|

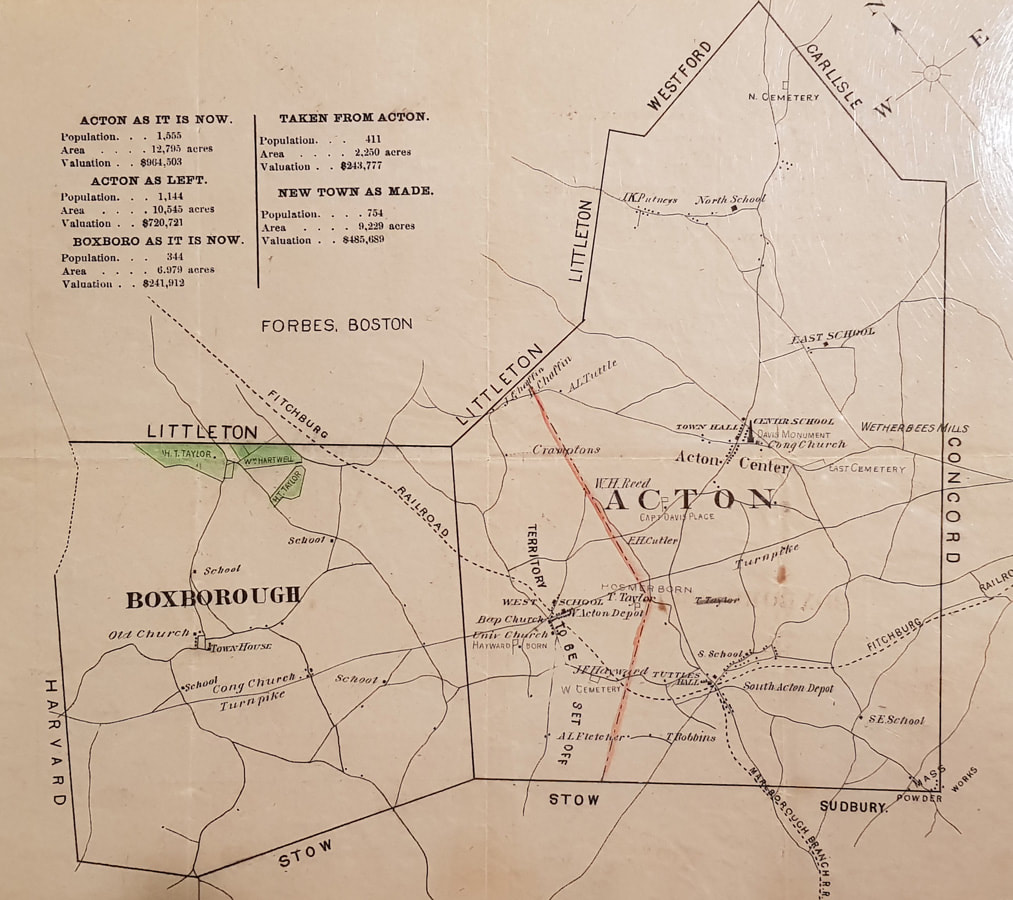

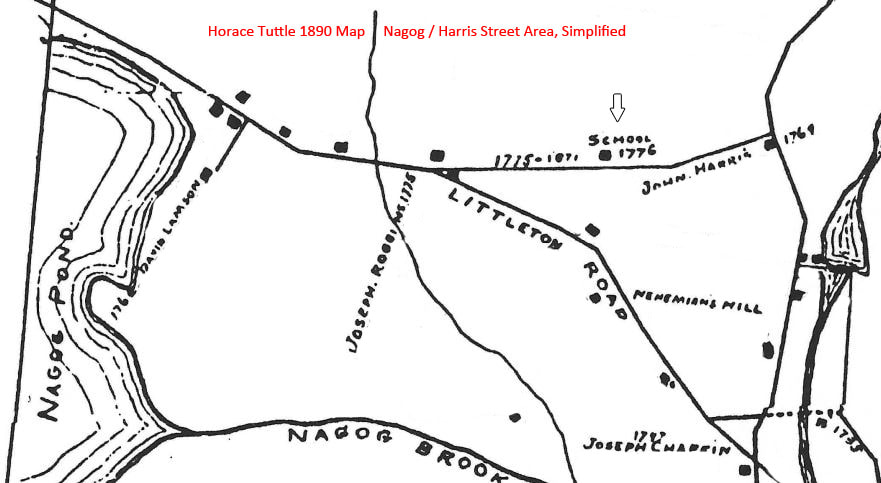

2/23/2021 West Acton Tried to SecedeIn our collection are two maps of Acton and Boxborough with a red outline around part of Acton, dating back to 1868-1869. At that time, residents of the western part of Acton were proposing to secede and join with Boxborough in creating a new town. Shown with the maps are the two towns’ relative populations, areas, and tax valuations, and how those would change if the proposal passed. The new town would take 26% of Acton’s population, 18% of its area, and 25% of its tax valuation. Previous local historians have puzzled over this village uprising (see references), but recently the Society was fortunate to be given access to a memoir from George C. Wright that discussed the West Acton secession proposal from the perspective of someone involved. Having access to digitized newspapers from the time added other details to the story. Decisions over the exact route of railroads and the location of depots led to changes in the relative fortunes of many towns and villages in the 1800s. Some boomed while others were passed by. To Boxborough residents in the 1860s, this was an issue of great importance. After failing to get a depot of their own, Boxborough residents generally went to West Acton to send their produce to market or to get to the city themselves. For most of Boxborough’s inhabitants, the nearest store was in West Acton. The central issue from Boxborough’s perspective was that the railroad had changed West Acton’s fortunes for the better. Boxborough residents were helping it to thrive, and they wanted some of the tax benefits. Underlying some of the agitation was probably the fact that businessmen with Boxborough roots had moved to West Acton, prospered, and contributed to the growth of their adopted village. George C. Wright wrote that about the time that the railroad came through in the 1840s, there was a small “boom” in West Acton, a place that had previously barely had enough economic activity to be called a village. (p.2) Though South Acton eclipsed it as a center of industry and mercantile activity, West Acton certainly grew as a result of the railroad. While presumably Boxborough’s farmers profited personally from having a railroad nearby to take their goods to wider markets, one can understand that they wanted the benefits for their town that they saw accruing to their neighbors each time they headed east on the turnpike. The actors in the secession drama seem to vary depending upon who was telling the story. The petition to the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives of Massachusetts, published by the town of Littleton, stated that the 57 signers were a mix of Boxborough and Acton citizens. However, after tracing each signer, we were able to find a Boxborough listing in the 1870 census or other evidence of Boxborough residence for 50 of them (plus another whose name was probably misspelled). Two signers had lived in both Boxborough and Acton, and four signers’ residence eluded us. Absent from the petition are the names of the quite well-known businessmen of West Acton with roots in Boxborough, among them West Acton Meads and Blanchards, and George C. Wright (who spent his teenage years in Boxborough). According to Phalen’s History of the Town of Acton, the petition’s supporters were the majority of the people of Boxborough and “the disgruntled minority” of Acton citizens who were trying to create a town “cut to their own pattern” that, by weight of numbers, they would be able to dominate. Phalen said, “The coterie in West Acton that started the scheme was motivated by no altruistic notions with respect to the established families of old Boxborough.... Very shortly the rural community would have found itself perpetually out-voted and more or less ignored except as an expansion area for its vigorous and ambitious new bedfellow.” (p. 203-204) Based on the published list of petitioners and Phalen’s history, we might have thought that the proposed new town was really a “Boxborough issue” with the support of a few West Acton outsiders. However, George C. Wright’s version of events contradicts that conclusion. George C. Wright and West Acton’s Boxborough natives were extremely generous to West Acton and did much for its development. (See our blog post on George C. Wright.) Over the long haul, they did not come across as the disgruntled “coterie” that Phalen described. Nonetheless, apparently George C. Wright not only approved, but was a leader of the secession effort. He wrote that the proposal was backed by “a large majority of the citizens of West Acton,” including native Boxborough businessmen, and that “I was heartily in favor of the project and was chairman of the committee to secure the necessary action by the legislature. I did everything I could to carry the measure through, sparing neither time or money...” (p. 6) Town meeting records from Acton show that the proposed secession of West Acton had been discussed at the November 3, 1868 town meeting. The citizens of Acton as a whole disapproved. The vote was 204 to 45 in favor of a resolution that included the following statements:

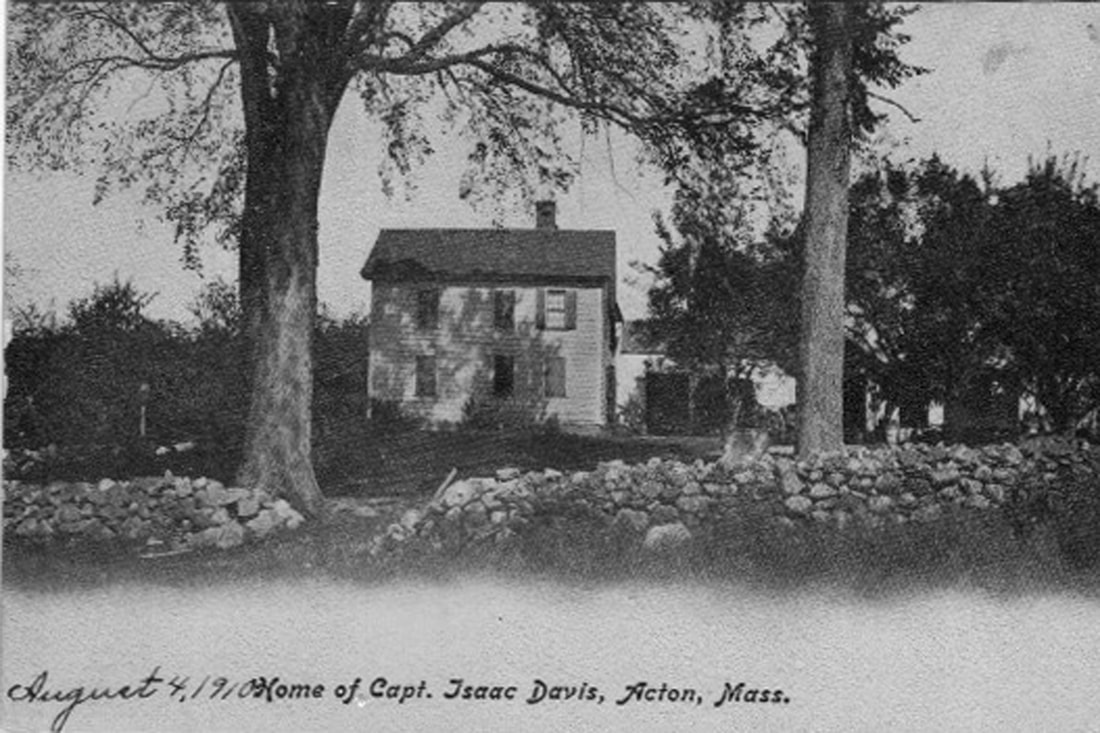

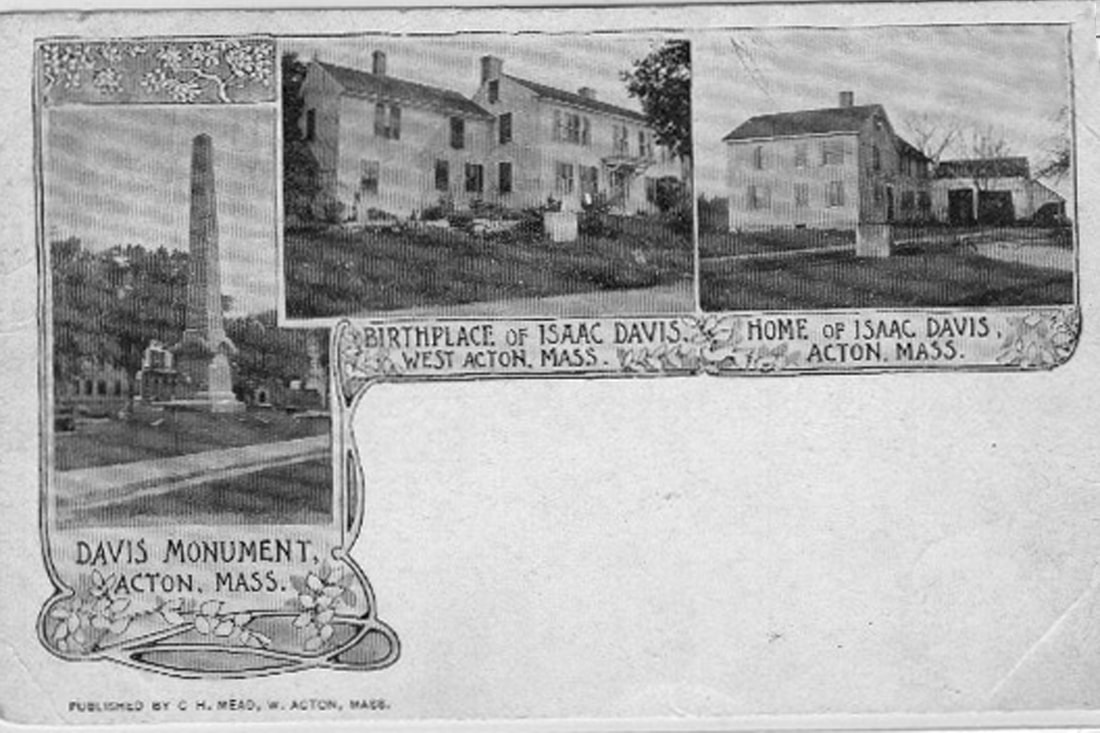

The town then chose a Committee of seven “to save the town from prospective trouble and ruin.” They were authorized to hire counsel at the expense of the town of Acton. The chosen committee members were Luther Conant, William W. Davis, John Fletcher Jr., George Gardner, Aaron C. Handley, William D. Tuttle, and Daniel Wetherbee. Apparently undeterred by opposition from the rest of the town of Acton, the proponents of the proposal moved forward. Both sides hired lawyers. On January 18, 1869, the petition to create a new town (officially known as the petition from “H. E. Felch and others” ) was referred from the Massachusetts House of Representatives and Senate to the (joint) Committee on Towns. (The Committee was surprisingly busy with other proposals as well; disagreements over territory were not unique to Boxborough and Acton. In fact, Boxborough and Littleton had their own disagreement before the Committee in 1868 and 1869, illustrated by the green-shaded properties on our maps.) The Acton committee against the proposal apparently got busy gathering signatures. Between January 27 and Feb. 2, “remonstrances” were presented by lawyers and referred to the Committee on Towns. The remonstrances were labelled with the name of the first signer “and others”, so we know that five anti-secession remonstrances were filed from Acton with the first signers being W. E. Faulkner, Daniel Wetherbee, Luther Conant, Lewis F. Ball, and George Gardner. (The latter was ”George Gardner and 18 others of West Acton” according to the Boston Herald, Feb. 3, p. 1.) On Feb. 2, there was also a remonstrance from Simeon Wetherbee and 22 others of Boxborough. According to the final report of the Committee on Towns (in our archives), the total number of remonstrants was 313. Those in favor of the petition also obtained more signatures. On Feb. 8, the Journal of the House shows that “Mr. Fay of Concord presented the petition of Wm. Reed and others of Acton and Boxborough, in aid of the petition of H. E. Felch and others.” (p. 103) Non-resident owners of real estate in Boxborough signed a petition in favor of the new town that was presented on Feb. 10 (“Henry Fowler and Others”). The total number in favor mentioned in the final report of the Committee on Towns was “about one hundred and forty or fifty petitioners.” (p. 2) The number is surprisingly vague, given the fact that the opposition signatures were counted exactly. Signing was obviously not considered enough; many supporters and opponents attended the hearings. The Springfield Republican reported that at some point during the proceedings, the Blue Room “was crowded almost to suffocation by Acton and Boxboro people.” (Feb.20, 1869, p. 2) In this midst of the petitioning and remonstrating, a call apparently went out for funding and naming the new town. A correspondent signing as “Maxwell” wrote to the Lowell Courier (Jan. 13, 1869, p. 2): When the petition is granted and the new town is born, it is reported, should some gentleman wish to have the town named for him, his wish can and will be granted should his name be acceptable to the people and his bequest or donation, to the town, be a million or some considerably less. We learn that a gentleman residing not far from Shirley and Groton Junction stands ready to give his hundreds, if not thousands, to have the town take his name. Clearly there were rumors about the possible naming of the new town. Local historians have tried to determine what the name might have been. Phalen stated that no records mentioned a new name, although he had heard a “legend” the name would have been Bromfield. (p. 203-4) Local historians in the 1990s-2010 era accessed the memory of a couple of descendants of long-time local families who thought that the name was to have been Blanchardville. Given later Blanchards’ generosity to both towns, this was a plausible name. However, with the advantage of access to digitized newspapers of the 1860s, we investigated what was said in the 1868-69 period. We did not find contemporary mentions of Blanchardville (except for a village of that name in Hampden County, MA), but we did find in the Boston Traveler of Feb. 13, 1869 (p. 4) a report on the Boxboro’ and West Acton case that mentioned “the proposed new town of Bromfield.” The Springfield Republican (Feb. 20, p. 2) confirmed that the name was “Bromfield.” The Lowell Courier of Feb. 26 (p. 3) reported on the “very lively and interesting” set of hearings held on the new town of “Bramfield.” It also stated that the petitioners from Boxborough suggested that “such annexation would increase the value of their real estate by giving them a local habitation and a name, particularly the latter.” The implication seems to be that there was money to be gained from the new name, but whether there was actually a Mr. Bromfield (or Bramfield) “ready to give his hundreds, if not thousands,” we have not discovered. Newspapers were also helpful in describing the progress of the proposal. The Boston Journal reported that the Committee on Towns took up the petition on Monday Feb. 1, 1869 and planned to visit the towns in question the following Friday. Boxborough was nearly unanimously in support of the proposal while 4/5 of West Acton supported it. (Feb. 2, p. 2) The Lowell Courier, seemingly with an opinion on the matter, reported that “Nearly all the people of both places are in favor of the union. Some opposition will be made by the town of Acton, which, however, will have left in case of division a territory larger than that of the new town, and nearly double the number of inhabitants.” (Feb. 3, 1869, p. 2) On Tuesday Feb. 9, the Committee on Towns held an early hearing on the matter. “Nearly all the legal voters of Boxboro were present, quite depopulating the town.” (Boston Herald, Feb. 9, p. 4) The arguments centered on the growth of West Acton since the building of the Fitchburg railroad and that “many of the people of Boxboro had removed thence to get the advantages of the railroad, and all of their business and other interests centered about that locality. The opposition to the project comes from the town of Acton, the people of West Acton and of Boxboro being united in favor of it.” (Boston Herald, Feb. 9, p. 4) On Feb. 10, the Boston Post (p. 3) reported that the hearing continued, but the Post’s only other comment was that “Several witnesses were called. Their testimony is not of general interest.” Fortunately, The Lowell Courier (Feb. 26, p. 3) filled in more of the arguments. In addition to Boxborough’s assertions, West Acton petitioners claimed that the new town would benefit them economically. (Their plan seems to have been that the town hall and business of the new town would be located in West Acton.) Notably, there was no claim that the town of Acton had treated them badly in the past. On the other side, the anti-petitioners from Boxborough wanted to leave their town as it was, quiet and peaceable. They feared that any benefits of the arrangement would go to West Acton, which would dominate them numerically. Acton’s opposition included “all but three of the legal voters outside of the territory proposed to be set off, with nineteen living on the territory”. Among their objections, the Courier noted that the section to be taken from Acton included some of the town’s best farming land. The result would be an awkwardly-shaped, narrow town with, they feared, decreased property values, increased taxes, and impairment to their schools. “Why, they ask, should they be impoverished that others may be enriched?” Other arguments listed in the final report of the Committee on Towns were the fact that Acton had just recently built “a large and commodious town hall,” that they had paid to build and repair roads that would now be part of another town, that having a smaller population would defer for even longer the hope of a high school in the town, and that this could set a precedent for South Acton that might seek its own alliance with the thriving village of Assabet. (p. 3) George C. Wright’s memoir added: [A] strong opposer was the late Dea. Silas Hosmer, one of our own citizens. Dea. Hosmer went before the Committee on towns with a carefully prepared paper opposing the proposed dismemberment of the town of Acton, and the point which seemed to carry the most weight with the committee was his statement that every patriot, whose bones are in the Davis monument, was born in the part of Acton which it was proposed to set off for a new town, and two of the three men went from homes in West Acton to die for their country on April 19, 1775, so that, if the proposed measure should be carried through, there would appear an anomalous state of things, namely, the situation of an imposing monument in one town in honor of men belonging to another town. (p.6) The legislators no doubt would have been reminded that much of the monument’s cost had been funded by the Commonwealth. George C. Wright also mentioned that “Among the influences which worked against us, one was found in George Parker, Esq., a member of the legislature, who was a native of Acton and a son-in-law of Rev. J. T. Woodbury. Mr. Parker’s opposition was very earnest and effective.” (p. 6) Rev. Woodbury had been the driving force behind getting the grant for the monument. (Research indicates that George Gedney Parker, born in Acton to Asa and Ann M. Parker, married Augusta Woodbury. In 1869, he was a lawyer in Milford, MA. He had not yet been elected to the legislature, but another of Rev. Woodbury’s Milford lawyer sons-in-law, Thomas G. Kent, was actually part of the Committee on Towns.) The closing arguments to the petition debate were made to the Committee on Towns on the morning of February 13. Lawyers for the opposition, Hon. David H. Mason of Newton and Samuel W. Butler, Esq. made the arguments, including an apparently eloquent recap of Silas Hosmer’s objections. Also mentioned was the “fact that the village of West Acton, by its numerical superiority, would control the proposed new town of Bromfield, and that not the slightest necessity was shown for the change, or for breaking across old town lines.” (Boston Traveler, Feb. 13, p. 4) Lawyers for the petitioners, George M. Brooks and George Heywood of Concord, spent 1-2 hours making their case that Boxborough needed help to stop its decline, that Boxborough and West Acton would benefit from the plan, and that the evidence for making a change “came from the best men in West Acton and in Boxboro’.” (Boston Traveler, Feb. 13, p. 4) The next week, the Committee on Towns held a private meeting. The result was its report of February 18, 1869 in which “with all but entire unanimity” the Committee found that though the town of Boxborough was indeed too small, if the petition were granted, both the new town and Acton would be too small. The committee was unconvinced that the new town would grow, having “no water power and no manufacturing interest well established.” (p. 4) They foresaw future political problems with a town “center” situated so far from the western boundary of the new town. Overall, the petitioners had not proved that the formation of a new town was best for the “public good.” In fact, they added: ...rather than cripple Acton in her enterprise or encroach upon her historic limits for the benefit of [Boxborough], as her inhabitants have no desire to retain their name and distinct organization, it will be an easy task to so apportion her territory to other towns as to benefit all and injure none; but with this matter the Committee are not asked and do not desire to interfere. (p. 4-5) Boxborough’s willingness to give up its identity ended up working against the proposal. It is very likely that many residents of Boxborough over the years have looked back on the decision as a fortuitous one for their town in the long run. Boxborough has maintained its identity and grown its own way. Proponent George C. Wright, looking back in his later years, had this to say from the perspective of his decades in West Acton: The result was we were defeated, and as time has passed, I have come to feel that it is just as well our measure failed to be a success. In these last years, the town of Acton has done everything for us as a village that we could reasonably ask to have done. References (in addition to newspaper articles cited in the text):

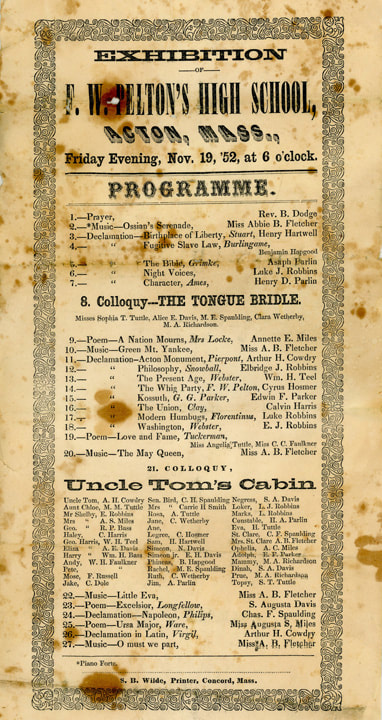

In the years before Acton had a high school of its own, students wanting to further their education needed to take opportunities where they could be found. In Acton’s early days, young men were usually the ones to seek education beyond the schoolhouse; they might be given advanced training or prepared for college by a learned individual, often the town’s minister. In the 1800s, more opportunities arose for young men and young women; some might board at private academies or, as time went on, commute to a nearby high school. In the early 1850s, Acton’s advanced students had the option of studying for short periods at a privately-run advanced school. Our Society’s collection includes a program for an exhibition of F. W. Pelton’s High School in the center district of Acton, starting at 6 p.m. on November 19, 1852. It must have been a long evening; there were twenty-seven items on the agenda, including two dramatic pieces. The Exhibition As evidence of what was going on in the minds of young Actonians in 1852, the “programme” is a revealing document. Even in a small town, there was obvious interest in the issues affecting the country as a whole. Abolition was the foremost theme of the evening. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, though now criticized because of its racial stereotypes, was hugely influential in raising awareness of the evils of slavery. It had been serialized starting in June 1851 but had only been out in book form since March 1852. An early performance in Acton, featuring over 30 performers, would have been a notable event. The song “Little Eva” that followed the performance was based on the book and had recently been published in Boston. Other items on the program that involved the issue of slavery were “declamations” on Anson Burlingame’s opposition to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, Grimke’s “Bible”, presumably Angelina Grimke’s “Appeal to the Christian Women of the South” (1836), and Henry Clay’s attempts to save “The Union” without war. Other declamations had as their subjects Daniel Webster’s writings on Washington and on “The Present Age,” Lajos Kossuth, a Hungarian leader whose words had managed to catch the popular imagination in the United States, Napoleon, and the Whig Party (written by the schoolmaster himself). We were not able to identify all of the items performed. Ames’ “Character” may have referred to one of Fisher Ames’ writings, but there is not enough information to be sure. Stuart’s “Birthplace of Liberty” and Snowball’s philosophy were similarly hard to pin down. In online searching, some of the titles are now overshadowed by later writings and events. A search for Snowball’s “Philosophy” led to many references to George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Searching for “A Nation Mourns” brought up references to Lincoln’s assassination, and “Modern Humbugs” yielded P. T. Barnum’s book The Humbugs of the World, both dating from the 1860s. (“Modern Humbugs” by Florentinus may have been a tongue-in-cheek piece written by the schoolmaster; see the section on him below.) Drama, songs, and poetry were easier to find. “The Tongue Bridle” was a dramatic piece for “four older girls” published in Boston in 1851. Thanks to the Library of Congress’ Music Division, we were able to find the 1849 Ossian’s Serenade, the 1851 Oh, Must We Part to Meet No More?, and The Green Mt. Yankee, a Temperance Medley, published in Boston in 1852. Once we had navigated past references to Led Zepplin songs, we were able to find an 1848 song by I. B. Woodbury that set Tennyson’s poem "The May Queen" to music. Henry Theodore Tuckerman’s “Love and Fame,” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1841 “Excelsior,” and Henry Ware, Jr.’s “To the Ursa Major” can all be found in online poetry collections. The only item with a strictly Acton theme was Pierpont’s poem “Acton Monument.” One wonders if the entire poem describing the events of April 18-19, 1775 was recited; even at its debut, the audience became impatient with its length. Rev. John Pierpont of Medford presented the poem at the celebration of the completion of Acton’s Monument in 1851. The reverend had the misfortune that day of being slated to recite after an hour-long address by Governor George S. Boutwell and just before the meal was served. Hungry attendees started eating during his recital of the poem, and the clatter of utensils clashed with the sound of the reverend’s voice. Apparently, he got quite upset. Acton’s Rev. Woodbury, who could have tried to quiet the crowd, instead said a quick grace and let the dinner officially begin. Boutwell’s Reminiscences quote Woodbury as telling the poet, “They listened very well, ‘till you got to Greece. They didn’t care anything about Greece.” (page 130) By that point in the day’s speeches, the audience might have been losing enthusiasm for Acton as well. Later, obviously having calmed down, Rev. Pierpont commented on the situation that “Poets at dinners must learn to be brief, Or their tongues will be beaten by cold tongue of beef.” [Boston Evening Transcript, Oct. 30, 1851, p.1) The audience at Pelton’s High School Exhibition had to have been tired by the end of the evening. After speeches, songs, poetry, and drama, Arthur Cowdrey capped off the event with a declamation in Latin from Virgil. Presumably this was to wow the audience. (Clearly, Mr. Pelton was able to teach his students a range of subjects.) Miss A. B. Fletcher performed her fourth musical number, and the evening was finished. Acton’s Private High Schools

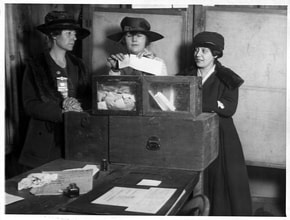

We had thought that perhaps F. W. Pelton’s high school was unique to him. However, a speech by one of his former students explained that Acton’s private high school, at least for a time, was an annual occurrence taken on by a college student during a break from his studies. It allowed a college student to earn funds and benefited the townspeople by supplementing their publicly-funded education. Eben H. Davis told Acton’s high school graduates in 1895 that: “When I was a boy, the only high school in the town was a private enterprise, held but a few weeks in the fall, in the centre of the town, and kept by some college student to eke out his college expenses. There was no orderly course of studies, but each student selected such branches as his fancy dictated or friends advised, for which he paid his own tuition. In this way it was possible to obtain a smattering of Latin or Greek, an introduction to the elements of science, and some knowledge of mathematics. But, in order to fit for college, I had to attend an academy, one hundred and fifty miles from home. ... I would by no means speak lightly of the schools of my boyhood days... Nor were those brief terms of high school studies without influence. They opened up to us new lines of thought, and the personality of the teachers, fresh from college and imbued with zeal for a higher education, made a strong impress. It was through contact with such influences that I was inspired with an ambition to go to college.” (Town Report 1896, p. 83-84) Contrary to what we had expected, this high school was not simply for older students who had progressed beyond the curriculum of Acton’s schoolhouses. Some of the students were fairly young. From reading school committee reports of the time, we discovered that the public schools in the early 1850s had a summer term and a winter term; the private school in autumn obviously filled a gap, not just of higher learning, but in a time of the year when scholars would not have been able to continue their studies. We have not yet found all of the college students who led a private autumn high school in Acton, but we did find mention of a Mr. Cutler who seems to have run a popular private school in the fall of 1848. The school committee report of 1848-1849 alludes to the difficulties of a Winter Term teacher, Dartmouth College graduate Mr. Whittier, who had come with great recommendations. “Mr. Whittier, in assuming the duties of his school, was somewhat in the position of the poor king who followed the people’s favorite, when nature’s poet said, ‘As when a well graced actor leaves the stage, All eyes are idly bent on him that enters next.’ Mr. Cutler in his select school had won all hearts, both of parents and children, and they thought his like would never appear again. This feeling among the leading scholars was a great injury to the school, which ought to have been one of the best.” We will set aside research into Mr. Cutler’s identity for another day. If anyone knows more about him or other Acton private school teachers, please let us know. The 1852 Schoolmaster, F. W. Pelton We know very little about F. W. Pelton’s brief time in Acton. We were able to identify him because the 1853 school committee report mentioned hiring F. W. Pelton “of Union College” to teach the Centre School in the winter term 1853 after he had run a private school in Acton Center in the fall of 1852. The mention of Union College allowed us to confirm that he was Florentine Whitfield Pelton, born in Somers, CT on April 23,1828 to Asa and Lois Pelton. According to Jeremiah M. Pelton’s Genealogy of the Pelton Family in America (page 477-478), Florentine Pelton left home at a young age, supposedly taught in New Jersey, and furthered his studies at Wesleyan Academy in Wilbraham, MA and Union College. The year in which F. W. Pelton taught in Acton was an unusual one. At town meeting the previous April, Acton had elected a School Committee of three clergymen. All three had left town by the end of the year. (One was Rev. J. T. Woodbury, discussed in a previous blog post.) Ebenezer Davis and Herman H. Bowers wrote the subsequent School Committee report. Two of Ebenezer Davis’ children had attended Pelton’s fall High School. F. W. Pelton’s winter term at the public school seems to have been much less successful than his private school experience. (School committees in the nineteenth century could be merciless in their reports, and teachers had no ability to present their viewpoint.) It is likely that having 52 students of varying ages, with an average attendance of 44, was a contributing factor, as well as the fact that the curriculum would not have been driven by students’ interests as it was in the private school. Pelton may already have been in career transition during his Acton period. He soon made the law his career, studying with C. R. Train and at Harvard Law. He was admitted to the Middlesex County bar in 1855, and practiced first in Marlborough and then in Boston. He married twice, first to Laura M. Buck, a graduate of the State Normal School at Framingham, MA, on Dec. 18, 1855. The couple had two children before Laura died from complications of childbirth in 1860 in Newton where they were living at the time. Pelton married Mary Reed Whitney in Waltham, MA on Nov. 20, 1862, and the couple had eight more children. In addition to practicing law, Pelton dealt in real estate and was responsible for the construction of a number of houses in Dorchester, MA. Toward the end of his life, he retired from the law, focusing on various business ventures. He settled in Dedham, MA where he died of “chronic peritonitis,” probably a complication of his diabetes, on June 25, 1885 in Dedham. We found no reference to Florentine W. Pelton’s time in Acton in newspapers, family histories, or obituaries. However, his experience there may have led to this thought from the report of the Newton Grammar School Sub-Committee, of which F. W. Pelton was a member in the 1860s: ”If the varied, difficult and exhausting work of the school-room could be understood at home, there would be more sympathy and less fault-finding with the teacher.” (Annual Report, Mass. Board of Education, Vol. 27, 1864, p. 92) Indeed. The Exhibition Participants There are many names on Pelton’s 1852 Programme, but there were only a few that we could not track down. Perhaps those students were not residents of Acton; the school committee report of 1853 mentioned that some private school scholars in the past had come from out of town. (p. 5) In the rest of the cases, we found individuals who would have been between twelve and eighteen in the fall of 1852. Among the sources we used were school committee reports; it is not surprising to find that young scholars who were enrolled in an extra school in the fall of 1852 were also commended for excellent attendance at the public schools. As best we can reconstruct it, the following is our list of Pelton’s high school exhibition participants: 8/26/2020 Finally, Acton Women Could VoteIn August 1920, the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote in the United States. Looking back from today’s perspective, one would expect the event to have been celebrated in the local paper, the Concord Enterprise, with a front page announcement and large headlines.* In fact, the reporting was subtle enough that it was not clear from the paper when the key event actually took place. The September 1 Enterprise did present a table on page six that broke down the states’ votes, classifying them by political party. Among the twenty-eight “Republican” states that had ratified the amendment were Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. The “Democratic” ratifying states were Arkansas, Arizona, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas, Utah, and finally Tennessee. Connecticut, Vermont, Florida and North Carolina had not yet made a decision, and seven states had rejected the amendment. (The Enterprise missed Oregon in its listing, so the totals did not actually add up to the necessary 36 states for ratification.)  Courtesy Library of Congress Courtesy Library of Congress It had been a long, difficult slog to get the vote. Women had to overcome a widespread belief that they were incapable of understanding important issues and of thinking for themselves. They also had to deal with opposition to the idea of women venturing out of their allotted “sphere.” Two examples from previous years’ Enterprise columns illustrate what women were up against. During the 1895 Massachusetts campaign to allow women to vote in local elections, a letter appeared in opposition that stated that “... women, by the very nature of their being, their social and domestic duties, do not and cannot have a practical knowledge of the wants or needs of a large town or city. ... their political action will be governed by their prejudices...” (Oct. 24, 1895, p. 4) This opinion elicited a rebuttal that said in part “It is surprising that in this age of advancement and higher education of women, a man of average intelligence can be found bold enough to affix his signature to an article so foreign to reason and justice.” (Oct. 31, 1895, p. 4) The South Acton writer of the rebuttal clearly overestimated the open-mindedness of the time. Twenty years later, the Enterprise said in a supposedly fair-minded editorial: “There are a great many deep thinking, intelligent men who honestly oppose suffrage for they believe the success of the movement in this state would project women into a sphere for the activities of which they are totally unfitted. They believe that the ideal balance maintained in the home would be destroyed and that no great good could be obtained through doubling the voting strength of the state.” (Oct. 27, 1915, p. 2) World War 1 changed some attitudes. Among the many ways in which women contributed during the war, women (including Acton’s Lillian Frost) went overseas to work as nurses, ambulance drivers, telephone operators, and in other support roles. The June 18, 1919 Enterprise mentioned that at least 184 nurses had died as a result. (p. 6) One week later, Massachusetts became the eighth state to ratify the nineteenth amendment. No large headlines celebrated that event. However, on July 2, 1919, the Enterprise editorialized that “with the advent of equal suffrage there will be a betterment of living conditions, greater equality, and protection of the rising generations. There will be a cleaning-up of many filthy places, and a wiping out of the sore-spots that have disgraced the nation.” (p. 2) Clearly, when the women were finally able to vote in 1920, they had many expectations to deal with, some negative and others dauntingly optimistic. Once women’s suffrage looked poised to win, the Enterprise reported on efforts to ensure the success of women’s voting. A critical piece was getting women to register to vote. Because women could already vote for their school committee in Massachusetts, they could be enrolled as voters in advance of ratification. (For more information about female school committee voting, see our blog post.) When aspiring voters met with the board of registrars in their voting district, they had to show that they were citizens, at least 21, and able to read and write English and that they had lived at least one year in Massachusetts and six months in their voting district. They were also expected to answer questions about parentage and nationality and to prove naturalization if necessary. (Aug. 18, p. 4) The first election in which they could fully participate was a primary in September 1920. As pointed out in the Maynard column of the August 11 Enterprise, “With no district contests among the Democrats there is very little interest shown.” The Maynard Republican Women’s committee, on the other hand, announced a number of reasons for registering, including participating in a great historical event, honoring the 70 years in which “some of the ablest women of America gave their lives to the winning of this right for women”, and helping to “elect men who will look out for the children’s welfare” and “secure good working conditions for you.” (Electing women was obviously an issue for another day.) If those weren’t good enough reasons, women should register because they didn’t “want it said that the women of Massachusetts were behind the women of other States in meeting the responsibilities of citizenship.” (Aug. 11, p. 1) In Acton, registration was a success. On Sept. 8, the Enterprise reported that in South Acton, forty-nine women (and nine men) registered (p. 1), while in West Acton, “At the meeting of the board of registrars Thursday night, the number broke all records, when 80 women were recorded and 14 men were added to the list.” (p. 5) Acton Centre reported “quite a number” had registered for the primary and more were expected for the November election. (Sept. 22, p. 5) Though fanfare about the first election was fairly minimal in the paper, the West Acton reporter noted on September 15, “The women of Precinct 3 are to be congratulated on their good work at the primaries last week, when they cast their first votes. Mrs. Albert R. Beach cast the first ladies’ vote here.” (p. 6) Getting women onto the voter rolls was not enough. Women had to overcome people’s lack of faith in their abilities, judgment, and knowledge. One way to combat low expectations was through education. In Maynard, the Women’s Club sponsored a series of ten classes on government and the duties of citizenship. (Sept.8, p. 4) In Acton, there was so much concern about women’s ability to handle the physical act of voting that lectures were held to help: “A citizens’ meeting will be held in the vestry of the Universalist church on Thursday evening, Oct. 21, at 7:30 o’clock under the auspices of the Republican town committee. Miss Grace Carruth of Boston has been engaged speaker and will address the meeting upon the subject ‘How to Mark the Ballot’ and will be prepared to answer any other questions of present political interest. Similar meetings will be held during the afternoon of the same day at Acton and West Acton. All persons interested are invited to attend.” (Oct. 20, 1920, p. 1) The Acton Woman’s Club, a little behind, scheduled a speaker on Nov. 22 to help its members “in the study of simple non-partisan citizenship.” (Nov. 10, p. 8) Election day came on November 2. The first women voters in South Acton that day were Grace and Lyde Fletcher who had come back from Watertown the previous evening to be able to cast their ballots. (Nov. 11, p. 8) Another female voter in South Acton was Mary H. Lothrop who, with her husband Frank on the way to Florida, “took advantage of the privilege of absent voters and sent their depositions by mail.” (Nov. 10, p. 1) The vote was especially memorable for South Acton’s Carrie Franklin. Of obvious importance, she was able to participate in a historic moment, voting with her husband William in a national election. The surprise was that during the 45 minutes it took to cast their ballots and return, their home was burgled. Money and Mrs. Franklin’s jewelry were stolen. The perpetrators had apparently watched them leave the house. It turned out to be three boys from Maynard, later found by the railroad tracks with Mrs. Franklin’s watch. Overall, when the Enterprise reported on the election of 1920, it had to note that the women of Acton had managed to vote without disaster. In South Acton, “Out of a total of 313 registered votes, 278 votes were cast, or about 89 per cent, which is probably the largest proportionate votes ever cast here. The counting was completed and returns complete at 6:30 p. m. The women manifested great interest and marked their ballots with ease and rapidity.” (Nov. 3, p. 4) In West Acton, the report was, “No Ballots Thrown Out – With 347 voters in Precinct 3 there were 322 votes cast on election day. Not one ballot was marked wrong which is a fine showing with so many new voters and a great credit to the ladies.” (Nov. 10, 1920, p. 2) The landslide victory of Harding and Coolidge over Democrats Cox and Roosevelt rated huge front-page headlines from the Enterprise on November 3, 1920. In the following weeks, the paper mentioned more civics lectures sponsored by women’s clubs and organizational details about the League of Women Voters and the Women’s Auxiliary of the Foreign Legion. In Maynard, there was talk of running a woman for the school board and forming a Parent-Teachers’ association. There was obviously plenty of work needed to achieve the goals of improving living conditions, fostering equality, and protecting children; they would not happen magically because women could vote. When the Nineteenth Amendment officially became law on August 26, 1920, it was a milestone that was achieved after decades of struggle. Its importance should not be underestimated. At the same time, it has to be recognized that suffrage was not universal, given restrictions on who was considered a citizen and who was allowed to be registered to vote. The work did not end that day. --------------------------------- *All newspaper references here are to issues of the Concord Enterprise that at the time covered Concord, Concord Junction, the four Acton villages, Maynard, Sudbury and sometimes Bedford and Marlborough. Sometimes a seemingly identical paper was published as the Acton Enterprise. 7/24/2020 Acton's Early Black ResidentsGaining an understanding of a town’s history is complicated by the fact that some residents’ stories are much less accessible than others. Standard town histories from the nineteenth and early twentieth century tended to focus on a small group of socially prominent citizens. People of color were seldom mentioned. Anyone trying to learn about the early Black residents of Acton has had very little material to work with. Records are sparse, and there are sometimes conflicts among the pieces of information that we do have. To better understand early Acton’s racial diversity, we set out to find all mentions of Black and mixed-race residents (slave or free) in Acton’s early records. To do that, we used eighteenth- and nineteenth-century documents that sometimes refer to racial diversity with terms that we would not use today. When quoted here, it is only to give accurate historical evidence about a person’s racial background. There is much work left to do, but in collaboration with the Robbins House in Concord, we offer what we have learned so far. We will start in 1735 when Acton was set off as a town from Concord. We are hampered by lack of census records in the early days but will continue to look for more information. We do have a definitive record that slavery existed in Acton after it became a town. The 1754 Massachusetts slave census completed by the Selectmen stated that there was “but one male Negro slave Sixteen years old in Acton and No females.” (The inventory asked for the number of slaves over the age of sixteen; the wording presumably meant that the male mentioned was in that category, rather than being exactly sixteen years old.) We have no way of knowing if there were any younger slaves. Unfortunately, the inventory did not list either the name of the slave or the slave owner. As a result, we have no idea whether he was eventually freed and whether he stayed in town or moved on to another location. Acton apparently also had free Black and/or mixed-race residents during its earliest years. We are still trying to document their stories. In South Acton by 1731, there was a William Cutting who, according to a story in a published journal of Rev. William Bentley, (volume 2, page 148) was himself or descended from a “Mulatto” slave who “upon the death of his master, accepted some wild land, which he cultivated & upon which his descendants live in independence.” (This story is still being researched; our various efforts to confirm those details have not yet been successful. A 1731 deed from Elnathan Jones to William Cutting is extremely hard to read, but it mentions a purchase price paid to a living person, rather than a gift or inheritance. Another 1732 deed from Elnathan Jones also seems to be a straight sale. Probate records have not yielded clues, either. A possibility is that the story was about an earlier ancestor in a location other than Acton.) An Acton’s Selectmen’s report dated Feb. 2, 1753 mentions a road being laid out, with one of the boundaries being “a Grey oke on Ceser Freemans Land.” Both Cesar and Freeman were names associated with free African Americans of the period. Cesar Freeman’s story is unknown at this point, so we do not know if other Freemans in town records are his relatives. Harvard University has put online a transcribed and indexed version of the Massachusetts Tax Inventory of 1771. This inventory reported the number of each taxpayer’s “servants for life.” According to that database, there were two “servants for life” in Acton, assessed to Amos Prescott and Simon Tuttle. (For relevant entries click here.) We know nothing about the person assessed to Prescott. However, it appears that Simon Tuttle’s “man” fought in the Revolution. At town meeting on March 4, 1783, the town voted to reimburse Mr. Simon Tuttle for “the Bounty for his negro man which was Twenty four Pounds in March 1777 to be Paid by the Scale of Depreciation.” Simon Tuttle was one of the Acton leaders who was charged with recruiting men to enlist from Acton, and it was common practice for the recruiters to pay bounties for enlistment out of their own pockets on the understanding that they would be reimbursed. (Acton took such a long time about actually paying the men back that the value of currency completely changed and adjustments needed to be made “by the Scale of Depreciation.”) The unique thing about this 1783 entry in town records is that the recruit was described at all, in particular his race and the fact that he was considered Simon Tuttle’s man. We have a clue as to his name; Rev. Woodbury's list of known Revolutionary War soldiers from Acton (compiled in the mid-1800s) included the entry "Titus Hayward, colored man, hired by Simon Tuttle." For more information about this soldier, see our blog post about our research into his identity. Acton did have a free Black population in the years of and following the Revolution. John Oliver, listed in later census records (inconsistently) as a free person of color, enlisted for Revolutionary war service from Acton as early as April 1775. John Oliver lived in North Acton in an area near the town’s borders with Westford and Littleton. We are investigating whether there was a community of Black and mixed-race residents in that area. What we know about John’s life in particular was discussed in a previous blog post, and the location of his farm was discussed in another. Another Black Revolutionary War soldier with Acton ties was Caesar Thomson who appeared in Acton’s records after the war. According to an article published by the Historical, Natural History and Library Society of South Natick in 1884 (page 100), Cesar Thompson was a slave of Samuel Welles, Jr., a Boston merchant and the largest landowner in Natick by the time of the Revolution. When Natick needed men to fill its quota of soldiers, Mr. Welles sent Cesar, whose Revolutionary War service was extensive. (See Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War, Volume 15, pages 631 and 668). After serving for several years, he was “disabled by a rupture” and was actually granted a pension in January 1783. (Pensions were granted to disabled soldiers, though full pension coverage for veterans was far in the future. Unfortunately, the earliest Revolutionary War pension records were lost in a fire.) As stated in the 1884 article, Natick town records contain the following notation: “Boston, Feb. 18, 1783. This may certify, to all whom it may concern, that I this day, fully and freely give to Caesar Thompson his freedom. Witness my hand, Samuel Welles. A true copy. Attest, Abijah Stratton, Town Clerk.” After the war, free man Cesar Thompson lived in Acton. At the April 5, 1783 town meeting, a committee was appointed to figure out seating for the meeting house (a regular occurrence). Seating arrangements were to take into consideration age and property, using the prior two years’ tax valuations. It was voted that the committee was to “Seat the negros in the hind Seats in the Side gallery.” Clearly, despite years of fighting for political freedom and equality of “all people,” Acton was not ready to grant equality to all of its own people. (It should be noted that it was an era in which citizens paid for pews in the meetinghouse, which was not only a church, but the place were town meetings took place. Presumably, pew placement denoted social status.) In an 1835 centennial speech, Josiah Adams recounted a childhood memory that reveals how it must have felt to be one of very few people of color in the town at the time. Young Adams would watch as Quartus Hosmer climbed the stairs to the “hind seat” of the gallery, eagerly waiting for him to reappear with his queue of “graceful curls” held back by an eel-skin ribbon. (Adams, Josiah. An address delivered at Acton, July 21, 1835: being the first centennial anniversary of the organization of the town, Boston: Printed by J. T. Buckingham, 1835, page 6)

It cannot have been comfortable to be a curiosity to young Actonians and to deal with attitudes made obvious by the meeting house seating vote. Nevertheless, some residents of African descent stayed in Acton. John Oliver farmed and raised his family with his wife Abigail Richardson. (Their known children were Abijah, Joel, Fatima and Abigail. We suspect, but have not yet been able to confirm, that there were others.) Cesar Tomson/Thompson was mentioned in town records when, on January 27, 1785, he married Azubah Hendrick (both were of Acton), Azubah was admitted to the church, and their children were baptized (Joseph, Moses and Dorcas). There is no record of what happened to Azubah, but Caesar married Peggy Green in Acton on December 1, 1785. He also appeared in town records on Feb. 23, 1789 when his tax rate was abated. While researching the Thompson family, we discovered that other Massachusetts towns’ vital records might hold clues about Acton’s Black residents. In Natick, we found two birth records (on the page before the 1801 intention of marriage for Dorcas Tomson, then living in that town): “Moses Hendrick son of Benjamin and Zibiah Hendrick was Born in Acton September 15. 1780 Dorcas Tomson Daughter of Ceasar and Zibiah Tomson was born in Acton April 1. 1784” In Grafton, we found a marriage intention between Polly Johns and “Moses Hendrick, ‘a native he says of Acton but now resident of Grafton,’ int[ention] Aug. 30, 1817. Colored.” Until we found these two records, we had no idea that a Black man named Moses Hendrick had been born in town. Another discovery was that at town meeting in August 1786, the town discussed suing Peter Oliver and Philip Boston “for Refusing to maintain Lucy W___ [name extremely uncertain, some think Willard] Child agreeable to their obligation.” Though both names were associated with free people of color in nearby towns, we have not figured out exactly who these men were or what their connection was to Lucy Willard. On March 19, 1792, the town paid Simon Tuttle Jr. for assistance given to Peter Oliver. The first full census of the United States came in 1790. Though only the heads of household were named, it gives us a more complete picture of the composition of the households in Acton. The census asked for the numbers of free white males (16 or older and under 16), free white females, slaves, and “all other free persons.” Acton had no slaves in this or later censuses. The census taker seems to have had some issues with accounting for “other free persons,” and the census scan is in places hard to read, but from what we can see, the following households had free persons of color:

The census shows six total free persons of color out of the 853 people in 1790 Acton. The seven people in John Oliver’s household were classified as white (2 males, 5 females), as were the nine members of William Cutting Jr.’s household (3 males, 6 females). In the beginning of the 1790s, Acton worked to specify those who were not considered legal residents, a step toward defining its responsibility toward the poor. The Revolutionary War had caused economic distress for many people in the new country. There were no safety nets as we understand them today. Then as now, towns were reluctant to tax people for any expenses that could be avoided. Under the system that had been in place since the early days of the colony, towns could avoid responsibility for supporting poor people if they were not considered legal residents of the town. Formally, this meant giving people notice that they had not been granted permission to live in town and that they should leave (and therefore that they had no right to expect help from the town if they stayed). This process was called “warning out.” From about 1767 to 1789, warning out seemed to be dying out in Massachusetts. However, a law change in 1789 led to a flurry of warnings out in Acton and elsewhere. In the 1790-1791 period, town records show that 23 households were warned out of Acton. Included were a number of Revolutionary War veterans and long-time inhabitants. John Oliver and Cesar Thomson, their wives, and their children were on the list. Both families stayed in town, as most warned-out people probably did in the 1790s. As a practical matter, if those people become indigent, assistance would still have been given them, but the town, relieved of its legal responsibility, could petition the state for reimbursement. Available in Harvard’s Anitslavery Petitions Massachusetts Dataverse is a July 1, 1796 petition from Jonas Brooks to the Commonwealth to reimburse the inhabitants of Acton for “considerable expense in supporting Caesar Thompson a negro man, together with his wife, three small children” who were “not legally settled in said Town of Acton or in any other town in said Commonwealth that your petitioner can find - That he served as a soldier in the Continental army during the last war...” The town sent a follow-up petition for state reimbursement in 1797. As a former slave, Cesar apparently had no legal claim on Natick (despite filling its quota in the Revolutionary War) or Boston, where he might have lived before serving in the military. After the petitions, we found no more records for Caesar Thompson; whether he died in Acton or moved, we were not able to determine. We do know that his daughter had moved to Natick by 1801. The 1800 census asked for more information than its predecessor. Only the heads of Acton households were listed, but the ages of white inhabitants were broken out more carefully. Acton’s census return had a column for the number of slaves and one for “All other persons except Indians not taxed.” With entries in that somewhat perplexingly-named column were the households of:

William Cutting Jr.’s household of seven was again listed as white. Also of note in the 1800 census is that many of the warned-out families were still in town. Acton’s vital records show that in December 1802, Sally Oliver married Jacob Freeman. Their relationship to people of the same surnames in town is unclear (so far). Sadly, Sally and Jacob had only a short marriage marked by tragedy. Their son died on Sept. 3, 1803. Jacob died on July 9, 1804 at age 45. Acton’s death record specifies his race as negro. (In early 1805, Amos Noyes, Joseph Brabrook, and Edward Weatherbee were paid for goods delivered to Jacob, presumably during his sickness.) 1810’s Acton census had a column for “All free other persons, except Indians, not taxed.” Acton households with someone in that category were:

John Oliver’s sons’ 1810 households were classified as white. The household of Abijah Oliver had 1 male 45+, 3 females <10 and 1 female 16-25. Joel Oliver’s household had 1 male <10, 1 male 26-44, 2 females 10-15, and 1 female 26-44. William Cutting Jr. was also classified as white. During the 1810s, town records show payments for some Black residents in need. Between 1813 and 1815, John Oliver was providing help to others, including Abijah Oliver and, when sick, “Abigal” Oliver and Sally (Oliver) Freeman. In 1811-15, John Robbins and David Barnard were reimbursed for boarding “Titus Anthony.” Later records give clues that he may have been Black (see below). (Probably relatedly, in March 1810, town meeting records mention a lawsuit by the town of Townsend against Acton “for supporting Hittey Anthony and Child.”) Acton town meeting took up Titus Anthony’s case in September 1811; unfortunately, the discussion was not reported in the extant records. In 1813, David Barnard was paid for providing for the poor and, separately, for “2 payment for the Negro” (name unspecified). 1820’s census yields more information about Black town residents. In that year’s report, “Free colored Persons” had four columns each for males and females of differing ages. Households with entries in those columns were:

1820’s total “free colored” population was listed as 17, which does not match the numbers given in the columns, so the accounting is uncertain. John Oliver’s 2-person household was listed as white. Regardless of the counting issues, there was obviously quite a community of people of color in Acton during the 1820s. Most lived in the North and East parts of town. The households of Jonathan Davis and Uriah Foster would have been near today’s Route 27 in North Acton. John Oliver’s sons Abijah and Joel eventually moved closer to East Acton; land records indicate that their father helped with financing. In 1830, federal census takers were given forms two page-widths across that specified ages and sex of both slaves and free people of color and had a “total” column for each family that should have encouraged accurate record-taking. The only household in which free persons of color were enumerated was John Oliver’s:

John’s son Joel Oliver was listed as white, living with 5 white females. Simon Hosmer’s family no longer was listed with a free person of color. This jibes with the hypothesis that the “Quartus Hosmer” mentioned by Josiah Adams lived in the Jonathan/Simon Hosmer household. In Acton’s vital records, the handwritten register of Acton deaths for 1827 shows: “June 30 Quartus a Blackman 61” The Hosmer name was not given in the death record. (This entry was indexed on Ancestry.com as “Quartus Blackman,” but that is clearly an error.) In Acton’s transcribed and published Vital Records to 1850, the listing appeared under “Negroes, Etc.” That entry adds information from church records (“C. R. I.”): “Quartus, ‘a Black man,’ June 30, 1827, a. 61 [State pauper, a. 64, C. R. I.] A state pauper meant that the individual had no “settlement” status. (Acton could not send him or her back to another Massachusetts town for financial support, but he/she was not officially accepted as having a claim on Acton either.) By this time, if a person with no official claim on a town was in need based on age, disability, illness or poverty, he/she became, officially, a state pauper, and expenses incurred by the town would be billed to the state. Apparently, former slaves often found themselves in this position (Cesar Thompson, for example), as well as new immigrants from overseas and anyone not connected to a town by family or marriage. Quartus’ status as a state pauper means either that he was free but didn’t start off in Acton or that he had started out a slave. If we are correct that the free person of color in the Hosmer household was this Quartus, he clearly had a long relationship with the family. The available records do not give us much information about what the relationship was, but we have not found evidence that he had been enslaved by Acton Hosmers. This Quartus was too young to have been the over-16-year-old slave in the 1754 census, though slaves younger than sixteen were not reported. The 1771 tax valuation showed no Acton Hosmers with “servants for life.” He could have been freed by then or could have been enslaved elsewhere in his early years and later entered the Hosmer household as a free working person. The 1840 census showed “free colored persons” in the households of:

The census shows the household of John Oliver, especially noted for being 92 years of age and a military pensioner, as white (1 male under 5, 1 male 5-9, 1 male 90-99, 1 female 5-9, 1 female 40-49). His son Joel Oliver’s household is also listed as white, (2 males, 30-39 and 60-69, and 2 females, 15-19 and 50-59). During the 1840s, many in Acton were advocating for an end to slavery in general and for improvements in laws affecting the lives of Massachusetts’ Black residents. A digitized 1842 petition from Acton to allow white people legally to intermarry with other races was signed by 70 women, including Abigail Chaffin who was most likely Abigail Richardson (Oliver) Chaffin, herself of mixed-race ancestry. (Abijah Oliver’s daughter, she had married Nathan Chaffin, born in Acton to Nathan and Mary Chaffin. After that point, records always seem to have classified her as white.) Abigail Chaffin also signed two other anti-slavery petitions in 1842 ( Petition against admission of Florida as Slave State and Petition to abolish slavery in Washington, DC and territories and to end the slave trade). Abigail Chaffin was remembered in a Chaffin family history (pages 269-270) as “one of the most remarkable women ever born in Acton, on account of the wonderful sagacity, industry and executive ability, which characterized her through the whole of her life and... together with mental and physical vigor, to a very rare age. ... Even after she was four score and ten she was able to do more for others than she needed to have done for herself.” After the death of her husband in 1878, she moved in with her son Nathan who prospered in the restaurant business in Boston. She lived in Arlington for many years, and she died in Bedford in 1911, after having “passed her last years not only in the possession of the comforts, but of the luxuries of life.” Back in Acton, the 1850 census, for the first time, listed the names of all residents of the town. A column for race showed the following residents of color:

The race column for all other residents was left blank (including the 7-person household of Joel Oliver, Abijah’s brother). The 1850 real estate valuation for the town shows Ephraim Oliver (son of Joel) with buildings valued $375, plus 40 acres of improved land and 20 acres of unimproved land; he was living with Joel at the time. Abijah Oliver had been farming in East Acton, but obviously he was no longer able to care for himself. It was not particularly unusual for the aged, regardless of race, to need assistance. Massachusetts took its own census in 1855. We have noticed in the past that the Acton census taker that year was particularly careful in recording full names, and the census taker noted more information about race as well:

We have not yet been able to find out where Titus Anthony Williams came from and how he ended up in Acton’s poor house. The middle name reported in the 1855 census raises the question of whether the “Titus Anthony” who was receiving assistance in the 1810s was actually the same Titus Anthony Williams who spent many years in Acton’s poor house (occupation farmer). If so, he would have been a young child when he first appeared in Acton’s records. By the mid-1800s, Acton was changing. The arrival of the railroad brought new industry and new people to town, and events in Europe brought new immigrants who would have competed for jobs and land. Most descendants of Acton’s early Black residents eventually left Acton to find opportunities elsewhere. Occasionally, they were mentioned in later records. Sickness, disability, loss of a breadwinner, or extreme old age could change economic status. Acton’s town report of 1855-1856 shows payment to the city of Boston for the support of Elizabeth Oliver (probably the recent widow of Abijah Oliver), and to the town of Concord for the burial of two of Peter Robbin’s family, as well as to Daniel Wetherbee of Acton for goods provided to that family. (Peter Robbins had recently died. He was divorced from John Oliver’s daughter Fatima by that time; apparently, his common law wife Almira/Elmira came from Acton, though her parentage is currently unclear. She is referred to in Acton’s records as Elmira Oliver.) The 1857-58 report shows money paid to Lowell for the support of Sarah Jane (Tucker) Oliver. (She apparently married William P. Oliver and then Asa Oliver; their connections to other Acton Olivers are still being worked out). Others receiving help that year who were not living at the poor farm included Sarah Spaulding (John Oliver’s widowed granddaughter) and Elizabeth Oliver. The 1860 Federal Census showed the following:

The 1860 census also surveyed the town’s agriculture and gave details about Ephraim Oliver’s farming operation, located at approximately 283 Great Road in East Acton. Ephraim Oliver owned 43 improved and 10 unimproved acres worth $3,000, plus $100 in farming implements, a horse, four milking cows, and fifteen other cattle. His farm produced 140 bushels of “Indian corn,” 15 bushels of oats, 40 bushels of “Irish potatoes,” 200 pounds of butter, 10 tons of hay and 5 bushels of grain seed. Though she was not listed in the poor house in the census, Sarah (Olivers) Spaulding was listed in Acton’s 1860 death records as a pauper. She died, widowed, at age 36 on Oct. 14, 1860 and was listed as a quadroon, daughter of Abijah and Rachel (Barber) Oliver. (Abijah was married to Elizabeth Barber, so that is probably simply an error.) The final census in this survey is the Massachusetts census of 1865. By that time, Civil War and emancipation had set enormous changes in motion. The census reported the following people of color in Acton:

All other residents were classified as white, including the five-person household of Ephraim Oliver. We still have many questions that need answers. In the relatively helpful records of the 1860s, we found other mentions of Olivers with connections to Acton that we have not yet been able to untangle: