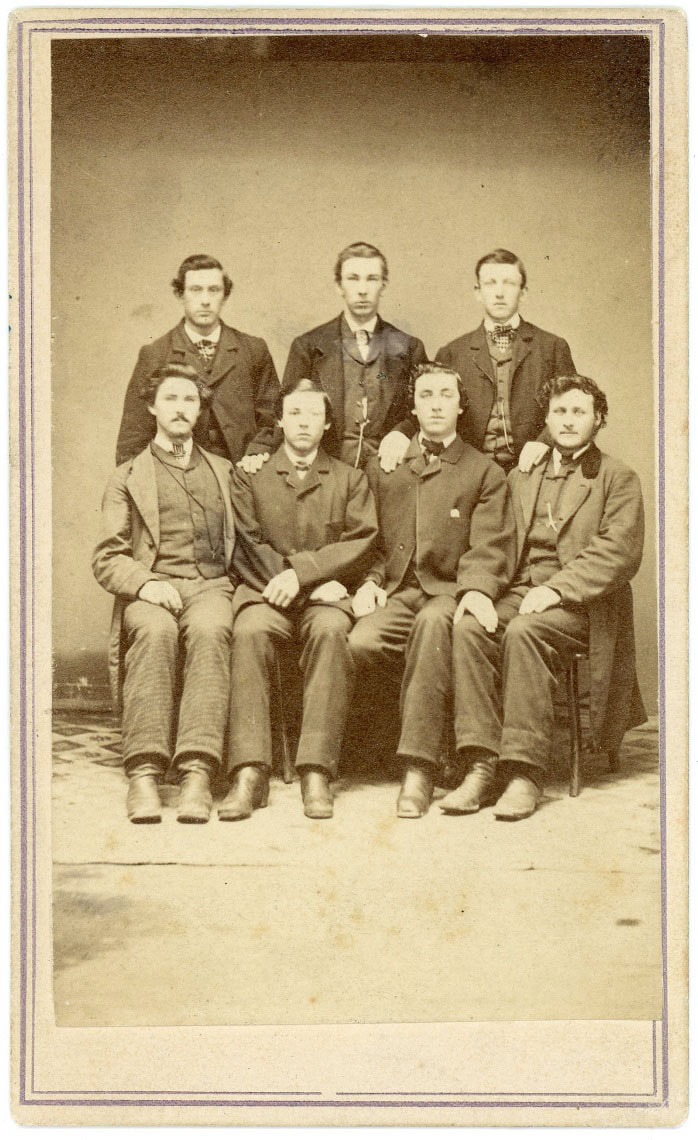

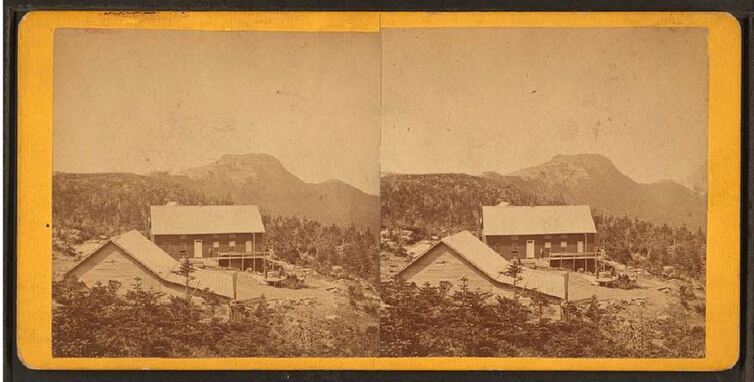

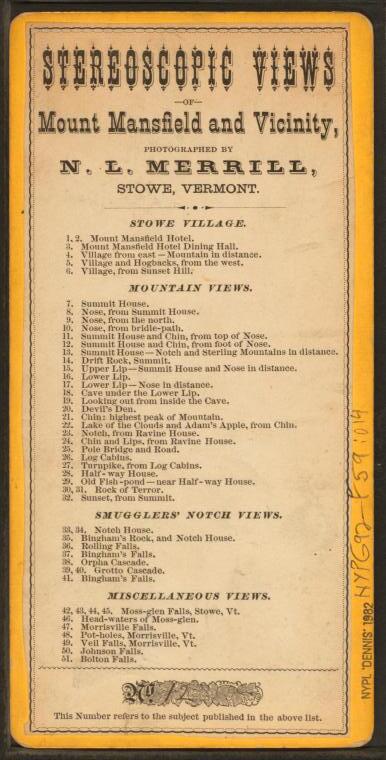

10/29/2022 A Real Diary or a School Project?In one of the scrapbooks at Jenks Library, there is a page of copied newsprint columns. The date, title, page number, and publication place of the newspaper are unknown, but the page includes, “Diary of Sarah Faulkner. Born March 18, 1756, of Colonel Francis Faulkner and Lizzie Muzzey Faulkner.” Quoted excerpts follow about events leading up to and during the American Revolution. At first glance, the page could seem to be describing a firsthand source about Acton, produced by a young woman at a critical time in its history. The account was originally indexed in our files merely as “Sarah Faulkner’s Diary,” but more investigation showed that our page came from a high school history composition completed in 1936. What struck us was how easy it would have been, if that “diary transcription” had been posted online, for someone’s imaginative exercise to spread as “fact.” Transcriptions that we find on the internet can be wonderful sources that allow us to search for topics of interest quickly and easily. Sometimes the original can be very hard to track down, but as our example shows, it is worth finding out where a transcription came from. It is especially helpful when transcriptions are accompanied by digitized versions of the original documents. For example, in Acton we are lucky to have online access to our earliest town records, both digital images and indexed and searchable transcriptions, thanks to the efforts of Acton Memorial Library and some dedicated volunteers. (Original, Transcription) Jenks Library and many other archives have extensive collections of diaries, journals, and letters, many of which have never been transcribed. While they can be frustratingly incomplete when one is looking for a specific piece of information, they are incomparable sources for understanding the actual interests and concerns of people in earlier times. A small sampling of original sources in our collection: A fascinating set of handbills in our collection advertised a photographer working in South Acton in early 1856. N. L. Merrill announced on Jan. 7th that for “positively the last week,” his Daguerreotype Saloon would be operating and could save locals from going to the city to “obtain their likeness.” Pictures could be taken regardless of the weather. Merrill could even take pictures of young children “by the aid of a peculiar instrument.” He also would copy one-of-a-kind daguerreotypes and paintings. A second flyer dated Feb. 1, 1856 stated that bad weather and travel conditions had kept his Saloon in South Acton. For an additional ten days, he would provide likenesses discounted by 25 cents, after which he would move on or close down for the winter. Who Was N. L. Merrill? Curious, we consulted Steele and Polito’s monumental work A Directory of Massachusetts Photographers 1839-1900. No N. L. Merrill was listed there. Further research yielded no one of that name operating as a photographer locally, so we had to search farther afield. The only likely candidate for the South Acton Saloon’s owner was a photographer who later operated mostly in Vermont, Nathaniel L. Merrill, usually known by his initials. Oddly, we were not able to determine exactly where he came from, how he came to be in South Acton, or where he went when the weather allowed him to move on. Though historians have written about daguerreotype studios in major cities, it is very hard to learn about pre-Civil War itinerant photographers. They would have been on the move constantly, and their advertising, by handbills passed around and probably posted somewhere in town, did not generally leave traces for researchers to follow. The fact that N. L. Merrill’s South Acton flyers were preserved long enough to end up in our archives is quite remarkable. Assuming we are correct about N. L. Merrill’s identity, we were able to learn about his later career. The search took us miles from Acton but revealed the challenges of an early photographer who repeatedly adapted to changing technology and kept moving to find new markets. Digitized records, newspapers, and photographs allowed us to discover at least some of N. L. Merrill’s travels; we suspect that there were more. The early life of N. L. Merrill was difficult to uncover. The earliest information we found was a newspaper mention that “he was an excellent artist when we knew him at Irasburgh (VT), in 1850.” (Orleans Independent Standard, April 10, 1868, p.2) It seems that he traveled with a portable studio, sometimes referred to as a “daguerreotype saloon car” or a “moveable saloon.” He would presumably stay until the customers dwindled and then move on. Apparently in the course of his travels, he met Prudentia D. Waters whom he married on Jan. 25, 1853 in Johnson, Vermont. Prudentia was born and raised in Johnson, and the couple may have considered that place their home base for at least some of their time together. Unfortunately, the marriage record gives us no information that would help either to pinpoint Nathaniel Merrill’s origins or to distinguish him from many others of the same name. The record said that he was living in Portland, Maine at the time, but a Portland directory for that year yielded no photographer N. L. Merrill. Further research in the area turned up nothing useful. The next evidence of him is the pair of 1856 handbills in our archives. The 1860 census recorded him in Nashua working as an "artist," though that is the only evidence we found of him in New Hampshire. After 1860, N. L. Merrill is much easier to find because he turned to newspaper advertising and produced paper photographs with his name and location on the mats. In March 1860, the Bellows Falls Times announced that N. L. Merrill was in town with a saloon where he was taking pictures “in a very superior manner.” The enterprising Mr. Merrill had furnished the newspaper with a copied photograph that elicited a great deal of enthusiasm from the reporter. Merrill ran ads at times in the Bellows Falls Times between the summer of 1860 and at least Feb. 1862. By now he had changed technologies and was apparently settling down for a while. He announced: "MERRILL’S PHOTOGRAPH & AMBROTYPE SALOON, SPRINGFIELD, VT. The public are invited to call and examine his specimens, the only place in this vicinity where COLORED PHOTOGRAPHS ARE TAKEN. By this process life-like pictures may be obtained from old and inferior Ambrotypes and Daguerreotypes, and warranted to give satisfaction. The negative is always preserved, and persons wishing duplicates can have them at any time by ordering. LOCATED IN THE SQUARE.” (among other ads, this ran in the Bellows Falls Times, July 20, 1860, p. 4) During the Civil War years, Nathaniel L. Merrill seems to have spent a good deal of his time in Springfield. He was there working as a “Photographist” when he registered for the draft and was taxed for a photographer’s license in the 1862-1865 period. Some of his portraits from this period have been made available online including this photograph of seven young men taken in December 1864, courtesy of Brad Purinton’s Tokens of Companionship blog: The Lamoille Newsdealer of July 12, 1865 wrote that “N. L. Merrill, from Sprin[g]field, Vt., is now stopping at Johnson for the purpose of accommodating the public with any kind of a picture known to the photographic art. He has had a large experience in the business, and will be remembered by some in this vicinity as the man who first introduced a daguerreotype car into this part of the country. – He has erected a temporary saloon, which he terms a “Camp,” on the Common near Denio’s hotel, and commenced business in it on Monday last.” (p. 3) The camp was apparently well-attended and patrons’ “urgent solicitations” led him to stay in Johnson during August as well. Around this time, N. L. Merrill seems to have bought property in Johnson. He must have sold his Springfield business, because the back of a portrait taken by J. D. Powers of Springfield, Vt., says “We have also N. L. Merrill’s Negatives in preservation, and will furnish copies when ordered.” (eBay offering, August 2022) Merrill was on the move again. He ran an ad in 1866: “Mr. N. L. Merrill, the veteran artist, has pitched his ‘camp’ near the American House in this village (Hyde Park) and will remain four weeks for the purpose of supplying the people with Photographs, Ambrotypes, and Melanotypes, of the highest perfection. Copies from old and inferior pictures can be obtained and enlarged and finished in India Ink or colors, also card Photographs for the same. A good assortment of Phot[o]graphic Frames and Albums always on hand. His reputation as an artist is well established in this vicinity. Pictures can be made in cloudy as well as fair weather.” (Lamoille Newsdealer, June 6, 1866, p. 4) N. L. Merrill moved on to Cambridge Borough, VT a few weeks later. At times, he rented rooms rather than establishing a “camp.” A woman’s portrait recently offered on eBay was marked on the back “N. L. Merrill, Photographer, Rooms over Kinsley & Bush’s Drug Store, Cambridge, VT.” In April 1868, N. L. Merrill leased a photographer’s “saloon” in Barton Landing in northeastern Vermont. He was listed in the Vermont State Directory of 1870 in Johnson, though the 1870 census shows him in Montgomery, Vermont. (The entry listed Nathan Merrill, photographer, married to “Patience.” Presumably he was passing through town and the census taker did not work too hard on the details.) N.L. Merrill also had a studio in Dunham, in the Eastern Townships of Quebec where he was listed in Lovell’s Canadian Dominion Directory in 1871. The Brome County Historical Society holds a portrait taken by him there. In 1872, N. L. Merrill seems to have had a studio in Enosburgh Falls, Vermont, from which he moved on and a different photographer set up shop. A portrait posted online showed that at some point, N. L. Merrill also took pictures in Richford, Vermont. In the early 1870s, N. L. Merrill seems to have returned to Stowe, Vermont fairly often. According to the back of a portrait available online, he set up shop in Stowe with a company name of “Mt. Mansfield Picture Gallery.” (Another photo for sale on ebay showed the same gallery with a different photographer, so he may have bought out or sold to a photographer named O. C. Barnes.) In December 1872, N. L. Merrill closed his Stowe gallery for a few weeks and went to Rouses Point, across Lake Champlain in New York. The back of a photograph recently listed on ebay confirmed that N. L. Merrill indeed took pictures in Rouses Point. Merrill was in Stowe again in October 1873 but planned to pack up soon “and go where there are more faces.” (Lamoille Newsdealer, Oct. 15, 1873, p.4) In 1874, he reappeared in Stowe In May and September when the Argus and Patriot reported that N. L. Merrill was “again prepared to make those new style photographs.” (Sept. 3, 1874, p. 3) In addition to portraits, he took a series of Stereoscopic Views of Stowe Village, Mount Mansfield, Smugglers’ Notch and a number of nearby waterfalls. An advertisement for his gallery in Churchill’s Building in Stowe mentioned that he stocked frames, albums, brackets, knobs, and cords, along with a collection of stereoscopes and stereoscopic views. Unfortunately, there was quite a bit of competition in the “view” business, so it may not have been profitable for him. We have not found that he did any other series. The New York Public Library has a stereoscope view taken by N. L. Merrill available online, and the reverse side shows his other subjects. N. L. Merrill returned to Johnson repeatedly; by the 1870s, it was clearly his home base. In Dec. 1876, N. L. Merrill of Johnson was “taking all kinds of pictures at the photographic gallery of Mrs. B. W. Fletcher” in Waterville, VT. (Burlington Weekly Free Press, Dec. 15, 1876, p. 3) An ad in the April 25, 1877 Lamoille Newsdealer announced that N. L. Merrill would keep his Johnson photographic gallery and saloon open a few weeks longer. In July 1879, Merrill did a short stint in South Troy, Vermont, but then returned to Johnson. Nathaniel, “Photographist,” Prudentia, and daughter Mary were living there at the time of the 1880 census. The two photographs below have been made available online by Special Collections at the University of Vermont's Baily/Howe Library. Both have “Merrill, Johnson” printed on the mats. They were identified on the backs with a name, hometown, and “Classmate J. S. N. S.,” referring to Johnson State Normal School; its students would have been a good source of business for a portrait photographer. We found less frequent evidence of N. L. Merrill’s activities in the 1880s, but he was still at work. He set up a studio in Enosburgh Falls, Vermont in September 1883, but he was listed in the Lamoille County Directory of 1883 and the 1887 Vermont Business Directory as a Johnson photographer. In November 1885, daughter Mary was married to Hannibal Best at the Merrill residence in Johnson. A quit-claim deed dated Nov. 14, 1888 shows that Nathaniel, his wife Prudentia, her nephew Samuel H. Waters, and his wife Juliette sold lands and tenements in Johnson. (Three mortgages had been executed on the property/properties in 1865, 1869, and 1872.) N. L. Merrill was apparently still living in Johnson, however, while taking photographs in Waterville in Sept. 1889. In Feb. 1890, the St. Albans Daily Messenger reported that N. L. Merrill, who had had a photographic business in Johnson for many years, was moving to live with his daughter and her husband Hannibal H. Best in Enosburgh Falls. The News and Citizen reported that he was dangerously ill in mid-February 1891 and that he died in Enosburgh Falls on Feb. 26, 1891. Unfortunately, we have not found a death record or full obituary for him. A burial notice in the St. Albans Messenger on March 5 said that he had been an invalid for years, but according to an advertisement in the News and Citizen, he had been working as a photographer in Johnson as late as January 1890.

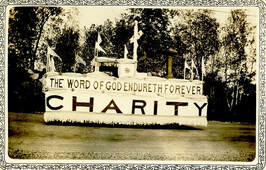

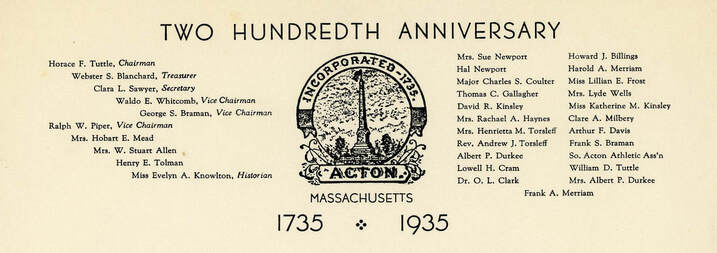

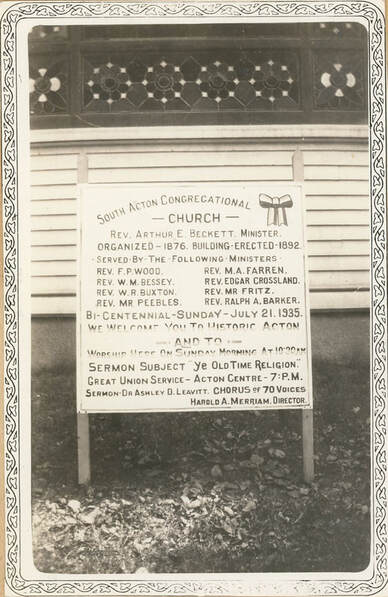

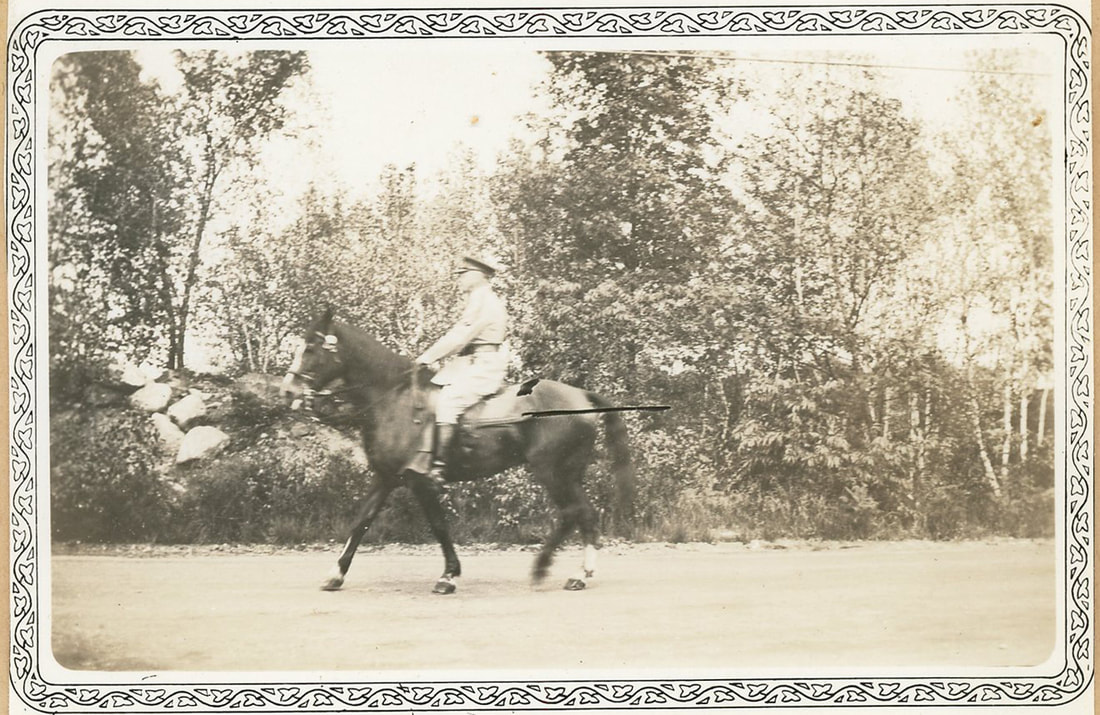

Back in Acton When we first found the flyers for N. L. Merrill’s daguerreotype saloon, we thought that he would be local and that we could easily track down his life story. What we discovered was Nathaniel L. Merrill, a Vermont photographer who had to be on the move constantly in the decades that followed 1856's saloon. We pieced together many of his movements after 1860 from digitized newspapers, records, and photographs, but we were not able to trace his origins. Different records gave his birthplace as Maine, New Hampshire or Massachusetts, and we found no source that mentioned his parents or siblings. Most of his early travels with his daguerreotype saloon in the 1850s are also unknown, including why he came to Acton (assuming our identification is correct). Any additional information would be appreciated. Clearly by 1856, the people of Acton, and South Acton in particular, could easily have had their pictures taken if they could afford it. One has to wonder what happened to the likenesses taken that winter; we would love to have scans of local pictures taken by N. L. Merrill. The Society and Iron Work Farm have rare pictures taken of local buildings lost to fire in the 1860s. They could have been Merrill’s work, or perhaps there were done by other itinerant photographers who offered their services in mid-nineteenth century Acton. It is even possible that we could have early N. L. Merrill pictures in our collection. Unlike paper photographs with mats that showed the photographer, location, and sometimes the subject of the picture, early photographs in their metal or leather cases were much harder to label. We have a collection of beautiful early portraits of unknown people done by unknown photographers; it is frustrating that no one labelled them while there was a chance of identifying them. (A selection is here.) Photography was new at the time; perhaps people simply did not imagine that eventually likenesses would survive but people’s memories would not. If your Acton ancestors’ likenesses or their photographs of local scenes are in your possession, we would be very grateful to add scans (or originals) to our collection. Please contact us. Sources Used (in addition to standard genealogical resources): 7/23/2022 A Birthday Bash with a SurpriseThe Society recently had an open house after a long period of COVID-related closure. The date was chosen for its proximity to Acton’s traditionally-celebrated “birthday,” the anniversary of its formal organization as a town on July 21, 1735. Researching how the town had marked its other birthdays, we came across a scrapbook from Acton's bicentennial celebration in 1935. The more we read, the more we appreciated how ambitious an undertaking it was for a town of 2600 people.  Gov. Curley Reviewing Parade Gov. Curley Reviewing Parade Acton’s 200th birthday was celebrated with a town-wide, three-day extravaganza. The event began at sunrise on July 20th with church bells ringing and a town crier announcing the occasion. The town was also greeted with an “unofficial” cannon salute orchestrated by Nelson Tenney. A Faulkner family reunion took place that day and brought numerous family members to the old homestead in South Acton as well as an impromptu reenactment of the activities there on April 19, 1775. The bicentennial celebration officially kicked off with a parade of military units and “motor floats” starting at 3 p. m., forming near the Faulkner House and heading to West Acton over Central Street. Participants were trucked from there to Acton Center where they were joined by civilian units west of Taylor Road on Main Street. They marched on Main Street through the center, passing the Monument where they were reviewed by dignitaries such as Massachusetts’ governor James M. Curley, ex-mayor of Boston John F. “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald and other local notables. The parade ended at the Schoolhouse on Meetinghouse Hill. After the parade, there were speeches by the politicians and a rendition of “Sweet Adelaide” sung by John F. Fitzgerald. Florence Piper Tuttle, a poet and Acton native, read “Acton Speaks,” a poem composed for the occasion. After more speeches and a supper provided by one of the women’s clubs (reports varied as to which one), there was a band concert given by an American Legion Post Band from Watertown. On Sunday morning, the churches in town observed the occasion in various ways. The South Acton Universalist church had a memorial service for Lucius Hosmer, a former member who was born on the site of the church. He became a noted composer of his time and had written a piece for the celebration that he had planned to conduct. Unfortunately, he had died unexpectedly earlier in the year. On Sunday afternoon, there were open houses at fifteen of the oldest homes in town, followed by a concert on the Common entirely devoted to the work of Lucius Hosmer. His piece “The Acton Patriots,” composed for the occasion, was one of the pieces. The orchestra was part of the Emergency Relief Administration’s music program. In the evening, there was a community service that involved the pastors of the town’s churches and a 60-person community chorus under the direction of Harold Merriam. On Monday July 22, librarian and artist Arthur F. Davis led a 50-vehicle automobile tour over the approximate route taken by Capt. Isaac Davis and his Minutemen company to Concord on April 19, 1775 and then back past the Robbins farm site where a rider had spread the news to Acton that “The Regulars are coming.” Jenks Library has copies of the annotated tour itinerary. Next on the day’s agenda was a historical pageant that involved about 10% of the town’s population, held on the Acton Fairgrounds behind town hall. The E. R. A. orchestra apparently was involved as well. The celebration wrapped up with a Military Ball on Monday evening at Exchange Hall attended by invited guests (including Honey Fitz) and about 300 couples. The Liners Broadcasting Orchestra gave a concert there at 8, followed by a Grand March. Dancing then followed until 1 a.m. One has to be impressed with the effort that Acton residents put into celebrating their town’s bicentennial. According to newspapers, they were rewarded with the attendance of large crowds, 12,000 or more showing up on Saturday and 6,000 or more for the pageant. (It is not clear how accurate the estimates were. The Herald estimated 10,000 at the pageant.) There undoubtedly were many memorable moments for the participants, but judging from newspaper articles about the weekend, the most newsworthy event happened during the parade. The parade was in three divisions. First came the grand marshal Maj. Charles S. Coulter on his horse. He was followed in an open car by first division marshal George L. Towne, the last living member of the Capt. Isaac Davis Post of the G. A. R. Next came military units, including a band from Fort Devens, followed by a long line of army trucks that were used to transport marchers from West Acton to Acton Center to finish the parade. The second division was led by its marshal Lowell Cram and the Watertown American Legion band that drew particular attention because of its “girl drum major,” evidently a surprising sight at the time. Following them were about thirty decorated floats from Acton civic and other organizations such as the American Legion Auxiliary, Boy Scouts, Woman’s Clubs, Odd Fellows and Winona Rebekans, Grange, and the Concord Reformatory. The third division seems to have been made up of local, civilian and veteran marchers and horse-drawn vehicles.  West Acton Baptist Church float West Acton Baptist Church float Governor Curley and the others reviewing the parade by the Monument had just seen the Center fire company go by. They were then able to see, five hundred yards away, a float farther back in the parade going up in flames. One can imagine the chaotic scene as the firemen took their chemical apparatus and raced back past the other marchers “with sirens screeching and bells clanging” to fight the fire. Reports mentioned that hundreds headed toward the excitement, necessitating a good deal of crowd control by local police and American Legion members helping out. The burning float represented the West Acton Baptist church. A sturdy framework had been built on top of and all around a truck owned by Jesse Briggs. The framework was then decorated with religious messages and flags. The float featured a pulpit displaying an antique Bible from the church. Driving the truck was the church’s organist, Alden Johnson, accompanied by the truck owner’s son Russell. When the engine caught fire in front of Horace Tuttle’s house on Main Street, Mr. Johnson pulled over. The doors being blocked, both men had to climb out of the truck’s windows and jump to safety. The firefighters were on the scene quickly, but they had a hard time getting to the engine fire, as the float was so well built that it took time to rip it apart. Somehow, the items on the float that belonged to the church made their way safely into the hands of its pastor, and no one was injured. The truck, however, had a very bad day. The importance of the bicentennial celebration to the townspeople who took part is evidenced by the large number of related items that were carefully saved and eventually donated to the Society. We have programs, articles describing the events, souvenirs, pins, photographs including three copies of a panoramic picture of the pageant’s participants, pageant dialogue written by Evelyn Knowlton, clothing worn in the pageant, a telegram sharing the news that one of the expected speakers was hospitalized, and letters from invited dignitaries who did not attend. Among the pictures, there is even one of the church float before its demise. Newspaper photographers were on hand to capture the firemen at work, their pictures accompanying articles with headlines such as “Two Jump from Blazing Float,” “Two Men Leap from Burning Float During Spectacular Parade in Acton,” and “Men Narrowly Escape Flames as Decorated Truck Bursts Forth in Fire at Height of Great Bi-Centennial Celebration with Governor as Guest.” The Boston Herald may have referred to “the little town of Acton, almost forgotten but sturdy and proud” (July 14, 1935, p.6), but those who attended the parade seem to have found Acton quite memorable. A Selection of Items in the Society's Collection: Sources Available Online: